J Korean Med Sci.

2023 Aug;38(31):e241. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e241.

Association Between Oral Health and Airflow Limitation: Analysis Using a Nationwide Survey in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea

- 2Department of Epidemiology and Health Informatics, Korea University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Conservative Dentistry, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea

- 4Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea

- 5Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Konkuk University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Biochemistry, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea

- 7Division of Pulmonary Medicine and Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2544960

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e241

Abstract

- Background

Although poor oral health is a common comorbidity in individuals with airflow limitation (AFL), few studies have comprehensively evaluated this association. Furthermore, the association between oral health and the severity of AFL has not been well elucidated.

Methods

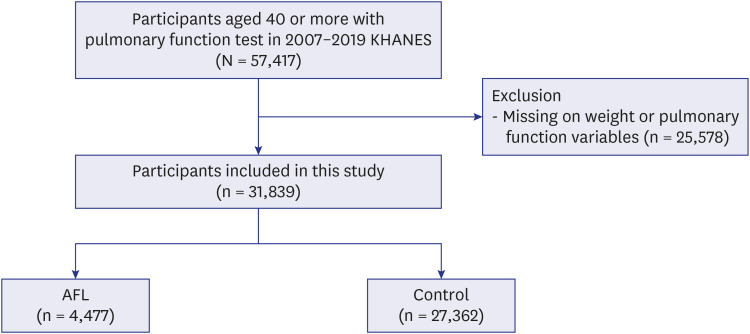

Using a population-based nationwide survey, we classified individuals according to the presence or absence of AFL defined as pre-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity < 0.7. Using multivariable logistic regression analyses, we evaluated the association between AFL severity and the number of remaining teeth; the presence of periodontitis; the Decayed, Missing, and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index; and denture wearing.

Results

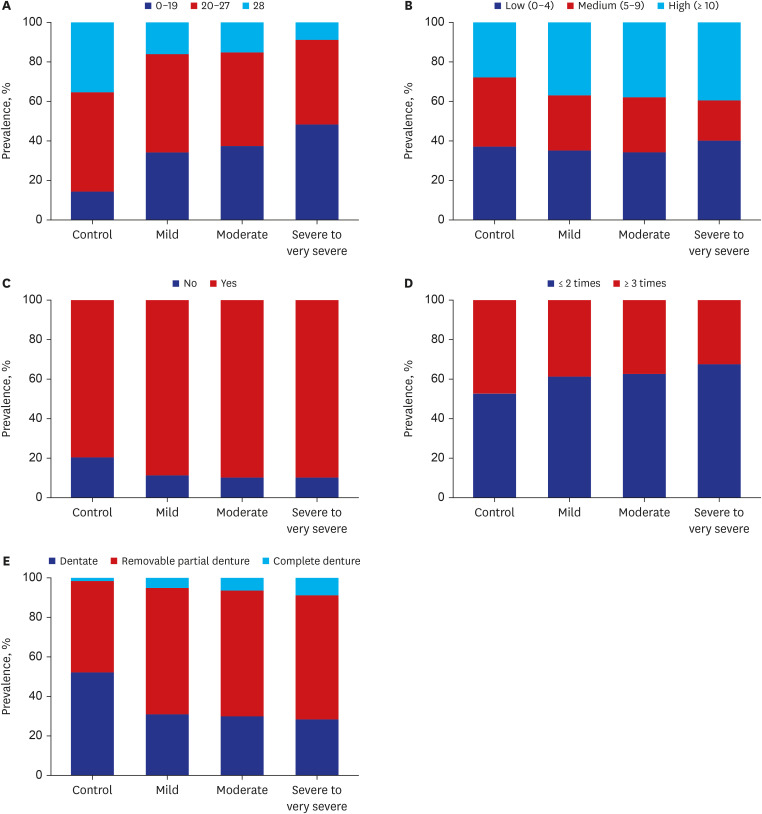

Among the 31,839 participants, 14% had AFL. Compared with the control group, the AFL group had a higher proportion of periodontitis (88.8% vs. 79.4%), complete denture (6.2% vs. 1.6%), and high DMFT index (37.3% vs. 27.8%) (P < 0.001 for all). In multivariable analyses, denture status: removable partial denture (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.12; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.04–1.20) and complete denture (aOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.01– 2.05), high DMFT index (aOR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02–1.24), and fewer permanent teeth (0–19; aOR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.12–1.52) were significantly associated with AFL. Furthermore, those with severe to very severe AFL had a significantly higher proportion of complete denture (aOR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.11–3.71) and fewer remaining teeth (0–19; aOR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.57–3.01).

