J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Apr;39(13):e125. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e125.

Understanding the Fluctuations in Korea’s Suicide Rates: A Change-Point Analysis and Interrupted Time Series Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

- 2Gwangju Metropolitan Mental Health Welfare Center, Gwangju, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Seoul Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 4Mindlink, Gwangju Bukgu Mental Health Center, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2554579

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e125

Abstract

- Background

Korea has witnessed significant fluctuations in its suicide rates in recent decades, which may be related to modifications in its death registration system. This study aimed to explore the structural shifts in suicide trends, as well as accidental and ill-defined deaths in Korea, and to analyze the patterns of these changes.

Methods

We analyzed age-adjusted death rates for suicides, deaths due to transport accidents, falls, drowning, fire-related incidents, poisonings, other external causes, and ill-defined deaths in Korea from 1997 to 2021. We identified change-points using the ‘breakpoints’ function from the ‘strucchange’ package and conducted interrupted time series analyses to assess trends before and after these change-points.

Results

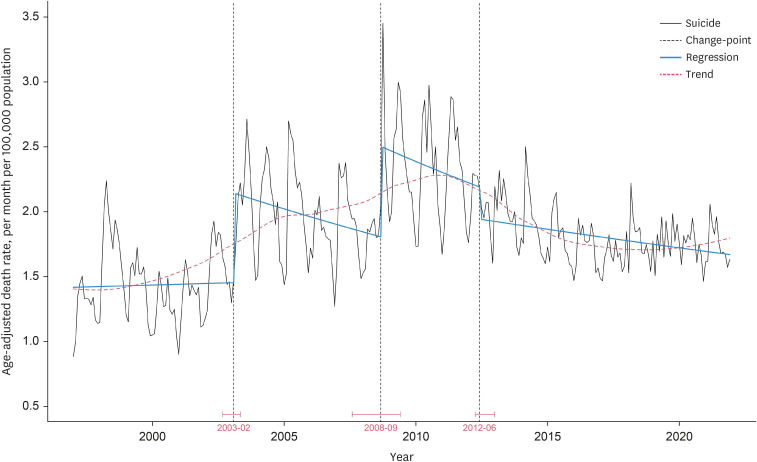

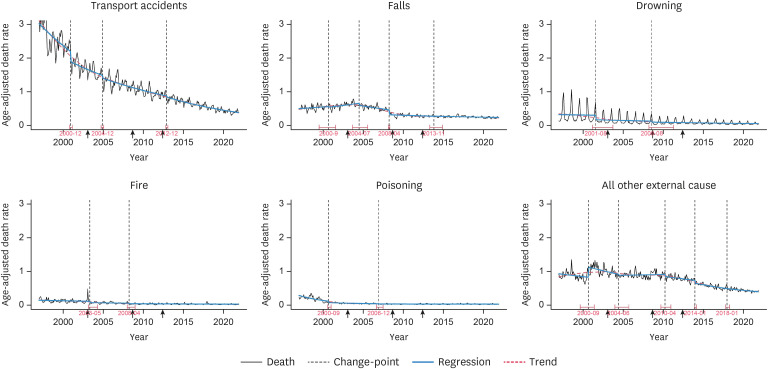

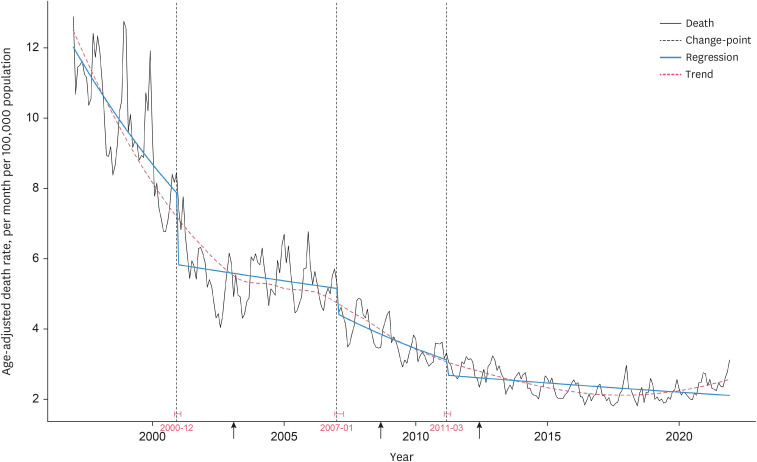

Korea’s suicide rates had three change-points in February 2003, September 2008, and June 2012, characterized by stair-step changes, with level jumps at the 2003 and 2008 change-points and a sharp decline at the 2012 change-point. Notably, the 2003 and 2008 spikes roughly coincided with modifications to the death ascertainment process. The trend in suicide rates showed a downward slope within the 2003–2008 and 2008–2012 periods. Furthermore, ill-defined deaths and most accidental deaths decreased rapidly through several change-points in the early and mid-2000s.

