J Korean Soc Matern Child Health.

2023 Jan;27(1):1-13. 10.21896/jksmch.2023.27.1.1.

Narrative Review on the Trend of Childbirth in South Korea and Feasible Intervention to Reduce Cesarean Section Rate

- Affiliations

-

- 1Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2539413

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2023.27.1.1

Abstract

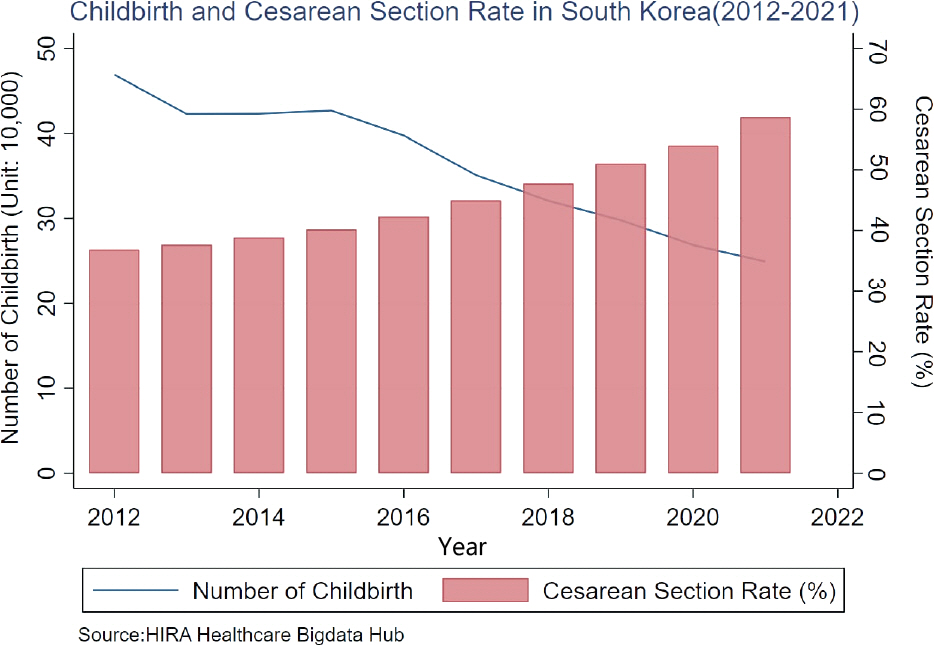

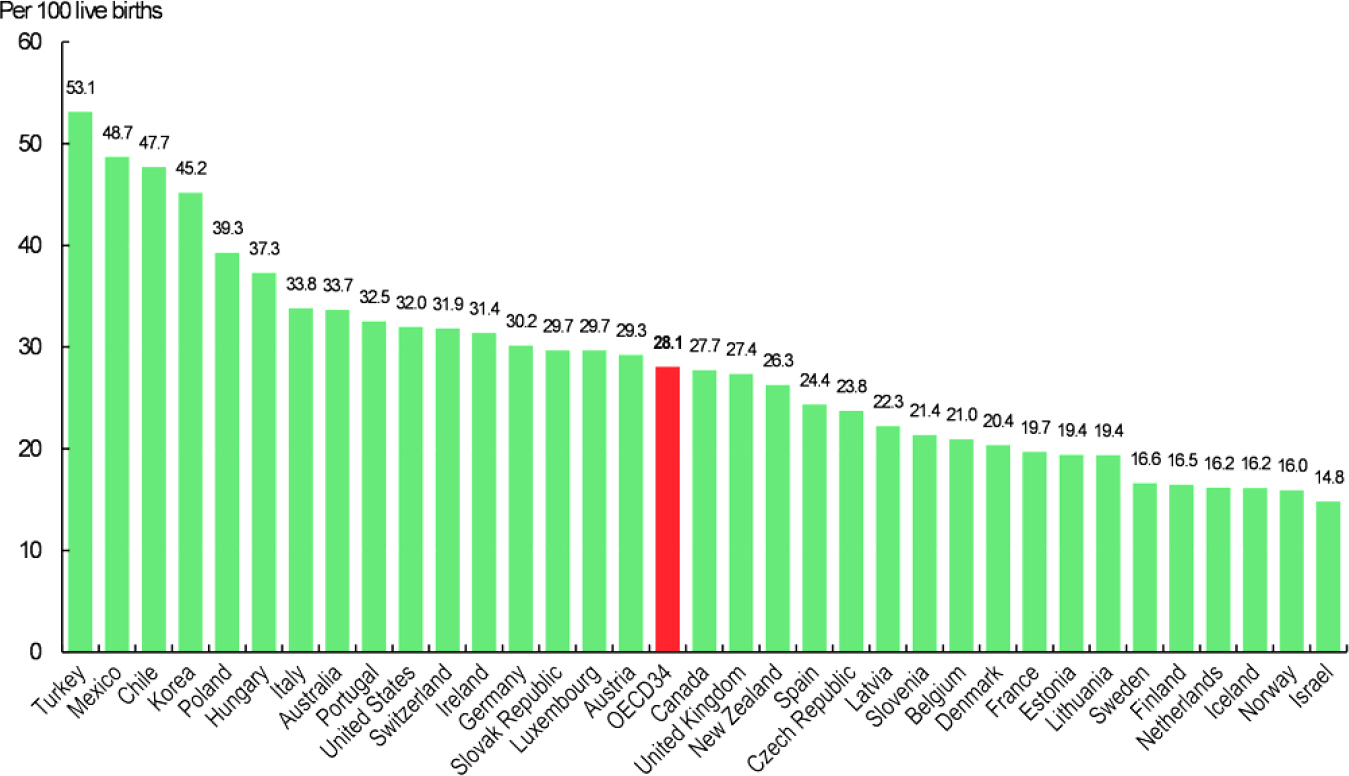

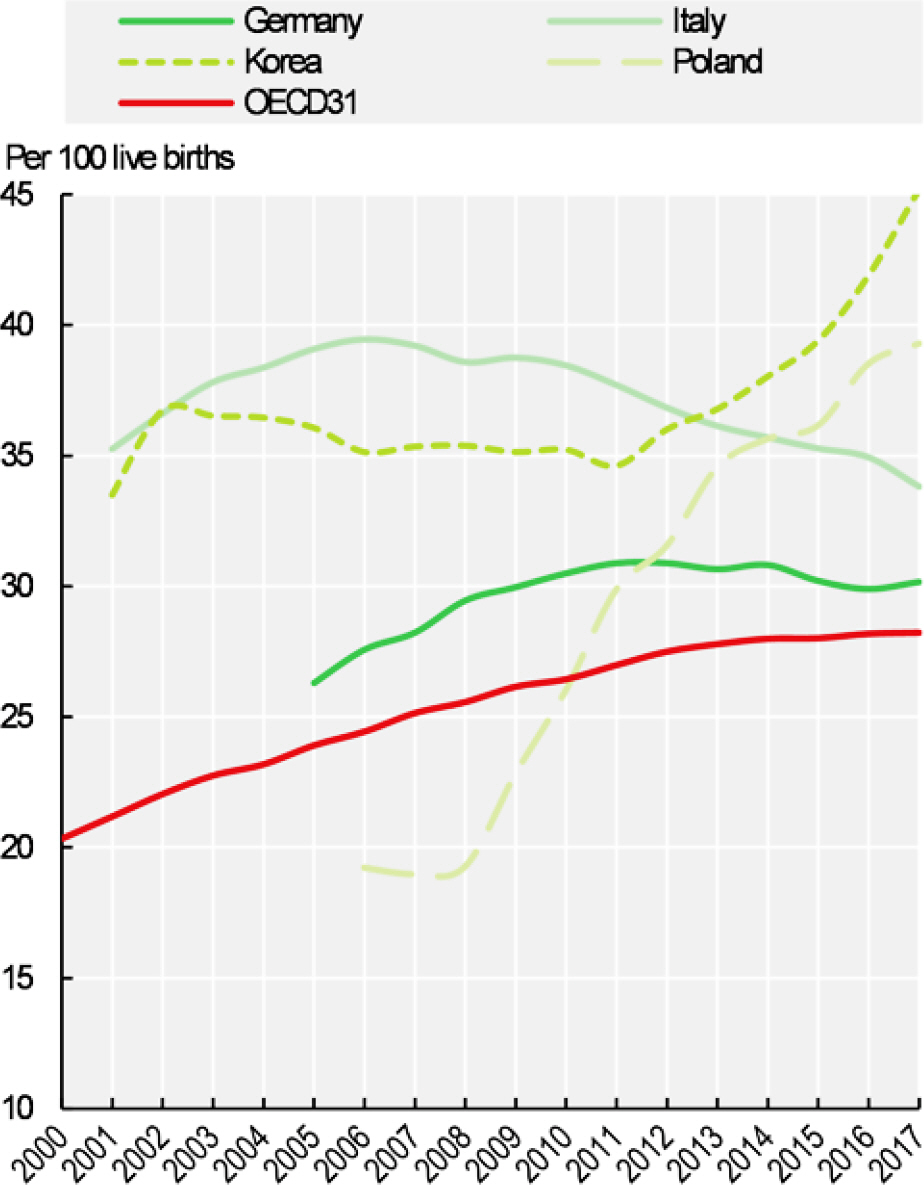

- In this study, we explored the current childbirth trend in South Korea to provide recent evidence on determinants of the cesarean section rate (CSR) and related policy interventions. We utilized national health insurance claim data to analyze the CSR. We also conducted a narrative review on factors associated with the CSR and examined evidence