Nutr Res Pract.

2023 Oct;17(5):855-869. 10.4162/nrp.2023.17.5.855.

Protective effect of Lycium barbarum leaf extracts on atopic dermatitis: in vitro and in vivo studies

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Food and Nutrition, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea

- KMID: 2546944

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4162/nrp.2023.17.5.855

Abstract

- BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic disease with an increasing incidence globally; therefore, there is a growing demand for natural compounds effective in treating dermatitis. In this study, the protective effects of Lycium barbarum leaves with and without chlorophyll (LLE and LLE[Ch-]) on AD were investigated in animal models of AD and HaCaT cells. Further, we investigated whether LLE and LLE(Ch-) show any differences in physiological activity.

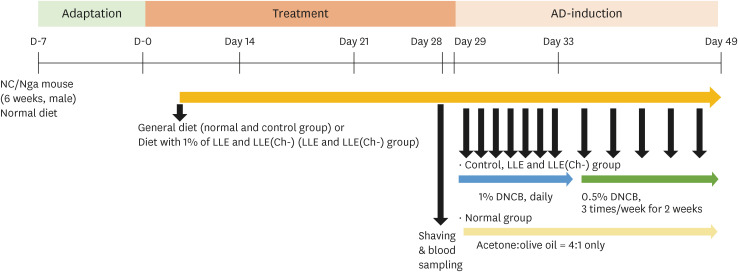

MATERIALS/METHODS

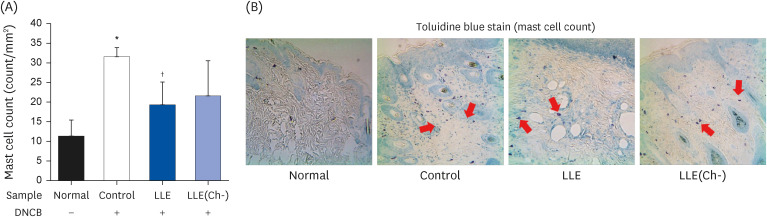

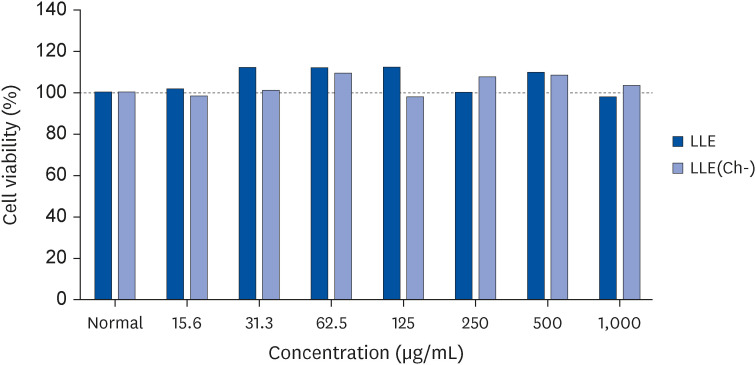

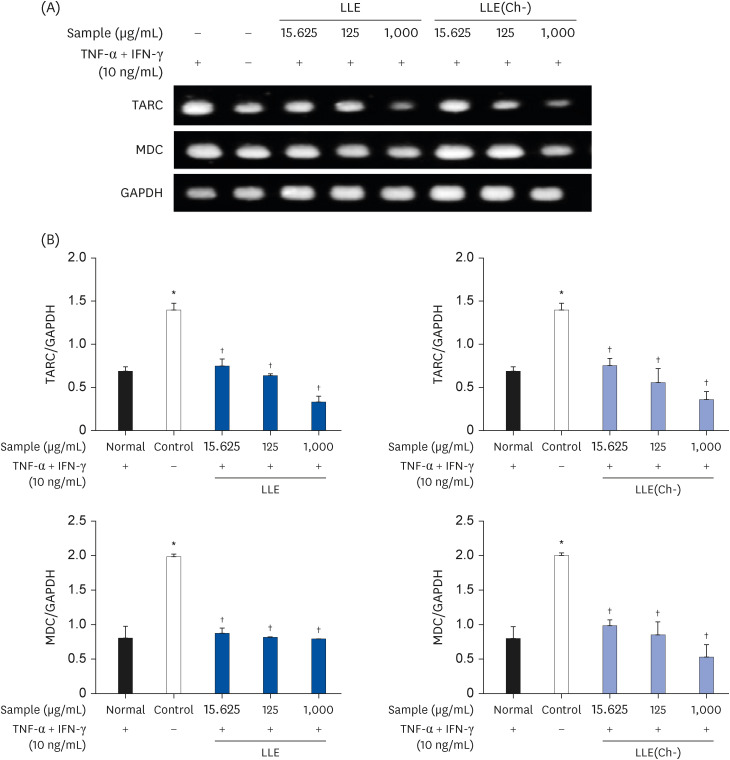

AD was induced by 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) for three weeks, while NC/Nga mice were fed LLE or LLE(Ch-) extracts for 7 weeks. Serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and cytokine (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, interleukin [IL]-6, and IL-4) concentrations and the degree of DNA fragmentation in lymphocytes were examined. A histopathological examination (haematoxylin & eosin staining and blue spots of toluidine) of the dorsal skin of mice was performed. To elucidate the mechanism of action, the expression of the thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) and macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC) were measured in HaCaT cells.

