Intest Res.

2024 Jan;22(1):15-43. 10.5217/ir.2023.00080.

Gut microbiota in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapeutics of inflammatory bowel disease

- Affiliations

-

- 1Redcliffe Labs, Noida, India

- 2School of Biological Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

- 3Centre for Microbiome Medicine, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

- 4Department of Zoology, Ramjas College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India

- KMID: 2551277

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2023.00080

Abstract

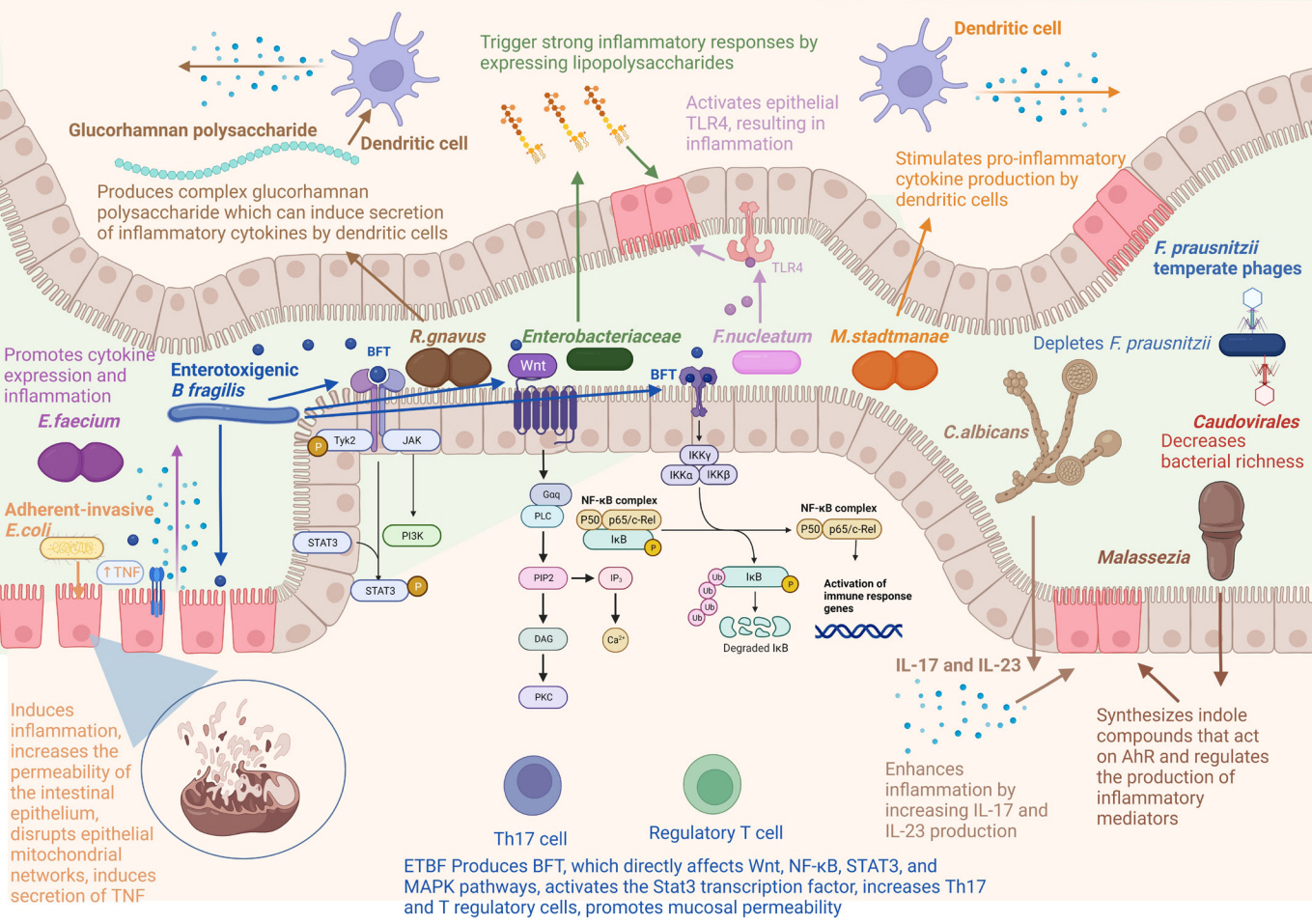

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a multifactorial disease, which is thought to be an interplay between genetic, environment, microbiota, and immune-mediated factors. Dysbiosis in the gut microbial composition, caused by antibiotics and diet, is closely related to the initiation and progression of IBD. Differences in gut microbiota composition between IBD patients and healthy individuals have been found, with reduced biodiversity of commensal microbes and colonization of opportunistic microbes in IBD patients. Gut microbiota can, therefore, potentially be used for diagnosing and prognosticating IBD, and predicting its treatment response. Currently, there are no curative therapies for IBD. Microbiota-based interventions, including probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation, have been recognized as promising therapeutic strategies. Clinical studies and studies done in animal models have provided sufficient evidence that microbiota-based interventions may improve inflammation, the remission rate, and microscopic aspects of IBD. Further studies are required to better understand the mechanisms of action of such interventions. This will help in enhancing their effectiveness and developing personalized therapies. The present review summarizes the relationship between gut microbiota and IBD immunopathogenesis. It also discusses the use of gut microbiota as a noninvasive biomarker and potential therapeutic option.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Borowitz SM. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: clues to pathogenesis? Front Pediatr. 2022; 10:1103713.

Article2. Kovarik JJ, Tillinger W, Hofer J, et al. Impaired anti-inflammatory efficacy of n-butyrate in patients with IBD. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011; 41:291–298.

Article3. Dmochowska N, Wardill HR, Hughes PA. Advances in imaging specific mediators of inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19:2471.

Article4. GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020; 5:17–30.5. Ramos GP, Papadakis KA. Mechanisms of disease: inflammatory bowel diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019; 94:155–165.

Article6. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017; 390:2769–2778.

Article7. Danese S, Malesci A, Vetrano S. Colitis-associated cancer: the dark side of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2011; 60:1609–1610.

Article8. Beaugerie L, Itzkowitz SH. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:1441–1452.

Article9. Loddo I, Romano C. Inflammatory bowel disease: genetics, epigenetics, and pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2015; 6:551.

Article10. Yamamoto M, Matsumoto S. Gut microbiota and colorectal cancer. Genes Environ. 2016; 38:11.

Article11. Canavan C, Abrams KR, Mayberry J. Meta-analysis: colorectal and small bowel cancer risk in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006; 23:1097–1104.

Article12. Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Mühlbauer M, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012; 338:120–123.

Article13. Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017; 389:1741–1755.

Article14. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017; 389:1756–1770.

Article15. Rowan-Nash AD, Korry BJ, Mylonakis E, Belenky P. Cross-domain and viral interactions in the microbiome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2019; 83:e00044–18.

Article16. Pandey H, Tang DW, Wong SH, Lal D. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer: biological role and therapeutic opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 2023; 15:866.

Article17. Bäckhed F. Programming of host metabolism by the gut microbiota. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011; 58 Suppl 2:44–52.

Article18. Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009; 9:313–323.

Article19. Sommer F, Anderson JM, Bharti R, Raes J, Rosenstiel P. The resilience of the intestinal microbiota influences health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017; 15:630–638.

Article20. Dethlefsen L, Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Relman DA. Assembly of the human intestinal microbiota. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006; 21:517–523.

Article21. Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008; 3:213–223.

Article22. Neish AS. Microbes in gastrointestinal health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009; 136:65–80.

Article23. Collado MC, Delgado S, Maldonado A, Rodríguez JM. Assessment of the bacterial diversity of breast milk of healthy women by quantitative real-time PCR. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009; 48:523–528.

Article24. Biasucci G, Rubini M, Riboni S, Morelli L, Bessi E, Retetangos C. Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the newborn gut. Early Hum Dev. 2010; 86 Suppl 1:13–15.

Article25. Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012; 486:222–227.

Article26. Faith JJ, Guruge JL, Charbonneau M, et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science. 2013; 341:1237439.

Article27. David LA, Materna AC, Friedman J, et al. Host lifestyle affects human microbiota on daily timescales. Genome Biol. 2014; 15:R89.

Article28. Rothschild D, Weissbrod O, Barkan E, et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature. 2018; 555:210–215.

Article29. Andoh A. Physiological role of gut microbiota for maintaining human health. Digestion. 2016; 93:176–181.

