Korean Circ J.

2024 Jun;54(6):325-335. 10.4070/kcj.2023.0300.

Impacts of Pre-transplant Panel-Reactive Antibody on Post-transplantation Outcomes: A Study of Nationwide Heart Transplant Registry Data

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Thoracic Surgery, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 7Department of Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Department of Internal Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2556530

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2023.0300

Abstract

- Background and Objectives

The number of sensitized heart failure patients on waiting lists for heart transplantation (HTx) is increasing. Using the Korean Organ Transplantation Registry (KOTRY), a nationwide multicenter database, we investigated the prevalence and clinical impact of calculated panel-reactive antibody (cPRA) in patients undergoing HTx.

Methods

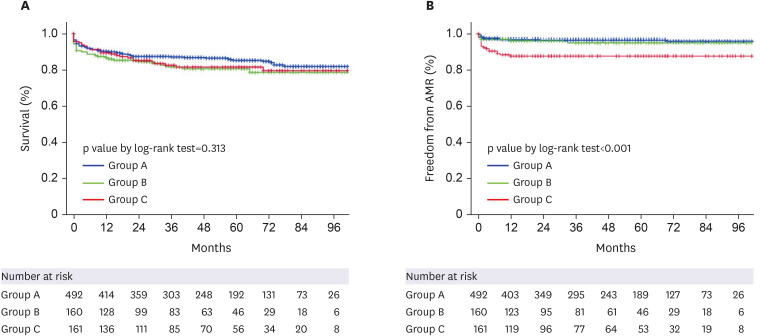

We retrospectively reviewed 813 patients who underwent HTx between 2014 and 2021. Patients were grouped according to peak PRA level as group A: patients with cPRA ≤10% (n= 492); group B: patients with cPRA >10%, <50% (n=160); group C patients with cPRA ≥50% (n=161). Post-HTx outcomes were freedom from antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), acute cellular rejection, coronary allograft vasculopathy, and all-cause mortality.

Results

The median follow-up duration was 44 (19–72) months. Female sex, retransplantation, and pre-HTx renal replacement therapy were independently associated with an increased risk of sensitization (cPRA ≥50%). Group C patients were more likely to have longer hospital stays and to use anti-thymocyte globulin as an induction agent compared to groups A and B. Significantly more patients in group C had positive flow cytometric crossmatch and had a higher incidence of preformed donor-specific antibody (DSA) compared to groups A and B. During follow-up, group C had a significantly higher rate of AMR, but the overall survival rate was comparable to that of groups A and B. In a subgroup analysis of group C, post-transplant survival was comparable despite higher preformed DSA in a desensitized group compared to the non-desensitized group.