about interventions to reduce it. The CSR is rising in Korea; simultaneously, the overall number of births is declining. In 2012, 469,000 women gave birth, and 26.9% underwent a cesarean section. In 2021, 249,000 women gave birth, and 58.7% experienced a cesarean section. The CSR among women under age 25 was 26.7% in 2012, but by the first quarter of 2022, it was 51.6%. In 2012, the CSR in women aged 25–34 years was 34.9%; by the first quarter of 2022, it was 58.3%. We synthesized evidence on the determinants of CSR in three dimensions: users, providers, and systems. We also explored recent evidence on policy interventions to reduce the CSR, focusing on women and families, providers, and hospitals. Despite the rapid increase in the CSR in the last decade, efforts to investigate childbirth choice and women’s experiences have been insufficient. We could not locate systematic initiatives in the research community or government to lower the rate. More patient-centered efforts to reduce the high CSR rate are needed.

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Factors Affecting Married Women's Intention to Have a Second Child: Focusing on Reproductive Health Factors

Shinhwee Oh, So-Young Lee

J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2023;27(2):110-118. doi: 10.21896/jksmch.2023.27.2.110.Clinical Applications of the Microbiome in Obstetrics

Seung Yeon Pyeon, Da Young Kang, So Young Kim, Sun Woo Choi, Moon Yeon Hwang, Young Joo Lee

Neonatal Med. 2023;30(4):89-95. doi: 10.5385/nm.2023.30.4.89.Preparation of the nursing workforce in the field of women’s health

Sukhee Ahn

Womens Health Nurs. 2024;30(2):91-95. doi: 10.4069/whn.2024.05.30.