Article30. Nishida A, Inoue R, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Naito Y, Andoh A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018; 11:1–10.

Article31. Peterson DA, Frank DN, Pace NR, Gordon JI. Metagenomic approaches for defining the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Host Microbe. 2008; 3:417–427.

Article32. Li G, Yang M, Zhou K, et al. Diversity of duodenal and rectal microbiota in biopsy tissues and luminal contents in healthy volunteers. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015; 25:1136–1145.

Article33. Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017; 474:1823–1836.

Article34. Carstens A, Roos A, Andreasson A, et al. Differential clustering of fecal and mucosa-associated microbiota in ‘healthy’ individuals. J Dig Dis. 2018; 19:745–752.

Article35. Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Figueiredo C, Smet A, et al. Systematic review: gastric microbiota in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020; 51:582–602.

Article36. Corr SC, Hill C, Gahan CG. Understanding the mechanisms by which probiotics inhibit gastrointestinal pathogens. Adv Food Nutr Res. 2009; 56:1–15.37. Podolsky DK. The current future understanding of inflammatory bowel disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002; 16:933–943.

Article38. Swidsinski A, Ladhoff A, Pernthaler A, et al. Mucosal flora in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002; 122:44–54.

Article39. Andoh A, Kuzuoka H, Tsujikawa T, et al. Multicenter analysis of fecal microbiota profiles in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol. 2012; 47:1298–1307.

Article40. Kabeerdoss J, Jayakanthan P, Pugazhendhi S, Ramakrishna BS. Alterations of mucosal microbiota in the colon of patients with inflammatory bowel disease revealed by real time polymerase chain reaction amplification of 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid. Indian J Med Res. 2015; 142:23–32.

Article41. Stojanov S, Berlec A, Štrukelj B. The influence of probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in the treatment of obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms. 2020; 8:1715.

Article42. Kamada N, Seo SU, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013; 13:321–335.

Article43. Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014; 157:121–141.

Article44. Brown EM, Kenny DJ, Xavier RJ. Gut microbiota regulation of T cells during inflammation and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019; 37:599–624.

Article45. Ott SJ, Musfeldt M, Wenderoth DF, et al. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004; 53:685–693.

Article46. DeGruttola AK, Low D, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E. Current understanding of dysbiosis in disease in human and animal models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016; 22:1137–1150.

Article47. Singh VP, Proctor SD, Willing BP. Koch’s postulates, microbial dysbiosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016; 22:594–599.

Article48. Ni J, Wu GD, Albenberg L, Tomov VT. Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 14:573–584.

Article49. Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 3:390–407.

Article50. Bringiotti R, Ierardi E, Lovero R, Losurdo G, Di Leo A, Principi M. Intestinal microbiota: the explosive mixture at the origin of inflammatory bowel disease? World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014; 5:550–559.

Article51. Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet. 2015; 47:979–986.

Article52. Su HJ, Chiu YT, Chiu CT, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and its treatment in 2018: global and Taiwanese status updates. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019; 118:1083–1092.

Article53. Manichanh C, Borruel N, Casellas F, Guarner F. The gut microbiota in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 9:599–608.

Article54. Matsuoka K, Kanai T. The gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2015; 37:47–55.

Article55. Sokol H, Leducq V, Aschard H, et al. Fungal microbiota dysbiosis in IBD. Gut. 2017; 66:1039–1048.

Article56. Gophna U, Sommerfeld K, Gophna S, Doolittle WF, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ. Differences between tissue-associated intestinal microfloras of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006; 44:4136–4141.

Article57. Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104:13780–13785.

Article58. Xu J, Chen N, Wu Z, et al. 5-aminosalicylic acid alters the gut bacterial microbiota in patients with ulcerative colitis. Front Microbiol. 2018; 9:1274.

Article59. Zhou Y, Xu ZZ, He Y, et al. Gut microbiota offers universal biomarkers across ethnicity in inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis and infliximab response prediction. mSystems. 2018; 3:e00188–17.

Article60. Yu Y, Yang W, Li Y, Cong Y. Enteroendocrine cells: sensing gut microbiota and regulating inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020; 26:11–20.

Article61. Nemoto H, Kataoka K, Ishikawa H, et al. Reduced diversity and imbalance of fecal microbiota in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012; 57:2955–2964.

Article62. Fuentes S, Rossen NG, van der Spek MJ, et al. Microbial shifts and signatures of long-term remission in ulcerative colitis after faecal microbiota transplantation. ISME J. 2017; 11:1877–1889.

Article63. Khalil NA, Walton GE, Gibson GR, Tuohy KM, Andrews SC. In vitro batch cultures of gut microbiota from healthy and ulcerative colitis (UC) subjects suggest that sulphate-reducing bacteria levels are raised in UC and by a protein-rich diet. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2014; 65:79–88.

Article64. Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014; 15:382–392.

Article65. Zhu W, Winter MG, Byndloss MX, et al. Precision editing of the gut microbiota ameliorates colitis. Nature. 2018; 553:208–211.

Article66. Thomann AK, Mak JW, Zhang JW, et al. Review article: bugs, inflammation and mood-a microbiota-based approach to psychiatric symptoms in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020; 52:247–266.

Article67. Fujimoto T, Imaeda H, Takahashi K, et al. Decreased abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the gut microbiota of Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 28:613–619.

Article68. Takahashi K, Nishida A, Fujimoto T, et al. Reduced abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria species in the fecal microbial community in Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2016; 93:59–65.

Article69. Scanlan PD, Marchesi JR. Micro-eukaryotic diversity of the human distal gut microbiota: qualitative assessment using culture-dependent and -independent analysis of faeces. ISME J. 2008; 2:1183–1193.

Article70. Ghavami SB, Rostami E, Sephay AA, et al. Alterations of the human gut Methanobrevibacter smithii as a biomarker for inflammatory bowel diseases. Microb Pathog. 2018; 117:285–289.

Article71. Qiu X, Ma J, Jiao C, et al. Alterations in the mucosa-associated fungal microbiota in patients with ulcerative colitis. Oncotarget. 2017; 8:107577–107588.

Article72. Fernandes MA, Verstraete SG, Phan TG, et al. Enteric virome and bacterial microbiota in children with ulcerative colitis and crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019; 68:30–36.

Article73. Hoarau G, Mukherjee PK, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Bacteriome and mycobiome interactions underscore microbial dysbiosis in familial Crohn’s disease. mBio. 2016; 7:e01250–16.

Article74. Barnich N, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli and Crohn’s disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007; 23:16–20.

Article75. Mukhopadhya I, Hansen R, El-Omar EM, Hold GL. IBD: what role do Proteobacteria play? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 9:219–230.76. Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Cianci R, Bibbò S, Gasbarrini A, Currò D. The involvement of gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: potential for therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 149:191–212.

Article77. Palmela C, Chevarin C, Xu Z, et al. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2018; 67:574–587.

Article78. Barnich N, Carvalho FA, Glasser AL, et al. CEACAM6 acts as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli, supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2007; 117:1566–1574.

Article79. Ahmed I, Roy BC, Khan SA, Septer S, Umar S. Microbiome, metabolome and inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms. 2016; 4:20.

Article80. Mancini NL, Rajeev S, Jayme TS, et al. Crohn’s disease pathobiont adherent-invasive E. coli disrupts epithelial mitochondrial networks with implications for gut permeability. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 11:551–571.

Article81. Martinez-Medina M, Garcia-Gil LJ. Escherichia coli in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases: an update on adherent invasive Escherichia coli pathogenicity. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014; 5:213–227.

Article82. Chervy M, Barnich N, Denizot J. Adherent-invasive E. coli: update on the lifestyle of a troublemaker in Crohn’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21:3734.

Article83. Yasueda A, Mizushima T, Nezu R, et al. The effect of Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI on the prevention of pouchitis and alteration of the microbiota profile in patients with ulcerative colitis. Surg Today. 2016; 46:939–949.

Article84. Sears CL, Geis AL, Housseau F. Bacteroides fragilis subverts mucosal biology: from symbiont to colon carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2014; 124:4166–4172.

Article85. Lukiw WJ. Bacteroides fragilis lipopolysaccharide and inflammatory signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Microbiol. 2016; 7:1544.

Article86. Huang JY, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. The human commensal Bacteroides fragilis binds intestinal mucin. Anaerobe. 2011; 17:137–141.

