Korean J Gastroenterol.

2024 Jan;83(1):28-32. 10.4166/kjg.2023.140.

Long-term Survivor of Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer Treated with Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology, Dankook University Hospital, Dankook University College of Medicine, Cheonan, Korea

- KMID: 2552240

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4166/kjg.2023.140

Abstract

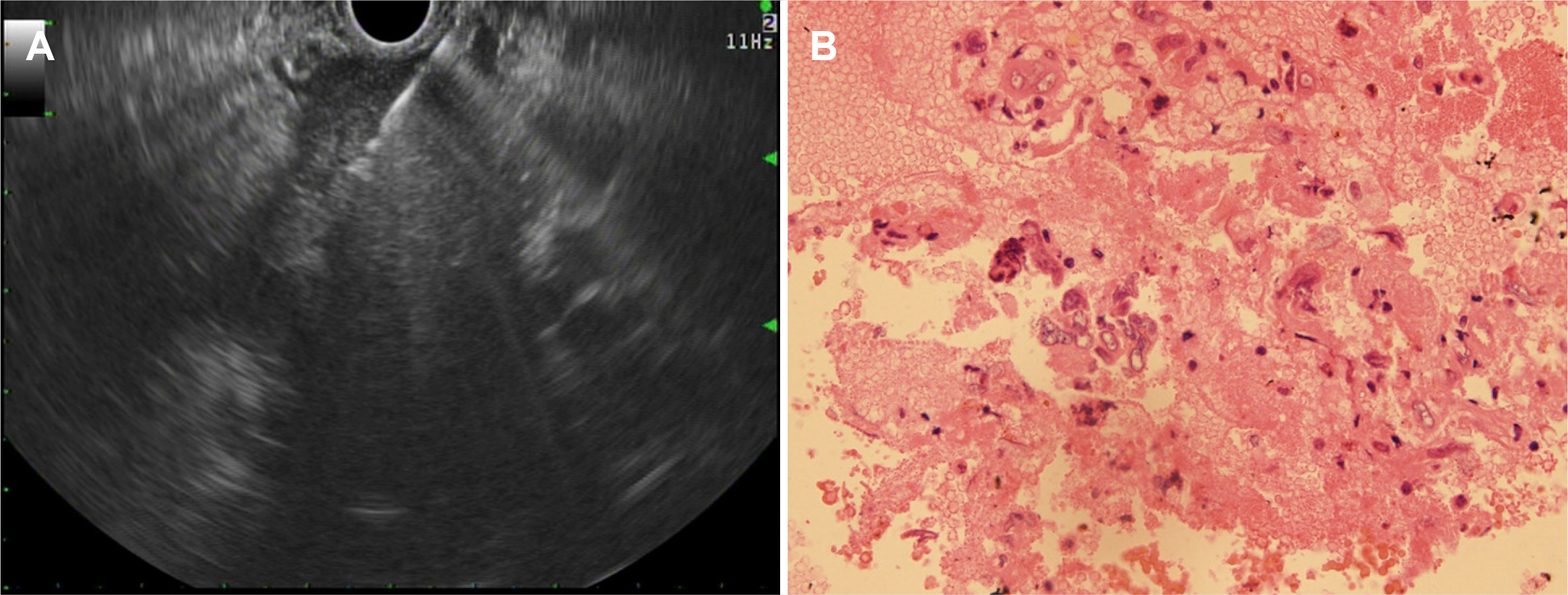

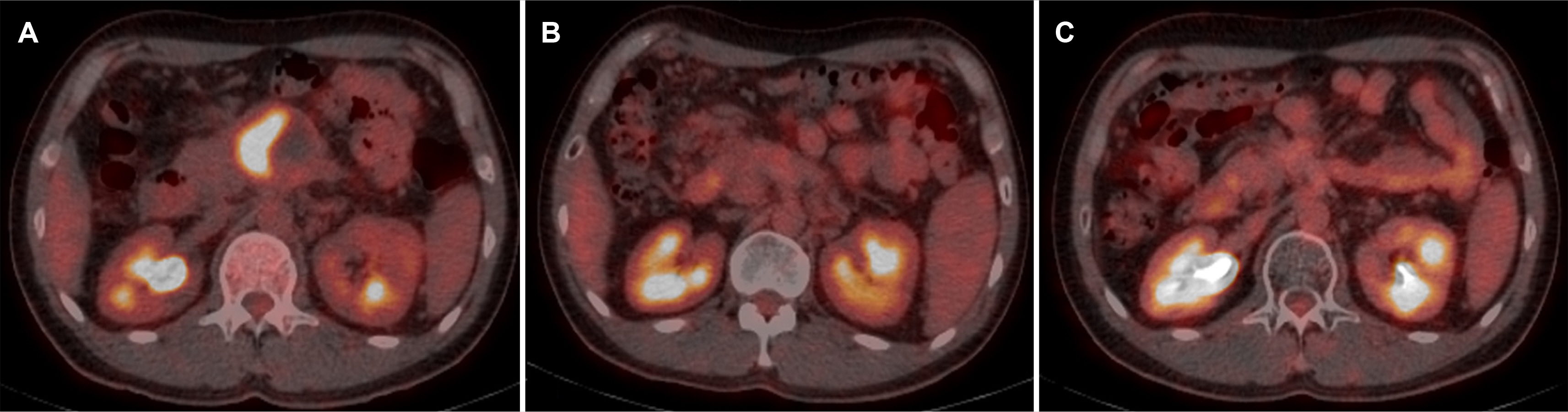

- differentiated carcinoma of the pancreas (UPC) is a rare, aggressive pancreatic cancer subtype. In addition, there is limited data on optimal management and patients tend to present with unresectable disease. This highlights the need to explore non-surgical treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In 2017, a 40-year-old male was diagnosed with UPC, presenting with a 6 cm mass in the pancreas, encasing the major arteries, indicative of a locally advanced stage. Histopathology confirmed UPC with osteoclast-like giant cells. After nine cycles of modified FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy and concurrent chemoradiotherapy, treatment was stopped in 2018 because of his declining health. Remarkably, despite the cessation of treatment, by 2023, the tumor had shrunk to 3.5 cm with no metabolic activity indicated by FDG-PET/CT. This six-year survival and response to non-surgical treatment highlight potential new avenues for managing unresectable pancreatic cancer, underscoring the need for further comprehensive studies to evaluate these therapeutic strategies.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Kardosh A, Lichtensztajn DY, Gubens MA, Kunz PL, Fisher GA, Clarke CA. 2018; Long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer: A California population-based study. Pancreas. 47:958–966. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001133. PMID: 30074526. PMCID: PMC6095724.2. Sirri E, Castro FA, Kieschke J, et al. 2016; Recent trends in survival of patients with pancreatic cancer in Germany and the United States. Pancreas. 45:908–914. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000588. PMID: 26745860.3. Bouvier AM, Bossard N, Colonna M, et al. 2017; Trends in net survival from pancreatic cancer in six European Latin countries: results from the SUDCAN population-based study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 26:S63–S69. DOI: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000303. PMID: 28005607.4. Manduch M, Dexter DF, Jalink DW, Vanner SJ, Hurlbut DJ. 2009; Undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells: report of a case with osteochondroid differentiation. Pathol Res Pract. 205:353–359. DOI: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.11.006. PMID: 19147301.5. Reid MD, Muraki T, HooKim K, et al. 2017; Cytologic features and clinical implications of undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells of the pancreas: An analysis of 15 cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 125:563–575. DOI: 10.1002/cncy.21859. PMID: 28371566.6. Muraki T, Reid MD, Basturk O, et al. 2016; Undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells of the pancreas: clinicopathologic analysis of 38 cases highlights a more protracted clinical course than currently appreciated. Am J Surg Pathol. 