Conclusion

The marked fluctuations in Korea’s suicide rate during the 2000s may be largely attributed to improvements in suicide classification, with potential implications beyond socio-economic factors. These findings suggest that the actual prevalence of suicides in Korea in the 2000s might have been considerably higher than officially reported.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kim SW, Yoon JS. Suicide, an urgent health issue in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013; 28(3):345–347. PMID: 23487589.2. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Suicide rates. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/suicide-rates.htm .3. Kwon JW, Chun H, Cho SI. A closer look at the increase in suicide rates in South Korea from 1986-2005. BMC Public Health. 2009; 9(1):72. PMID: 19250535.4. Lee SU, Park JI, Lee S, Oh IH, Choi JM, Oh CM. Changing trends in suicide rates in South Korea from 1993 to 2016: a descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2018; 8(9):e023144.5. Statistics Korea. Deaths by cause. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://kosis.kr/eng/ .6. Bremberg SG. Suicide rates in European OECD nations converged during the period 1990-2010. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017; 52(5):559–562. PMID: 28260127.7. Kino S, Jang SN, Gero K, Kato S, Kawachi I. Age, period, cohort trends of suicide in Japan and Korea (1986-2015): a tale of two countries. Soc Sci Med. 2019; 235:112385. PMID: 31276968.8. Lies E. Japanese suicides decline to lowest in over 40 years. Reuters;Updated 2020. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN1ZG0NI/ .9. Ilic M, Ilic I. Worldwide suicide mortality trends (2000-2019): a joinpoint regression analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2022; 12(8):1044–1060. PMID: 36158305.10. Jang H, Lee W, Kim YO, Kim H. Suicide rate and social environment characteristics in South Korea: the roles of socioeconomic, demographic, urbanicity, general health behaviors, and other environmental factors on suicide rate. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):410. PMID: 35227243.11. Im JS, Park BC, Ratcliff KS. Cultural stigma manifested in official suicide death in South Korea. Omega. 2018; 77(4):386–403. PMID: 30035706.12. Im JS, Kim CH, Kim CK, Seo HC, Hong DH, Lee SY, et al. Study on Investigating Suicide Causes and Developing Suicide Prevention Programs in Korea. Sejong, Korea: Gachon University of Medicine and Science;2008.13. Chan CH, Caine ED, Chang SS, Lee WJ, Cha ES, Yip PS. The impact of improving suicide death classification in South Korea: a comparison with Japan and Hong Kong. PLoS One. 2015; 10(5):e0125730. PMID: 25992879.14. Sharma S, Swayne DA, Obimbo C. Trend analysis and change point techniques: a survey. Energy Ecol Environ. 2016; 1(3):123–130.15. Statistics Korea. Microdata integrated service. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://mdis.kostat.go.kr/eng/index.do .16. World Health Organization. ICD-10 version:2019. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en .17. Silvi J. On the estimation of mortality rates for countries of the Americas. Epidemiol Bull. 2003; 24(4):1–5.18. Statistics Korea. Population statistics based on resident registration. Updated 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://kosis.kr/eng/ .19. Zeileis A. Package ‘strucchange’. Updated 2022. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/strucchange/strucchange.pdf .20. Otto SA. Comparison of change point detection methods. Updated 2019. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://www.marinedatascience.co/blog/2019/09/28/comparison-of-change-point-detection-methods/ .21. Lecy J, Fusi F. Interrupted time series. Updated 2020. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://ds4ps.org/pe4ps-textbook/docs/p-020-time-series.html .22. Taylor W. Change-point analysis: a powerful new tool for detecting changes. Updated 2018. Accessed September 28, 2023. http://www.variation.com/cpa/tech/changepoint.html .23. Myung W, Lee GH, Won HH, Fava M, Mischoulon D, Nyer M, et al. Paraquat prohibition and change in the suicide rate and methods in South Korea. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6):e0128980. PMID: 26035175.24. Gusmão R, Ramalheira C, Conceição V, Severo M, Mesquita E, Xavier M, et al. Suicide time-series structural change analysis in Portugal (1913-2018): impact of register bias on suicide trends. J Affect Disord. 