Article87. Boleij A, Hechenbleikner EM, Goodwin AC, et al. The Bacteroides fragilis toxin gene is prevalent in the colon mucosa of colorectal cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60:208–215.

Article88. Sears CL. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis: a rogue among symbiotes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009; 22:349–369.

Article89. Zamani S, Hesam Shariati S, Zali MR, et al. Detection of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut Pathog. 2017; 9:53.

Article90. Tan H, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q, Chen W. Novel strains of Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides ovatus alleviate the LPS-induced inflammation in mice. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019; 103:2353–2365.

Article91. Wu S, Morin PJ, Maouyo D, Sears CL. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces c-Myc expression and cellular proliferation. Gastroenterology. 2003; 124:392–400.

Article92. Toprak NU, Yagci A, Gulluoglu BM, et al. A possible role of Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin in the aetiology of colorectal cancer. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006; 12:782–786.

Article93. Rabizadeh S, Rhee KJ, Wu S, et al. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis: a potential instigator of colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007; 13:1475–1483.

Article94. Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, et al. IL-6 and Stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009; 15:103–113.

Article95. Housseau F, Sears CL. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF)-mediated colitis in Min (Apc+/-) mice: a human commensal-based murine model of colon carcinogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010; 9:3–5.

Article96. Geis AL, Fan H, Wu X, et al. Regulatory T-cell response to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis colonization triggers IL17-dependent colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Discov. 2015; 5:1098–1109.

Article97. Chung L, Orberg ET, Geis AL, et al. Bacteroides fragilis toxin coordinates a pro-carcinogenic inflammatory cascade via targeting of colonic epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2018; 23:421.

Article98. Goodwin AC, Destefano Shields CE, et al. Polyamine catabolism contributes to enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-induced colon tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:15354–15359.

Article99. Kordahi MC, Stanaway IB, Avril M, et al. Genomic and functional characterization of a mucosal symbiont involved in early-stage colorectal cancer. Cell Host Microbe. 2021; 29:1589–1598.e6.

Article100. Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009; 461:1282–1286.

Article101. Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, et al. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science. 2011; 332:974–977.

Article102. Verma R, Verma AK, Ahuja V, Paul J. Real-time analysis of mucosal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2010; 48:4279–4282.

Article103. Hall AB, Yassour M, Sauk J, et al. A novel Ruminococcus gnavus clade enriched in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Genome Med. 2017; 9:103.

Article104. Henke MT, Kenny DJ, Cassilly CD, Vlamakis H, Xavier RJ, Clardy J. Ruminococcus gnavus, a member of the human gut microbiome associated with Crohn’s disease, produces an inflammatory polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019; 116:12672–12677.

Article105. Duncan SH, Hold GL, Harmsen HJ, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. Growth requirements and fermentation products of Fusobacterium prausnitzii, and a proposal to reclassify it as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii gen. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002; 52:2141–2146.

Article106. Mentella MC, Scaldaferri F, Pizzoferrato M, Gasbarrini A, Miggiano GA. Nutrition, IBD and gut microbiota: a review. Nutrients. 2020; 12:944.

Article107. Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105:16731–16736.

Article108. Vermeiren J, Van den Abbeele P, Laukens D, et al. Decreased colonization of fecal Clostridium coccoides/Eubacterium rectale species from ulcerative colitis patients in an in vitro dynamic gut model with mucin environment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012; 79:685–696.

Article109. Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014; 63:1275–1283.

Article110. Lopez-Siles M, Martinez-Medina M, Abellà C, et al. Mucosaassociated Faecalibacterium prausnitzii phylotype richness is reduced in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015; 81:7582–7592.

Article111. Quévrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2016; 65:415–425.

Article112. Heidarian F, Alebouyeh M, Shahrokh S, Balaii H, Zali MR. Altered fecal bacterial composition correlates with disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease and the extent of IL8 induction. Curr Res Transl Med. 2019; 67:41–50.

Article113. Lloyd-Price J, Arze C, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019; 569:655–662.

Article114. Pittayanon R, Lau JT, Leontiadis GI, et al. Differences in gut microbiota in patients with vs without inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:930–946. e1.

Article115. Varela E, Manichanh C, Gallart M, et al. Colonisation by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and maintenance of clinical remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 38:151–161.

Article116. Zhou L, Zhang M, Wang Y, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii produces butyrate to maintain Th17/Treg balance and to ameliorate colorectal colitis by inhibiting histone deacetylase 1. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018; 24:1926–1940.

Article117. Imhann F, Vich Vila A, Bonder MJ, et al. Interplay of host genetics and gut microbiota underlying the onset and clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2018; 67:108–119.

Article118. Vich Vila A, Imhann F, Collij V, et al. Gut microbiota composition and functional changes in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Transl Med. 2018; 10:eaap8914.

Article119. Franzosa EA, Sirota-Madi A, Avila-Pacheco J, et al. Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol. 2019; 4:293–305.

Article120. Ryz NR, Patterson SJ, Zhang Y, et al. Active vitamin D (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) increases host susceptibility to Citrobacter rodentium by suppressing mucosal Th17 responses. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012; 303:G1299–G1311.121. Nazareth N, Magro F, Machado E, et al. Prevalence of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis and Escherichia coli in blood samples from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015; 204:681–692.

Article122. Seishima J, Iida N, Kitamura K, et al. Gut-derived Enterococcus faecium from ulcerative colitis patients promotes colitis in a genetically susceptible mouse host. Genome Biol. 2019; 20:252.

Article123. Ohkusa T, Yoshida T, Sato N, Watanabe S, Tajiri H, Okayasu I. Commensal bacteria can enter colonic epithelial cells and induce proinflammatory cytokine secretion: a possible pathogenic mechanism of ulcerative colitis. J Med Microbiol. 2009; 58:535–545.

Article124. Bashir A, Miskeen AY, Hazari YM, Asrafuzzaman S, Fazili KM. Fusobacterium nucleatum, inflammation, and immunity: the fire within human gut. Tumour Biol. 2016; 37:2805–2810.

Article125. Engevik M, Danhof H, Britton R, Versalovic J. Elucidating the role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in intestinal inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020; 26:S29.126. Lurie-Weinberger MN, Gophna U. Archaea in and on the human body: health implications and future directions. PLoS Pathog. 2015; 11:e1004833.

Article127. Nkamga VD, Henrissat B, Drancourt M. Archaea: essential inhabitants of the human digestive microbiota. Human Microbiome J. 2017; 3:1–8.

Article128. Pausan MR, Csorba C, Singer G, et al. Exploring the archaeome: detection of archaeal signatures in the human body. Front Microbiol. 2019; 10:2796.

Article129. Kim JY, Whon TW, Lim MY, et al. The human gut archaeome: identification of diverse haloarchaea in Korean subjects. Microbiome. 2020; 8:114.

Article130. Samuel BS, Gordon JI. A humanized gnotobiotic mouse model of host-archaeal-bacterial mutualism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103:10011–10016.

Article131. Blais Lecours P, Marsolais D, Cormier Y, et al. Increased prevalence of Methanosphaera stadtmanae in inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e87734.

Article132. Bang C, Weidenbach K, Gutsmann T, Heine H, Schmitz RA. The intestinal archaea Methanosphaera stadtmanae and Methanobrevibacter smithii activate human dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e99411.

Article133. Oxley AP, Lanfranconi MP, Würdemann D, et al. Halophilic archaea in the human intestinal mucosa. Environ Microbiol. 2010; 12:2398–2410.

Article134. Chehoud C, Albenberg LG, Judge C, et al. Fungal signature in the gut microbiota of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015; 21:1948–1956.

Article135. Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010; 464:59–65.136. Lewis JD, Chen EZ, Baldassano RN, et al. Inflammation, antibiotics, and diet as environmental stressors of the gut microbiome in pediatric Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2015; 18:489–500.

Article137. Hallen-Adams HE, Suhr MJ. Fungi in the healthy human gastrointestinal tract. Virulence. 2017; 8:352–358.

Article138. Jones L, Kumar J, Mistry A, et al. The transformative possibilities of the microbiota and mycobiota for health, disease, aging, and technological innovation. Biomedicines. 2019; 7:24.

Article139. Liguori G, Lamas B, Richard ML, et al. Fungal dysbiosis in mucosa-associated microbiota of Crohn’s disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10:296–305.

