Korean J Gastroenterol.

2024 May;83(5):179-183. 10.4166/kjg.2024.039.

Diagnosis of Chronic Constipation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chonnam National University Hospital and Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2555969

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2024.039

Abstract

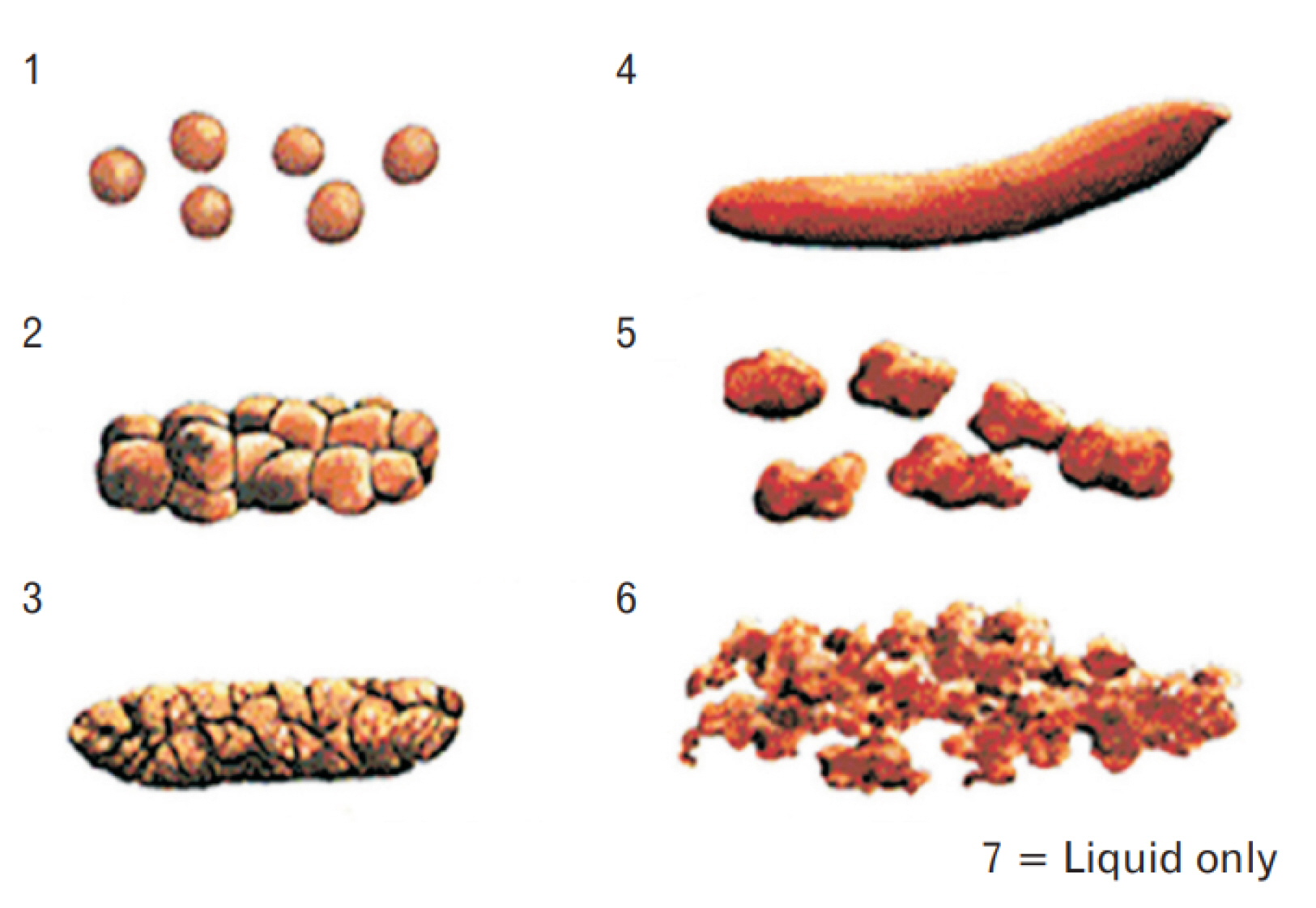

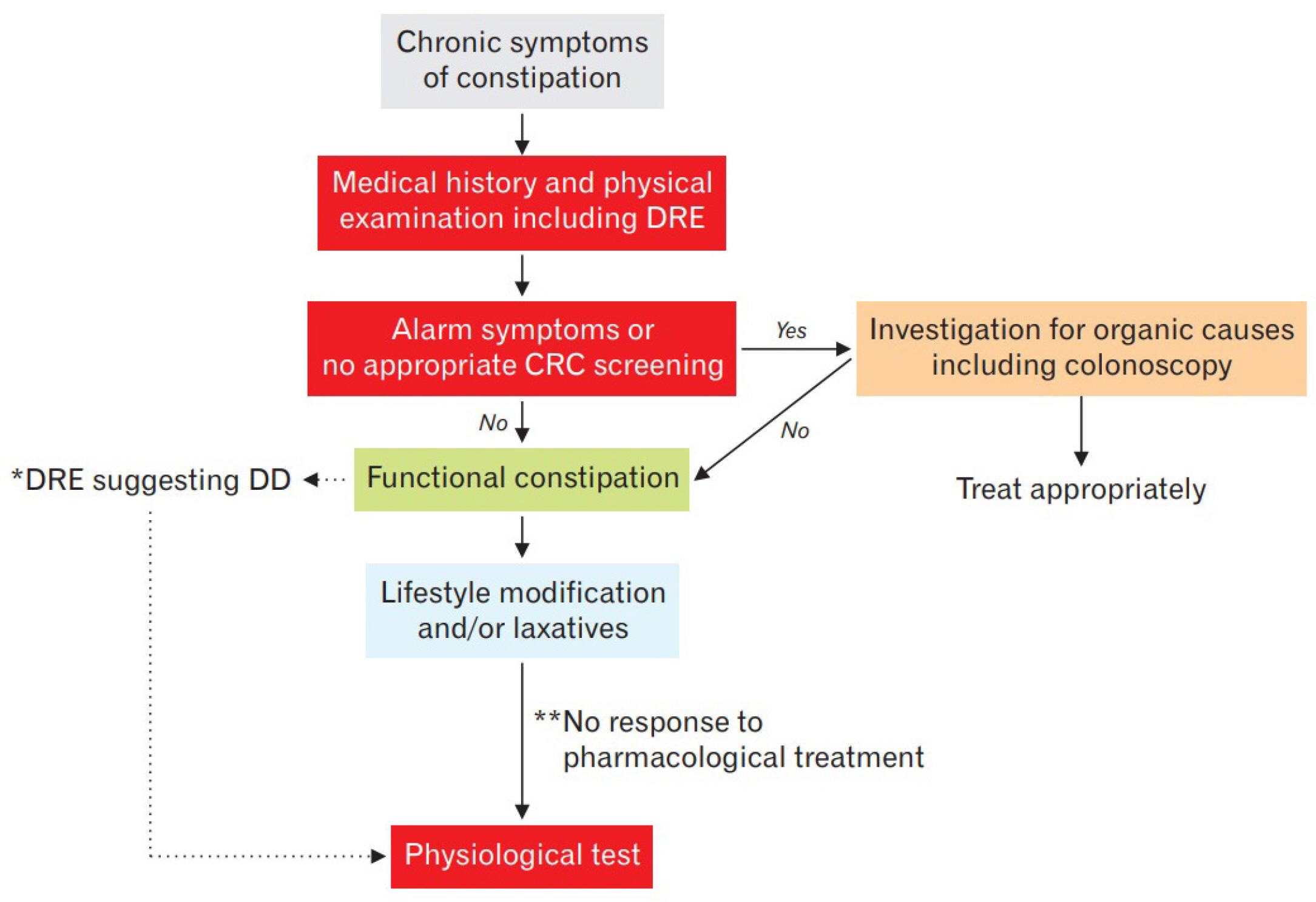

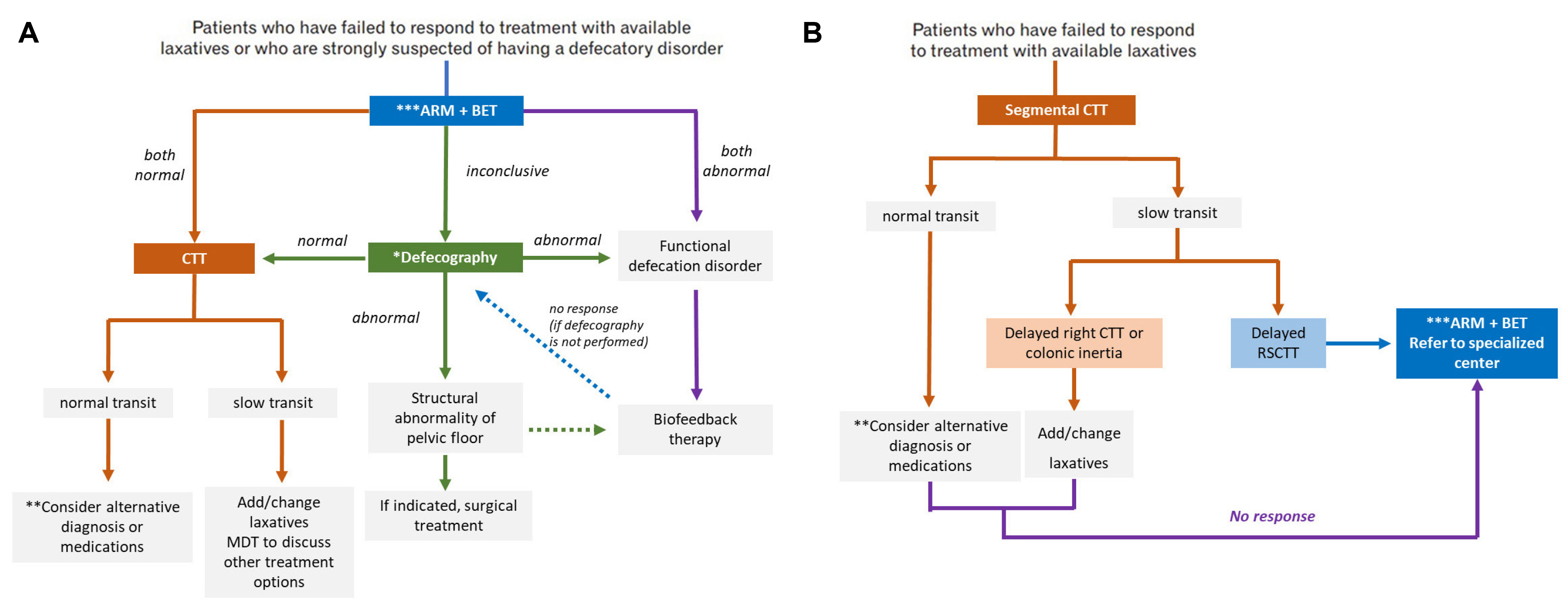

- Patients with chronic constipation (CC) usually complain of mild to severe symptoms, including hard or lumpy stools, straining, a sense of incomplete evacuation after a bowel movement, a feeling of anorectal blockage, the need for digital maneuver to assist defecation, or reduced stool frequency. In clinical practice, healthcare providers need to check for ‘alarm features’ indicative of a colonic malignancy, such as bloody stools, anemia, unexplained weight loss, or new-onset symptoms after 50 years of age. In the Seoul Consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation, the Bristol stool form scale, colonoscopy, and digital rectal examination are useful for objectively evaluating the symptoms and making a differential diagnosis of the secondary cause of constipation. If patients with CC improve to lifestyle modification or first-line therapies, the effort to determine the subtypes of CC is usually not considered. On the other hand, if conventional therapeutic strategies fail, diagnostic testing needs to be considered to distinguish between the different subtypes of functional constipation (normal-transit constipation, slow transit constipation, or defecatory disorder) because these subtypes of constipation have