Ewha Med J.

2023 Apr;46(2):e3. 10.12771/emj.2023.e3.

A Rare Case of Methotrexate Induced Pancreatitis in Ectopic Pregnancy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2542122

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12771/emj.2023.e3

Abstract

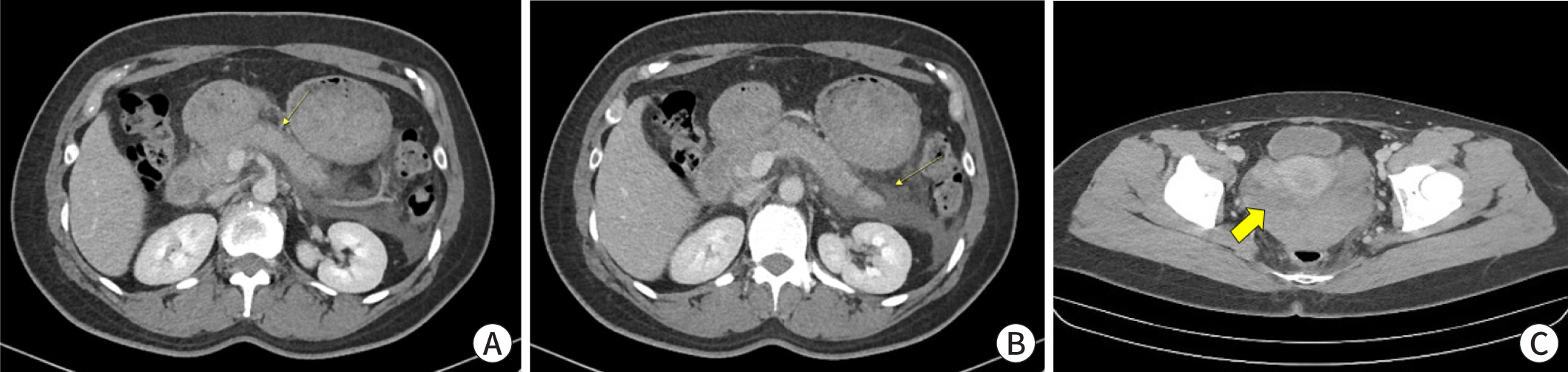

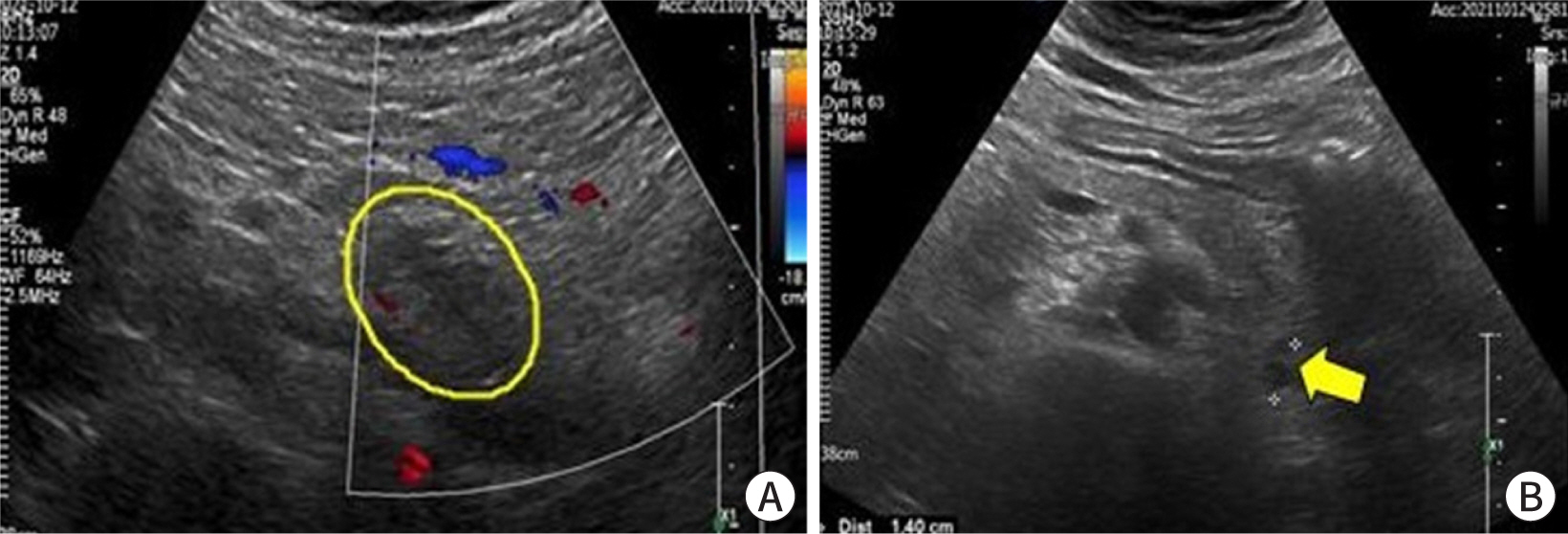

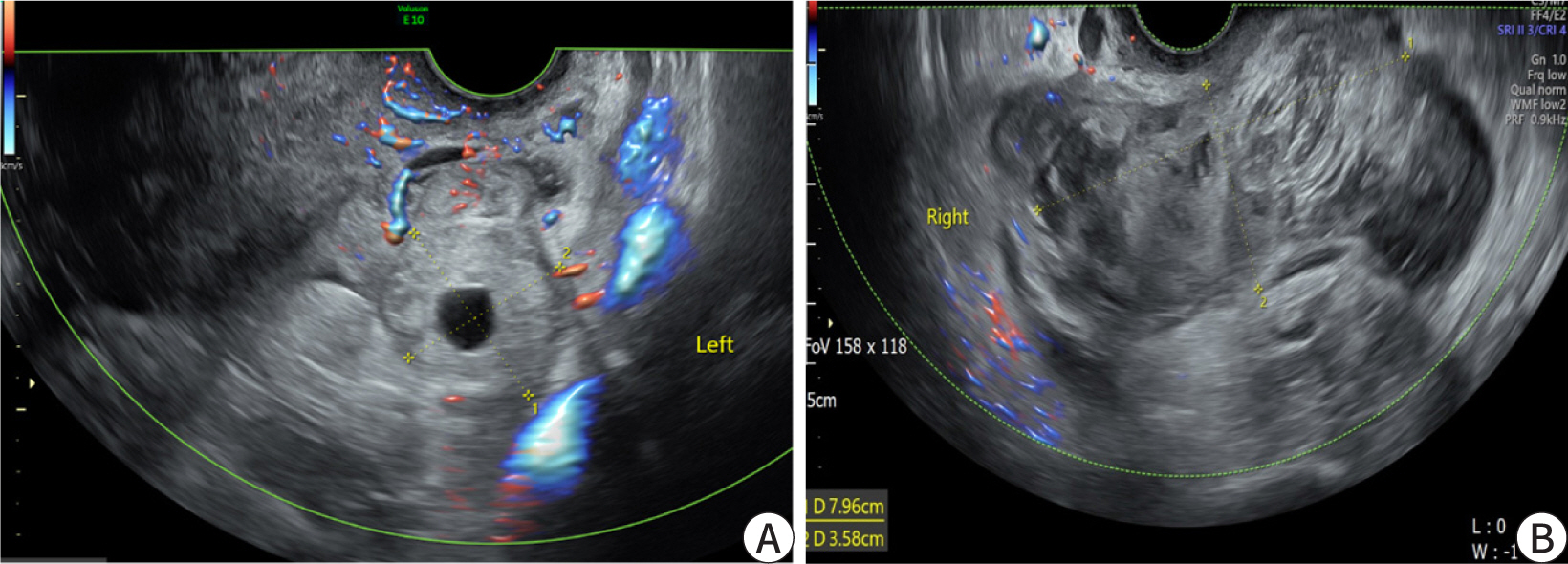

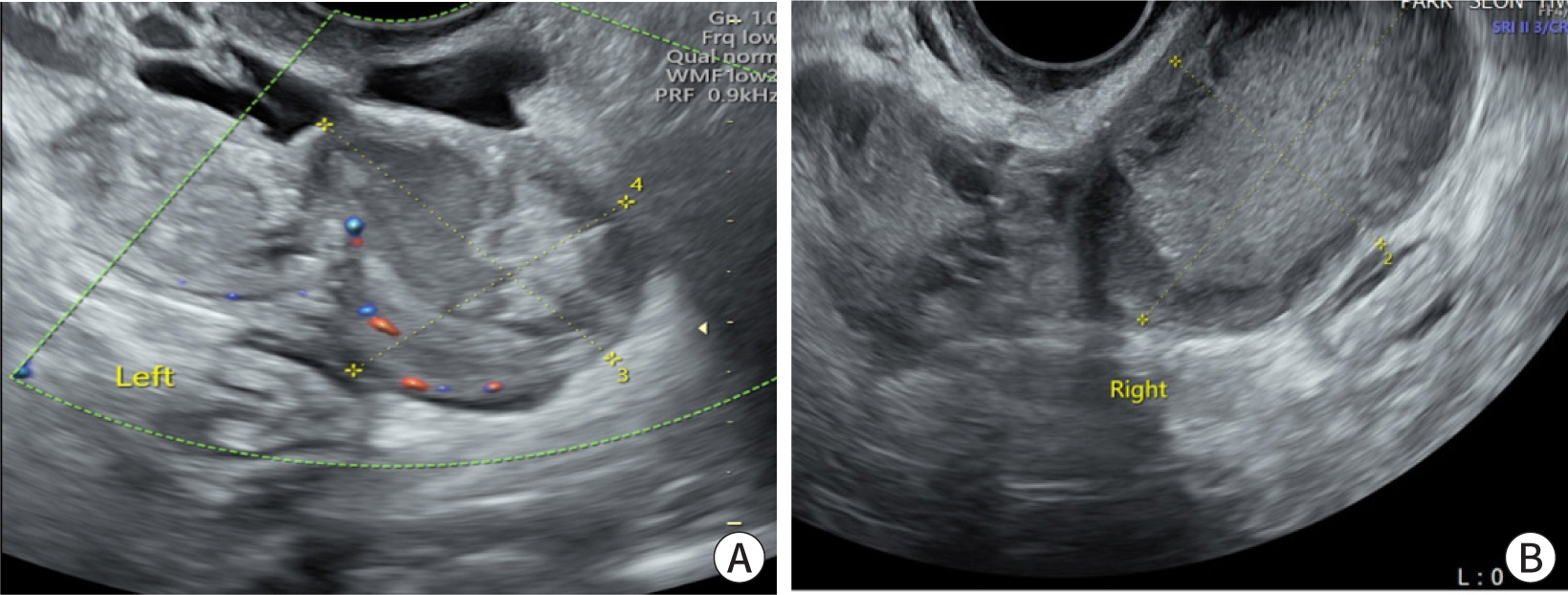

- Ectopic pregnancy (EP) refers to blastocyst implantation outside the uterine endometrium. EP is major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Treatment options include surgery, medical therapy with methotrexate, or expectant management. Methotrexate is the primary regimen used in cases of early, unruptured ectopic pregnancies. Most side effects of methotrexate are minor, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and photosensitive skin reaction. Serious side effects, including bone marrow suppression, and pulmonary fibrosis, are invariably observed when methotrexate is administered in high doses with frequent dosing intervals, in chemotherapeutic protocols for malignancy. These side effects are uncommon with the doses used to treat ectopic pregnancies. Since cases of methotrexate-induced pancreatitis are rare, we report a case of pancreatitis in a patient with EP treated with methotrexate and expect to consider pancreatitis as a side effect of methotrexate in a patient with upper abdominal pain undergoing methotrexate chemotherapy.