Article140. Lam S, Zuo T, Ho M, Chan FK, Chan PK, Ng SC. Review article: fungal alterations in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019; 50:1159–1171.

Article141. Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science. 2012; 336:1314–1317.

Article142. Wang T, Pan D, Zhou Z, et al. Dectin-3 deficiency promotes colitis development due to impaired antifungal innate immune responses in the gut. PLoS Pathog. 2016; 12:e1005662.

Article143. Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, et al. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol. 2007; 37:2695–2706.

Article144. Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009; 206:299–311.

Article145. Saunus JM, Wagner SA, Matias MA, Hu Y, Zaini ZM, Farah CS. Early activation of the interleukin-23-17 axis in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2010; 25:343–356.

Article146. Tiago FC, Porto BA, Ribeiro NS, et al. Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain UFMG A-905 in experimental model of inflammatory bowel disease. Benef Microbes. 2015; 6:807–815.

Article147. Pericolini E, Gabrielli E, Ballet N, et al. Therapeutic activity of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based probiotic and inactivated whole yeast on vaginal candidiasis. Virulence. 2017; 8:74–90.

Article148. Guslandi M, Giollo P, Testoni PA. A pilot trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003; 15:697–698.

Article149. Thomas S, Metzke D, Schmitz J, Dörffel Y, Baumgart DC. Anti-inflammatory effects of Saccharomyces boulardii mediated by myeloid dendritic cells from patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011; 301:G1083–G1092.

Article150. Kellermayer R, Mir SA, Nagy-Szakal D, et al. Microbiota separation and C-reactive protein elevation in treatment-naïve pediatric granulomatous Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012; 55:243–250.

Article151. Limon JJ, Tang J, Li D, et al. Malassezia is associated with Crohn’s disease and exacerbates colitis in mouse models. Cell Host Microbe. 2019; 25:377–388.e6.

Article152. Magiatis P, Pappas P, Gaitanis G, et al. Malassezia yeasts produce a collection of exceptionally potent activators of the Ah (dioxin) receptor detected in diseased human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2013; 133:2023–2030.

Article153. Wheeler ML, Limon JJ, Underhill DM. Immunity to commensal fungi: detente and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017; 12:359–385.

Article154. Spatz M, Richard ML. Overview of the potential role of Malassezia in gut health and disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020; 10:201.

Article155. Swanson HI. Cytochrome P450 expression in human keratinocytes: an aryl hydrocarbon receptor perspective. Chem Biol Interact. 2004; 149:69–79.

Article156. Minot S, Bryson A, Chehoud C, Wu GD, Lewis JD, Bushman FD. Rapid evolution of the human gut virome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110:12450–12455.

Article157. Shkoporov AN, Clooney AG, Sutton TD, et al. The human gut virome is highly diverse, stable, and individual specific. Cell Host Microbe. 2019; 26:527–541.

Article158. Ungaro F, Massimino L, D’Alessio S, Danese S. The gut virome in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: from metagenomics to novel therapeutic approaches. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019; 7:999–1007.

Article159. Zuo T, Lu XJ, Zhang Y, et al. Gut mucosal virome alterations in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2019; 68:1169–1179.

Article160. Clooney AG, Sutton TD, Shkoporov AN, et al. Whole-virome analysis sheds light on viral dark matter in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2019; 26:764–778.

Article161. Waller AS, Yamada T, Kristensen DM, et al. Classification and quantification of bacteriophage taxa in human gut metagenomes. ISME J. 2014; 8:1391–1402.

Article162. Norman JM, Handley SA, Baldridge MT, et al. Disease-specific alterations in the enteric virome in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2015; 160:447–460.

Article163. Pérez-Brocal V, García-López R, Vázquez-Castellanos JF, et al. Study of the viral and microbial communities associated with Crohn’s disease: a metagenomic approach. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2013; 4:e36.

Article164. Wang W, Jovel J, Halloran B, et al. Metagenomic analysis of microbiome in colon tissue from subjects with inflammatory bowel diseases reveals interplay of viruses and bacteria. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015; 21:1419–1427.

Article165. Duerkop BA, Kleiner M, Paez-Espino D, et al. Murine colitis reveals a disease-associated bacteriophage community. Nat Microbiol. 2018; 3:1023–1031.

Article166. Seth RK, Maqsood R, Mondal A, et al. Gut DNA virome diversity and its association with host bacteria regulate inflammatory phenotype and neuronal immunotoxicity in experimental gulf war illness. Viruses. 2019; 11:968.

Article167. Gogokhia L, Buhrke K, Bell R, et al. Expansion of bacteriophages is linked to aggravated intestinal inflammation and colitis. Cell Host Microbe. 2019; 25:285–299.

Article168. Pérez-Brocal V, García-López R, Nos P, Beltrán B, Moret I, Moya A. Metagenomic analysis of Crohn’s disease patients identifies changes in the virome and microbiome related to disease status and therapy, and detects potential interactions and biomarkers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015; 21:2515–2532.

Article169. Cornuault JK, Petit MA, Mariadassou M, et al. Phages infecting Faecalibacterium prausnitzii belong to novel viral genera that help to decipher intestinal viromes. Microbiome. 2018; 6:65.

Article170. Galtier M, De Sordi L, Sivignon A, et al. bacteriophages targeting adherent invasive Escherichia coli strains as a promising new treatment for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017; 11:840–847.171. Yang JY, Kim MS, Kim E, et al. Enteric viruses ameliorate gut inflammation via toll-like receptor 3 and toll-like receptor 7-mediated interferon-β production. Immunity. 2016; 44:889–900.

Article172. Virgin HW. The virome in mammalian physiology and disease. Cell. 2014; 157:142–150.

Article173. Ungaro F, Massimino L, Furfaro F, et al. Metagenomic analysis of intestinal mucosa revealed a specific eukaryotic gut virome signature in early-diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease. Gut Microbes. 2019; 10:149–158.174. Cadwell K, Patel KK, Maloney NS, et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn’s disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell. 2010; 141:1135–1145.

Article175. Bolsega S, Basic M, Smoczek A, et al. Composition of the intestinal microbiota determines the outcome of virus-triggered colitis in mice. Front Immunol. 2019; 10:1708.

Article176. Ananthakrishnan AN, Luo C, Yajnik V, et al. Gut microbiome function predicts response to anti-integrin biologic therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Cell Host Microbe. 2017; 21:603–610.

Article177. Lopez-Siles M, Martinez-Medina M, Busquets D, et al. Mucosa-associated Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Escherichia coli co-abundance can distinguish irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Int J Med Microbiol. 2014; 304:464–475.

Article178. Prosberg M, Bendtsen F, Vind I, Petersen AM, Gluud LL. The association between the gut microbiota and the inflammatory bowel disease activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016; 51:1407–1415.

Article179. Duranti S, Gaiani F, Mancabelli L, et al. Elucidating the gut microbiome of ulcerative colitis: bifidobacteria as novel microbial biomarkers. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016; 92:fiw191.

Article180. Gong D, Gong X, Wang L, Yu X, Dong Q. Involvement of reduced microbial diversity in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016; 2016:6951091.

Article181. Sartor RB, Wu GD. Roles for intestinal bacteria, viruses, and fungi in pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases and therapeutic approaches. Gastroenterology. 2017; 152:327–339.

Article182. Dong LN, Wang M, Guo J, Wang JP. Role of intestinal microbiota and metabolites in inflammatory bowel disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019; 132:1610–1614.

Article183. Wang W, Chen L, Zhou R, et al. Increased proportions of Bifidobacterium and the Lactobacillus group and loss of butyrate-producing bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2014; 52:398–406.

Article184. Nishino K, Nishida A, Inoue R, et al. Analysis of endoscopic brush samples identified mucosa-associated dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018; 53:95–106.

Article185. Fukuda K, Fujita Y. Determination of the discriminant score of intestinal microbiota as a biomarker of disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014; 14:49.

Article186. He XX, Li YH, Yan PG, et al. Relationship between clinical features and intestinal microbiota in Chinese patients with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021; 27:4722–4737.

Article187. Pascal V, Pozuelo M, Borruel N, et al. A microbial signature for Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017; 66:813–822.

Article188. Le Gall G, Noor SO, Ridgway K, et al. Metabolomics of fecal extracts detects altered metabolic activity of gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. J Proteome Res. 2011; 10:4208–4218.

