Korean J Pain.

2024 Apr;37(2):91-106. 10.3344/kjp.23284.

The complement system: a potential target for the comorbidity of chronic pain and depression

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 2Department of Pain Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 3Department of Cardiology, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- 4Guizhou Key Laboratory of Anesthesia and Organ Protection, Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

- KMID: 2554950

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.23284

Abstract

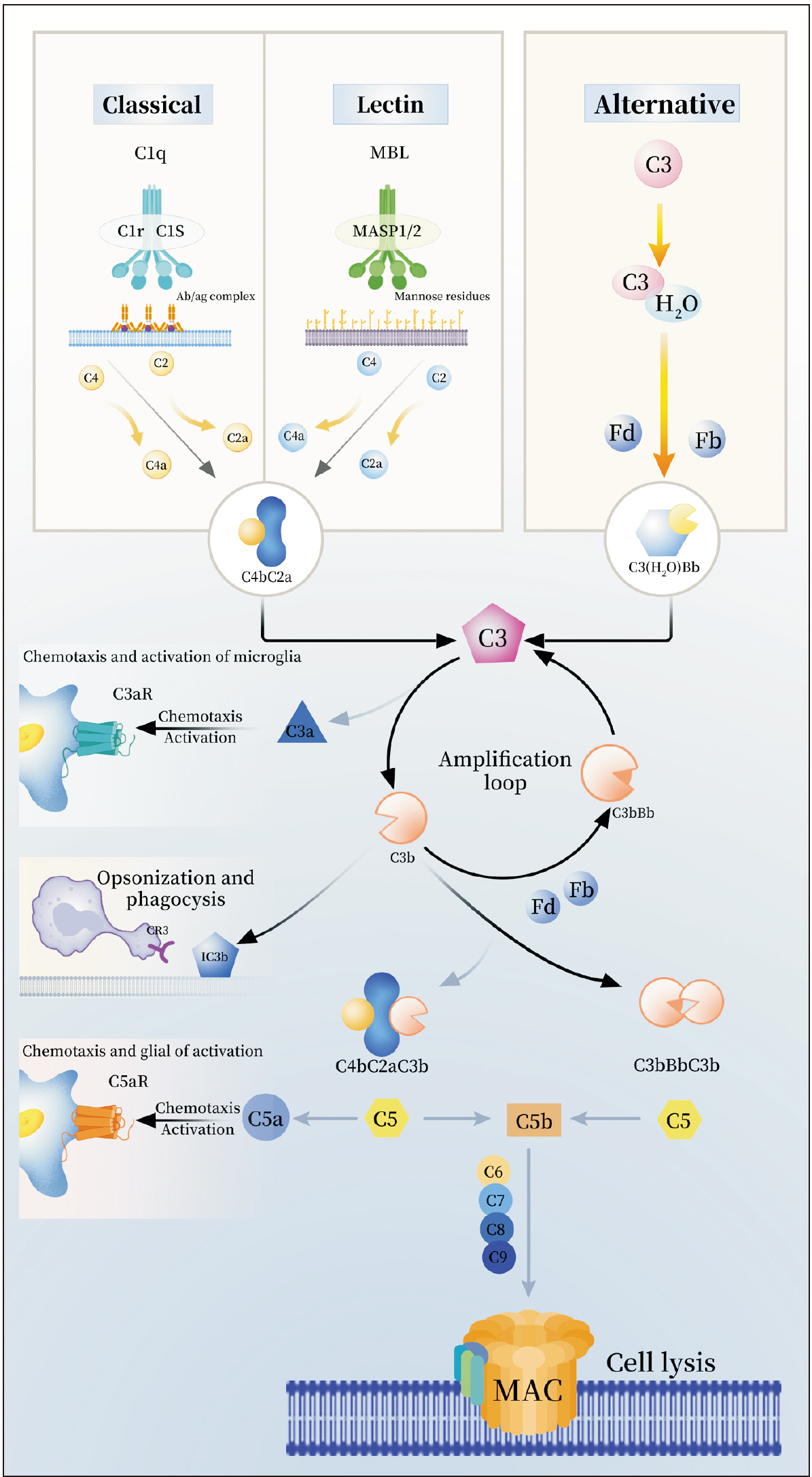

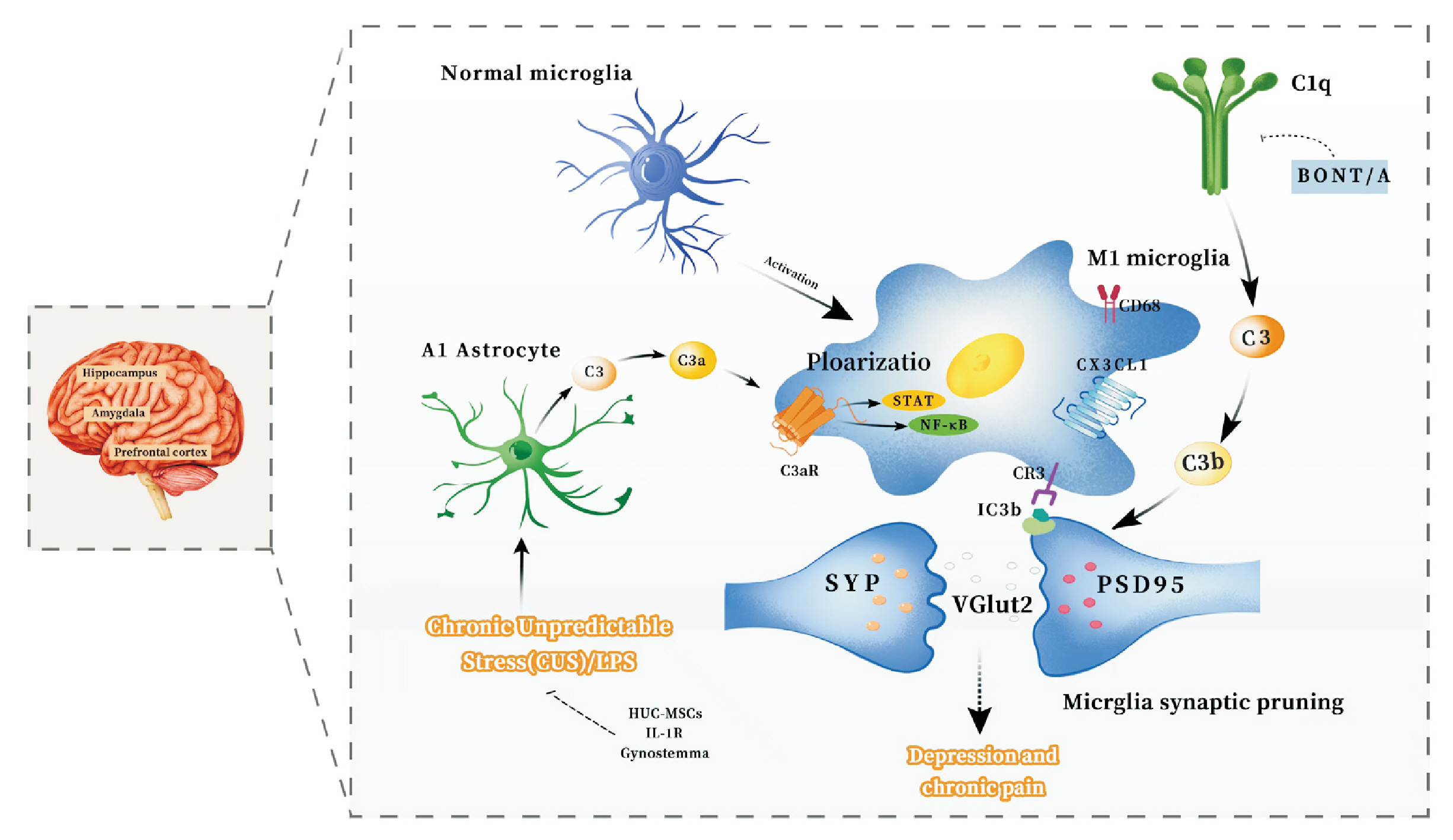

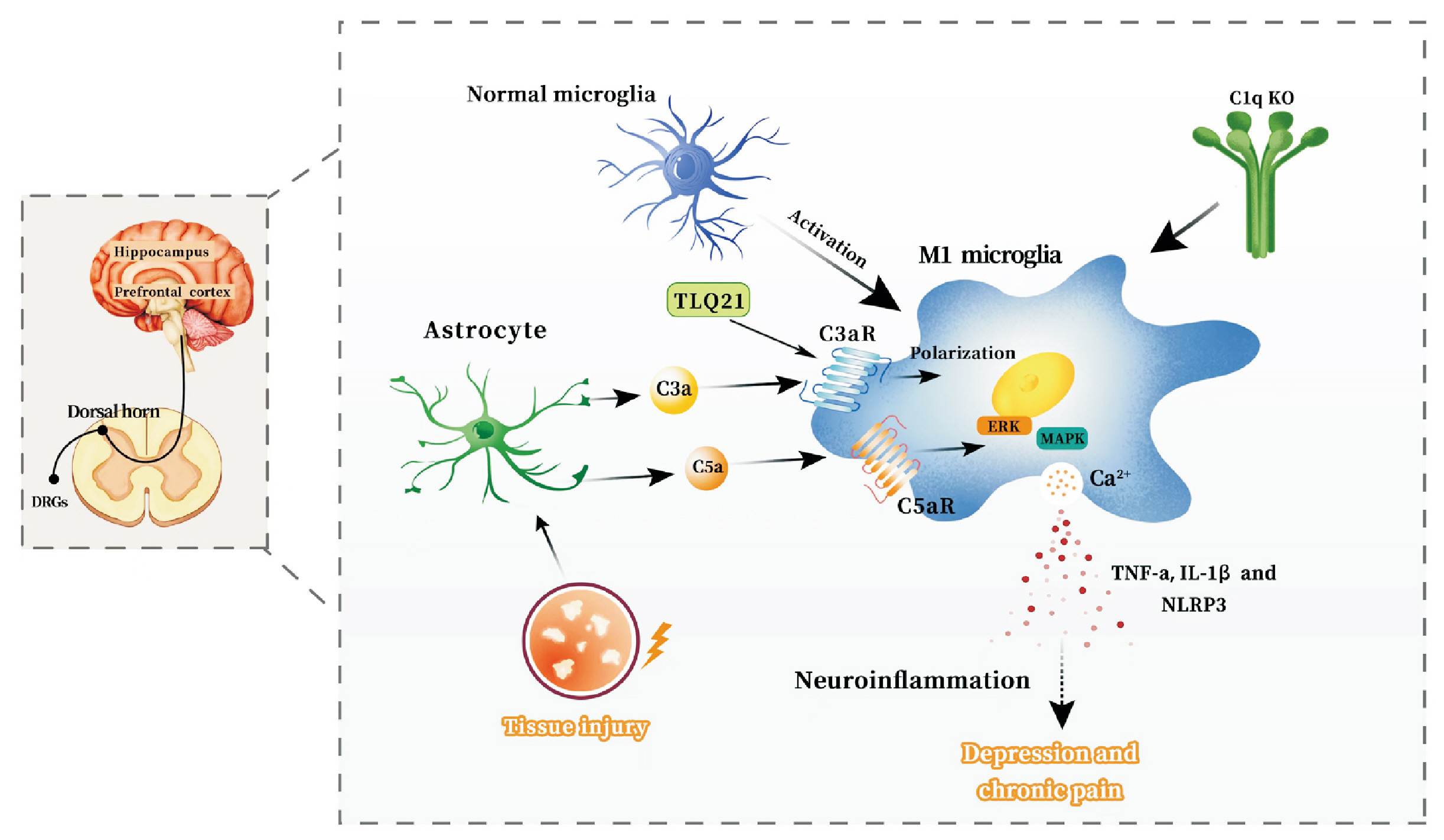

- The mechanisms of the chronic pain and depression comorbidity have gained significant attention in recent years. The complement system, widely involved in central nervous system diseases and mediating non-specific immune mechanisms in the body, remains incompletely understood in its involvement