Reference

-

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Com-mittee Opinion No. 394, December 2007. Cesarean delivery on maternal request. Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 110:1501.Azimirad A. Cesarean section beyond cesar's borders: a mini review on the cultural history of cesarean section high prevalence rates in the Middle East. Arch Iran Med. 2020. 23:335–7.Bertoli P., Grembi V., Llaneza Hesse C., Vall Castelló J. The effect of budget cuts on C-section rates and birth outcomes: Evidence from Spain. Soc Sci Med. 2020. 265:113419.Betran AP., Ye J., Moller AB., Souza JP., Zhang J. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021. 6:e005671.Black M., Bhattacharya S. Cesarean section in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong-A safe choice for women and clinicians? PLoS Med. 2018. 15:e1002676.Burns LR., Geller SE., Wholey DR. The effect of physician factors on the cesarean section decision. Med Care. 1995. 33:365–82.Caughey AB., Cahill AG., Guise JM., Rouse DJ. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College); Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014. 210:179–93.Chaillet N., Dumont A., Abrahamowicz M., Pasquier JC., Audibert F., Monnier P, et al. A cluster-randomized trial to reduce cesarean delivery rates in Quebec. N Engl J Med. 2015. 372:1710–21.Chen I., Opiyo N., Tavender E., Mortazhejri S., Rader T., Petkovic J, et al. Non-clinical interventions for reducing unnecessary caesarean section. Co chrane Database Syst Rev. 2018. 9:CD005528.Cho DB. Identifying current state of medical malpractice in obstetric department and causes of medical malpractice through an analysis of court decisions on medical disputes [Doctoral thesis]. Seoul (Korea): Yonsei University;2015. Available from: https://ir.ymlib.yonsei.ac.kr/handle/22282913/146192.Cho YM., Kim YM. Gender ideology and fertility intentions amid the changing breadwinner model: a mixed method approach. Korea J Popul Stud. 2020. 43:69–97. https://doi.org/10.31693/KJPS.2020.12.43.4.69.Chung SH., Seol HJ., Choi YS., Oh SY., Kim A., Bae CW. Changes in the cesarean section rate in Korea (1982-2012) and a review of the associated factors. J Korean Med Sci. 2014. 29:1341–52.Deneux-Tharaux C., Carmona E., Bouvier-Colle MH., Bréart G. Post-partum maternal mortality and cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 108(3 Pt 1):541–8.Epstein AJ., Nicholson S. The formation and evolution of physician treatment styles: an application to cesarean sections. J Health Econ. 2009. 28:1126–40.Escobal APL., Andrade APM., Matos GC., Giusti PH., Cecagno S., Prates LA. Relationship between power and knowledge in choosing a cesarean section: women's perspectives. Rev Bras Enferm. 2021. 75:e20201389.Facchini G. Low staffing in the maternity ward: keep calm and call the surgeon. J Econ Behav Organ. 2022. 197:370–94.Faúndes A., Pádua KS., Osis MJ., Cecatti JG., Sousa MH. Brazilian women and physicians' viewpoints on their preferred route of delivery. Rev Saude Publica. 2004. 38:488–94. Portuguese.Geller EJ., Wu JM., Jannelli ML., Nguyen TV., Visco AG. Maternal outcomes associated with planned vaginal versus planned primary cesarean delivery. Am J Perinatol. 2010. 27:675–83.Habiba M., Kaminski M., Da Frè M., Marsal K., Bleker O., Librero J, et al. Caesarean section on request: a comparison of obstetricians' attitudes in eight European countries. BJOG. 2006. 113:647–56.Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Results of the 2012 C-section adequacy assessment [Internet]. Wonju (Korea): Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service;2012. [cited 2022 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.hira.or.kr/cms/open/04/04/12/2012_12.pdf.Hoxha I., Sadiku F., Lama A., Bunjaku G., Agahi R., Statovci J, et al. Cesarean delivery and gender of delivering physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2020. 136:1170–8.Hoxha I., Syrogiannouli L., Luta X., Tal K., Goodman DC., da Costa BR, et al. Caesarean sections and for-profit status of hospitals: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017. 7:e013670.Jenabi E., Khazaei S., Bashirian S., Aghababaei S., Matinnia N. Reasons for elective cesarean section on maternal request: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020. 33:3867–72.Karlström A., Lindgren H., Hildingsson I. Maternal and infant outcome after caesarean section without recorded medical indication: findings from a Swedish case-control study. BJOG. 2013. 120:479–86.Keag OE., Norman JE., Stock SJ. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018. 15:e1002494.Keeler EB., Brodie M. Economic incentives in the choice between vaginal delivery and cesarean section. Milbank Q. 1993. 71:365–404.Khang YH., Yun SC., Jo MW., Lee MS., Lee SI. Public release of institutional Cesarean section rates in South Korea: which women were aware of the information? Health Policy. 2008. 86:10–6.Kim AM., Park JH., Kang S., Yoon TH., Kim Y. An ecological study of geographic variation and factors associated with cesarean section rates in South Korea. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019. 19:162.Kim HY., Lee D., Kim J., Noh E., Ahn KH., Hong SC, et al. Secular trends in cesarean sections and risk factors in South Korea (2006-2015). Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2020. 63:440–7.Lee AS., Kirkman M. Disciplinary discourses: rates of cesarean section explained by medicine, midwifery, and feminism. Health Care Women Int. 2008. 29:448–67.Lee SI., Khang YH., Lee MS. Women's attitudes toward mode of delivery in South Korea–a society with high cesarean section rates. Birth. 2004. 31:108–16.Li HT., Zhou YB., Liu JM. The impact of cesarean section on offspring overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013. 37:893–9.Liu S., Liston RM., Joseph KS., Heaman M., Sauve R., Kramer MS, et al. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. CMAJ. 2007. 