Conclusion

Denture wearing, high DMFT index, and fewer permanent teeth are significantly associated with AFL. Furthermore, a reduced number of permanent teeth (0–19) was significantly related to the severity of AFL. Therefore, physicians should pay attention to oral health in managing patients with AFL, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Yang B, Choi H, Lim JH, Park HY, Kang D, Cho J, et al. The disease burden of bronchiectasis in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a national database study in Korea. Ann Transl Med. 2019; 7(23):770. PMID: 32042786.2. Sullivan SD, Ramsey SD, Lee TA. The economic burden of COPD. Chest. 2000; 117(2):Suppl. 5S–9S. PMID: 10673466.3. Chapman KR, Mannino DM, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, Buist AS, Thun MJ, et al. Epidemiology and costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2006; 27(1):188–207. PMID: 16387952.4. Lee H, Shin SH, Gu S, Zhao D, Kang D, Joi YR, et al. Racial differences in comorbidity profile among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Med. 2018; 16(1):178. PMID: 30285854.5. Negewo NA, Gibson PG, McDonald VM. COPD and its comorbidities: impact, measurement and mechanisms. Respirology. 2015; 20(8):1160–1171. PMID: 26374280.6. Chen W, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, FitzGerald JM. Risk of cardiovascular comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015; 3(8):631–639. PMID: 26208998.7. Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghé B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31(1):204–212. PMID: 18166598.8. Sapey E, Yonel Z, Edgar R, Parmar S, Hobbins S, Newby P, et al. The clinical and inflammatory relationships between periodontitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2020; 47(9):1040–1052. PMID: 32567697.9. Kim SW, Han K, Kim SY, Park CK, Rhee CK, Yoon HK. The relationship between the number of natural teeth and airflow obstruction: a cross-sectional study using data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015; 11:13–21. PMID: 26730184.10. Hayes C, Sparrow D, Cohen M, Vokonas PS, Garcia RI. The association between alveolar bone loss and pulmonary function: the VA Dental Longitudinal Study. Ann Periodontol. 1998; 3(1):257–261. PMID: 9722709.11. Scannapieco FA, Ho AW. Potential associations between chronic respiratory disease and periodontal disease: analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Periodontol. 2001; 72(1):50–56. PMID: 11210073.12. Barros SP, Suruki R, Loewy ZG, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. A cohort study of the impact of tooth loss and periodontal disease on respiratory events among COPD subjects: modulatory role of systemic biomarkers of inflammation. PLoS One. 2013; 8(8):e68592. PMID: 23950871.13. Wang Z, Zhou X, Zhang J, Zhang L, Song Y, Hu FB, et al. Periodontal health, oral health behaviours, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2009; 36(9):750–755. PMID: 19614723.14. Azarpazhooh A, Leake JL. Systematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral health. J Periodontol. 2006; 77(9):1465–1482. PMID: 16945022.15. Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, Boje Jensen G, Divo M, Faner R, et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373(2):111–122. PMID: 26154786.16. Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2005; 58(3):230–242.17. Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, Barjaktarevic IZ, Cooper BG, Hall GL, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society technical statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200(8):e70–e88. PMID: 31613151.18. Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects beyond the lungs. PLoS Med. 2010; 7(3):e1000220. PMID: 20305715.19. A guide to the UK Adult Dental Health Survey 1998. Br Dent J. 2001; Spec No:1–56.20. Sheiham A, Steele JG, Marcenes W, Finch S, Walls AW. The impact of oral health on stated ability to eat certain foods; findings from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of Older People in Great Britain. Gerodontology. 