in the comorbidity mechanisms of chronic pain and depression. This review aims to consolidate the findings from recent studies on the complement system in chronic pain and depression, proposing that it may serve as a promising shared therapeutic target for both conditions. Complement proteins C1q, C3, C5, as well as their cleavage products C3a and C5a, along with the associated receptors C3aR, CR3, and C5aR, are believed to have significant implications in the comorbid mechanism. The primary potential mechanisms encompass the involvement of the complement cascade C1q/C3-CR3 in the activation of microglia and synaptic pruning in the amygdala and hippocampus, the role of complement cascade C3/C3a-C3aR in the interaction between astrocytes and microglia, leading to synaptic pruning, and the C3a-C3aR axis and C5a-C5aR axis to trigger inflammation within the central nervous system. We focus on studies on the role of the complement system in the comorbid mechanisms of chronic pain and depression.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. 2020; The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 161:1976–82. DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939. PMID: 32694387. PMCID: PMC7680716.

Article2. Barroso J, Branco P, Apkarian AV. 2021; Brain mechanisms of chronic pain: critical role of translational approach. Transl Res. 238:76–89. DOI: 10.1016/j.trsl.2021.06.004. PMID: 34182187. PMCID: PMC8572168.

Article3. Attal N, Lanteri-Minet M, Laurent B, Fermanian J, Bouhassira D. 2011; The specific disease burden of neuropathic pain: results of a French nationwide survey. Pain. 152:2836–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.014. PMID: 22019149.

Article4. Rizvi SJ, Gandhi W, Salomons T. 2021; Reward processing as a common diathesis for chronic pain and depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 127:749–60. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.04.033. PMID: 33951413.