176:455–60.Localio AR., Lawthers AG., Bengtson JM., Hebert LE., Weaver SL., Brennan TA, et al. Relationship between malpractice claims and cesarean delivery. JAMA. 1993. 269:366–73.Loke AY., Davies L., Mak YW. Is it the decision of women to choose a cesarean section as the mode of birth? A review of literature on the views of stakeholders. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019. 19:286.Maeda E., Ishihara O., Tomio J., Sato A., Terada Y., Kobayashi Y, et al. Cesarean section rates and local resources for perinatal care in Japan: a nationwide ecological study using the national database of health insurance claims. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018. 44:208–16.Mascarello KC., Horta BL., Silveira MF. Maternal complications and cesarean section without indication: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Saude Publica. 2017. 51:105.McCourt C., Weaver J., Statham H., Beake S., Gamble J., Creedy DK. Elective cesarean section and decision making: a critical review of the literature. Birth. 2007. 34:65–79.McGrath SK., Kennell JH. A randomized controlled trial of continuous labor support for middle-class couples: effect on cesarean delivery rates. Birth. 2008. 35:92–7.Mitler LK., Rizzo JA., Horwitz SM. Physician gender and cesarean sections. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000. 53:1030–5.Molina G., Weiser TG., Lipsitz SR., Esquivel MM., Uribe-Leitz T., Azad T, et al. Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015. 314:2263–70.Mossialos E., Allin S., Karras K., Davaki K. An investigation of Caesarean sections in three Greek hospitals: the impact of financial incentives and convenience. Eur J Public Health. 2005. 15:288–95.Mu Y., Li X., Zhu J., Liu Z., Li M., Deng K, et al. Prior caesarean section and likelihood of vaginal birth, 2012-2016, China. Bull World Health Organ. 2018. 96:548–57.O'Donovan C., O'Donovan J. Why do women request an elective Cesarean delivery for non-medical reasons? A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Birth. 2018. 45:109–19.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Geographic variations in health care: what do we know and what can be done to improve health system performance? Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development;2014.Park Y., Kim JH., Lee KS. Changes in cesarean section rate before and after the end of the Korean Value Incentive Program. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022. 101:e29952.Penna L., Arulkumaran S. Cesarean section for non-medical reasons. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003. 82:399–409.Ryding EL., Lukasse M., Kristjansdottir H., Steingrimsdottir T., Schei B; Bidens study group. Pregnant women's preference for cesarean section and subsequent mode of birth - a six-country cohort study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2016. 37:75–83.Sandall J., Tribe RM., Avery L., Mola G., Visser GH., Homer CS, et al. Short-term and long-term effects of caesarean section on the health of women and children. Lancet. 2018. 392:1349–57.Schei B., Lukasse M., Ryding EL., Campbell J., Karro H., Kristjansdottir H, et al. A history of abuse and operative delivery–results from a European multi-country cohort study. PLoS One. 2014. 9:e87579.Sewell JE. Cesarean section - a brief history [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine;1993. [cited 2022 May 12]. Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/cesarean/index.html.Shirzad M., Shakibazadeh E., Hajimiri K., Betran AP., Jahanfar S., Bohren MA, et al. Prevalence of and reasons for women's, family mem-bers', and health professionals' preferences for cesarean section in Iran: a mixed-methods systematic review. Reprod Health. 2021. 18:3.Spong CY., Berghella V., Wenstrom KD., Mercer BM., Saade GR. Pre-venting the first cesarean delivery: summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2012. 120:1181–93.Suwanrath C., Chunuan S., Matemanosak P., Pinjaroen S. Why do preg nant women prefer cesarean birth? A qualitative study in a tertiary care center in Southern Thailand. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021. 21:23.Tefera M., Assefa N., Mengistie B., Abrham A., Teji K., Worku T. Elective cesarean section on term pregnancies has a high risk for neonatal respiratory morbidity in developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. 2020. 8:286.Vimercati A., Greco P., Kardashi A., Rossi C., Loizzi V., Scioscia M, et al. Choice of cesarean section and perception of legal pressure. J Perinat Med. 2000. 28:111–7.Visco AG., Viswanathan M., Lohr KN., Wechter ME., Gartlehner G., Wu JM, et al. Cesarean delivery on maternal request: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 108:1517–29.Visser GHA., Ayres-de-Campos D., Barnea ER., de Bernis L., Di Renzo GC., Vidarte MFE, et al. FIGO position paper: how to stop the caesarean section epidemic. Lancet. 2018. 392:1286–7.World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet. 1985. 2:436–7.World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme. 10 April 2015. WHO Statement on caesarean section rates. Reprod Health Matters. 2015. 23:149–50.Zbiri S., Rozenberg P., Goffinet F., Milcent C. Cesarean delivery rate and staffing levels of the maternity unit. PLoS One. 2018. 13:e0207379.Zhang L., Zhang L., Li M., Xi J., Zhang X., Meng Z, et al. A cluster-randomized field trial to reduce cesarean section rates with a multifaceted intervention in Shanghai, China. BMC Med. 2020. 18:27.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Erratum: Narrative Review on the Trend of Childbirth in South Korea and Feasible Intervention to Reduce Cesarean Section Rate

- Vacuum extraction vaginal delivery: current trend and safety

- Expansion of Health Insurance Coverage for Prenatal Care and Its Association with Low Birth Weight and Premature Birth

- Chaning Trend of the Incidence on Cesarean Section

- A study for Pertinence in Emergent Cesarean Section