Obstet Gynecol Sci.

2023 Sep;66(5):449-454. 10.5468/ogs.23033.

Differential trend of mild and severe preeclampsia among nulliparous women: a population-based study of South Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Public Health Science, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University School of Medicine, Seongnam, Korea

- 3Department of Public Health, Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- 4Department of Preventive Medicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2545891

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.23033

Abstract

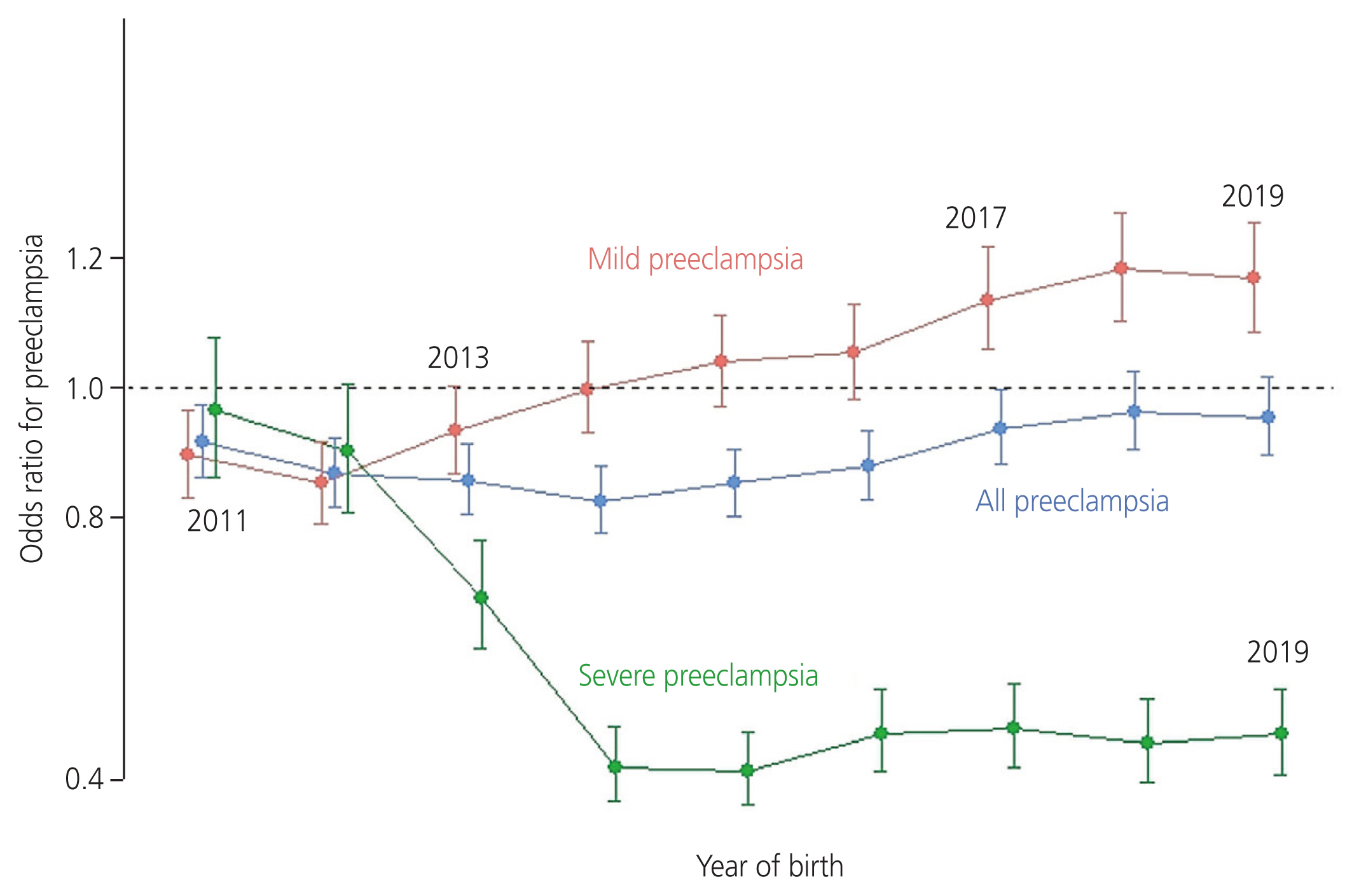

- We explored the annual risks of mild and severe preeclampsia (PE) among nulliparous women. Using the National Health Information Database of South Korea, 1,317,944 nulliparous women who gave live births were identified. Mild PE increased from 0.9% in 2010 to 1.4% in 2019 (P for trend=0.006), while severe PE decreased from 0.4% in 2010 to 0.3% in 2019 (P=0.049). The incidence of all types of PE (mild and severe) showed no linear change (P=0.514). Adjusted odds ratio (OR) of severe PE decreased in 2013 (0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.60, 0.77) and beyond compared to that in 2010, while the OR of mild PE increased in 2017 (1.14; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.22) and beyond. Mild PE was found to be less likely to progress to the severe form since 2010; however, the overall risk of PE among women did not change.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Atallah A, Lecarpentier E, Goffinet F, Doret-Dion M, Gaucherand P, Tsatsaris V. Aspirin for prevention of preeclampsia. Drugs. 2017; 77:1819–31.2. Ramos JGL, Sass N, Costa SHM. Preeclampsia. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017; 39:496–512.3. Freeman RK, Nageotte MP. Comments on American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists practice bulletin no. 106. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010; 202:411–2.4. Jung E, Romero R, Yeo L, Gomez-Lopez N, Chaemsaithong P, Jaovisidha A, et al. The etiology of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022; 226:S844–66.5. Sole KB, Staff AC, Laine K. Maternal diseases and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy across gestational age groups. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2021; 25:25–33.6. Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, Karumanchi SA, McCarthy FP, Saito S, et al. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis, and management recommendations for international practice. Hypertension. 2018; 72:24–43.7. Bartsch E, Medcalf KE, Park AL, Ray JG. Clinical risk factors for pre-eclampsia determined in early pregnancy: systematic review and meta-analysis of large cohort studies. BMJ. 2016; 353:i1753.8. Petersen SH, Bergh C, Gissler M, Åsvold BO, Romundstad LB, Tiitinen A, et al. Time trends in placenta-mediated pregnancy complications after assisted reproductive technology in the Nordic countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 223:226e1–226.e19.9. Wang W, Xie X, Yuan T, Wang Y, Zhao F, Zhou Z, et al. Epidemiological trends of maternal hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21:364.10. Roberts CL, Ford JB, Algert CS, Antonsen S, Chalmers J, Cnattingius S, et al. Population-based trends in pregnancy hypertension and pre-eclampsia: an international comparative study. BMJ Open. 2011; 1:e000101.11. Sole KB, Staff AC, Räisänen S, Laine K. Substantial decrease in preeclampsia prevalence and risk over two decades: a population-based study of 1,153,227 deliveries in Norway. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2022; 28:21–7.12. Noh Y, Choe SA, Kim WJ, Shin JY. Discontinuation and re-initiation of antidepressants during pregnancy: a nationwide cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2022; 298:500–7.13. Choe SA, Min HS, Cho SI. The income-based disparities in preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage: a study of the Korean National Health Insurance cohort data from 2002 to 2013. Springerplus. 2016; 5:895.14. Choe SA, Min HS, Cho SI. Decreased risk of preeclampsia after the introduction of universal voucher scheme for antenatal care and birth services in the Republic of Korea. Matern Child Health J. 2017; 21:222–7.15. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Healthcare service provision statistics (tests and surgeries) [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;c2023. [cited 2023 Mar 3]. Available from: https://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olapDiagBhvInfoTab1.do#none .16. Lee SY, Choi IS. Policy support for medical expenses on pregnancy and delivery: the kookmin haengbok card program [Internet]. Sejong: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;c2016. [cited 2023 Mar 3]. Available from: https://repository.kihasa.re.kr/handle/201002/20819 .17. National Legal Information Center. Mother and child health act [Internet]. Sejong: National Legal Information Center;c2021. [cited 2023 Mar 3]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menuId=2§ion=lawNm&query=MOTHER+AND+CHILD+HEALTH+ACT&x=0&y=0#liBgcolor1 .18. Xiao J, Shen F, Xue Q, Chen G, Zeng K, Stone P, et al. Is ethnicity a risk factor for developing preeclampsia? An analysis of the prevalence of preeclampsia in China. J Hum Hypertens. 2014; 28:694–8.19. Vata PK, Chauhan NM, Nallathambi A, Hussein F. Assessment of prevalence of preeclampsia from Dilla region of Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2015; 8:816.20. David M, Naicker T. The complement system in preeclampsia: a review of its activation and endothelial injury in the triad of COVID 19 infection and HIV-associated preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2023; 66:253–69.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Clinical Usefulness of Elevated Plasma Homocyst (e) ine Levels in Nulliparous Pregnant Women With Preeclampsia before Their Delivery as a Risk Factor

- Study on the Hematologic and Blood Chemical Tests in Preelcampsia

- Plasma Fibronectin Levels in Preeclampsia

- Angiotensinogen, Thermolabile Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase and Factor V Gene Variants among Korean Women with Preeclampsia, as Risk Factors

- Point Mutations in a Mitochondrial Transfer RiboNucleic Acid Gene in South Korean Women with Preeclampsia