different therapeutic implications and a correct diagnosis is critical. In the Seoul consensus, physiological testing is recommended for patients with functional constipation who have failed to respond to treatment with available laxatives (for a minimum of 12 weeks and recommended a therapeutic regimen) or who are strongly suspected of having a defecatory disorder. The Seoul consensus contains statements of physiological testing, including balloon expulsion test, anorectal manometry, defecography, and colon transit time.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Saad RJ, Rao SS, Koch KL, et al. 2010; Do stool form and frequency correlate with whole-gut and colonic transit? Results from a multicenter study in constipated individuals and healthy controls. Am J Gastroenterol. 105:403–411. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2009.612. PMID: 19888202.2. Degen LP, Phillips SF. 1996; How well does stool form reflect colonic transit? Gut. 39:109–113. DOI: 10.1136/gut.39.1.109. PMID: 8881820. PMCID: PMC1383242.3. Jaruvongvanich V, Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S. 2017; Prediction of delayed colonic transit using bristol stool form and stool frequency in eastern constipated patients: A difference from the West. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 23:561–568. DOI: 10.5056/jnm17022. PMID: 28738452. PMCID: PMC5628989.4. Tantiphlachiva K, Rao P, Attaluri A, Rao SS. 2010; Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 8:955–960. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.031. PMID: 20656061.5. Rao SSC. 2018; Rectal Exam: Yes, it can and should be done in a busy practice! Am J Gastroenterol. 