J Korean Med Sci.

2024 Jan;39(2):e23. 10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e23.

Prognostic Factors for Predicting Post-COVID-19 Condition in Patients With COVID-19 in an Outpatient Setting

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 3Informatization Department, Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2550800

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e23

Abstract

- Background

Although data on post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) conditions are extensive, the prognostic factors affecting symptom duration in non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are currently not well known. We aimed to investigate the various prognostic factors affecting symptom duration among outpatients with COVID-19.

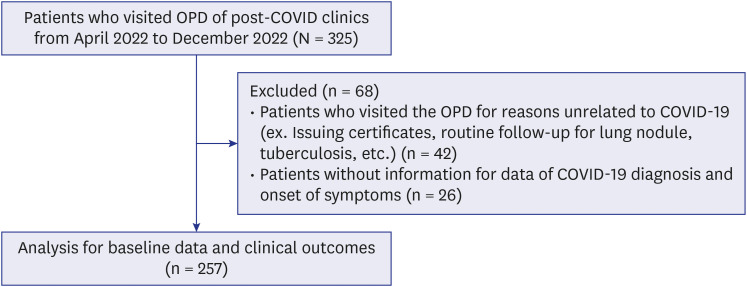

Methods

Data were analyzed from 257 patients who were diagnosed with mild COVID-19 and visited the ‘post-COVID-19 outpatient clinic’ between April and December 2022 after a mandatory isolation period. The symptom duration was measured from diagnosis to symptom resolution. Laboratory and pulmonary function test results from their first visit were collected.

Results

The mean age of patients was 55.7 years, and the median symptom duration was 57 days. The development of post-COVID-19 conditions (> 12 weeks) were significantly correlated with not using antiviral drugs, leukocytosis (white blood cell > 10,000/µL), lower 25(OH)D 3 levels, forced vital capacity (FVC) < 90% predicted, and presence of dyspnea and anxiety/depression. Additionally, in multivariable Cox regression analysis, not using antiviral drugs, lower 25(OH)D 3 levels, and having dyspnea were poor prognostic factors for longer symptom duration. Particularly, vitamin D deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) and not using antivirals during the acute phase were independent poor prognostic factors for both post-COVID-19 condition and longer symptom duration.