Article189. De Preter V, Machiels K, Joossens M, et al. Faecal metabolite profiling identifies medium-chain fatty acids as discriminating compounds in IBD. Gut. 2015; 64:447–458.

Article190. Santoru ML, Piras C, Murgia A, et al. Cross sectional evaluation of the gut-microbiome metabolome axis in an Italian cohort of IBD patients. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:9523.

Article191. Marchesi JR, Holmes E, Khan F, et al. Rapid and noninvasive metabonomic characterization of inflammatory bowel disease. J Proteome Res. 2007; 6:546–551.

Article192. Bjerrum JT, Wang Y, Hao F, et al. Metabonomics of human fecal extracts characterize ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease and healthy individuals. Metabolomics. 2015; 11:122–133.

Article193. Jacobs JP, Goudarzi M, Singh N, et al. A disease-associated microbial and metabolomics state in relatives of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 2:750–766.

Article194. Kolho KL, Pessia A, Jaakkola T, de Vos WM, Velagapudi V. Faecal and serum metabolomics in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017; 11:321–334.

Article195. Ooi M, Nishiumi S, Yoshie T, et al. GC/MS-based profiling of amino acids and TCA cycle-related molecules in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Res. 2011; 60:831–840.

Article196. Stephens NS, Siffledeen J, Su X, Murdoch TB, Fedorak RN, Slupsky CM. Urinary NMR metabolomic profiles discriminate inflammatory bowel disease from healthy. J Crohns Colitis. 2013; 7:e42–e48.

Article197. Williams HR, Cox IJ, Walker DG, et al. Differences in gut microbial metabolism are responsible for reduced hippurate synthesis in Crohn’s disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010; 10:108.

Article198. Hisamatsu T, Okamoto S, Hashimoto M, et al. Novel, objective, multivariate biomarkers composed of plasma amino acid profiles for the diagnosis and assessment of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e31131.

Article199. Postler TS, Ghosh S. Understanding the holobiont: how microbial metabolites affect human health and shape the immune system. Cell Metab. 2017; 26:110–130.

Article200. Morgan XC, Tickle TL, Sokol H, et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol. 2012; 13:R79.

Article201. Louis P, Hold GL, Flint HJ. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014; 12:661–672.

Article202. Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 16:461–478.

Article203. Liu P, Wang Y, Yang G, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in intestinal barrier function, inflammation, oxidative stress, and colonic carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Res. 2021; 165:105420.

Article204. Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, Duncan SH. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 9:577–589.

Article205. Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2017; 19:29–41.

Article206. Jang YS, Im JA, Choi SY, Lee JI, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Clostridium acetobutylicum for butyric acid production with high butyric acid selectivity. Metab Eng. 2014; 23:165–174.

Article207. Deleu S, Machiels K, Raes J, Verbeke K, Vermeire S. Short chain fatty acids and its producing organisms: an overlooked therapy for IBD? EBioMedicine. 2021; 66:103293.

Article208. Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013; 341:569–573.

Article209. Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111:2247–2252.

Article210. Krautkramer KA, Kreznar JH, Romano KA, et al. Diet-microbiota interactions mediate global epigenetic programming in multiple host tissues. Mol Cell. 2016; 64:982–992.

Article211. Hinnebusch BF, Meng S, Wu JT, Archer SY, Hodin RA. The effects of short-chain fatty acids on human colon cancer cell phenotype are associated with histone hyperacetylation. J Nutr. 2002; 132:1012–1017.

Article212. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbederived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013; 504:446–450.

Article213. Takaishi H, Matsuki T, Nakazawa A, et al. Imbalance in intestinal microflora constitution could be involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008; 298:463–472.

Article214. Huda-Faujan N, Abdulamir AS, Fatimah AB, et al. The impact of the level of the intestinal short chain fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease patients versus healthy subjects. Open Biochem J. 2010; 4:53–58.

Article215. Facchin S, Vitulo N, Calgaro M, et al. Microbiota changes induced by microencapsulated sodium butyrate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020; 32:e13914.

Article216. Vernia P, Gnaedinger A, Hauck W, Breuer RI. Organic anions and the diarrhea of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988; 33:1353–1358.

Article217. Hove H, Mortensen PB. Influence of intestinal inflammation (IBD) and small and large bowel length on fecal short-chain fatty acids and lactate. Dig Dis Sci. 1995; 40:1372–1380.

Article218. Ang Z, Ding JL. GPR41 and GPR43 in obesity and inflammation:protective or causative? Front Immunol. 2016; 7:28.

Article219. Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278:11312–11319.

Article220. Thangaraju M, Cresci GA, Liu K, et al. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009; 69:2826–2832.

Article221. Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, et al. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014; 40:128–139.

Article222. Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013; 504:451–455.

Article223. Sun M, Wu W, Liu Z, Cong Y. Microbiota metabolite short chain fatty acids, GPCR, and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2017; 52:1–8.

Article224. Zhao Y, Chen F, Wu W, et al. GPR43 mediates microbiota metabolite SCFA regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression in intestinal epithelial cells via activation of mTOR and STAT3. Mucosal Immunol. 2018; 11:752–762.

Article225. Tominaga K, Tsuchiya A, Mizusawa T, et al. Evaluation of intestinal microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, and immunoglobulin a in diversion colitis. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2021; 25:100892.

Article226. Macia L, Tan J, Vieira AT, et al. Metabolite-sensing receptors GPR43 and GPR109A facilitate dietary fibre-induced gut homeostasis through regulation of the inflammasome. Nat Commun. 2015; 6:6734.

Article227. Usami M, Kishimoto K, Ohata A, et al. Butyrate and trichostatin A attenuate nuclear factor kappaB activation and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion and increase prostaglandin E2 secretion in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Nutr Res. 2008; 28:321–328.

Article228. Davie JR. Inhibition of histone deacetylase activity by butyrate. J Nutr. 2003; 133:2485S–2493S.

Article229. Kaiko GE, Ryu SH, Koues OI, et al. The colonic crypt protects stem cells from microbiota-derived metabolites. Cell. 2016; 165:1708–1720.

Article230. Sartor RB. Gut microbiota: diet promotes dysbiosis and colitis in susceptible hosts. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 9:561–562.

Article231. El Kaoutari A, Armougom F, Gordon JI, Raoult D, Henrissat B. The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013; 11:497–504.

Article232. Daïen CI, Pinget GV, Tan JK, Macia L. Detrimental impact of microbiota-accessible carbohydrate-deprived diet on gut and immune homeostasis: an overview. Front Immunol. 2017; 8:548.

Article233. Tingirikari JM. Microbiota-accessible pectic poly- and oligosaccharides in gut health. Food Funct. 2018; 9:5059–5073.

Article234. Kelly CJ, Zheng L, Campbell EL, et al. Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host Microbe. 2015; 17:662–671.

Article235. Vernia P, Marcheggiano A, Caprilli R, et al. Short-chain fatty acid topical treatment in distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995; 9:309–313.

Article236. Garner CE, Smith S, de Lacy Costello B, et al. Volatile organic compounds from feces and their potential for diagnosis of gastrointestinal disease. FASEB J. 2007; 21:1675–1688.

Article237. Mañé J, Pedrosa E, Lorén V, et al. Partial replacement of dietary (n-6) fatty acids with medium-chain triglycerides decreases the incidence of spontaneous colitis in interleukin-10-deficient mice. J Nutr. 2009; 139:603–610.

Article238. Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB, Bajaj JS. Bile acids and the gut microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014; 30:332–338.

Article239. Quinn RA, Melnik AV, Vrbanac A, et al. Global chemical effects of the microbiome include new bile-acid conjugations. Nature. 2020; 579:123–129.

Article240. Wang YD, Chen WD, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W. The G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor, Gpbar1 (TGR5), negatively regulates hepatic inflammatory response through antagonizing nuclear factor κ light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) in mice. Hepatology. 2011; 54:1421–1432.

Article241. Jones BV, Begley M, Hill C, Gahan CG, Marchesi JR. Functional and comparative metagenomic analysis of bile salt hydrolase activity in the human gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105:13580–13585.

Article242. Labbé A, Ganopolsky JG, Martoni CJ, Prakash S, Jones ML. Bacterial bile metabolising gene abundance in Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis and type 2 diabetes metagenomes. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e115175.

Article243. Kurdi P, Kawanishi K, Mizutani K, Yokota A. Mechanism of growth inhibition by free bile acids in lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2006; 188:1979–1986.

Article244. Inagaki T, Moschetta A, Lee YK, et al. Regulation of antibacterial defense in the small intestine by the nuclear bile acid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006; 103:3920–3925.

Article245. Termén S, Tollin M, Rodriguez E, et al. PU.1 and bacterial metabolites regulate the human gene CAMP encoding antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in colon epithelial cells. Mol Immunol. 2008; 45:3947–3955.

Article246. D’Aldebert E, Biyeyeme Bi Mve MJ, Mergey M, et al. Bile salts control the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin through nuclear receptors in the human biliary epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2009; 136:1435–1443.

Article247. Song X, Sun X, Oh SF, et al. Microbial bile acid metabolites modulate gut RORγ+ regulatory T cell homeostasis. Nature. 2020; 577:410–415.

Article248. Jansson J, Willing B, Lucio M, et al. Metabolomics reveals metabolic biomarkers of Crohn’s disease. PLoS One. 2009; 4:e6386.

Article249. Torres J, Palmela C, Brito H, et al. The gut microbiota, bile acids and their correlation in primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018; 6:112–122.

Article250. Sinha SR, Haileselassie Y, Nguyen LP, et al. Dysbiosis-induced secondary bile acid deficiency promotes intestinal inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2020; 27:659–670.

Article251. Sun L, Cai J, Gonzalez FJ. The role of farnesoid X receptor in metabolic diseases, and gastrointestinal and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 18:335–347.

Article252. Vavassori P, Mencarelli A, Renga B, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S. The bile acid receptor FXR is a modulator of intestinal innate immunity. J Immunol. 2009; 183:6251–6261.

Article253. Gadaleta RM, van Erpecum KJ, Oldenburg B, et al. Farnesoid X receptor activation inhibits inflammation and preserves the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2011; 60:463–472.

Article254. Wilson A, Almousa A, Teft WA, Kim RB. Attenuation of bile acid-mediated FXR and PXR activation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Sci Rep. 2020; 10:1866.

Article255. Nikolaus S, Schulte B, Al-Massad N, et al. Increased tryptophan metabolism is associated with activity of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017; 153:1504–1516.256. Cervenka I, Agudelo LZ, Ruas JL. Kynurenines: tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science. 2017; 357:eaaf9794.

Article257. Zenewicz LA, Yancopoulos GD, Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Stevens S, Flavell RA. Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity. 2008; 29:947–957.

Article258. Venkatesh M, Mukherjee S, Wang H, et al. Symbiotic bacterial metabolites regulate gastrointestinal barrier function via the xenobiotic sensor PXR and Toll-like receptor 4. Immunity. 2014; 41:296–310.

Article259. Agus A, Planchais J, Sokol H. Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2018; 23:716–724.

Article260. Roager HM, Licht TR. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat Commun. 2018; 9:3294.

Article261. Li X, Zhang ZH, Zabed HM, Yun J, Zhang G, Qi X. An insight into the roles of dietary tryptophan and its metabolites in intestinal inflammation and inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2021; 65:e2000461.

Article262. Monteleone I, Rizzo A, Sarra M, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-induced signals up-regulate IL-22 production and inhibit inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 2011; 141:237–248.

Article263. Takamura T, Harama D, Fukumoto S, et al. Lactobacillus bulgaricus OLL1181 activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway and inhibits colitis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011; 89:817–822.

Article264. Ga1rg A, Zhao A, Erickson SL, et al. Pregnane X receptor activation attenuates inflammation-associated intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by inhibiting cytokine-induced myosin light-chain kinase expression and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1/2 activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016; 359:91–101.

Article265. Alexeev EE, Lanis JM, Kao DJ, et al. Microbiota-derived indole metabolites promote human and murine intestinal homeostasis through regulation of interleukin-10 receptor. Am J Pathol. 2018; 188:1183–1194.

Article266. Wlodarska M, Luo C, Kolde R, et al. Indoleacrylic acid produced by commensal peptostreptococcus species suppresses inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2017; 22:25–37.

Article267. Hashimoto T, Perlot T, Rehman A, et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012; 487:477–481.

Article268. De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Zitoun C, Duchampt A, Bäckhed F, Mithieux G. Microbiota-produced succinate improves glucose homeostasis via intestinal gluconeogenesis. Cell Metab. 2016; 24:151–157.

Article269. Mills EL, Kelly B, Logan A, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase supports metabolic repurposing of mitochondria to drive inflammatory macrophages. Cell. 2016; 167:457–470.

Article270. Macias-Ceja DC, Ortiz-Masiá D, Salvador P, et al. Succinate receptor mediates intestinal inflammation and fibrosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019; 12:178–187.

Article271. Casén C, Vebø HC, Sekelja M, et al. Deviations in human gut microbiota: a novel diagnostic test for determining dysbiosis in patients with IBS or IBD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 42:71–83.

Article272. Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota: a systematic review. J Infect. 2019; 79:471–489.

Article273. Hazel K, O’Connor A. Emerging treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020; 11:2040622319899297.

Article274. Hoffmann TW, Pham HP, Bridonneau C, et al. Microorganisms linked to inflammatory bowel disease-associated dysbiosis differentially impact host physiology in gnotobiotic mice. ISME J. 2016; 10:460–477.

Article275. Kamarlı Altun H, Akal Yıldız E, Akın M. Effects of synbiotic therapy in mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019; 30:313–320.

Article276. Amoroso C, Perillo F, Strati F, Fantini MC, Caprioli F, Facciotti F. The role of gut microbiota biomodulators on mucosal immunity and intestinal inflammation. Cells. 2020; 9:1234.

Article277. Naseer M, Poola S, Ali S, Samiullah S, Tahan V. Prebiotics and probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: where are we now and where are we going? Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2020; 15:216–233.

Article278. Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, et al. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 11:506–514.

Article279. Neish AS, Gewirtz AT, Zeng H, et al. Prokaryotic regulation of epithelial responses by inhibition of IkappaB-alpha ubiquitination. Science. 2000; 289:1560–1563.

Article280. Kamada N, Kim YG, Sham HP, et al. Regulated virulence controls the ability of a pathogen to compete with the gut microbiota. Science. 2012; 336:1325–1329.

Article281. Balakrishnan M, Floch MH. Prebiotics, probiotics and digestive health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012; 15:580–585.

Article282. Mackowiak PA. Recycling Metchnikoff: probiotics, the intestinal microbiome and the quest for long life. Front Public Health. 2013; 1:52.

Article283. Tojo R, Suárez A, Clemente MG, et al. Intestinal microbiota in health and disease: role of bifidobacteria in gut homeostasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014; 20:15163–15176.

Article284. Mills JP, Rao K, Young VB. Probiotics for prevention of Clostridium difficile infection. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018; 34:3–10.

Article285. Piewngam P, Zheng Y, Nguyen TH, et al. Pathogen elimination by probiotic Bacillus via signalling interference. Nature. 2018; 562:532–537.

Article286. Raman M, Ambalam P, Kondepudi KK, et al. Potential of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics for management of colorectal cancer. Gut Microbes. 2013; 4:181–192.

Article287. Saber R, Zadeh M, Pakanati KC, Bere P, Klaenhammer T, Mohamadzadeh M. Lipoteichoic acid-deficient Lactobacillus acidophilus regulates downstream signals. Immunotherapy. 2011; 3:337–347.

Article288. Tamaki H, Nakase H, Inoue S, et al. Efficacy of probiotic treatment with Bifidobacterium longum 536 for induction of remission in active ulcerative colitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Dig Endosc. 2016; 28:67–74.

Article289. Xia Y, Chen Y, Wang G, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum AR113 alleviates DSS-induced colitis by regulating the TLR4/MyD88/NF-kB pathway and gut microbiota composition. J Funct Foods. 2020; 67:103854.290. Fedorak RN, Feagan BG, Hotte N, et al. The probiotic VSL#3 has anti-inflammatory effects and could reduce endoscopic recurrence after surgery for Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 13:928–935.

Article291. O’Toole PW, Marchesi JR, Hill C. Next-generation probiotics: the spectrum from probiotics to live biotherapeutics. Nat Microbiol. 2017; 2:17057.

Article292. Hayashi A, Sato T, Kamada N, et al. A single strain of Clostridium butyricum induces intestinal IL-10-producing macrophages to suppress acute experimental colitis in mice. Cell Host Microbe. 2013; 13:711–722.

