Ann Lab Med.

2024 Nov;44(6):537-544. 10.3343/alm.2024.0025.

Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Pharyngeal Gonorrhea in Korean Men With Urethritis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, National Health Insurance Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Gangneung Asan Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Gangneung, Korea

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine and Research Institute of Bacterial Resistance, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Lee Sangbong Urologic Clinic, Wonju, Korea; 5 Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea

- 5Seoul Clinical Laboratories Academy, Yongin, Korea

- KMID: 2560800

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3343/alm.2024.0025

Abstract

- Background

Pharyngeal infection is more difficult to diagnose and treat than genital or rectal infection and can act as a reservoir for gonococcal infection. We determined the prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in Korean men with urethritis and analyzed the molecular characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolates.

Methods

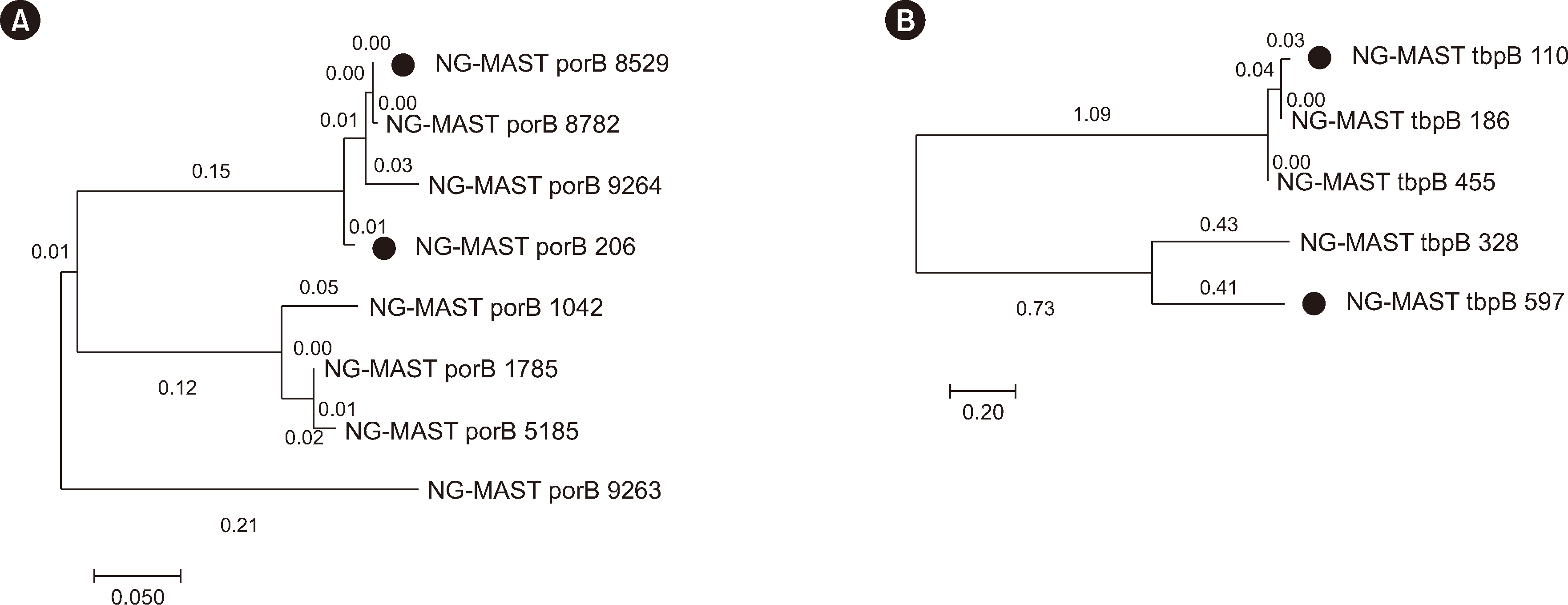

Seventy-two male patients with symptoms of urethritis who visited a urology clinic in Wonju, Korea, between September 2016 and March 2018 were included. Urethral and pharyngeal gonococcal cultures, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, Neisseria gonorrhoeae multi-antigen sequence typing (NG-MAST), and multiplex real-time PCR (mRT-PCR) were performed.