Conclusion

The non-use of antivirals, lower 25(OH)D 3 levels, leukocytosis, FVC < 90% predicted, and the presence of dyspnea and anxiety/depression symptoms could be useful prognostic factors for predicting post-COVID-19 condition in outpatients with COVID-19. We suggest that the use of antiviral agents during the acute phase and vitamin D supplements might help reduce COVID-19 symptom duration.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021; 27(4):601–615. PMID: 33753937.2. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021; 397(10270):220–232. PMID: 33428867.3. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020; 324(6):603–605. PMID: 32644129.4. Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):16144. PMID: 34373540.5. Michelen M, Manoharan L, Elkheir N, Cheng V, Dagens A, Hastie C, et al. Characterising long COVID: a living systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021; 6(9):e005427.6. Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Florencio LL, Cuadrado ML, Plaza-Manzano G, et al. Prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms in hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2021; 92:55–70. PMID: 34167876.7. World Health Organization. A Clinical Case Definition of Post COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus, 6 October 2021. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2021.8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Post-COVID conditions: information for healthcare providers. Updated 2023. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/post-covid-conditions.html .9. Butt AA, Dargham SR, Coyle P, Yassine HM, Al-Khal A, Abou-Samra AB, et al. COVID-19 disease severity in persons infected with Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 sublineages and association with vaccination status. JAMA Intern Med. 2022; 182(10):1097–1099. PMID: 35994264.10. Wolter N, Jassat W, Walaza S, Welch R, Moultrie H, Groome M, et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in South Africa: a data linkage study. Lancet. 2022; 399(10323):437–446. PMID: 35065011.11. Ulloa AC, Buchan SA, Daneman N, Brown KA. Estimates of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant severity in Ontario, Canada. JAMA. 2022; 327(13):1286–1288. PMID: 35175280.12. Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes S, Myles P, Williams T, Gokhale KM, et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med. 2022; 28(8):1706–1714. PMID: 35879616.13. Augustin M, Schommers P, Stecher M, Dewald F, Gieselmann L, Gruell H, et al. Post-COVID syndrome in non-hospitalised patients with COVID-19: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021; 6:100122. PMID: 34027514.14. Stavem K, Ghanima W, Olsen MK, Gilboe HM, Einvik G. Persistent symptoms 1.5–6 months after COVID-19 in non-hospitalised subjects: a population-based cohort study. Thorax. 2021; 76(4):405–407. PMID: 33273028.15. Tsampasian V, Elghazaly H, Chattopadhyay R, Debski M, Naing TKP, Garg P, et al. Risk factors associated with post-COVID-19 condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2023; 183(6):566–580. PMID: 36951832.16. Macintyre N, Crapo RO, Viegi G, Johnson DC, van der Grinten CP, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of the single-breath determination of carbon monoxide uptake in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2005; 26(4):720–735. PMID: 16204605.17. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005; 26(2):319–338. PMID: 16055882.18. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357(3):266–281. PMID: 17634462.19. Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, Billig Rose E, Shapiro NI, Files DC, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network - United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(30):993–998. PMID: 32730238.20. Oscanoa TJ, Amado J, Vidal X, Laird E, Ghashut RA, Romero-Ortuno R. The relationship between the severity and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infection and 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration - a metaanalysis. Adv Respir Med. 2021; 89(2):145–157. PMID: 33966262.21. Dror AA, Morozov N, Daoud A, Namir Y, Yakir O, Shachar Y, et al. Pre-infection 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels and association with severity of COVID-19 illness. PLoS One. 2022; 17(2):e0263069. PMID: 35113901.22. Nielsen NM, Junker TG, Boelt SG, Cohen AS, Munger KL, Stenager E, et al. Vitamin D status and severity of COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2022; 12(1):19823. PMID: 36396686.23. Dissanayake HA, de Silva NL, Sumanatilleke M, de Silva SD, Gamage KK, Dematapitiya C, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic role of vitamin D in COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022; 107(5):1484–1502. PMID: 34894254.24. Grant WB, Lahore H, McDonnell SL, Baggerly CA, French CB, Aliano JL, et al. Evidence that vitamin D supplementation could reduce risk of influenza and COVID-19 infections and deaths. Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):988. PMID: 32252338.25. Townsend L, Dyer AH, McCluskey P, O’Brien K, Dowds J, Laird E, et al. Investigating the relationship between vitamin D and persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2430. PMID: 34371940.26. Pizzini A, Aichner M, Sahanic S, Böhm A, Egger A, Hoermann G, et al. Impact of vitamin D deficiency on COVID-19-a prospective analysis from the CovILD registry. Nutrients. 2020; 12(9):2775. PMID: 32932831.27. Jung YH, Ha EH, Choe KW, Lee S, Jo DH, Lee WJ. Persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19 infection in Omicron era. J Korean Med Sci. 2022; 37(27):e213. PMID: 35818704.28. Song WJ, Hui CK, Hull JH, Birring SS, McGarvey L, Mazzone SB, et al. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir Med. 2021; 9(5):533–544. PMID: 33857435.29. Daneshkhah A, Agrawal V, Eshein A, Subramanian H, Roy HK, Backman V. Evidence for possible association of vitamin D status with cytokine storm and unregulated inflammation in COVID-19 patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020; 32(10):2141–2158. PMID: 32876941.30. Bilezikian JP, Bikle D, Hewison M, Lazaretti-Castro M, Formenti AM, Gupta A, et al. Mechanisms in endocrinology: vitamin D and COVID-19. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020; 183(5):R133–R147. PMID: 32755992.31. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19 - final report. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(19):1813–1826. PMID: 32445440.32. Grein J, Ohmagari N, Shin D, Diaz G, Asperges E, Castagna A, et al. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382(24):2327–2336. PMID: 32275812.33. Gottlieb RL, Vaca CE, Paredes R, Mera J, Webb BJ, Perez G, et al. Early remdesivir to prevent progression to severe COVID-19 in outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(4):305–315. PMID: 34937145.34. Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, Abreu P, Bao W, Wisemandle W, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2022; 386(15):1397–1408. PMID: 35172054.35. Kamal M, Abo Omirah M, Hussein A, Saeed H. Assessment and characterisation of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int J Clin Pract. 2021; 75(3):e13746. PMID: 32991035.36. Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B. Global prevalence of post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or long COVID: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022; 226(9):1593–1607. PMID: 35429399.37. Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021; 27(4):626–631. PMID: 33692530.38. Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Pellicer-Valero OJ, Navarro-Pardo E, Palacios-Ceña D, Florencio LL, Guijarro C, et al. Symptoms experienced at the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection as risk factor of long-term post-COVID symptoms: the LONG-COVID-EXP-CM multicenter study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022; 116:241–244. PMID: 35017102.39. Dhawan RT, Gopalan D, Howard L, Vicente A, Park M, Manalan K, et al. Beyond the clot: perfusion imaging of the pulmonary vasculature after COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2021; 9(1):107–116. PMID: 33217366.40. Hama Amin BJ, Kakamad FH, Ahmed GS, Ahmed SF, Abdulla BA, Mohammed SH, et al. Post COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis; a meta-analysis study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022; 77:103590. PMID: 35411216.41. Daines L, Zheng B, Elneima O, Harrison E, Lone NI, Hurst JR, et al. Characteristics and risk factors for post-COVID-19 breathlessness after hospitalisation for COVID-19. ERJ Open Res. 2023; 9(1):00274-2022. PMID: 36820079.42. Aminian A, Bena J, Pantalone KM, Burguera B. Association of obesity with postacute sequelae of COVID-19. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021; 23(9):2183–2188. PMID: 34060194.43. Gao M, Piernas C, Astbury NM, Hippisley-Cox J, O’Rahilly S, Aveyard P, et al. Associations between body-mass index and COVID-19 severity in 6·9 million people in England: a prospective, community-based, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021; 9(6):350–359. PMID: 33932335.44. Ye P, Pang R, Li L, Li HR, Liu SL, Zhao L. Both underweight and obesity are associated with an increased risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity. Front Nutr. 2021; 8:649422. PMID: 34692741.45. Zhu B, Feng X, Jiang C, Mi S, Yang L, Zhao Z, et al. Correlation between white blood cell count at admission and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021; 21(1):574. PMID: 34126954.46. Yang L, Jin J, Luo W, Gan Y, Chen B, Li W. Risk factors for predicting mortality of COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020; 15(11):e0243124. PMID: 33253244.47. Huang G, Kovalic AJ, Graber CJ. Prognostic value of leukocytosis and lymphopenia for coronavirus disease severity. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(8):1839–1841. PMID: 32384045.48. Zhang S, Bai W, Yue J, Qin L, Zhang C, Xu S, et al. Eight months follow-up study on pulmonary function, lung radiographic, and related physiological characteristics in COVID-19 survivors. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):13854. PMID: 34226597.49. Munker D, Veit T, Barton J, Mertsch P, Mümmler C, Osterman A, et al. Pulmonary function impairment of asymptomatic and persistently symptomatic patients 4 months after COVID-19 according to disease severity. Infection. 2022; 50(1):157–168. PMID: 34322859.50. Magnúsdóttir I, Lovik A, Unnarsdóttir AB, McCartney D, Ask H, Kõiv K, et al. Acute COVID-19 severity and mental health morbidity trajectories in patient populations of six nations: an observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2022; 7(5):e406–e416. PMID: 35298894.51. Renaud-Charest O, Lui LMW, Eskander S, Ceban F, Ho R, Di Vincenzo JD, et al. Onset and frequency of depression in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Res. 2021; 144:129–137. PMID: 34619491.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Post-COVID-19 Syndrome

- The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and chronic diseases

- Risk of COVID-19 Transmission from Infected Outpatients to Healthcare Workers in an Outpatient Clinic

- The Management of Thyroid Disease in COVID-19 Pandemic

- Post–Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pulmonary Fibrosis: Wait or Needs Intervention