Article293. Yoshimatsu Y, Yamada A, Furukawa R, et al. Effectiveness of probiotic therapy for the prevention of relapse in patients with inactive ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015; 21:5985–5994.

Article294. Kruis W, Schütz E, Fric P, Fixa B, Judmaier G, Stolte M. Double-blind comparison of an oral Escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997; 11:853–858.

Article295. Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J, et al. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut. 2004; 53:1617–1623.

Article296. Shanahan F, Collins SM. Pharmabiotic manipulation of the microbiota in gastrointestinal disorders, from rationale to reality. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39:721–726.

Article297. Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017; 11:769–784.

Article298. Oliva S, Di Nardo G, Ferrari F, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the effectiveness of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 rectal enema in children with active distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012; 35:327–334.

Article299. Jin J, Wu S, Xie Y, Liu H, Gao X, Zhang H. Live and heat-killed cells of Lactobacillus plantarum Zhang-LL ease symptoms of chronic ulcerative colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium in rats. J Funct Foods. 2020; 71:103994.

Article300. Cheng FS, Pan D, Chang B, Jiang M, Sang LX. Probiotic mixture VSL#3: an overview of basic and clinical studies in chronic diseases. World J Clin Cases. 2020; 8:1361–1384.

Article301. Sood A, Midha V, Makharia GK, et al. The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 7:1202–1209.

Article302. Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Papa A, et al. Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:2218–2227.303. Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, et al. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000; 119:305–309.

Article304. Shen J, Zuo ZX, Mao AP. Effect of probiotics on inducing remission and maintaining therapy in ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and pouchitis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014; 20:21–35.

Article305. Pagnini C, Saeed R, Bamias G, Arseneau KO, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F. Probiotics promote gut health through stimulation of epithelial innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:454–459.

Article306. Mencarelli A, Distrutti E, Renga B, et al. Probiotics modulate intestinal expression of nuclear receptor and provide counter-regulatory signals to inflammation-driven adipose tissue activation. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e22978.

Article307. Miele E, Pascarella F, Giannetti E, Quaglietta L, Baldassano RN, Staiano A. Effect of a probiotic preparation (VSL#3) on induction and maintenance of remission in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:437–443.

Article308. Huynh HQ, deBruyn J, Guan L, et al. Probiotic preparation VSL#3 induces remission in children with mild to moderate acute ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009; 15:760–768.

Article309. Mardini HE, Grigorian AY. Probiotic mix VSL#3 is effective adjunctive therapy for mild to moderately active ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014; 20:1562–1567.

Article310. Toumi R, Abdelouhab K, Rafa H, et al. Beneficial role of the probiotic mixture Ultrabiotique on maintaining the integrity of intestinal mucosal barrier in DSS-induced experimental colitis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2013; 35:403–409.

Article311. Ghyselinck J, Verstrepen L, Moens F, et al. A 4-strain probiotic supplement influences gut microbiota composition and gut wall function in patients with ulcerative colitis. Int J Pharm. 2020; 587:119648.

Article312. Chen Y, Zhang L, Hong G, et al. Probiotic mixtures with aerobic constituent promoted the recovery of multi-barriers in DSS-induced chronic colitis. Life Sci. 2020; 240:117089.

Article313. Pilarczyk-Zurek M, Zwolinska-Wcislo M, Mach T, et al. Influence of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium combination on the gut microbiota, clinical course, and local gut inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis: a preliminary, single-center, open-label study. J Prob Health. 2017; 5:163.

Article314. Guslandi M, Mezzi G, Sorghi M, Testoni PA. Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000; 45:1462–1464.315. Generoso SV, Viana ML, Santos RG, et al. Protection against increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation induced by intestinal obstruction in mice treated with viable and heat-killed Saccharomyces boulardii. Eur J Nutr. 2011; 50:261–269.

Article316. Kelesidis T, Pothoulakis C. Efficacy and safety of the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii for the prevention and therapy of gastrointestinal disorders. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012; 5:111–125.

Article317. Bourreille A, Cadiot G, Le Dreau G, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii does not prevent relapse of Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 11:982–987.

Article318. Martín R, Chain F, Miquel S, et al. The commensal bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is protective in DNBS-induced chronic moderate and severe colitis models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014; 20:417–430.

Article319. Martín R, Miquel S, Benevides L, et al. Functional characterization of novel Faecalibacterium prausnitzii strains isolated from healthy volunteers: a step forward in the use of f. prausnitzii as a next-generation probiotic. Front Microbiol. 2017; 8:1226.

Article320. Carlsson AH, Yakymenko O, Olivier I, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii supernatant improves intestinal barrier function in mice DSS colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013; 48:1136–1144.

Article321. Martín R, Miquel S, Chain F, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii prevents physiological damages in a chronic low-grade inflammation murine model. BMC Microbiol. 2015; 15:67.

Article322. Zhou Y, Xu H, Xu J, et al. F. prausnitzii and its supernatant increase SCFAs-producing bacteria to restore gut dysbiosis in TNBS-induced colitis. AMB Express. 2021; 11:33.

Article323. Ma L, Shen Q, Lyu W, et al. Clostridium butyricum and its derived extracellular vesicles modulate gut homeostasis and ameliorate acute experimental colitis. Microbiol Spectr. 2022; 10:e0136822.

Article324. Zhou J, Li M, Chen Q, et al. Programmable probiotics modulate inflammation and gut microbiota for inflammatory bowel disease treatment after effective oral delivery. Nat Commun. 2022; 13:3432.

Article325. Bian X, Wu W, Yang L, et al. Administration of Akkermansia muciniphila ameliorates dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Front Microbiol. 2019; 10:2259.

Article326. Liu Q, Lu W, Tian F, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila exerts strain-specific effects on DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021; 11:698914.

Article327. Wang T, Shi C, Wang S, et al. Protective effects of Companilactobacillus crustorum MN047 against dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis: a fecal microbiota transplantation study. J Agric Food Chem. 2022; 70:1547–1561.

Article328. Bian X, Yang L, Wu W, et al. Pediococcus pentosaceus LI05 alleviates DSS-induced colitis by modulating immunological profiles, the gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid levels in a mouse model. Microb Biotechnol. 2020; 13:1228–1244.

Article329. Dong F, Xiao F, Li X, et al. Pediococcus pentosaceus CECT 8330 protects DSS-induced colitis and regulates the intestinal microbiota and immune responses in mice. J Transl Med. 2022; 20:33.

Article330. Huang YY, Wu YP, Jia XZ, et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum DMDL 9010 alleviates dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis and behavioral disorders by facilitating microbiotagut-brain axis balance. Food Funct. 2022; 13:411–424.

Article331. Delday M, Mulder I, Logan ET, Grant G. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ameliorates colon inflammation in preclinical models of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019; 25:85–96.

Article332. Kropp C, Le Corf K, Relizani K, et al. The Keystone commensal bacterium Christensenella minuta DSM 22607 displays anti-inflammatory properties both in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2021; 11:11494.

Article333. Rolfe VE, Fortun PJ, Hawkey CJ, Bath-Hextall F. Probiotics for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (4):CD004826.

Article334. Limketkai BN, Akobeng AK, Gordon M, Adepoju AA. Probiotics for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020; (7):CD006634.

Article335. Zhang XF, Guan XX, Tang YJ, et al. Clinical effects and gut microbiota changes of using probiotics, prebiotics or synbiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2021; 60:2855–2875.

Article336. Schultz M, Timmer A, Herfarth HH, Sartor RB, Vanderhoof JA, Rath HC. Lactobacillus GG in inducing and maintaining remission of Crohn’s disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2004; 4:5.

Article337. Bousvaros A, Guandalini S, Baldassano RN, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of Lactobacillus GG versus placebo in addition to standard maintenance therapy for children with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005; 11:833–839.

Article338. Fujimori S, Tatsuguchi A, Gudis K, et al. High dose probiotic and prebiotic cotherapy for remission induction of active Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 22:1199–1204.

Article339. Marteau P, Lémann M, Seksik P, et al. Ineffectiveness of Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 for prophylaxis of postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled GETAID trial. Gut. 2006; 55:842–847.

Article340. Mallon P, McKay D, Kirk S, Gardiner K. Probiotics for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; (4):CD005573.