2021; 291:65–75. PMID: 34023749.25. Chan CH, Caine ED, You S, Fu KW, Chang SS, Yip PS. Suicide rates among working-age adults in South Korea before and after the 2008 economic crisis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014; 68(3):246–252. PMID: 24248999.26. Kim AM. Factors associated with the suicide rates in Korea. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 284:112745. PMID: 31951868.27. Kim H, Song YJ, Yi JJ, Chung WJ, Nam CM. Changes in mortality after the recent economic crisis in South Korea. Ann Epidemiol. 2004; 14(6):442–446. PMID: 15246334.28. Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017; 46(1):348–355. PMID: 27283160.29. Hendin H, Phillips M, Vijayakumar L, Pirkis J, Wang H, Yip P, et al. Suicide and Suicide Prevention in Asia. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2008.30. Mathers CD, Fat DM, Inoue M, Rao C, Lopez AD. Counting the dead and what they died from: an assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull World Health Organ. 2005; 83(3):171–177. PMID: 15798840.31. Kim MY, Lee SD. A proposal for writing a better death certificate. J Korean Med Assoc. 2018; 61(4):259–267.32. Jang JS, Jang SJ, Choi BH, Lee HY, Chung NE, Seo JS. A statistical analysis of legal autopsies performed in Korea in 2014. Korean J Leg Med. 2015; 39(4):99–108.33. An S, Lee H, Lee J, Kang S. Social stigma of suicide in South Korea: a cultural perspective. Death Stud. 2023; 47(3):259–267. PMID: 35332850.34. Lee SY. Life insurers pressured to pay suicide benefits. Korea Herald;Updated 2016. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20160622000935 .35. Oh S, Lee S. Historical changes of Korean death certificate form. Korean J Leg Med. 2019; 43(2):37–53.36. Huh CG, Nam K. A preview of tale of Korea’s two crises. Korea and the World Economy. 2010; 11:1–29.37. Ha J, Yang HS. The Werther effect of celebrity suicides: evidence from South Korea. PLoS One. 2021; 16(4):e0249896. PMID: 33909657.38. Kim JH, Park EC, Nam JM, Park S, Cho J, Kim SJ, et al. The Werther effect of two celebrity suicides: an entertainer and a politician. PLoS One. 2013; 8(12):e84876. PMID: 24386428.39. Lee AR. A study on policy alternatives for reducing deaths from suicide: a case study of Korean anti-suicide measures for 5 years. Korean J Policy Anal Eval. 2021; 31(2):117–144.40. Cha ES, Chang SS, Gunnell D, Eddleston M, Khang YH, Lee WJ. Impact of paraquat regulation on suicide in South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2016; 45(2):470–479. PMID: 26582846.41. Lee WJ, Cha ES. Overview of pesticide poisoning in South Korea. Journal of Rural Medicine. 2009; 4(2):53–58.42. Korea Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Suicides by decade. Updated 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://kfsp-datazoom.org/korea01.do .43. Ryu S, Nam HJ, Jhon M, Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim SW. Trends in suicide deaths before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. PLoS One. 2022; 17(9):e0273637. PMID: 36094911.44. Ha K. Can a Suicide Prevention Law decrease the suicide rate in Korea? J Korean Med Assoc. 2011; 54(8):792–794.45. Björkenstam C, Johansson LA, Nordström P, Thiblin I, Fugelstad A, Hallqvist J, et al. Suicide or undetermined intent? A register-based study of signs of misclassification. Popul Health Metr. 2014; 12(1):11. PMID: 24739594.46. Kapusta ND, Tran US, Rockett IR, De Leo D, Naylor CP, Niederkrotenthaler T, et al. Declining autopsy rates and suicide misclassification: a cross-national analysis of 35 countries. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(10):1050–1057. PMID: 21646567.47. Tøllefsen IM, Hem E, Ekeberg Ø. The reliability of suicide statistics: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2012; 12(1):9. PMID: 22333684.48. Matsubayashi T, Ueda M. Is suicide underreported? Evidence from Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022; 57(8):1571–1578. PMID: 34767033.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Practicability of Suicide Reduction Target in Korean Suicide Prevention Policy: Insights From Time Series Analysis

- Improving Causal Inference in Observational Studies: Interrupted Time Series Design

- Changes in Suicide Rate Trend After Implementation of Suicide Prevention Policy: An Interrupted Time Series Study on the Fifth Master Plan for Suicide Prevention

- Effects of a Province-Based Strategy to Prevent Suicide Using Charcoal Burning: A Preliminary Time Series Analysis

- Impact of the Early COVID-19 Pandemic on Suicide Attempts and Suicide Deaths in South Korea, 2016–2020: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis