Cancer Res Treat.

2023 Jan;55(1):219-230. 10.4143/crt.2021.1166.

Establishing Patient-Derived Cancer Cell Cultures and Xenografts in Biliary Tract Cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Oncology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Center for Research and Development, Oncocross Ltd., Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Medical Science, Asan Medical Institute of Convergence Science and Technology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 4Center for Cancer Genome Discovery, Asan Institute for Life Science, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea

- 5University of Ulsan Digestive Diseases Research Center, Seoul, Korea

- 6Department of Pathology, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2538006

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2021.1166

Abstract

- Purpose

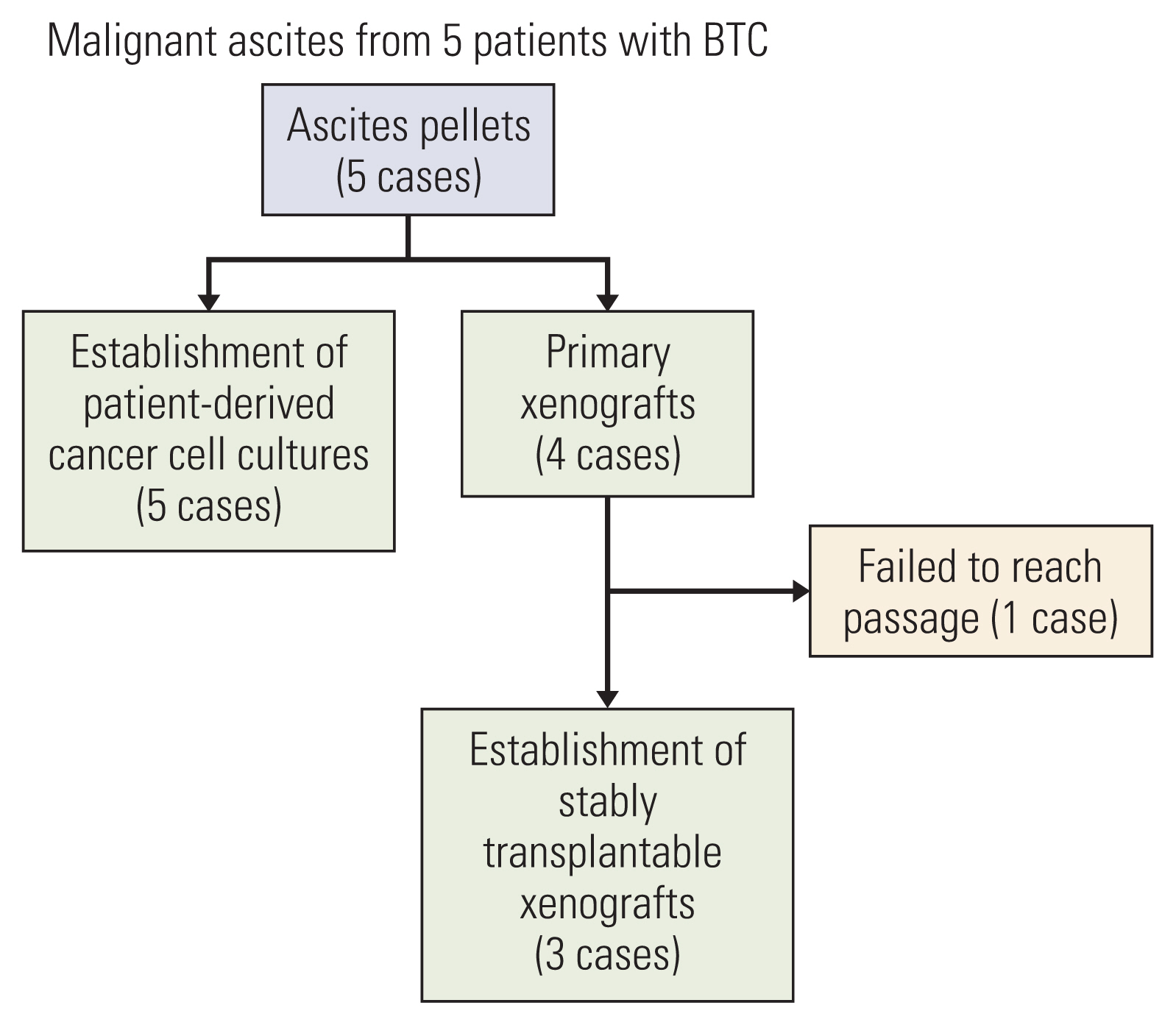

Biliary tract cancers (BTCs) are rare and show a dismal prognosis with limited treatment options. To improve our understanding of these heterogeneous tumors and develop effective therapeutic agents, suitable preclinical models reflecting diverse tumor characteristics are needed. We established and characterized new patient-derived cancer cell cultures and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models using malignant ascites from five patients with BTC.