1999; 16(1):11–20. PMID: 10687504.21. Shin HS, Ahn YS, Lim DS. Association between the number of existing permanent teeth and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dent Hyg Sci. 2016; 16(3):217–224.22. World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2013.23. Hancocks S. The FDI’s first ten years, 1900-1910. Fédération Dentaire Internationale. Int Dent J. 2000; 50(4):175–183. PMID: 11042817.24. Cappelli DP, Mobley CC. Prevention in Clinical Oral Health Care. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences;2007.25. Klein H, Palmer C, Knutson J. Dental status and dental needs of elementary school children. Public Health Rep. 1938; 53:751–765.26. Kim MK, Lee WY, Kang JH, Kang JH, Kim BT, Kim SM, et al. 2014 clinical practice guidelines for overweight and obesity in Korea. Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 29(4):405–409.27. Shin SH, Park J, Cho J, Sin DD, Lee H, Park HY. Severity of airflow obstruction and work loss in a nationwide population of working age. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1):9674. PMID: 29946117.28. Lee H, Rhee CK, Lee BJ, Choi DC, Kim JA, Kim SH, et al. Impacts of coexisting bronchial asthma on severe exacerbations in mild-to-moderate COPD: results from a national database. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016; 11:775–783. PMID: 27143869.29. Yang B, Jang HJ, Chung SJ, Yoo SJ, Kim T, Kim SH, et al. Factors associated with bronchiectasis in Korea: a national database study. Ann Transl Med. 2020; 8(21):1350. PMID: 33313095.30. Sacks DB, Bruns DE, Goldstein DE, Maclaren NK, McDonald JM, Parrott M. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem. 2002; 48(3):436–472. PMID: 11861436.31. Carey RM, Whelton PK. 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 168(5):351–358. PMID: 29357392.32. Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Endocr Pract. 2017; 23(Suppl 2):1–87.33. Chung JH, Hwang HJ, Kim SH, Kim TH. Associations between periodontitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the 2010 to 2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2016; 87(8):864–871. PMID: 26912338.34. Khijmatgar S, Belur G, Venkataram R, Karobari MI, Marya A, Shetty V, et al. Oral candidal load and oral health status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients: a case-cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2021; 2021:5548746. PMID: 34545329.35. Gaeckle NT, Heyman B, Criner AJ, Criner GJ. Markers of dental health correlate with daily respiratory symptoms in COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018; 5(2):97–105. PMID: 30374447.36. Glass RT, Conrad RS, Bullard JW, Goodson LB, Mehta N, Lech SJ, et al. Evaluation of microbial flora found in previously worn prostheses from the Northeast and Southwest regions of the United States. J Prosthet Dent. 2010; 103(6):384–389. PMID: 20493328.37. Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW, Casaburi R, Emery CF, Mahler DA, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2007; 131(5):Suppl. 4S–42S. PMID: 17494825.38. Rahman N, Walls A. Chapter 12: nutrient deficiencies and oral health. Monogr Oral Sci. 2020; 28:114–124. PMID: 31940618.39. Yoo KH, Kim YS, Sheen SS, Park JH, Hwang YI, Kim SH, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008. Respirology. 2011; 16(4):659–665. PMID: 21342331.40. Kim DS, Kim YS, Jung KS, Chang JH, Lim CM, Lee JH, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: a population-based spirometry survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005; 172(7):842–847. PMID: 15976382.41. Kim Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiol Health. 2014; 36:e2014002. PMID: 24839580.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Association between Albuminuria and Severity of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The 8th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2019)

- Risk Factors for Unawareness of Obstructive Airflow Limitation among Adults with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Pathophysiology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Symptom Questionnaire and Laboratory Findings in Subjects with Airflow Limitation: a Nation-wide Survey

- Effect of Airflow Limitation on Acute Exacerbations in Patients with Destroyed Lungs by Tuberculosis