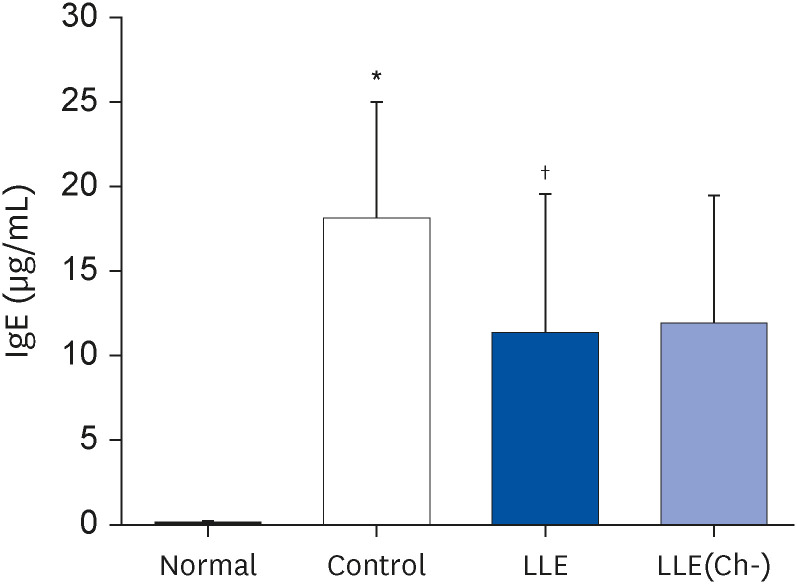

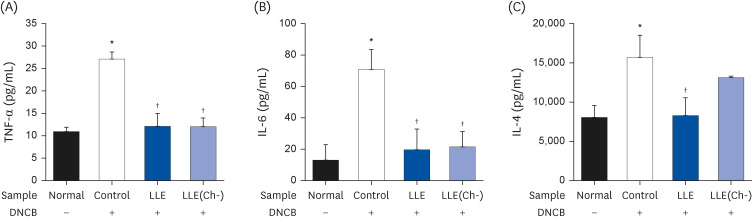

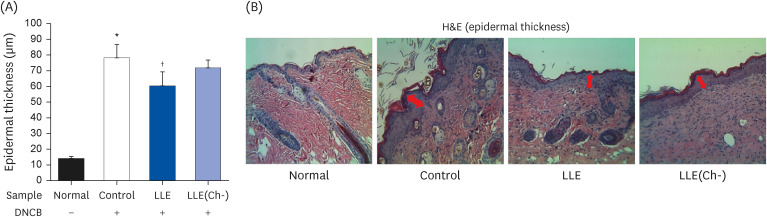

RESULTS

Serum IgE and cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) levels as well as DNA fragmentation of lymphocytes were significantly decreased in AD-induced mice treated with LLE or LLE(Ch-) compared to those of the control group. The epidermal thickness of the dorsal skin and mast cell infiltration in the LLE group significantly reduced compared to that in the control group. The LLE extracts showed no cytotoxicity up to 1,000 µg/mL in HaCaT cells. LLE or LLE(Ch-)-treated group showed a reduction of TARC and MDC in TNF-α-and IFN-γ-stimulated HaCaT cells.

