J Pathol Transl Med.

2023 May;57(3):139-146. 10.4132/jptm.2023.04.25.

Trouble-makers in cytologic interpretation of the uterine cervix

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pathology, Yongin Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Yongin, Korea

- KMID: 2542280

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4132/jptm.2023.04.25

Abstract

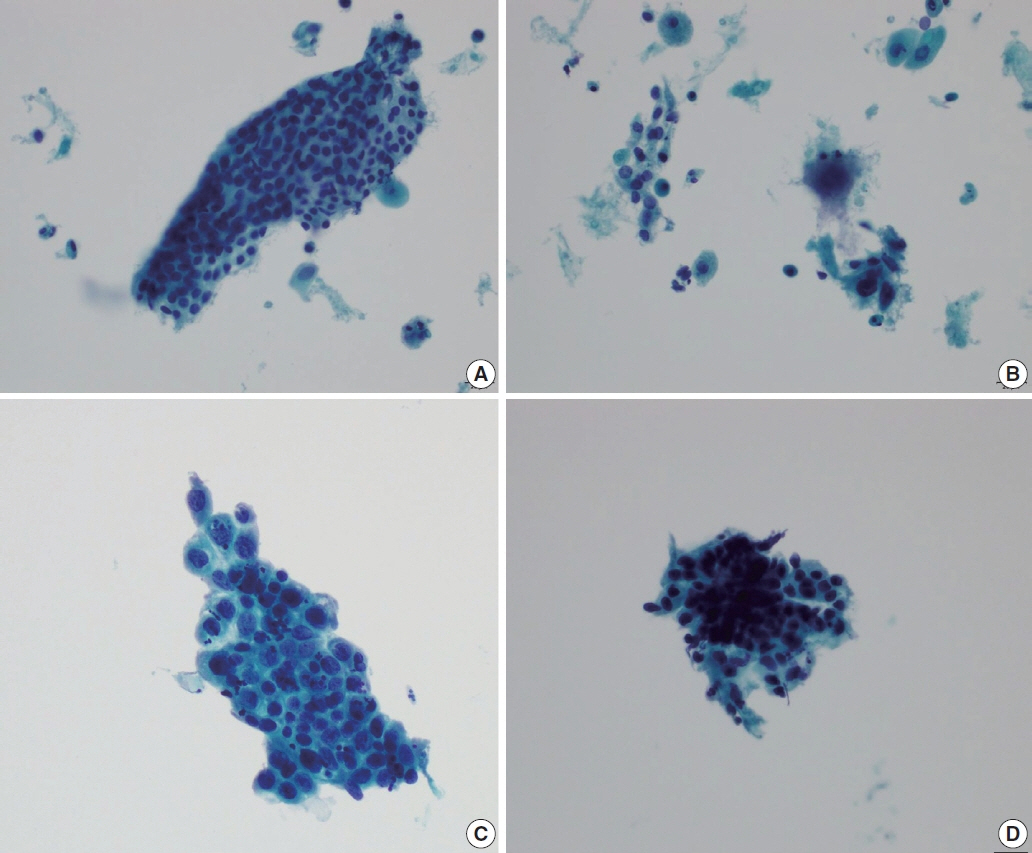

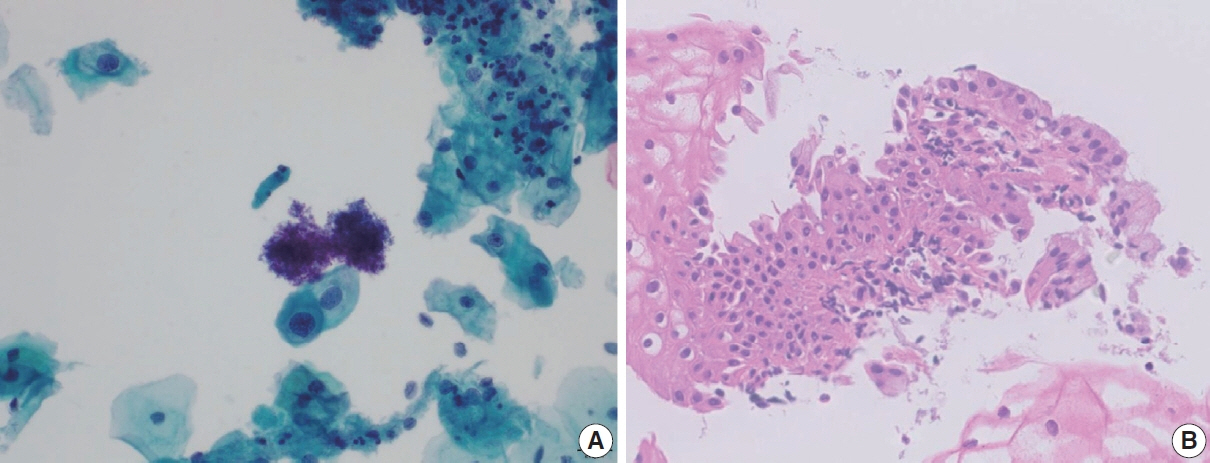

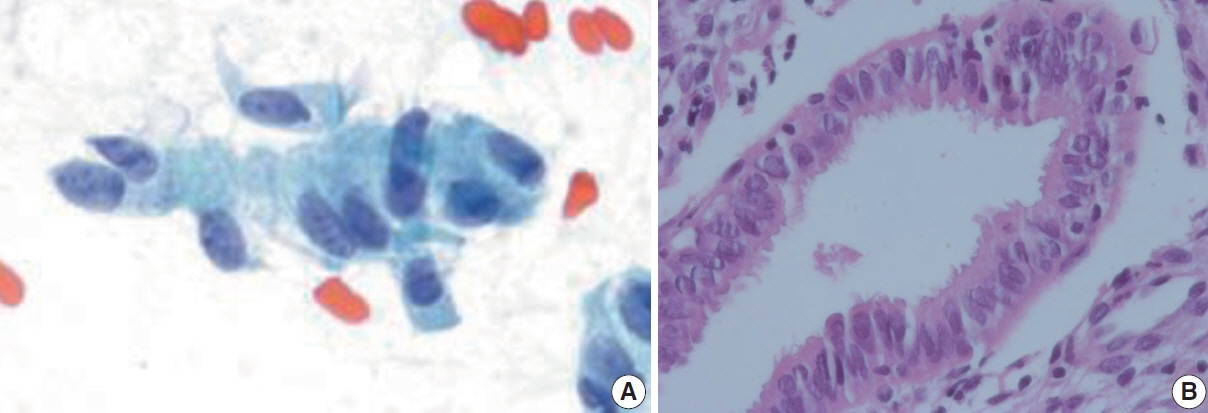

- The development and standardization of cytologic screening of the uterine cervix has dramatically decreased the prevalence of squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Advances in the understanding of biology of human papillomavirus have contributed to upgrading the histologic diagnosis of the uterine cervix; however, cytologic screening that should triage those that need further management still poses several difficulties in interpretation. Cytologic features of high grade intraepithelial squamous lesion (HSIL) mimics including atrophy, immature metaplasia, and transitional metaplasia, and glandular lesion masquerades including tubal metaplasia and HSIL with glandular involvement are described with accentuation mainly on the differential points. When the cytologic features lie in a gray zone between the differentials, the most important key to the more accurate interpretation is sticking to the very basics of cytology; screening the background and cellular architecture, and then scrutinizing the nuclear and cytoplasmic details.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Acs G, Gupta PK, Baloch ZW. Glandular and squamous atypia and intraepithelial lesions in atrophic cervicovaginal smears: one institution’s experience. Acta Cytol. 2000; 44:611–7.2. Kaminski PF, Sorosky JI, Wheelock JB, Stevens CW Jr. The significance of atypical cervical cytology in an older population. Obstet Gynecol. 1989; 73:13–5.3. Waddell CA. The influence of the cervix on smear quality. I: Atrophy. An audit of cervical smears taken post-colposcopic management of intraepithelial neoplasia. Cytopathology. 1997; 8:274–81.