Results

Among the 72 patients, 59 tested positive for gonococcus by mRT-PCR. Of these 59 patients, 18 (30.5%) tested positive in both the pharynx and urethra, whereas 41 tested positive only in the urethra. NG-MAST was feasible in 16 out of 18 patients and revealed that 14 patients had the same sequence types in both urethral and pharyngeal specimens, whereas two patients exhibited different sequence types between the urethra and pharynx. Of the 72 patients, 33 tested culture-positive. All patients tested positive only in urethral specimens, except for one patient who tested positive in both. All culture-positive specimens also tested positive by mRT-PCR. All isolates were susceptible to azithromycin and spectinomycin, but resistance rates to ceftriaxone and cefixime were 2.9% and 14.7%, respectively.

Conclusions

The prevalence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in Korean men with gonococcal urethritis is as high as 30.5%, highlighting the need for pharyngeal screening in high-risk groups. Ceftriaxone is the recommended treatment for pharyngeal gonorrhea.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. WHO. 2021. Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021. Geneva: Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077. Updated on May 2024.2. Unemo M, Golparian D, Eyre DW. 2019; Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and treatment of gonorrhea. Methods Mol Biol. 1997:37–58. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9496-0_3. PMID: 31119616.3. Bleich AT, Sheffield JS, Wendel GD Jr., Sigman A, Cunningham FG. 2012; Disseminated gonococcal infection in women. Obstet Gynecol. 119:597–602. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318244eda9. PMID: 22353959.4. Fairley CK, Hocking JS, Zhang L, Chow EP. 2017; Frequent transmission of gonorrhea in men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis. 23:102–4. DOI: 10.3201/eid2301.161205. PMID: 27983487. PMCID: PMC5176237. PMID: 9053814eef8c43b481d30983cc68c4d3.5. Chow EP, Tabrizi SN, Phillips S, Lee D, Bradshaw CS, Chen MY, et al. 2016; Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterial DNA load in the pharynges and saliva of men who have sex with men. J Clin Microbiol. 54:2485–90. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01186-16. PMID: 27413195. PMCID: PMC5035428.6. Lewis DA. 2015; Will targeting oropharyngeal gonorrhoea delay the further emergence of drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains? Sex Transm Infect. 91:234–7. DOI: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051731. PMID: 25911525.7. Giannini CM, Kim HK, Mortensen J, Mortensen J, Marsolo K, Huppert J. 2010; Culture of non-genital sites increases the detection of gonorrhea in women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 23:246–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.003. PMID: 20434928.8. Jenkins WD, Nessa LL, Clark T. 2014; Cross-sectional study of pharyngeal and genital chlamydia and gonorrhoea infections in emergency department patients. Sex Transm Infect. 90:246–9. DOI: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051358. PMID: 24366777.9. Wada K, Uehara S, Mitsuhata R, Kariyama R, Nose H, Sako S, et al. 2012; Prevalence of pharyngeal Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae among heterosexual men in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 18:729–33. DOI: 10.1007/s10156-012-0410-y. PMID: 22491994.10. Callander D, McManus H, Guy R, Hellard M, O'Connor CC, Fairley CK, et al. 2018; Rising chlamydia and gonorrhoea incidence and associated risk factors among female sex workers in Australia: a retrospective cohort study. Sex Transm Dis. 45:199–206. DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000714. PMID: 29420449.11. Martin IM, Ison CA, Aanensen DM, Fenton KA, Spratt BG. 2004; Rapid sequence-based identification of gonococcal transmission clusters in a large metropolitan area. J Infect Dis. 189:1497–505. DOI: 10.1086/383047. PMID: 15073688.12. Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016; MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 33:1870–4. DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. PMID: 27004904. PMCID: PMC8210823.13. CLSI. 2023. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 33rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;Wayne, PA: CLSI M100. DOI: 10.1016/s0196-4399(01)88009-0.14. Newman LM, Moran JS, Workowski KA. 2007; Update on the management of gonorrhea in adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 44(S3):S84–101. DOI: 10.1086/511422. PMID: 17342672.15. Shim BS. 2011; Current concepts in bacterial sexually transmitted diseases. Korean J Urol. 52:589–97. DOI: 10.4111/kju.2011.52.9.589. PMID: 22025952. PMCID: PMC3198230.16. Javanbakht M, Westmoreland D, Gorbach P. 2018; Factors associated with pharyngeal gonorrhea in young people: implications for prevention. Sex Transm Dis. 45:588–93. DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000822. PMID: 29485543. PMCID: PMC6086760.17. Chan PA, Robinette A, Montgomery M, Almonte A, Cu-Uvin S, Lonks JR, et al. 2016; Extragenital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a review of the literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2016:5758387. DOI: 10.1155/2016/5758387. PMID: 27366021. PMCID: PMC4913006. PMID: 0b0d82fcb18b442297b000d1fdbcb9df.18. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Medical statistics information. https://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olap4thDsInfoTab1.do. Updated on May 2024.19. Cornelisse VJ, Chow EP, Huffam S, Fairley CK, Bissessor M, De Petra V, et al. 2017; Increased detection of pharyngeal and rectal gonorrhea in men who have sex with men after transition from culture to nucleic acid amplification testing. Sex Transm Dis. 44:114–7. DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000553. PMID: 27984552.20. Oree G, Naicker M, Maise HC, Tinarwo P, Ramsuran V, Abbai NS. 2021; Comparison of methods for the detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from South African women attending antenatal care. Int J STD AIDS. 32:396–402. DOI: 10.1177/0956462420971439. PMID: 33570465.21. Hananta IPY, De Vries HJC, van Dam AP, van Rooijen MS, Soebono H, Schim van der Loeff MF. 2017; Persistence after treatment of pharyngeal gonococcal infections in patients of the STI clinic, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2012-2015: a retrospective cohort study. Sex Transm Infect. 93:467–71. DOI: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053147. PMID: 28822976. PMCID: PMC5739854.22. Kong FYS, Hocking JS. 2022; Treating pharyngeal gonorrhoea continues to remain a challenge. Lancet Infect Dis. 22:573–4. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00649-6. PMID: 35065062.23. Lee H, Lee K, Chong Y. 2016; New treatment options for infections caused by increasingly antimicrobial-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 14:243–56. DOI: 10.1586/14787210.2016.1134315. PMID: 26690658.24. Moran JS. 1995; Treating uncomplicated Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections: is the anatomic site of infection important? Sex Transm Dis. 22:39–47. DOI: 10.1097/00007435-199501000-00007. PMID: 7709324.25. Unemo M, Golparian D, Potočnik M, Jeverica S. 2012; Treatment failure of pharyngeal gonorrhoea with internationally recommended first-line ceftriaxone verified in Slovenia, September 2011. Euro Surveill. 17:DOI: 10.2807/ese.17.25.20200-en. PMID: 22748003.26. Tapsall J, Read P, Carmody C, Bourne C, Ray S, Limnios A, et al. 2009; Two cases of failed ceftriaxone treatment in pharyngeal gonorrhoea verified by molecular microbiological methods. J Med Microbiol. 58:683–7. DOI: 10.1099/jmm.0.007641-0. PMID: 19369534.27. Ito S, Hanaoka N, Shimuta K, Seike K, Tsuchiya T, Yasuda M, et al. 2016; Male non-gonococcal urethritis: from microbiological etiologies to demographic and clinical features. Int J Urol. 23:325–31. DOI: 10.1111/iju.13044. PMID: 26845624.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Study of Pharyngeal Gonorrhea

- Treatment of Uncomplicated Male Gonococcal Urethritis with Ofloxacin

- Treatment of Uncomplicated Male Gonococcal Urethritis with Rosoxacin

- Epidemiological Treatment for Postgonococcal Urethritis in Uncomplicated Male Gonococcal Urethritis

- Clinical Aspects of Gonorrhea: V. Double dose of sodium penicillin G. in the treatment of male gonorrhea