Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg.

2023 May;27(2):201-210. 10.14701/ahbps.22-064.

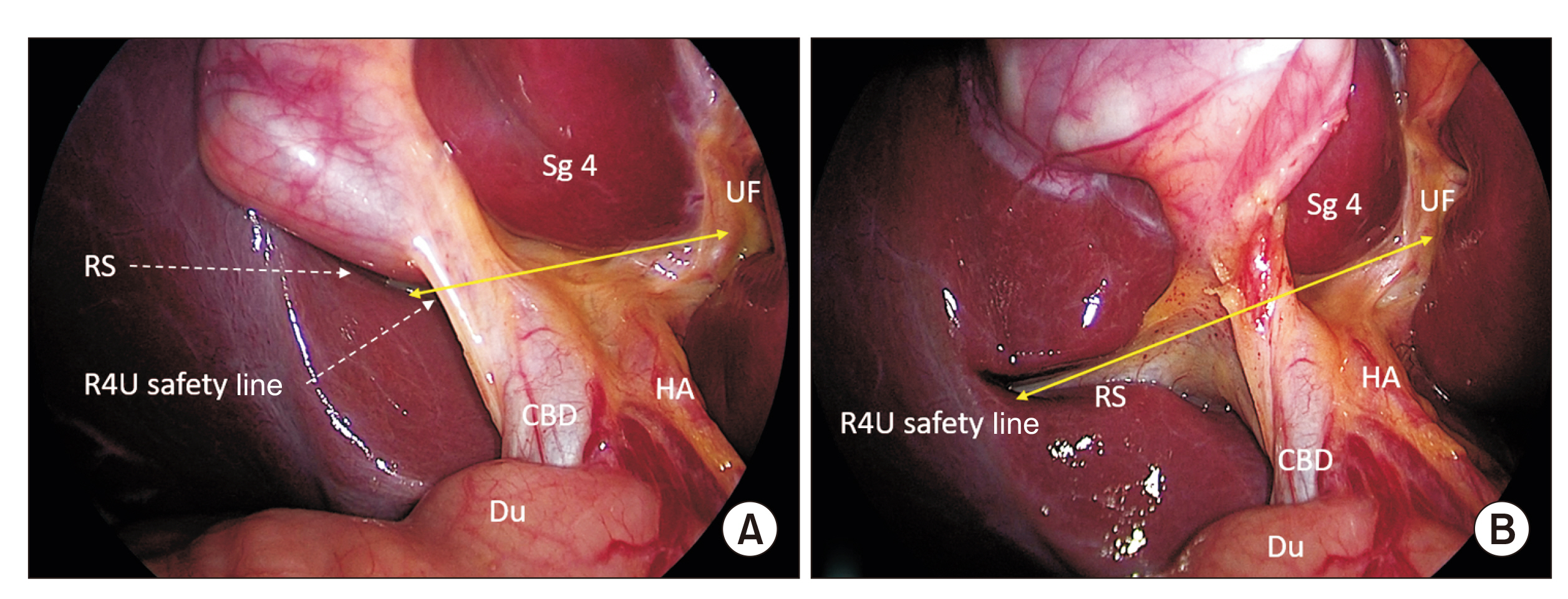

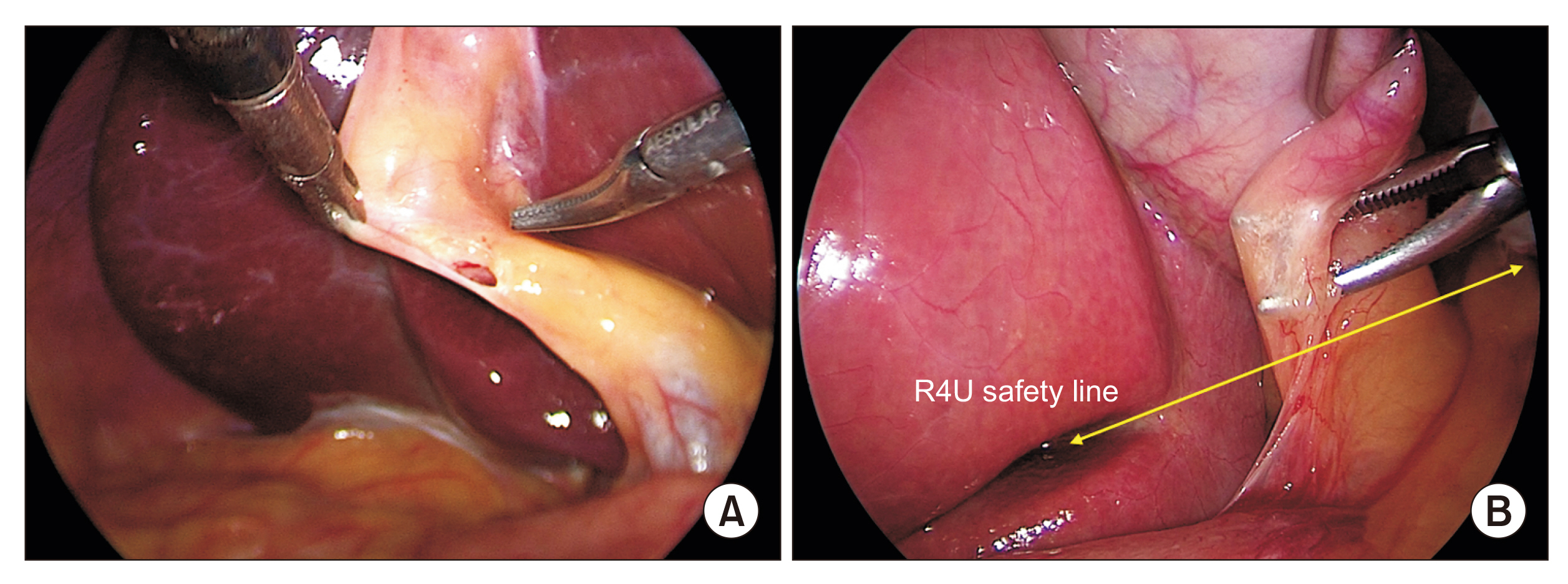

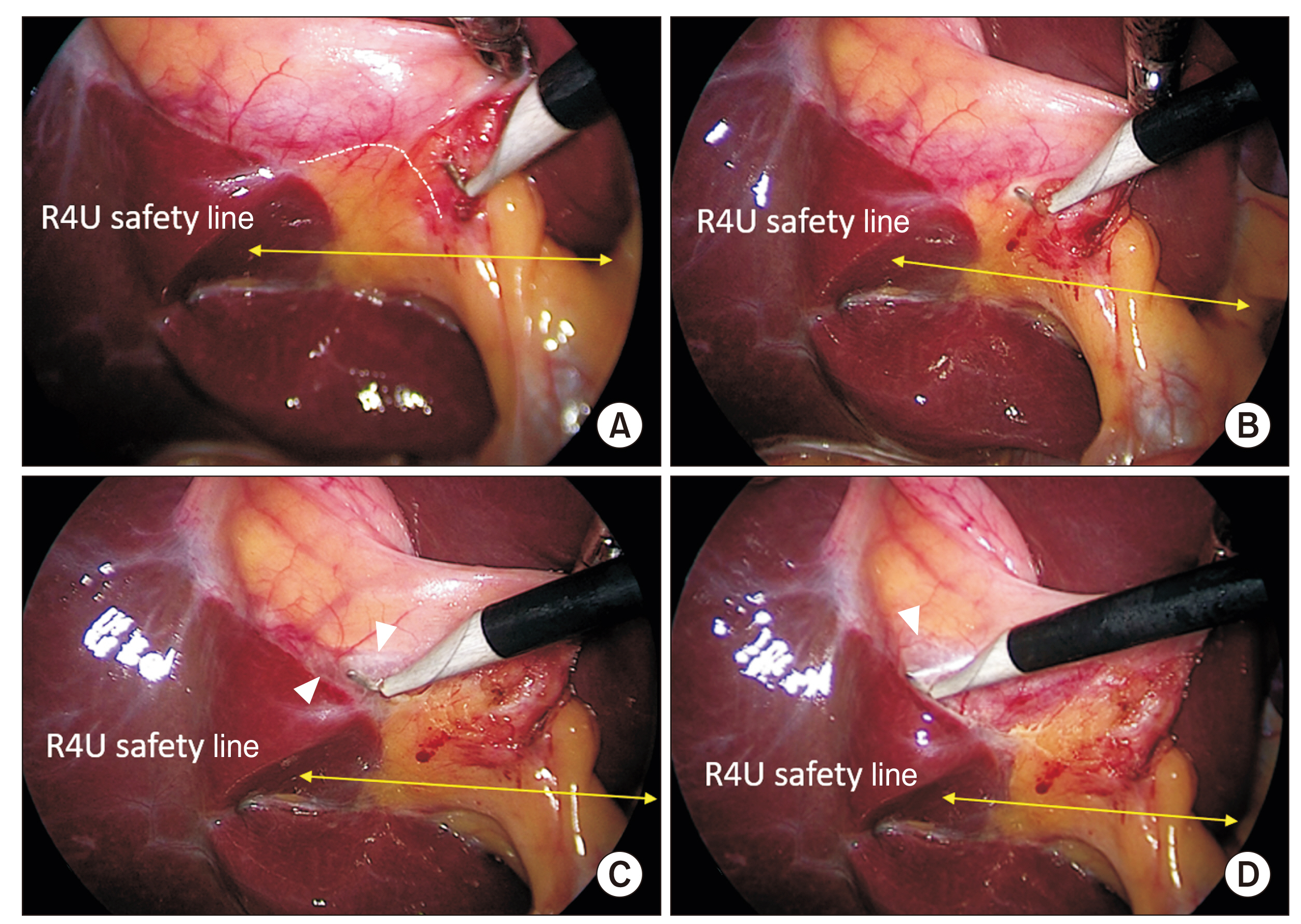

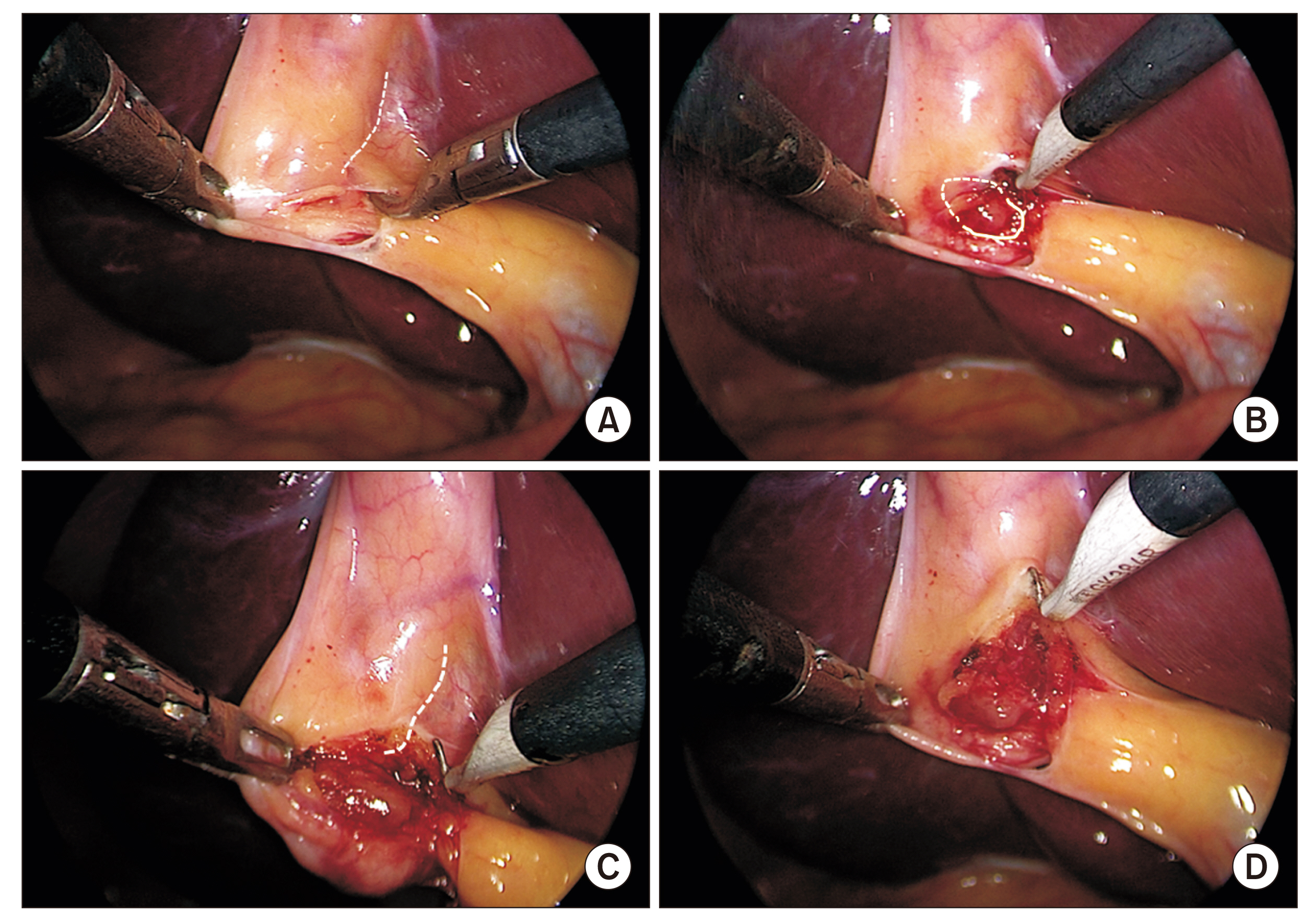

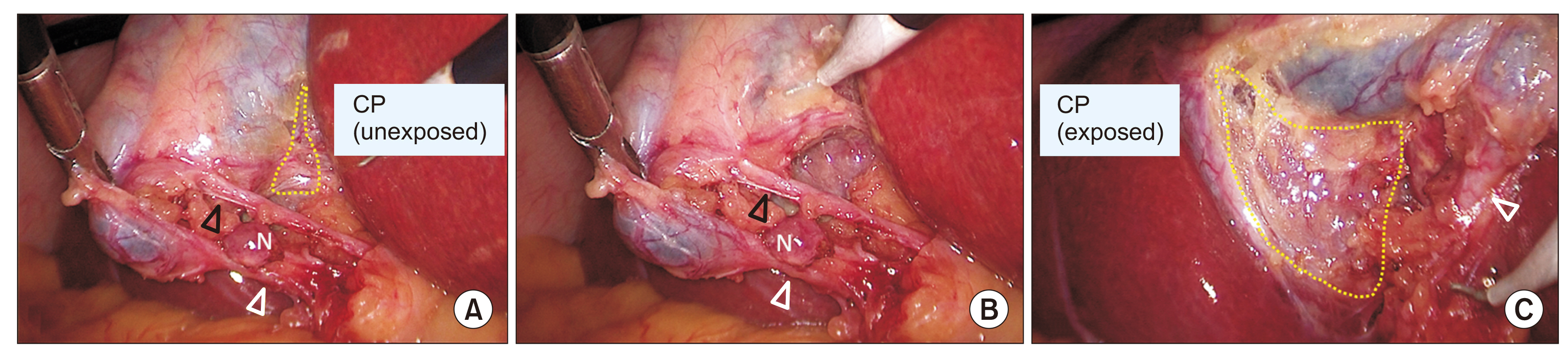

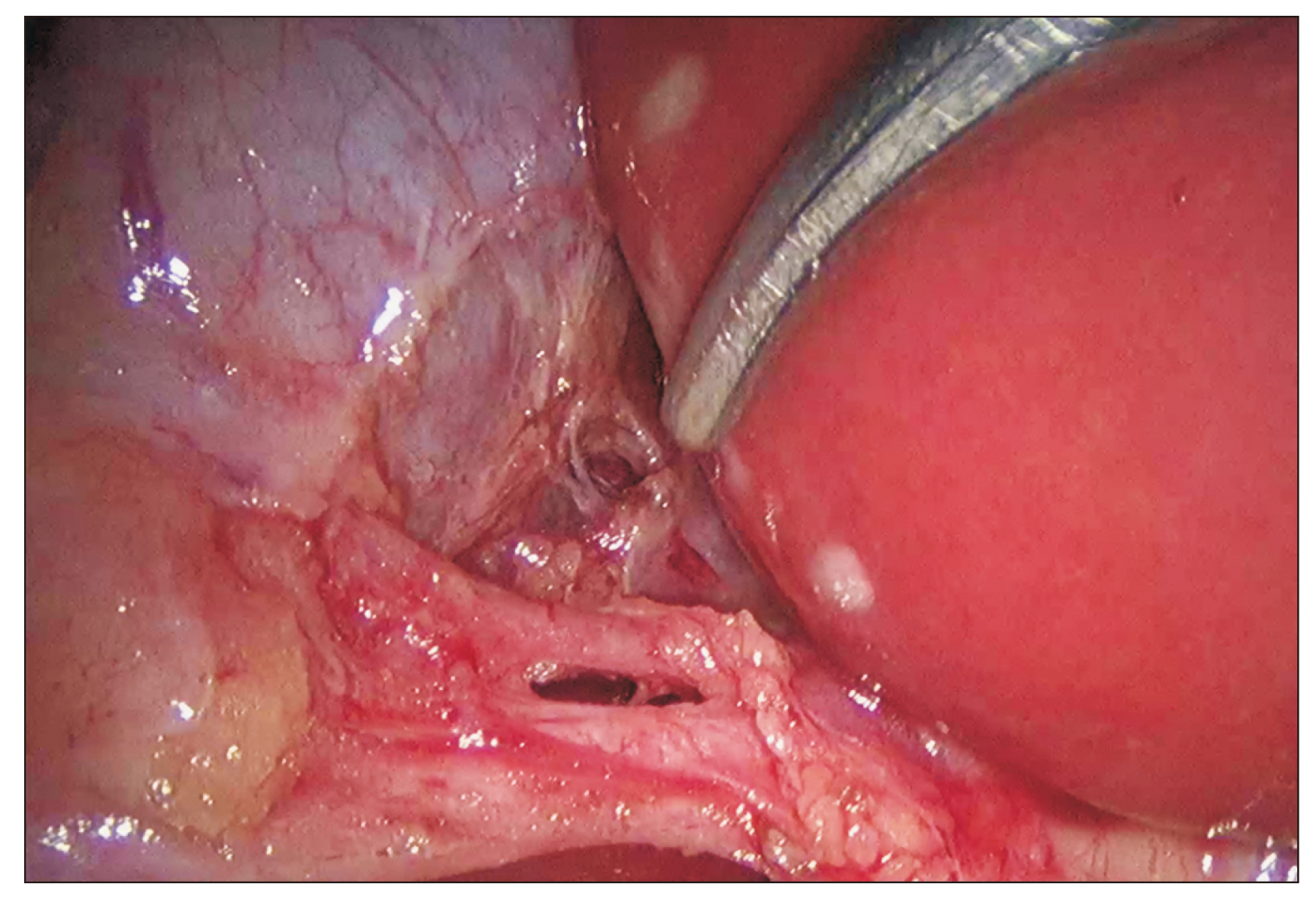

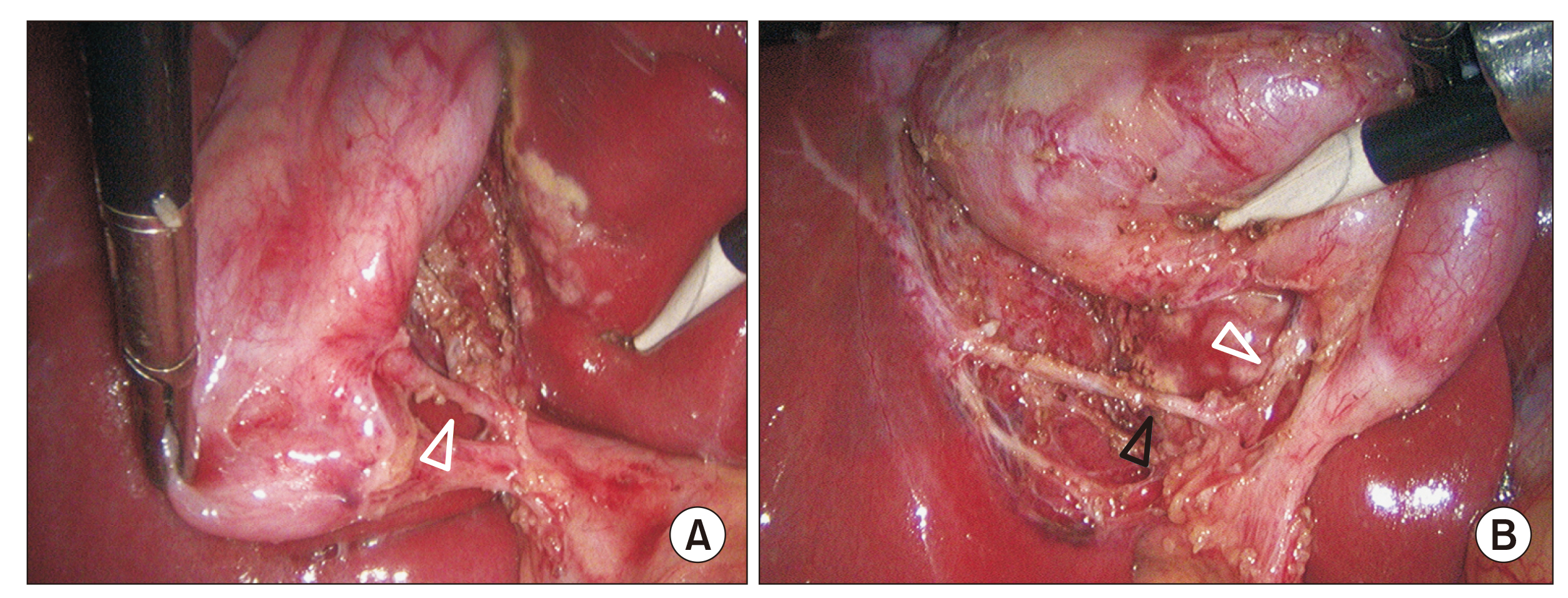

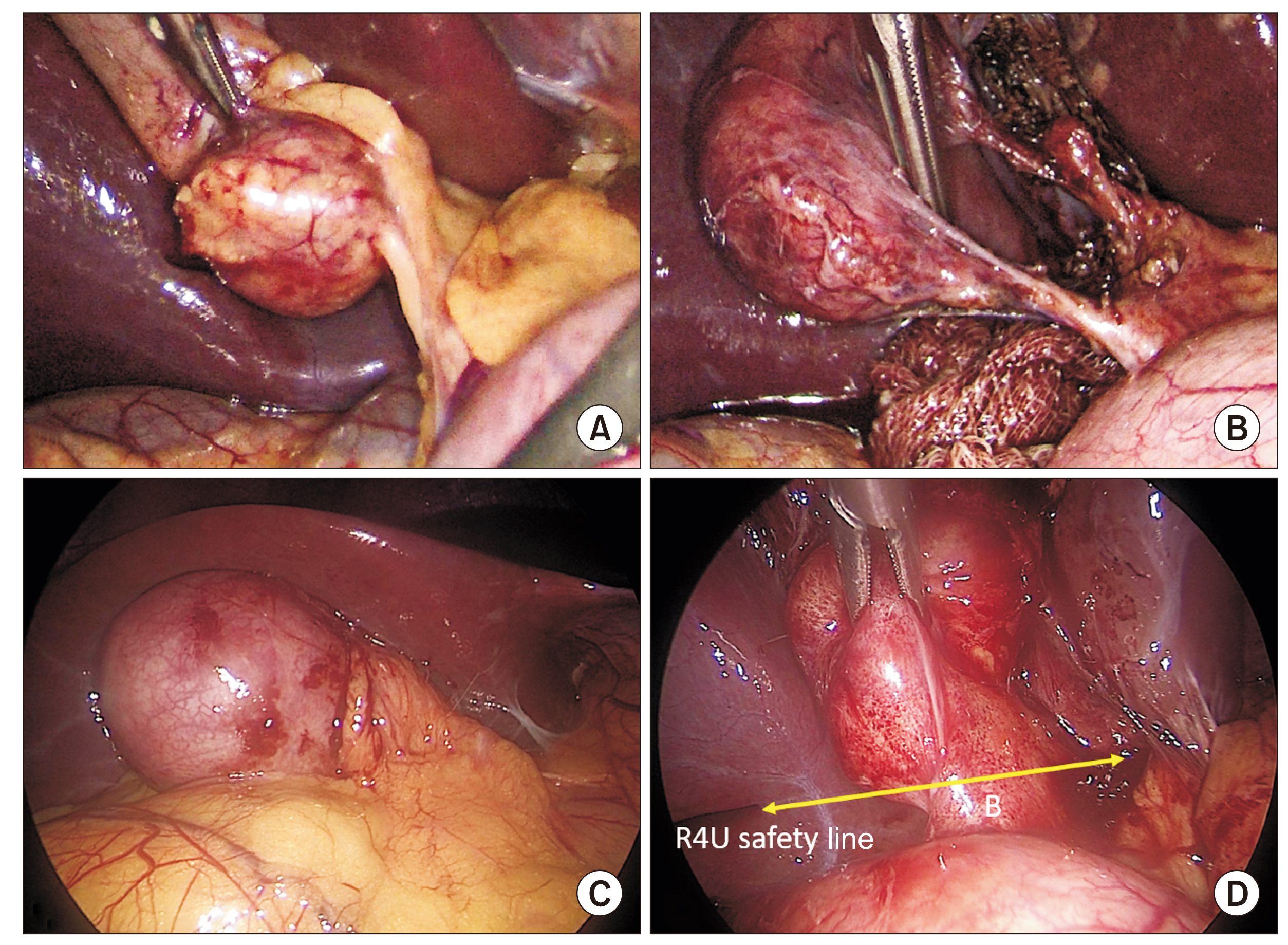

How to achieve the critical view of safety for safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Technical aspects

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India

- KMID: 2542585

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14701/ahbps.22-064

Abstract

