Anesth Pain Med.

2023 Oct;18(4):439-444. 10.17085/apm.23085.

Severe pulmonary edema occurred during endobronchial ultrasound under monitored anesthesia care - A case report -

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, Korea

- 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, Korea

- KMID: 2550925

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.23085

Abstract

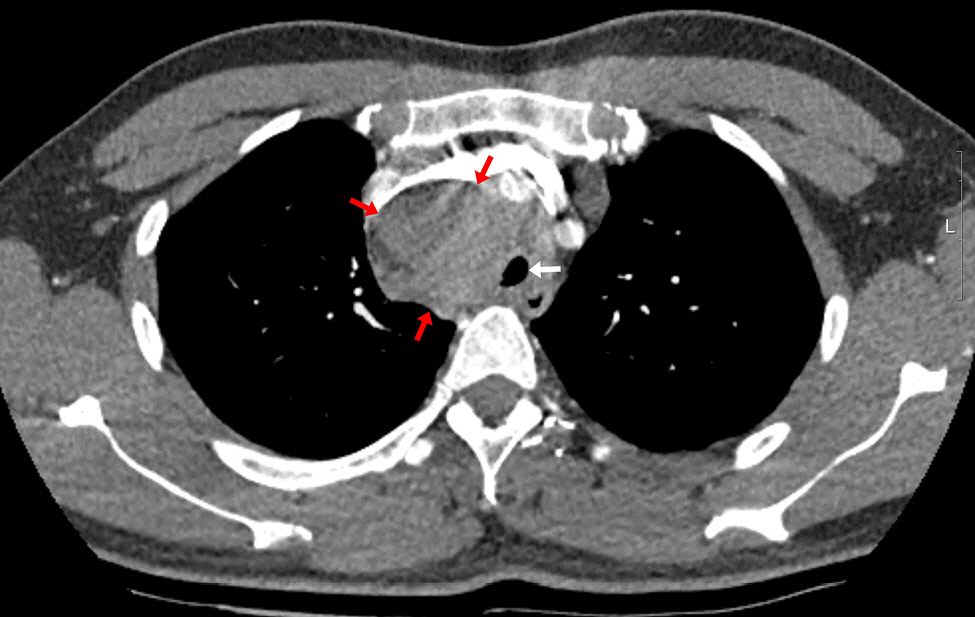

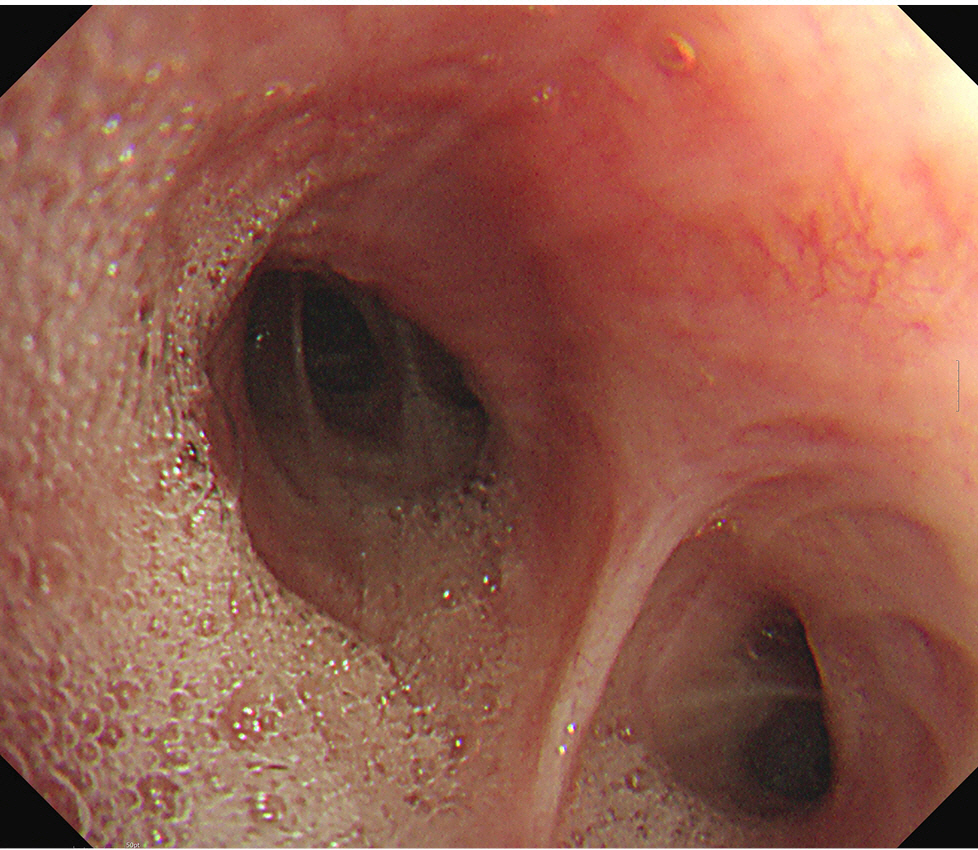

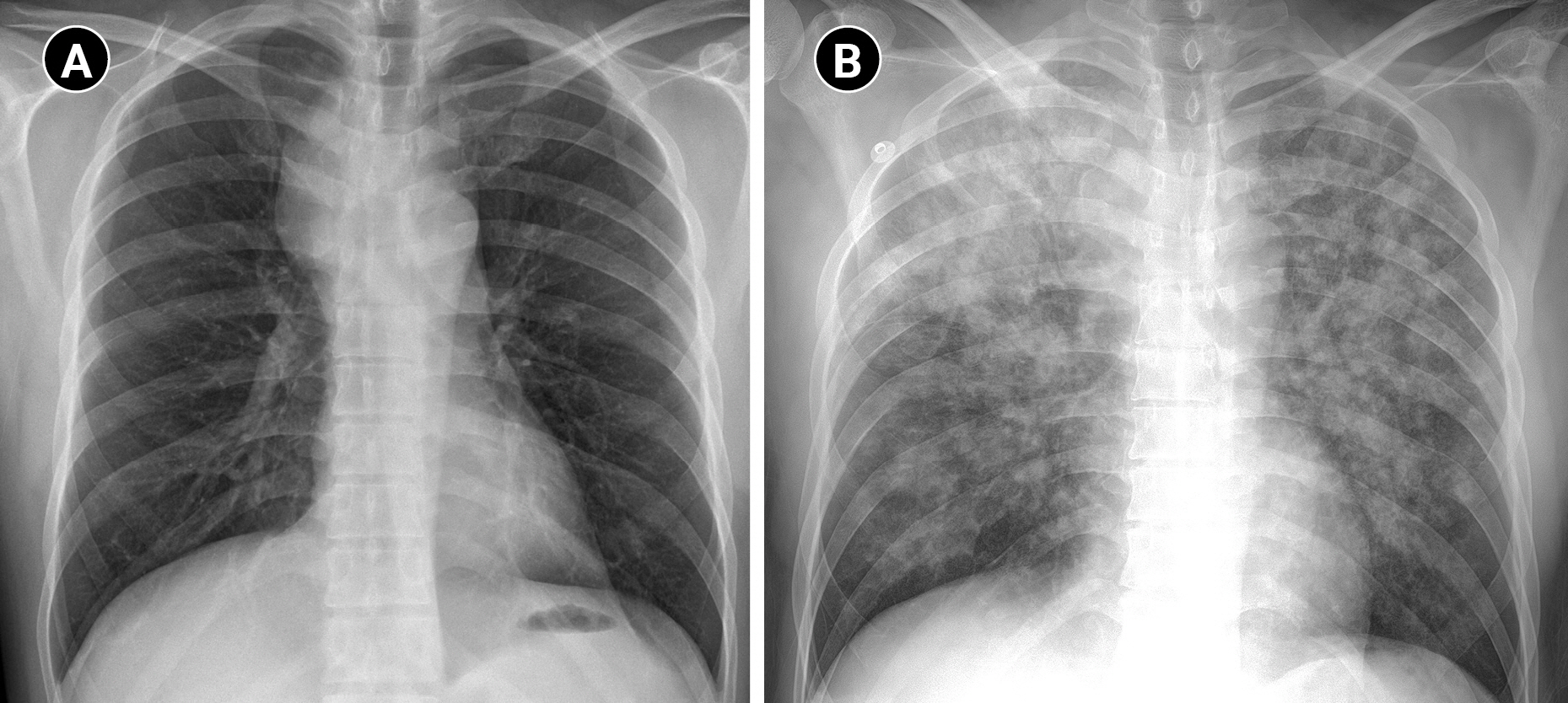

- Background

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) is widely used to diagnose lung cancer. Monitored anesthesia care (MAC) can enhance patient comfort and procedural conditions during EBUS. EBUS under MAC is usually safe but can lead to various complications. Case: A 34-year-old male who had increased sputum for two months showed an enlarged paratracheal lymph node and planned for lymph node biopsy by EBUS. During EBUS under MAC, an unexpected oxygen saturation decline required intervention. After intubation, copious frothy fluid was suctioned from the bronchi, and oxygenation was recovered. A narrowed trachea and the EBUS bronchoscope might have resulted in upper airway obstruction, and suction performed under these conditions might have caused pulmonary edema. The patient received non-invasive ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula and recovered without complications. Conclusions: When there is an expected risk of upper airway obstruction during EBUS, careful preoperative evaluation and preparation are essential to prevent negative pressure pulmonary edema.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Jiang J, Browning R, Lechtzin N, Huang J, Terry P, Wang KP. TBNA with and without EBUS: a comparative efficacy study for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2014; 6:416–20.2. Um SW, Kim HK, Jung SH, Han J, Lee KJ, Park HY, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound versus mediastinoscopy for mediastinal nodal staging of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015; 10:331–7.