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest that LLE potentially improves inflammation by reducing the expression of chemokines that inhibit T helper 2 cell migration. LLE(Ch-) showed similar effects to LLE on blood levels of IgE, TNF-α and IL-6 and protein expression in HaCat cells, but the ultimate effect of skin improvement was not statistically significant. Therefore, both LLE and LLE(Ch-) can be used as functional materials to alleviate AD, but LLE(Ch-) appears to require more research to improve inflammation.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Yang G, Seok JK, Kang HC, Cho YY, Lee HS, Lee JY. Skin barrier abnormalities and immune dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21:2867. PMID: 32326002.2. Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gulewicz KJ, Wang CQ, Mitsui H, Cardinale I, de Guzman Strong C, Krueger JG, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 130:1344–1354. PMID: 22951056.3. Leung DY, Guttman-Yassky E. Deciphering the complexities of atopic dermatitis: shifting paradigms in treatment approaches. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014; 134:769–779. PMID: 25282559.4. Renert-Yuval Y, Thyssen JP, Bissonnette R, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Hijnen D, Guttman-Yassky E. Biomarkers in atopic dermatitis-a review on behalf of the International Eczema Council. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021; 147:1174–1190.e1. PMID: 33516871.5. Luger T, Amagai M, Dreno B, Dagnelie MA, Liao W, Kabashima K, Schikowski T, Proksch E, Elias PM, Simon M, et al. Atopic dermatitis: role of the skin barrier, environment, microbiome, and therapeutic agents. J Dermatol Sci. 2021; 102:142–157. PMID: 34116898.6. Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gieler U, Girolomoni G, Lau S, Muraro A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018; 32:657–682. PMID: 29676534.7. Ye X, Jiang Y. Phytochemicals in Goji Berries. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press;2020.8. Yao R, Heinrich M, Zhao X, Wang Q, Wei J, Xiao P. What’s the choice for goji: Lycium barbarum L. or L. chinense Mill.? J Ethnopharmacol. 2021; 276:114185. PMID: 33964363.9. Zhao XQ, Guo S, Lu YY, Hua Y, Zhang F, Yan H, Shang EX, Wang HQ, Zhang WH, Duan JA. Lycium barbarum L. leaves ameliorate type 2 diabetes in rats by modulating metabolic profiles and gut microbiota composition. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020; 121:109559. PMID: 31734581.10. Mocan A, Zengin G, Simirgiotis M, Schafberg M, Mollica A, Vodnar DC, Crişan G, Rohn S. Functional constituents of wild and cultivated Goji (L. barbarum L.) leaves: phytochemical characterization, biological profile, and computational studies. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2017; 32:153–168. PMID: 28095717.11. Ma JF, Zhang H, Teh SS, Wang CW, Zhang Y, Hayford F, Wang L, Ma T, Dong Z, Zhang Y, et al. Goji berries as a potential natural antioxidant medicine: an insight into their molecular mechanisms of action. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019; 2019:2437397. PMID: 30728882.12. Paik S, Lee J, Yun TS, Park YC, Lee B, Son S, Ju J. Effects of planting density and cutting height on production of leaves for processing raw materials in goji berry. Korean J Med Crop Sci. 2020; 28:136–141.13. Nurhayati N, Suendo V. Isolation of chlorophyll a from spinach leaves and modification of center ion with Zn2+: study on its optical stability. J Matematika Sains. 2011; 16:65–70.14. Solymosi K, Mysliwa-Kurdziel B. Chlorophylls and their derivatives used in food industry and medicine. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2017; 17:1194–1222. PMID: 27719668.15. Porrarud S, Pranee A. Microencapsulation of Zn-chlorophyll pigment from Pandan leaf by spray drying and its characteristic. Int Food Res J. 2010; 17:1031–1042.16. Kim JE, Bae SM, Nam YR, Bae EY, Ly SY. Antioxidant activity of ethanol extract of Lycium barbarum’s leaf with removal of chlorophyll. J Nutr Health. 2019; 52:26–35.17. Bae SM, Kim JE, Bae EY, Kim KA, Ly SY. Anti-inflammatory effects of fruit and leaf extracts of Lycium barbarum in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264. 7 cells and animal model. J Nutr Health. 2019; 52:129–138.18. Nam KY, Go YE, Lee SY, Lee JS. A study on natural dye having the effects on the atopic dermatitis—Juniperus chinensis heartwood extract. Fibers Polym. 2013; 14:2045–2053.19. Cha KJ, Im MA, Gu A, Kim DH, Lee D, Lee JS, Lee JS, Kim IS. Inhibitory effect of Patrinia scabiosifolia Link on the development of atopic dermatitis-like lesions in human keratinocytes and NC/Nga mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017; 206:135–143. PMID: 28347830.20. Tice RR, Agurell E, Anderson D, Burlinson B, Hartmann A, Kobayashi H, Miyamae Y, Rojas E, Ryu JC, Sasaki YF. Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2000; 35:206–221. PMID: 10737956.21. Trautmann A, Akdis M, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Disch R, Bröcker EB, Blaser K, Akdis CA. Targeting keratinocyte apoptosis in the treatment of atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001; 108:839–846. PMID: 11692113.22. Baugh JA, Bucala R. Mechanisms for modulating TNF alpha in immune and inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2001; 4:635–650.23. Choi Y, Kim MS, Hwang JK. Inhibitory effects of panduratin A on allergy-related mediator production in rat basophilic leukemia mast cells. Inflammation. 2012; 35:1904–1915. PMID: 22864999.24. Peng W, Novak N. Pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015; 45:566–574. PMID: 25610977.25. Otsuka A, Nomura T, Rerknimitr P, Seidel JA, Honda T, Kabashima K. The interplay between genetic and environmental factors in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Immunol Rev. 2017; 278:246–262. PMID: 28658541.26. Danso MO, van Drongelen V, Mulder A, van Esch J, Scott H, van Smeden J, El Ghalbzouri A, Bouwstra JA. TNF-α and Th2 cytokines induce atopic dermatitis-like features on epidermal differentiation proteins and stratum corneum lipids in human skin equivalents. J Invest Dermatol. 2014; 134:1941–1950. PMID: 24518171.27. Diehl S, Rincón M. The two faces of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 differentiation. Mol Immunol. 2002; 39:531–536. PMID: 12431386.28. Nguyen SM, Rupprecht CP, Haque A, Pattanaik D, Yusin J, Krishnaswamy G. Mechanisms governing anaphylaxis: inflammatory cells, mediators, endothelial gap junctions and beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22:7785. PMID: 34360549.29. Ji H, Li XK. Oxidative stress in atopic dermatitis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016; 2016:2721469. PMID: 27006746.30. Tsukahara H, Shibata R, Ohshima Y, Todoroki Y, Sato S, Ohta N, Hiraoka M, Yoshida A, Nishima S, Mayumi M. Oxidative stress and altered antioxidant defenses in children with acute exacerbation of atopic dermatitis. Life Sci. 2003; 72:2509–2516. PMID: 12650859.31. Omata N, Tsukahara H, Ito S, Ohshima Y, Yasutomi M, Yamada A, Jiang M, Hiraoka M, Nambu M, Deguchi Y, et al. Increased oxidative stress in childhood atopic dermatitis. Life Sci. 2001; 69:223–228. PMID: 11441912.32. Werfel T, Allam JP, Biedermann T, Eyerich K, Gilles S, Guttman-Yassky E, Hoetzenecker W, Knol E, Simon HU, Wollenberg A, et al. Cellular and molecular immunologic mechanisms in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016; 138:336–349. PMID: 27497276.33. Proksch E, Fölster-Holst R, Jensen JM. Skin barrier function, epidermal proliferation and differentiation in eczema. J Dermatol Sci. 2006; 43:159–169. PMID: 16887338.34. Kawakami T, Ando T, Kimura M, Wilson BS, Kawakami Y. Mast cells in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009; 21:666–678. PMID: 19828304.35. Kritas SK, Saggini A, Varvara G, Murmura G, Caraffa A, Antinolfi P, Toniato E, Pantalone A, Neri G, Frydas S, et al. Impact of mast cells on the skin. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2013; 26:855–859. PMID: 24355220.36. Saeki H, Tamaki K. Thymus and activation regulated chemokine (TARC)/CCL17 and skin diseases. J Dermatol Sci. 2006; 43:75–84. PMID: 16859899.37. Nakazato J, Kishida M, Kuroiwa R, Fujiwara J, Shimoda M, Shinomiya N. Serum levels of Th2 chemokines, CCL17, CCL22, and CCL27, were the important markers of severity in infantile atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008; 19:605–613. PMID: 18266834.38. Masci A, Carradori S, Casadei MA, Paolicelli P, Petralito S, Ragno R, Cesa S. Lycium barbarum polysaccharides: extraction, purification, structural characterisation and evidence about hypoglycaemic and hypolipidaemic effects. A review. Food Chem. 2018; 254:377–389. PMID: 29548467.39. Zhou ZQ, Xiao J, Fan HX, Yu Y, He RR, Feng XL, Kurihara H, So KF, Yao XS, Gao H. Polyphenols from wolfberry and their bioactivities. Food Chem. 2017; 214:644–654. PMID: 27507521.40. Jin M, Huang Q, Zhao K, Shang P. Biological activities and potential health benefit effects of polysaccharides isolated from Lycium barbarum L. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013; 54:16–23. PMID: 23200976.41. Tian X, Liang T, Liu Y, Ding G, Zhang F, Ma Z. Extraction, structural characterization, and biological functions of Lycium Barbarum polysaccharides: a review. Biomolecules. 2019; 9:389. PMID: 31438522.42. Cheng J, Zhou ZW, Sheng HP, He LJ, Fan XW, He ZX, Sun T, Zhang X, Zhao RJ, Gu L, et al. An evidence-based update on the pharmacological activities and possible molecular targets of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014; 9:33–78.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Antioxidant activity of ethanol extract of Lycium barbarum's leaf with removal of chlorophyll

- Protective effect of chlorophyllremoved ethanol extract of Lycium barbarum leaves against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Anti-Inflammatory Herbal Extracts and Their Drug Discovery Perspective in Atopic Dermatitis

- Anti-inflammatory effects of fruit and leaf extracts of Lycium barbarum in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 cells and animal model

- Two Cases of Atopic Dermatitis Developing Ocular Complication and Immunological Disturbance