Article4. Chivukula M, Shidham VB. ASC-H in Pap test: definitive categorization of cytomorphological spectrum. Cytojournal. 2006; 3:14.5. Mokhtar GA, Delatour NL, Assiri AH, Gilliatt MA, Senterman M, Islam S. Atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion: cytohistologic correlation study with diagnostic pitfalls. Acta Cytol. 2008; 52:169–77.6. Rader AE, Rose PG, Rodriguez M, Mansbacher S, Pitlik D, Abdul-Karim FW. Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance in women over 55: comparison with the general population and implications for management. Acta Cytol. 1999; 43:357–62.7. McHugh KE, Reynolds JP, Suarez AA. Postmenopausal squamous atypia: cytologic features, hybrid capture 2 tests and contribution to the ASCUS pool. Acta Cytol. 2018; 62:418–22.

Article8. Ejersbo D, Jensen HA, Holund B. Efficacy of Ki-67 antigen staining in Papanicolaou (Pap) smears in post-menopausal women with atypia: an audit. Cytopathology. 1999; 10:369–74.9. Abati A, Jaffurs W, Wilder AM. Squamous atypia in the atrophic cervical vaginal smear: a new look at an old problem. Cancer. 1998; 84:218–25.

Article10. Voytek TM, Kannan V, Kline TS. Atypical parakeratosis: a marker of dysplasia? Diagn Cytopathol. 1996; 15:288–91.

Article11. Nuovo GJ, Cottral S, Richart RM. Occult human papillomavirus infection of the uterine cervix in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989; 160:340–4.

Article12. Yakoushina TV, Medina IM, Hoda RS. “String of pearls” appearance of blue blobs in postmenopausal atrophy on ThinPrep Pap test. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009; 37:738–9.

Article13. Abdulla M, Hombal S, Kanbour A, et al. Characterizing “blue blobs”. Immunohistochemical staining and ultrastructural study. Acta Cytol. 2000; 44:547–50.14. Sheils LA, Wilbur DC. Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: stratification of the risk of association with, or progression to, squamous intraepithelial lesions based on morphologic subcategorization. Acta Cytol. 1997; 41:1065–72.15. Duggan MA. Cytologic and histologic diagnosis and significance of controversial squamous lesions of the uterine cervix. Mod Pathol. 2000; 13:252–60.

Article16. Selvaggi SM, Haefner HK. Microglandular endocervical hyperplasia and tubal metaplasia: pitfalls in the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma on cervical smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 1997; 16:168–73.

Article17. Torous VF, Pitman MB. Interpretation pitfalls and malignant mimics in cervical cytology. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2021; 10:115–27.

Article18. Chaump M, Pirog EC, Panico VJ, d Meritens AB, Holcomb K, Hoda R. Detection of in situ and invasive endocervical adenocarcinoma on ThinPrep Pap Test: morphologic analysis of false negative cases. Cytojournal. 2016; 13:28.

Article19. Khan MY, Bandyopadhyay S, Alrajjal A, Choudhury MS, Ali-Fehmi R, Shidham VB. Atypical glandular cells (AGC): cytology of glandular lesions of the uterine cervix. Cytojournal. 2022; 19:31.

Article20. Lee KR, Manna EA, St John T. Atypical endocervical glandular cells: accuracy of cytologic diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995; 13:202–8.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Cytologic features of glassy cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix

- Cytologic Features of Villoglandular Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Cervix : A Report of Two Cases

- Cytologic Features of Malignant Lymphoma of the Uterine Cervix: A case report

- Atypical Condyloma of Uterine Cervix: It's Cytological Similarity to Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- The Cytologic Analysis of Microinvasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix on Cervical Smear