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a higher incidence of biliary/vasculobiliary injuries than open cholecystectomy. Anatomical misperception is the most common underlying mechanism of such injuries. Although a number of strategies have been described to prevent these injuries, critical view of safety method of structural identification seems to be the most effective preventive measure. The critical view of safety can be achieved in the majority of cases during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It is highly recommended by various guidelines. However, its poor understanding and low adoption rates among practicing surgeons have been global problems. Educational intervention and increasing awareness about the critical view of safety can increase its penetration in routine surgical practice. In this article, a technique of achieving critical view of safety during laparoscopic cholecystectomy is described with the aim to enhance its understanding among general surgery trainees and practicing general surgeons.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Brunt LM, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, Strasberg SM, Aggarwal R, Asbun H, et al. 2020; Safe cholecystectomy multi-society practice guideline and state of the art consensus conference on prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 272:3–23. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003791. PMID: 32404658.

Article2. Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. 2010; Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 211:132–138. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.053. PMID: 20610259.

Article3. Strasberg SM. 2017; A perspective on the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg. 2:91. DOI: 10.21037/ales.2017.04.08.

Article4. Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Ohyama T, Umezawa A, Takada T, Strasberg SM, et al. 2017; Delphi consensus on bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an evolutionary cul-de-sac or the birth pangs of a new technical framework? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 24:591–602. DOI: 10.1002/jhbp.503. PMID: 28884962.

Article5. Strasberg SM. 2002; Avoidance of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 9:543–547. DOI: 10.1007/s005340200071. PMID: 12541037.