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Taran FA, Kagan KO, Hübner M, Hoopmann M, Wallwiener D, Bruker S. The diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015; 112((41)):693–703. DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0693. PMID: 26554319. PMCID: PMC4643163.2. Chow WH, Daling JR, Cates W JR, Greenberg RS. Epidemiology of ectopic pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev. 1987; 9((1)):70–94. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036309. PMID: 3315720.3. Lipscomb GH. Medical management of ectopic pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012; 55((2)):424–432. DOI: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182510a48. PMID: 22510624.4. Barnhart K, Coutifaris C, Esposito M. The pharmacology of methotrexate. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005; 2((3)):409–417. DOI: 10.1517/14656566.2.3.409. PMID: 11336595.5. Bleyer WA. The clinical pharmacology of methotrexate: new applications of an old drug. Cancer. 1978; 41((1)):36–51. DOI: 10.1002/1097-0142(197801)41:1<36::AID-CNCR2820410108>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID: 342086.6. Kremer JM. Toward a better understanding of methotrexate. Arthrit Rhrumat. 2004; 50((5)):1370–1382. DOI: 10.1002/art.20278. PMID: 15146406.7. Condous G, Okaro E, Khalid A, Lu C, Van Huffel S, Timmerman D, et al. A prospective evaluation of a single-visit strategy to manage pregnancies of unknown location. Hum Reprod. 2005; 20((5)):1398–1403. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/deh746. PMID: 15665023.8. Stovall TG, Ling FW, Gray LA, Carson SA, Buster JE. Methotrexate treatment of unruptured ectopic pregnancy: a report of 100 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 77((5)):749–753.9. Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013; 13((4)):Se1–Se15. DOI: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.07.063.10. Toouli J, Brooke-Smith M, Bassi C, Carr-Locke D, Telford J, Freeny P, et al. Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002; 17:S15–S39. DOI: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.17.s1.2.x. PMID: 12000591.11. Zheng Z, Ding YX, Qu YX, Cao F, Li F. A narrative review of acute pancreatitis and its diagnosis, pathogenetic mechanism, and management. Ann Transl Med. 2021; 9((1)):69. DOI: 10.21037/atm-20-4802. PMID: 33553362. PMCID: PMC7859757.12. Kolk A, Horneff G, Wilgenbus KK, Wahn V, Gerharz CD. Acute lethal necrotising pancreatitis in childhood systemic lupus erythematosus--possible toxicity of immunosuppressive therapy. Clini Exp Rheumatol. 1995; 13((3)):399–403.13. Shrikiran A. A rare case of methotrextate induced pancreatitis in acute leaukemia patient. WebmedCentral Paediatrics. 2011; 2((12)):WMC002820.14. Chen CC, Wang SS, Lee FY. Action of antiproteases on the inflammatory response in acute pancreatitis. JOP J Pancreas. 2007; 8:S488–S494.15. Stovall TG, Ling FW. Single-dose methotrexate: an expanded clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 168((6)):1759–1762. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90687-E. PMID: 8317518.16. Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000; 356((9237)):1255–1259. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02799-9. PMID: 11072960.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Cervical Pregnancy Treated by Intra-ovular Injection of Methotrexate

- A Case of Cervical Pregnancy Treated by both Intraamniotic and Systemic Methotrexate Injection

- Treatment of ectopic pregnancy by the laparoscopy guided methotrexate injection

- Successful treatment with methotrexate injection on ectopic pregnancy embedded in the myometrium of a previous cesarean section scar

- Treatment of ectopic pregnancy by the laparoscopy guided methotrexate injection