113:635–638. DOI: 10.1038/s41395-018-0006-y. PMID: 29453382.6. Liu J, Lv C, Huang Y, et al. 2021; Digital rectal examination is a valuable bedside tool for detecting dyssynergic defecation: A diagnostic study and a meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021:5685610. DOI: 10.1155/2021/5685610. PMID: 34746041. PMCID: PMC8568520.7. Wong RK, Drossman DA, Bharucha AE, et al. 2012; The digital rectal examination: a multicenter survey of physicians' and students' perceptions and practice patterns. Am J Gastroenterol. 107:1157–1163. DOI: 10.1038/ajg.2012.23. PMID: 22858996.8. Menand JA, Sandhu R, Israel Y, et al. 2024; Digital rectal exams are infrequently performed prior to anorectal manometry. Dig Dis Sci. 69:728–731. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-023-08243-2. PMID: 38170338.9. Song EM, Lee HJ, Jung KW, et al. 2021; Long-term risks of parkinson's disease, surgery, and colorectal cancer in patients with slow-transit constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19:2577–2586.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.08.059. PMID: 32882425.10. Staller K, Olén O, Söderling J, et al. 2022; Chronic constipation as a risk factor for colorectal cancer: Results from a nationwide, case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:1867–1876.e2. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.10.024. PMID: 34687968. PMCID: PMC9018894.11. Serra J, Pohl D, Azpiroz F, et al. 2020; European society of neurogastroenterology and motility guidelines on functional constipation in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 32:e13762. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.13762. PMID: 31756783.12. Soh AYS, Kang JY, Siah KTH, Scarpignato C, Gwee KA. 2018; Searching for a definition for pharmacologically refractory constipation: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 33:564–575. DOI: 10.1111/jgh.13998. PMID: 28960557.13. Shah ED, Farida JD, Menees S, Baker JR, Chey WD. 2018; Examining balloon expulsion testing as an office-based, screening test for dyssynergic defecation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 113:1613–1620. DOI: 10.1038/s41395-018-0230-5. PMID: 30171220.14. Carrington EV, Heinrich H, Knowles CH, et al. 2020; The international anorectal physiology working group (IAPWG) recommendations: Standardized testing protocol and the London classification for disorders of anorectal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 32:e13679. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.13679. PMID: 31407463. PMCID: PMC6923590.15. Mazor Y, Schnitzler M, Jones M, Ejova A, Malcolm A. 2023; The patient with obstructed defecatory symptoms: Management differs considerably between physicians and surgeons. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 35:e14592. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.14592. PMID: 37036403.16. Nullens S, Nelsen T, Camilleri M, et al. 2012; Regional colon transit in patients with dys-synergic defaecation or slow transit in patients with constipation. Gut. 61:1132–1139. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301181. PMID: 22180057. PMCID: PMC3813955.17. Cho YS, Lee YJ, Shin JE, et al. 2023; 2022 Seoul consensus on clinical practice guidelines for functional constipation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 29:271–305. DOI: 10.5056/jnm23066. PMID: 37417257. PMCID: PMC10334201.