Conclusions

Patients with cPRA ≥50% had significantly higher incidence of preformed DSA and lower freedom from AMR, but post-HTx survival rates were similar to those with cPRA <50%. Our findings suggest that sensitized patients can attain comparable post-transplant survival to non-sensitized patients when treated with optimal desensitization treatment and therapeutic intervention.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Mehra MR, Uber PA, Uber WE, Scott RL, Park MH. Allosensitization in heart transplantation: implications and management strategies. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2003; 18:153–158. PMID: 12652223.2. Urban M, Gazdic T, Slimackova E, et al. Alloimmunosensitization in left ventricular assist device recipients and impact on posttransplantation outcome. ASAIO J. 2012; 58:554–561. PMID: 23069898.3. Kim SE, Yoo BS. Treatment Strategies of Improving Quality of Care in Patients With Heart Failure. Korean Circ J. 2023; 53:294–312. PMID: 37161744.4. Hsich E, Singh TP, Cherikh WS, et al. The International thoracic organ transplant registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirty-ninth adult heart transplantation report-2022; focus on transplant for restrictive heart disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022; 41:1366–1375. PMID: 36031520.5. Nwakanma LU, Williams JA, Weiss ES, Russell SD, Baumgartner WA, Conte JV. Influence of pretransplant panel-reactive antibody on outcomes in 8,160 heart transplant recipients in recent era. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007; 84:1556–1562. PMID: 17954062.6. Kim D, Choi JO, Oh J, et al. The Korean Organ Transplant Registry (KOTRY): second official adult heart transplant report. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:724–737. PMID: 31074219.7. Zachary AA, Ratner LE, Graziani JA, Lucas DP, Delaney NL, Leffell MS. Characterization of HLA class I specific antibodies by ELISA using solubilized antigen targets: II. Clinical relevance. Hum Immunol. 2001; 62:236–246. PMID: 11250041.8. Chang DH, Youn JC, Dilibero D, Patel JK, Kobashigawa JA. Heart transplant immunosuppression strategies at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Int J Heart Fail. 2020; 3:15–30. PMID: 36263111.9. Youn JC, Kim D, Cho JY, et al. Korean Society of Heart Failure guidelines for the management of heart failure: treatment. Korean Circ J. 2023; 53:217–238. PMID: 37161681.10. Berry GJ, Burke MM, Andersen C, et al. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Working Formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the pathologic diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013; 32:1147–1162. PMID: 24263017.11. Fisher B, Anderson S, Fisher ER, et al. Significance of ipsilateral breast tumour recurrence after lumpectomy. Lancet. 1991; 338:327–331. PMID: 1677695.12. Gopal AK, Press OW. Clinical applications of anti-CD20 antibodies. J Lab Clin Med. 1999; 134:445–450. PMID: 10560936.13. Kobashigawa JA, Patel JK, Kittleson MM, et al. The long-term outcome of treated sensitized patients who undergo heart transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2011; 25:E61–E67. PMID: 20973825.14. Colvin MM, Cook JL, Chang PP, et al. Sensitization in heart transplantation: emerging knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019; 139:e553–e578. PMID: 30776902.15. Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2018; 18(Suppl 1):18–113. PMID: 29292608.16. Alachkar N, Lonze BE, Zachary AA, et al. Infusion of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin fails to lower the strength of human leukocyte antigen antibodies in highly sensitized patients. Transplantation. 2012; 94:165–171. PMID: 22735712.17. Marfo K, Ling M, Bao Y, et al. Lack of effect in desensitization with intravenous immunoglobulin and rituximab in highly sensitized patients. Transplantation. 2012; 94:345–351. PMID: 22820699.18. Kobashigawa JA, Sabad A, Drinkwater D, et al. Pretransplant panel reactive-antibody screens. Are they truly a marker for poor outcome after cardiac transplantation? Circulation. 1996; 94(Suppl):II294–II297. PMID: 8901763.19. Patel J, Everly M, Chang D, Kittleson M, Reed E, Kobashigawa J. Reduction of alloantibodies via proteasome inhibition in cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011; 30:1320–1326. PMID: 21968130.20. Kwun J, Burghuber C, Manook M, et al. Humoral compensation after bortezomib treatment of allosensitized recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 28:1991–1996. PMID: 28232617.21. Alishetti S, Farr M, Jennings D, et al. Desensitizing highly sensitized heart transplant candidates with the combination of belatacept and proteasome inhibition. Am J Transplant. 2020; 20:3620–3630. PMID: 32506824.22. Sriwattanakomen R, Xu Q, Demehin M, et al. Impact of carfilzomib-based desensitization on heart transplantation of sensitized candidates. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2021; 40:595–603. PMID: 33785250.23. Patel JK, Coutance G, Loupy A, et al. Complement inhibition for prevention of antibody-mediated rejection in immunologically high-risk heart allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2021; 21:2479–2488. PMID: 33251691.24. Jackson KR, Covarrubias K, Holscher CM, et al. The national landscape of deceased donor kidney transplantation for the highly sensitized: Transplant rates, waitlist mortality, and posttransplant survival under KAS. Am J Transplant. 2019; 19:1129–1138. PMID: 30372592.25. Parajuli S, Redfield RR, Astor BC, Djamali A, Kaufman DB, Mandelbrot DA. Outcomes in the highest panel reactive antibody recipients of deceased donor kidneys under the new kidney allocation system. Clin Transplant. 2017; 31:e12895.26. Jaiswal A, Bell J, DeFilippis EM, et al. Assessment and management of allosensitization following heart transplant in adults. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2023; 42:423–432. PMID: 36702686.27. Itescu S, Tung TC, Burke EM, et al. Preformed IgG antibodies against major histocompatibility complex class II antigens are major risk factors for high-grade cellular rejection in recipients of heart transplantation. Circulation. 1998; 98:786–793. PMID: 9727549.28. Suciu-Foca N, Reed E, Marboe C, et al. The role of anti-HLA antibodies in heart transplantation. Transplantation. 1991; 51:716–724. PMID: 2006531.29. Michaels PJ, Espejo ML, Kobashigawa J, et al. Humoral rejection in cardiac transplantation: risk factors, hemodynamic consequences and relationship to transplant coronary artery disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003; 22:58–69. PMID: 12531414.30. Tague LK, Witt CA, Byers DE, et al. Association between allosensitization and waiting list outcomes among adult lung transplant candidates in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019; 16:846–852. PMID: 30763122.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Impacts of pretransplant panel-reactive antibody on posttransplantation outcomes: a study of nationwide heart transplant registry data

- Allograft Immune Reaction of Kidney Transplantation Part 2. Immunosuppression and Methods to Assess Alloimmunity

- Pre- and Post-Transplant Nutritional Assessment in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

- Predictive Value of Donor Specific Antibody Measured by Luminex Single Antigen Assay for Antibody Mediated Rejection after Kidney Transplantation

- Pre- and post-transplant risk factors for renal dysfunction in the patients with preserved renal function at 1 month after liver transplantation: a national cohort study using Korean Organ Transplantation Registry (KOTRY)