Article6. Way LW, Stewart L, Gantert W, Liu K, Lee CM, Whang K, et al. 2003; Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries: analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Ann Surg. 237:460–469. DOI: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000060680.92690.E9. PMID: 12677139. PMCID: PMC1514483.7. Callery MP. 2006; Avoiding biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: technical considerations. Surg Endosc. 20:1654–1658. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-006-0488-3. PMID: 17063288.

Article8. Strasberg SM. 2008; Error traps and vasculo-biliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 15:284–292. DOI: 10.1007/s00534-007-1267-9. PMID: 18535766.

Article9. Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). The SAGES safe cholecystectomy program [Internet]. Available from: https://www.sages.org/safe-cholecystectomy-program/. SAGES;cited 2022 Jul 31.10. Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. 1995; An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 180:101–125.11. Pucher PH, Brunt LM, Fanelli RD, Asbun HJ, Aggarwal R. 2015; SAGES expert Delphi consensus: critical factors for safe surgical practice in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 29:3074–3085. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-015-4079-z. PMID: 25669635.

Article12. Conrad C, Wakabayashi G, Asbun HJ, Dallemagne B, Demartines N, Diana M, et al. 2017; IRCAD recommendation on safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 24:603–615. DOI: 10.1002/jhbp.491. PMID: 29076265.

Article13. Wakabayashi G, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: surgical management of acute cholecystitis: safe steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018; 25:73–86. DOI: 10.1002/jhbp.517. PMID: 29095575.14. Eikermann M, Siegel R, Broeders I, Dziri C, Fingerhut A, Gutt C, et al. 2012; Prevention and treatment of bile duct injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the clinical practice guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc. 26:3003–3039. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-012-2511-1. PMID: 23052493.