Article3. Casal RF, Lazarus DR, Kuhl K, Nogueras-González G, Perusich S, Green LK, et al. Randomized trial of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration under general anesthesia versus moderate sedation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 191:796–803.

Article4. Douglas N, Ng I, Nazeem F, Lee K, Mezzavia P, Krieser R, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing high-flow nasal oxygen with standard management for conscious sedation during bronchoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2018; 73:169–76.

Article5. Hayama M, Izumo T, Matsumoto Y, Chavez C, Tsuchida T, Sasada S. Complications with endobronchial ultrasound with a guide sheath for the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions. Respiration. 2015; 90:129–35.

Article6. Miller MA, Levy P, Patel MM. Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department: what are the risks? Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005; 23:551–72.

Article7. Lee JH, Lee JH, Lee MH, Cho HO, Park SE. Postoperative negative pressure pulmonary edema following repetitive laryngospasm even after reversal of neuromuscular blockade by sugammadex: a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017; 70:95–9.

Article8. Tami TA, Chu F, Wildes TO, Kaplan M. Pulmonary edema and acute upper airway obstruction. Laryngoscope. 1986; 96:506–9.

Article9. Blakeman TC, Scott JB, Yoder MA, Capellari E, Strickland SL. AARC clinical practice guidelines: artificial airway suctioning. Respir Care. 2022; 67:258–71.