40:1203–1216. DOI: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000689. PMID: 27508975. PMCID: PMC4987218.7. Gao Y, Cai B, Yin L, et al. 2022; Undifferentiated carcinoma of pancreas with osteoclast-like giant cells: One Center's experience of 13 cases and characteristic pre-operative images. Cancer Manag Res. 14:1409–1419. DOI: 10.2147/CMAR.S349625. PMID: 35431580. PMCID: PMC9012233.8. Clark CJ, Graham RP, Arun JS, Harmsen WS, Reid-Lombardo KM. 2012; Clinical outcomes for anaplastic pancreatic cancer: a population-based study. J Am Coll Surg. 215:627–634. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.418. PMID: 23084492.9. Yoshioka M, Uchinami H, Watanabe G, et al. 2012; Effective use of gemcitabine in the treatment of undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells of the pancreas with portal vein tumor thrombus. Intern Med. 51:2145–2150. DOI: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7670. PMID: 22892493.10. Kobayashi S, Nakano H, Ooike N, Oohashi M, Koizumi S, Otsubo T. 2014; Long-term survivor of a resected undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells who underwent a second curative resection: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 8:1499–1504. DOI: 10.3892/ol.2014.2325. PMID: 25202356. PMCID: PMC4156164.11. Ueberroth BE, Liu AJ, Graham RP, et al. 2021; Osteoclast-like giant cell tumors of the pancreas: clinical characteristics, genetic testing, and treatment modalities. Pancreas. 50:952–956. DOI: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001858. PMID: 34369897.12. Temesgen WM, Wachtel M, Dissanaike S. 2014; Osteoclastic giant cell tumor of the pancreas. Int J Surg Case Rep. 5:175–179. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.01.002. PMID: 24631915. PMCID: PMC3980420.13. Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. 2009; DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 27:1806–1813. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7188. PMID: 19273710. PMCID: PMC2668706.14. Crane CH, Varadhachary GR, Yordy JS, et al. 2011; Phase II trial of cetuximab, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiation with cetuximab for locally advanced (T4) pancreatic adenocarcinoma: correlation of Smad4(Dpc4) immunostaining with pattern of disease progression. J Clin Oncol. 29:3037–3043. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8038. PMID: 21709185. PMCID: PMC3157965.15. Dong M, Nio Y, Tamura K, et al. 2000; Ki-ras point mutation and p53 expression in human pancreatic cancer: a comparative study among Chinese, Japanese, and Western patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 9:279–284.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Long Term Complete Response of Unresectable Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer after CCRT and Gemcitabine Chemotherapy

- Comparing Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy to Chemotherapy Alone for Locally Advanced Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer

- The Results of Radiotherapy in Locally Advanced, Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer

- Role of Neoadjuvant Therapy for Borderline Resectable or Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer

- Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone for Unresectable Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Retrospective Cohort Study