Article5. Zhou W, Jin Y, Meng Q, Zhu X, Bai T, Tian Y, et al. 2019; A neural circuit for comorbid depressive symptoms in chronic pain. Nat Neurosci. 22:1649–58. Erratum in: Nat Neurosci 2019; 22: 1945. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-019-0468-2. PMID: 31451801.

Article6. Pillai A. 2022; Chronic stress and complement system in depression. Braz J Psychiatry. 44:366–7. DOI: 10.47626/1516-4446-2022-2463. PMID: 35729065. PMCID: PMC9375666.

Article7. Perlmutter DH, Colten HR. 1986; Molecular immunobiology of complement biosynthesis: a model of single-cell control of effector-inhibitor balance. Annu Rev Immunol. 4:231–51. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.001311. PMID: 3518744.

Article8. Singhrao SK, Neal JW, Rushmere NK, Morgan BP, Gasque P. 1999; Differential expression of individual complement regulators in the brain and choroid plexus. Lab Invest. 79:1247–59.9. Zhang W, Chen Y, Pei H. 2023; C1q and central nervous system disorders. Front Immunol. 14:1145649. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1145649. PMID: 37033981. PMCID: PMC10076750.

Article10. Warwick CA, Keyes AL, Woodruff TM, Usachev YM. 2021; The complement cascade in the regulation of neuroinflammation, nociceptive sensitization, and pain. J Biol Chem. 297:101085. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101085. PMID: 34411562. PMCID: PMC8446806.

Article11. Tong Y, Liu J, Yang T, Wang J, Zhao T, Kang Y, et al. 2022; Association of pain with plasma C5a in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders during remission. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 18:1039–46. DOI: 10.2147/NDT.S359620. PMID: 35615424. PMCID: PMC9124695.

Article12. Togha M, Rahimi P, Farajzadeh A, Ghorbani Z, Faridi N, Zahra Bathaie S. 2022; Proteomics analysis revealed the presence of inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in the plasma of migraine patients during the pain period. Brain Res. 1797:148100. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2022.148100. PMID: 36174672.

Article13. Yi D, Wang K, Zhu B, Li S, Liu X. 2021; Identification of neuropathic pain-associated genes and pathways via random walk with restart algorithm. J Neurosurg Sci. 65:414–20. DOI: 10.23736/S0390-5616.20.04920-6. PMID: 32536116.

Article14. Wang K, Yi D, Yu Z, Zhu B, Li S, Liu X. 2020; Identification of the hub genes related to nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Front Neurosci. 14:488. DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00488. PMID: 32508579. PMCID: PMC7251260.

Article15. Zhou J, Li J, Ma L, Cao S. 2020; Zoster sine herpete: a review. Korean J Pain. 33:208–15. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2020.33.3.208. PMID: 32606265. PMCID: PMC7336347.

Article16. Peng Z, Guo J, Zhang Y, Guo X, Huang W, Li Y, et al. 2022; Development of a model for predicting the effectiveness of pulsed radiofrequency on zoster-associated pain. Pain Ther. 11:253–67. DOI: 10.1007/s40122-022-00355-3. PMID: 35094299. PMCID: PMC8861232.

Article17. Reddy PV, Talukdar PM, Subbanna M, Bhargav PH, Arasappa R, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. 2023; Multiple complement pathway-related proteins might regulate immunopathogenesis of major depressive disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 21:313–9. DOI: 10.9758/cpn.2023.21.2.313. PMID: 37119224. PMCID: PMC10157013.

Article18. Luo X, Fang Z, Lin L, Xu H, Huang Q, Zhang H. 2022; Plasma complement C3 and C3a are increased in major depressive disorder independent of childhood trauma. BMC Psychiatry. 22:741. DOI: 10.1186/s12888-022-04410-3. PMID: 36447174. PMCID: PMC9706857.

Article19. Yao Q, Li Y. 2020; Increased serum levels of complement C1q in major depressive disorder. J Psychosom Res. 133:110105. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110105. PMID: 32272297.

Article20. Crider A, Feng T, Pandya CD, Davis T, Nair A, Ahmed AO, et al. 2018; Complement component 3a receptor deficiency attenuates chronic stress-induced monocyte infiltration and depressive-like behavior. Brain Behav Immun. 70:246–56. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.03.004. PMID: 29518530. PMCID: PMC5967612.

Article21. Westacott LJ, Humby T, Haan N, Brain SA, Bush EL, Toneva M, et al. 2022; Complement C3 and C3aR mediate different aspects of emotional behaviours; relevance to risk for psychiatric disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 99:70–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.09.005. PMID: 34543680.

Article22. Tripathi A, Whitehead C, Surrao K, Pillai A, Madeshiya A, Li Y, et al. 2021; Type 1 interferon mediates chronic stress-induced neuroinflammation and behavioral deficits via complement component 3-dependent pathway. Mol Psychiatry. 26:3043–59. DOI: 10.1038/s41380-021-01065-6. PMID: 33833372. PMCID: PMC8497654.

Article23. Griffin RS, Costigan M, Brenner GJ, Ma CH, Scholz J, Moss A, et al. 2007; Complement induction in spinal cord microglia results in anaphylatoxin C5a-mediated pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 27:8699–708. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2018-07.2007. PMID: 17687047. PMCID: PMC6672952.

Article24. Davoust N, Jones J, Stahel PF, Ames RS, Barnum SR. 1999; Receptor for the C3a anaphylatoxin is expressed by neurons and glial cells. Glia. 26:201–11. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199905)26:3<201::AID-GLIA2>3.0.CO;2-M.

Article25. Zhang MM, Guo MX, Zhang QP, Chen XQ, Li NZ, Liu Q, et al. 2022; IL-1R/C3aR signaling regulates synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex of depression. Cell Biosci. 12:90. DOI: 10.1186/s13578-022-00832-4. PMID: 35715851. PMCID: PMC9205119.

Article26. Quadros AU, Cunha TM. 2016; C5a and pain development: an old molecule, a new target. Pharmacol Res. 112:58–67. DOI: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.02.004. PMID: 26855316.

Article27. Yasuda M, Nagappan-Chettiar S, Johnson-Venkatesh EM, Umemori H. 2021; An activity-dependent determinant of synapse elimination in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 109:1333–49.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.03.006. PMID: 33770504. PMCID: PMC8068677.

Article28. Soteros BM, Sia GM. 2022; Complement and microglia dependent synapse elimination in brain development. WIREs Mech Dis. 14:e1545. DOI: 10.1002/wsbm.1545. PMID: 34738335. PMCID: PMC9066608.

Article29. De Leo JA, Tawfik VL, LaCroix-Fralish ML. 2006; The tetrapartite synapse: path to CNS sensitization and chronic pain. Pain. 122:17–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.034. PMID: 16564626.

Article30. Deng SL, Chen JG, Wang F. 2020; Microglia: a central player in depression. Curr Med Sci. 40:391–400. DOI: 10.1007/s11596-020-2193-1. PMID: 32681244.

Article31. Lawal O, Ulloa Severino FP, Eroglu C. 2022; The role of astrocyte structural plasticity in regulating neural circuit function and behavior. Glia. 70:1467–83. DOI: 10.1002/glia.24191. PMID: 35535566. PMCID: PMC9233050.

Article32. Dejanovic B, Wu T, Tsai MC, Graykowski D, Gandham VD, Rose CM, et al. 2022; Complement C1q-dependent excitatory and inhibitory synapse elimination by astrocytes and microglia in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat Aging. 2:837–50. DOI: 10.1038/s43587-022-00281-1. PMID: 37118504. PMCID: PMC10154216.

Article33. Filipello F, Morini R, Corradini I, Zerbi V, Canzi A, Michalski B, et al. 2018; The microglial innate immune receptor TREM2 is required for synapse elimination and normal brain connectivity. Immunity. 48:979–91.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.016. PMID: 29752066.

Article34. Schecter RW, Maher EE, Welsh CA, Stevens B, Erisir A, Bear MF. 2017; Experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in V1 occurs without microglial CX3CR1. J Neurosci. 37:10541–53. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2679-16.2017. PMID: 28951447. PMCID: PMC5666579.

Article35. Chung WS, Clarke LE, Wang GX, Stafford BK, Sher A, Chakraborty C, et al. 2013; Astrocytes mediate synapse elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK pathways. Nature. 504:394–400. DOI: 10.1038/nature12776. PMID: 24270812. PMCID: PMC3969024.

Article36. Lee JH, Kim JY, Noh S, Lee H, Lee SY, Mun JY, et al. 2021; Astrocytes phagocytose adult hippocampal synapses for circuit homeostasis. Nature. 590:612–7. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-03060-3. PMID: 33361813.

Article37. Brown GC, Neher JJ. 2014; Microglial phagocytosis of live neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 15:209–16. DOI: 10.1038/nrn3710. PMID: 24646669.

Article38. Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, Nouri N, et al. 2007; The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 131:1164–78. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036. PMID: 18083105.

Article39. Cong Q, Soteros BM, Wollet M, Kim JH, Sia GM. 2020; The endogenous neuronal complement inhibitor SRPX2 protects against complement-mediated synapse elimination during development. Nat Neurosci. 23:1067–78. DOI: 10.1038/s41593-020-0672-0. PMID: 32661396. PMCID: PMC7483802.

Article40. Lehrman EK, Wilton DK, Litvina EY, Welsh CA, Chang ST, Frouin A, et al. 2018; CD47 protects synapses from excess microglia-mediated pruning during development. Neuron. 100:120–34.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.017. PMID: 30308165. PMCID: PMC6314207.

Article41. Lian H, Litvinchuk A, Chiang AC, Aithmitti N, Jankowsky JL, Zheng H. 2016; Astrocyte-microglia cross talk through complement activation modulates amyloid pathology in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 36:577–89. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2117-15.2016. PMID: 26758846. PMCID: PMC4710776.

Article42. Park SY, Kim IS. 2017; Engulfment signals and the phagocytic machinery for apoptotic cell clearance. Exp Mol Med. 49:e331. DOI: 10.1038/emm.2017.52. PMID: 28496201. PMCID: PMC5454446.

Article43. Fonseca MI, Chu SH, Hernandez MX, Fang MJ, Modarresi L, Selvan P, et al. 2017; Cell-specific deletion of C1qa identifies microglia as the dominant source of C1q in mouse brain. J Neuroinflammation. 14:48. DOI: 10.1186/s12974-017-0814-9. PMID: 28264694. PMCID: PMC5340039.

Article44. Lu JH, Teh BK, Wang Ld, Wang YN, Tan YS, Lai MC, et al. 2008; The classical and regulatory functions of C1q in immunity and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 5:9–21. DOI: 10.1038/cmi.2008.2. PMID: 18318990. PMCID: PMC4652917.

Article45. Györffy BA, Kun J, Török G, Bulyáki É, Borhegyi Z, Gulyássy P, et al. 2018; Local apoptotic-like mechanisms underlie complement-mediated synaptic pruning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 115:6303–8. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1722613115. PMID: 29844190. PMCID: PMC6004452.

Article46. Dunkelberger JR, Song WC. 2010; Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 20:34–50. DOI: 10.1038/cr.2009.139. PMID: 20010915.

Article47. Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. 2016; Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science. 352:712–6. DOI: 10.1126/science.aad8373. PMID: 27033548. PMCID: PMC5094372.

Article48. Wang R, Wang Q, Xie T, Guo K. 2021; The role of glial cell activation mediated by complement system C1q/C3 in depression-like behavior in mice. J SUN Yat-sen Univ (Med Sci). 42:328–37.49. Li Y, Yin Q, Li Q, Huo AR, Shen TT, Cao JQ, et al. 2023; Botulinum neurotoxin A ameliorates depressive-like behavior in a reserpine-induced Parkinson's disease mouse model via suppressing hippocampal microglial engulfment and neuroinflammation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 44:1322–36. DOI: 10.1038/s41401-023-01058-x. PMID: 36765267. PMCID: PMC10310724.

Article50. Yuan T, Orock A, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. 2021; Amygdala microglia modify neuronal plasticity via complement C1q/C3-CR3 signaling and contribute to visceral pain in a rat model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 320:G1081–92. DOI: 10.1152/ajpgi.00123.2021. PMID: 33949202.

Article51. Coulthard LG, Hawksworth OA, Conroy J, Lee JD, Woodruff TM. 2018; Complement C3a receptor modulates embryonic neural progenitor cell proliferation and cognitive performance. Mol Immunol. 101:176–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.06.271. PMID: 30449309.

Article52. Coulthard LG, Woodruff TM. 2015; Is the complement activation product C3a a proinflammatory molecule? Re-evaluating the evidence and the myth. J Immunol. 194:3542–8. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403068. PMID: 25848071.

Article53. Li J, Wang H, Du C, Jin X, Geng Y, Han B, et al. 2020; hUC-MSCs ameliorated CUMS-induced depression by modulating complement C3 signaling-mediated microglial polarization during astrocyte-microglia crosstalk. Brain Res Bull. 163:109–19. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2020.07.004. PMID: 32681971.

Article54. Zhang MM, Huo GM, Cheng J, Zhang QP, Li NZ, Guo MX, et al. 2022; Gypenoside XVII, an active ingredient from Gynostemma pentaphyllum, inhibits C3aR-associated synaptic pruning in stressed mice. Nutrients. 14:2418. DOI: 10.3390/nu14122418. PMID: 35745148. PMCID: PMC9228113.

Article55. Nie F, Wang J, Su D, Shi Y, Chen J, Wang H, et al. 2013; Abnormal activation of complement C3 in the spinal dorsal horn is closely associated with progression of neuropathic pain. Int J Mol Med. 31:1333–42. DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1344. PMID: 23588254.

Article56. Mou W, Ma L, Zhu A, Cui H, Huang Y. 2022; Astrocyte-microglia interaction through C3/C3aR pathway modulates neuropathic pain in rats model of chronic constriction injury. Mol Pain. 18:17448069221140532. DOI: 10.1177/17448069221140532. PMID: 36341694. PMCID: PMC9669679.

Article57. Zhu A, Cui H, Su W, Liu C, Yu X, Huang Y. 2023; C3aR in astrocytes mediates post-thoracotomy pain by inducing A1 astrocytes in male rats. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1869:166672. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166672. PMID: 36871753.

Article58. Andersen SL. 2022; Neuroinflammation, early-life adversity, and brain development. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 30:24–39. DOI: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000325. PMID: 34995033. PMCID: PMC8820591.

Article59. Campos ACP, Antunes GF, Matsumoto M, Pagano RL, Martinez RCR. 2020; Neuroinflammation, pain and depression: an overview of the main findings. Front Psychol. 11:1825. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01825. PMID: 32849076. PMCID: PMC7412934.

Article60. Burke NN, Finn DP, Roche M. 2015; Neuroinflammatory mechanisms linking pain and depression. Mod Trends Pharmacopsychiatry. 30:36–50. DOI: 10.1159/000435931. PMID: 26437255.

Article61. Guo B, Zhang M, Hao W, Wang Y, Zhang T, Liu C. 2023; Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Transl Psychiatry. 13:5. DOI: 10.1038/s41398-022-02297-y. PMID: 36624089. PMCID: PMC9829236.

Article62. Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. 2010; Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 11:785–97. DOI: 10.1038/ni.1923. PMID: 20720586. PMCID: PMC2924908.

Article63. Bohlson SS, Tenner AJ. 2023; Complement in the brain: contributions to neuroprotection, neuronal plasticity, and neuroinflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 41:431–52. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101921-035639. PMID: 36750318.

Article64. Schartz ND, Tenner AJ. 2020; The good, the bad, and the opportunities of the complement system in neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation. 17:354. DOI: 10.1186/s12974-020-02024-8. PMID: 33239010. PMCID: PMC7690210.

Article65. Wu X, Gao Y, Shi C, Tong J, Ma D, Shen J, et al. 2023; Complement C1q drives microglia-dependent synaptic loss and cognitive impairments in a mouse model of lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation. Neuropharmacology. 237:109646. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2023.109646. PMID: 37356797.

Article66. Zhou R, Chen SH, Zhao Z, Tu D, Song S, Wang Y, et al. 2023; Complement C3 enhances LPS-elicited neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration via the Mac1/NOX2 pathway. Mol Neurobiol. 60:5167–83. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-023-03393-w. PMID: 37268807. PMCID: PMC10415527.

Article67. Veerhuis R, Boshuizen RS, Morbin M, Mazzoleni G, Hoozemans JJ, Langedijk JP, et al. 2005; Activation of human microglia by fibrillar prion protein-related peptides is enhanced by amyloid-associated factors SAP and C1q. Neurobiol Dis. 19:273–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.005. PMID: 15837583.

Article68. Madeshiya AK, Whitehead C, Tripathi A, Pillai A. 2022; C1q deletion exacerbates stress-induced learned helplessness behavior and induces neuroinflammation in mice. Transl Psychiatry. 12:50. DOI: 10.1038/s41398-022-01794-4. PMID: 35105860. PMCID: PMC8807734.

Article69. Simonetti M, Hagenston AM, Vardeh D, Freitag HE, Mauceri D, Lu J, et al. 2013; Nuclear calcium signaling in spinal neurons drives a genomic program required for persistent inflammatory pain. Neuron. 77:43–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.037. PMID: 23312515. PMCID: PMC3593630.

Article70. Lee JD, Coulthard LG, Woodruff TM. 2019; Complement dysregulation in the central nervous system during development and disease. Semin Immunol. 45:101340. DOI: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101340. PMID: 31708347.

Article71. Tenner AJ. 2020; Complement-mediated events in Alzheimer's disease: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J Immunol. 204:306–15. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901068. PMID: 31907273. PMCID: PMC6951444.

Article72. Liu Y, Xu SQ, Long WJ, Zhang XY, Lu HL. 2018; C5aR antagonist inhibits occurrence and progression of complement C5a induced inflammatory response of microglial cells through activating p38MAPK and ERK1/2 signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 22:7994–8003.73. Doolen S, Cook J, Riedl M, Kitto K, Kohsaka S, Honda CN, et al. 2017; Complement 3a receptor in dorsal horn microglia mediates pronociceptive neuropeptide signaling. Glia. 65:1976–89. DOI: 10.1002/glia.23208. PMID: 28850719. PMCID: PMC5747931.

Article74. Li J, Tian S, Wang H, Wang Y, Du C, Fang J, et al. 2021; Protection of hUC-MSCs against neuronal complement C3a receptor-mediated NLRP3 activation in CUMS-induced mice. Neurosci Lett. 741:135485. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135485. PMID: 33161108.

Article75. Morgan M, Deuis JR, Woodruff TM, Lewis RJ, Vetter I. 2018; Role of complement anaphylatoxin receptors in a mouse model of acute burn-induced pain. Mol Immunol. 94:68–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.12.016. PMID: 29274925.

Article76. Reginia A, Kucharska-Mazur J, Jabłoński M, Budkowska M, Dołȩgowska B, Sagan L, et al. 2018; Assessment of complement cascade components in patients with bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 9:614. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00614. PMID: 30538645. PMCID: PMC6277457.

Article77. Ishii T, Hattori K, Miyakawa T, Watanabe K, Hidese S, Sasayama D, et al. 2018; Increased cerebrospinal fluid complement C5 levels in major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 497:683–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.131. PMID: 29454970.

Article78. Alexander JJ. 2018; Blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the complement landscape. Mol Immunol. 102:26–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.06.267. PMID: 30007547.

Article79. Alexander JJ, Anderson AJ, Barnum SR, Stevens B, Tenner AJ. 2008; The complement cascade: Yin-Yang in neuroinflammation--neuro-protection and -degeneration. J Neurochem. 107:1169–87. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05668.x. PMID: 18786171. PMCID: PMC4038542.80. Sprong T, Brandtzaeg P, Fung M, Pharo AM, Høiby EA, Michaelsen TE, et al. 2003; Inhibition of C5a-induced inflammation with preserved C5b-9-mediated bactericidal activity in a human whole blood model of meningococcal sepsis. Blood. 102:3702–10. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0703. PMID: 12881318.

Article81. Paczkowski NJ, Finch AM, Whitmore JB, Short AJ, Wong AK, Monk PN, et al. 1999; Pharmacological characterization of antagonists of the C5a receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 128:1461–6. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702938. PMID: 10602324. PMCID: PMC1571783.

Article82. Ricklin D, Lambris JD. 2007; Complement-targeted therapeutics. Nat Biotechnol. 25:1265–75. DOI: 10.1038/nbt1342. PMID: 17989689. PMCID: PMC2966895.

Article83. Tamamis P, Kieslich CA, Nikiforovich GV, Woodruff TM, Morikis D, Archontis G. 2014; Insights into the mechanism of C5aR inhibition by PMX53 via implicit solvent molecular dynamics simulations and docking. BMC Biophys. 7:5. DOI: 10.1186/2046-1682-7-5. PMID: 25170421. PMCID: PMC4141665.

Article84. Moriconi A, Cunha TM, Souza GR, Lopes AH, Cunha FQ, Carneiro VL, et al. 2014; Targeting the minor pocket of C5aR for the rational design of an oral allosteric inhibitor for inflammatory and neuropathic pain relief. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 111:16937–42. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1417365111. PMID: 25385614. PMCID: PMC4250151.

Article85. Vicente B, Saldivia S, Hormazabal N, Bustos C, Rubí P. 2020; Etifoxine is non-inferior than clonazepam for reduction of anxiety symptoms in the treatment of anxiety disorders: a randomized, double blind, non-inferiority trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 237:3357–67. DOI: 10.1007/s00213-020-05617-6. PMID: 33009629.

Article86. Fairley LH, Sahara N, Aoki I, Ji B, Suhara T, Higuchi M, et al. 2021; Neuroprotective effect of mitochondrial translocator protein ligand in a mouse model of tauopathy. J Neuroinflammation. 18:76. DOI: 10.1186/s12974-021-02122-1. PMID: 33740987. PMCID: PMC7980620.

Article87. Rupprecht R, Rupprecht C, Di Benedetto B, Rammes G. 2022; Neuroinflammation and psychiatric disorders: relevance of C1q, translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO), and neurosteroids. World J Biol Psychiatry. 23:257–63. DOI: 10.1080/15622975.2021.1961503. PMID: 34320915.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Anesthetic management of living donor liver transplantation for complement factor H deficiency hemolytic uremic syndrome: a case report

- Role of Complement in Bronchial Asthma

- Electroconvulsive therapy for CRPS with depression: A case report

- Severity of Stressful Life Events, Depression and Immune Function

- Alternative and Complement Therapies for Asthma