Article341. Matthes H, Krummenerl T, Giensch M, Wolff C, Schulze J. Clinical trial: probiotic treatment of acute distal ulcerative colitis with rectally administered Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN). BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010; 10:13.

Article342. Petersen AM, Mirsepasi H, Halkjær SI, Mortensen EM, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Krogfelt KA. Ciprofloxacin and probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle add-on treatment in active ulcerative colitis: a double-blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:1498–1505.

Article343. Matsuoka K, Uemura Y, Kanai T, et al. Efficacy of Bifidobacterium breve fermented milk in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018; 63:1910–1919.

Article344. Pandey KR, Naik SR, Vakil BV. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2015; 52:7577–7587.

Article345. Ramirez-Farias C, Slezak K, Fuller Z, Duncan A, Holtrop G, Louis P. Effect of inulin on the human gut microbiota: stimulation of Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Br J Nutr. 2009; 101:541–550.

Article346. Vandeputte D, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, et al. Prebiotic inulintype fructans induce specific changes in the human gut microbiota. Gut. 2017; 66:1968–1974.

Article347. Akram W, Garud N, Joshi R. Role of inulin as prebiotics on inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Discov Ther. 2019; 13:1–8.

Article348. Hiel S, Bindels LB, Pachikian BD, et al. Effects of a diet based on inulin-rich vegetables on gut health and nutritional behavior in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019; 109:1683–1695.

Article349. Welters CF, Heineman E, Thunnissen FB, van den Bogaard AE, Soeters PB, Baeten CG. Effect of dietary inulin supplementation on inflammation of pouch mucosa in patients with an ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002; 45:621–627.

Article350. Rivière A, Selak M, Lantin D, Leroy F, De Vuyst L. Bifidobacteria and butyrate-producing colon bacteria: importance and strategies for their stimulation in the human gut. Front Microbiol. 2016; 7:979.

Article351. De Preter V, Vanhoutte T, Huys G, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus casei Shirota, Bifidobacterium breve, and oligofructoseenriched inulin on colonic nitrogen-protein metabolism in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007; 292:G358–G368.352. Morse AL, Dlusskaya EA, Valcheva R, Haynes KM, Gänzle MG, Dieleman LA. T2041 Prebiotic mixture of inulin plus oligofructose is effective adjunct therapy for treatment of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138(5 Suppl 1):S–619.

Article353. Azpiroz F, Dubray C, Bernalier-Donadille A, et al. Effects of scFOS on the composition of fecal microbiota and anxiety in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017; 29:e12911.

Article354. Zha Z, Lv Y, Tang H, et al. An orally administered butyratereleasing xylan derivative reduces inflammation in dextran sulphate sodium-induced murine colitis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020; 156:1217–1233.

Article355. Benjamin JL, Hedin CR, Koutsoumpas A, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fructo-oligosaccharides in active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2011; 60:923–929.

Article356. Casellas F, Borruel N, Torrejón A, et al. Oral oligofructose-enriched inulin supplementation in acute ulcerative colitis is well tolerated and associated with lowered faecal calprotectin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007; 25:1061–1067.

Article357. Rogha M, Esfahani MZ, Zargarzadeh AH. The efficacy of a synbiotic containing Bacillus coagulans in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014; 7:156–163.358. Darb Emamie A, Rajabpour M, Ghanavati R, et al. The effects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics on the reduction of IBD complications, a periodic review during 2009-2020. J Appl Microbiol. 2021; 130:1823–1838.

Article359. Steed H, Macfarlane GT, Blackett KL, et al. Clinical trial: the microbiological and immunological effects of synbiotic consumption: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in active Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 32:872–883.

Article360. Ishikawa H, Matsumoto S, Ohashi Y, et al. Beneficial effects of probiotic bifidobacterium and galacto-oligosaccharide in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled study. Digestion. 2011; 84:128–133.

Article361. Ivanovska TP, Mladenovska K, Zhivikj Z, et al. Synbiotic loaded chitosan-Ca-alginate microparticles reduces inflammation in the TNBS model of rat colitis. Int J Pharm. 2017; 527:126–134.

Article362. Kaur R, Gulati M, Singh SK. Role of synbiotics in polysaccharide assisted colon targeted microspheres of mesalamine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017; 95:438–450.

Article363. Son SJ, Koh JH, Park MR, et al. Effect of the Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG and tagatose as a synbiotic combination in a dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis murine model. J Dairy Sci. 2019; 102:2844–2853.

Article364. Seong G, Lee S, Min YW, et al. Effect of a synbiotic containing Lactobacillus paracasei and Opuntia humifusa on a murine model of irritable bowel syndrome. Nutrients. 2020; 12:3205.

Article365. Dos Santos Cruz BC, da Silva Duarte V, Giacomini A, et al. Synbiotic VSL#3 and yacon-based product modulate the intestinal microbiota and prevent the development of pre-neoplastic lesions in a colorectal carcinogenesis model. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020; 104:8837–8857.

Article366. Cappello C, Tremolaterra F, Pascariello A, Ciacci C, Iovino P. A randomised clinical trial (RCT) of a symbiotic mixture in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): effects on symptoms, colonic transit and quality of life. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013; 28:349–358.

Article367. Shavakhi A, Minakari M, Farzamnia S, et al. The effects of multi-strain probiotic compound on symptoms and qualityof-life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Adv Biomed Res. 2014; 3:140.368. Bogovič Matijašić B, Obermajer T, Lipoglavšek L, et al. Effects of synbiotic fermented milk containing Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5 and Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12 on the fecal microbiota of adults with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Dairy Sci. 2016; 99:5008–5021.

Article369. Brandt LJ, Borody TJ, Campbell J. Endoscopic fecal microbiota transplantation: “first-line” treatment for severe Clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011; 45:655–657.370. Smits LP, Bouter KE, de Vos WM, Borody TJ, Nieuwdorp M. Therapeutic potential of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2013; 145:946–953.

Article371. Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, et al. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015; 8:80–93.

Article372. Paramsothy S, Paramsothy R, Rubin DT, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2017; 11:1180–1199.

Article373. Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019; 321:156–164.

Article374. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:407–415.

Article375. Austin M, Mellow M, Tierney WM. Fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Med. 2014; 127:479–483.

Article376. Kelly CR, Ihunnah C, Fischer M, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in immunocompromised patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014; 109:1065–1071.

Article377. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 41:835–843.

Article378. Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015; 149:102–109.

Article379. Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017; 389:1218–1228.

Article380. Nusbaum DJ, Sun F, Ren J, et al. Gut microbial and metabolomic profiles after fecal microbiota transplantation in pediatric ulcerative colitis patients. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2018; 94:fiy133.

Article381. Sood A, Mahajan R, Singh A, et al. Role of faecal microbiota transplantation for maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019; 13:1311–1317.

Article382. Tian Y, Zhou Y, Huang S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis: a prospective clinical study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019; 19:116.

Article383. Colman RJ, Rubin DT. Fecal microbiota transplantation as therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:1569–1581.

Article384. Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015; 149:110–118.

Article385. Sokol H, Landman C, Seksik P, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to maintain remission in Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled study. Microbiome. 2020; 8:12.

Article386. Kunde S, Pham A, Bonczyk S, et al. Safety, tolerability, and clinical response after fecal transplantation in children and young adults with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013; 56:597–601.

Article387. Cui B, Li P, Xu L, et al. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation strategy: a pilot study for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. J Transl Med. 2015; 13:298.

Article388. Caldeira LF, Borba HH, Tonin FS, Wiens A, Fernandez-Llimos F, Pontarolo R. Fecal microbiota transplantation in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020; 15:e0238910.

Article389. Borody TJ, Paramsothy S, Agrawal G. Fecal microbiota transplantation: indications, methods, evidence, and future directions. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013; 15:337.

Article390. Angelberger S, Reinisch W, Makristathis A, et al. Temporal bacterial community dynamics vary among ulcerative colitis patients after fecal microbiota transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013; 108:1620–1630.

Article391. Suskind DL, Singh N, Nielson H, Wahbeh G. Fecal microbial transplant via nasogastric tube for active pediatric ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015; 60:27–29.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

- Microbial Modulation in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

- The interplay between host immune cells and gut microbiota in chronic inflammatory diseases

- Current Status and Prospects of Intestinal Microbiome Studies

- Gut Microbiota as Potential Orchestrators of Irritable Bowel Syndrome