Article10. Hannania S, Barak M, Katz Y. Unilateral negative-pressure pulmonary edema in an infant during bronchoscopy. Pediatrics. 2004; 113:e501–3.

Article11. Bedolla-Pulido TR, Bedolla-Barajas M. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema associated with bronchospasm in a woman with no history of asthma]. Rev Alerg Mex. 2017; 64:386–9. Spanish.12. Practice Guidelines for Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia 2018: A Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia, the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Dental Association, American Society of Dentist Anesthesiologists, and Society of Interventional Radiology. Anesthesiology. 2018; 128:437–79.13. Lindholm CE, Ollman B, Snyder JV, Millen EG, Grenvik A. Cardiorespiratory effects of flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy in critically ill patients. Chest. 1978; 74:362–8.

Article14. Pue CA, Pacht ER. Complications of fiberoptic bronchoscopy at a university hospital. Chest. 1995; 107:430–2.

Article15. Huang CT, Ruan SY, Liao WY, Kuo YW, Lin CY, Tsai YJ, et al. Risk factors of pneumothorax after endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial biopsy for peripheral lung lesions. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e49125.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Unilateral pulmonary edema during an operation in patient with undiagnosed pheochromocytoma: A case report

- Unexpected Pulmonary Edema Associated with an Intranasal Spray of Phenylephrine during the Induction of General Anesthesia: A case report

- Acute Pulmonary Edema during Anesthesia and Operation - A case report

- Acute Postoperative Pulmonary Edema without Reasonable Causes: A Case Report

- Acute Pulmonary Edema in the Parturient Pretreated with Ritodrine during Cesarean Section under Epidural Anesthesia: A case report