Article15. Bansal VK, Misra M, Agarwal AK, Agrawal JB, Agarwal PN, Aggarwal S, et al. 2021; SELSI consensus statement for safe cholecystectomy - prevention and management of bile duct injury - Part A. Indian J Surg. 83(Suppl 3):592–610. DOI: 10.1007/s12262-019-01993-2.

Article16. Nijssen MA, Schreinemakers JM, Meyer Z, van der Schelling GP, Crolla RM, Rijken AM. 2015; Complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a video evaluation study of whether the critical view of safety was reached. World J Surg. 39:1798–1803. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-015-2993-9. PMID: 25711485.

Article17. Daly SC, Deziel DJ, Li X, Thaqi M, Millikan KW, Myers JA, et al. 2016; Current practices in biliary surgery: do we practice what we teach? Surg Endosc. 30:3345–3350. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-015-4609-8. PMID: 26541721.

Article18. van de Graaf FW, van den Bos J, Stassen LPS, Lange JF. 2018; Lacunar implementation of the critical view of safety technique for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a nationwide survey. Surgery. 164:31–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.01.016. PMID: 29525733.

Article19. Jin Y, Liu R, Chen Y, Liu J, Zhao Y, Wei A, et al. 2022; Critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective investigation from both cognitive and executive aspects. Front Surg. 9:946917. DOI: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.946917. PMID: 35978606. PMCID: PMC9377448.

Article20. Alanis-Rivera B, Rangel-Olvera G. 2022; Evaluation of the knowledge of the critical view of safety and recognition of the transoperative complexity during the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 36:8408–8414. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-022-09120-1. PMID: 35233656.

Article21. Gupta V, Lal P, Vindal A, Singh R, Kapoor VK. 2021; Knowledge of the culture of safety in cholecystectomy (COSIC) among surgical residents: do we train them well for future practice? World J Surg. 45:971–980. Erratum in: World J Surg 2021;45:1602. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-020-05911-6. PMID: 33454794.

Article22. Nakazato T, Su B, Novak S, Deal SB, Kuchta K, Ujiki M. 2020; Improving attainment of the critical view of safety during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 34:4115–4123. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-019-07178-y. PMID: 31605213.

Article23. Gupta V, Jain G. 2019; Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: adoption of universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg. 11:62–84. DOI: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i2.62. PMID: 30842813. PMCID: PMC6397793.

Article24. Gupta V, Jain G. 2021; The R4U planes for the zonal demarcation for safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 45:1096–1101. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-020-05908-1. PMID: 33491141.

Article25. Sanford DE, Strasberg SM. 2014; A simple effective method for generation of a permanent record of the Critical View of Safety during laparoscopic cholecystectomy by intraoperative "doublet" photography. J Am Coll Surg. 218:170–178. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.11.003. PMID: 24440064.

Article26. Andall RG, Matusz P, du Plessis M, Ward R, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. 2016; The clinical anatomy of cystic artery variations: a review of over 9800 cases. Surg Radiol Anat. 38:529–539. DOI: 10.1007/s00276-015-1600-y. PMID: 26698600.

Article27. Gupta V. 2020; Vanishing Calot syndrome: common face of many problems. J Am Coll Surg. 231:187–188. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.002. PMID: 32389576.

Article28. Nassar AHM, Ng HJ, Wysocki AP, Khan KS, Gil IC. 2021; Achieving the critical view of safety in the difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study of predictors of failure. Surg Endosc. 35:6039–6047. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-020-08093-3. PMID: 33067645. PMCID: PMC8523408.

Article29. Mascagni P, Rodríguez-Luna MR, Urade T, Felli E, Pessaux P, Mutter D, et al. 2021; Intraoperative time-out to promote the implementation of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a video-based assessment of 343 procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 233:497–505. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.06.018. PMID: 34325017.

Article30. Strasberg SM. 2019; A three-step conceptual roadmap for avoiding bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an invited perspective review. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 26:123–127. DOI: 10.1002/jhbp.616. PMID: 30828991.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Importance of critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a survey of 120 serial patients, with no incidence of complications

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in the Second Trimester of Pregnancy

- Rouviere’s Sulcus: A Guide to Safe Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

- What is the Safe Training to Educate the Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Surgical Residents in Early Learning Curve?

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a case of situs inversus totalis: a review of technical challenges and adaptations