Materials and Methods

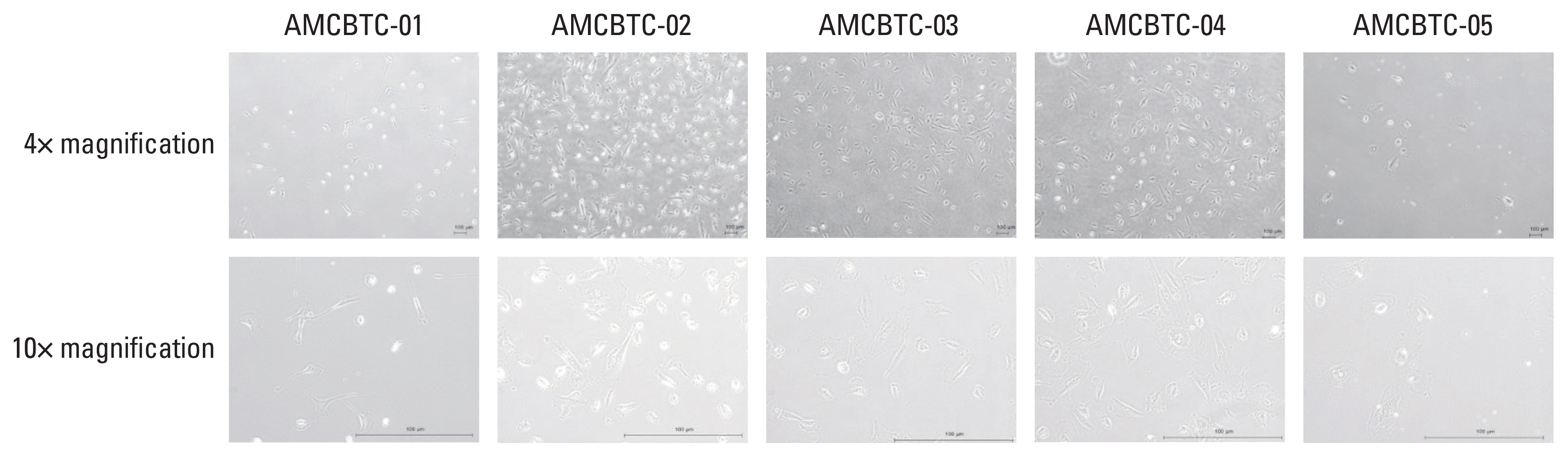

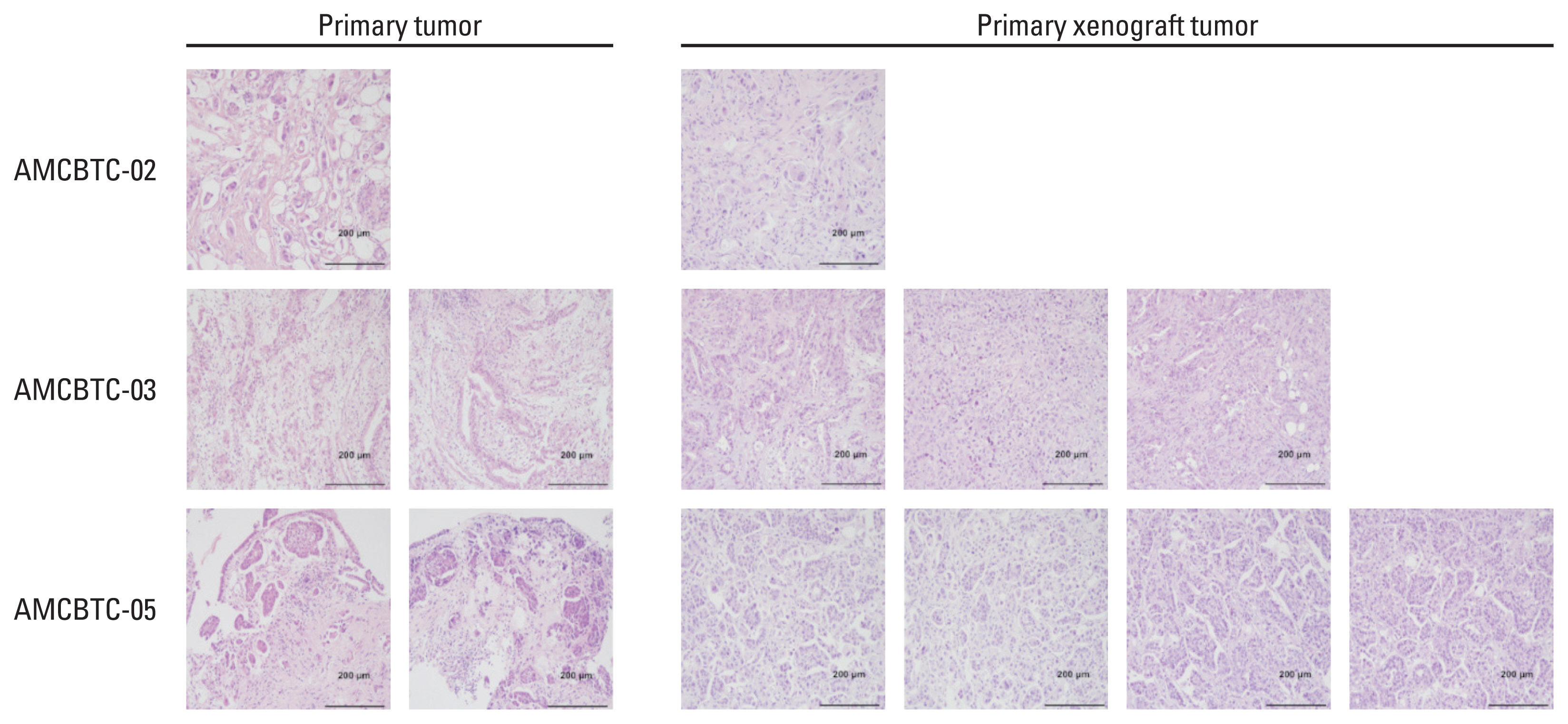

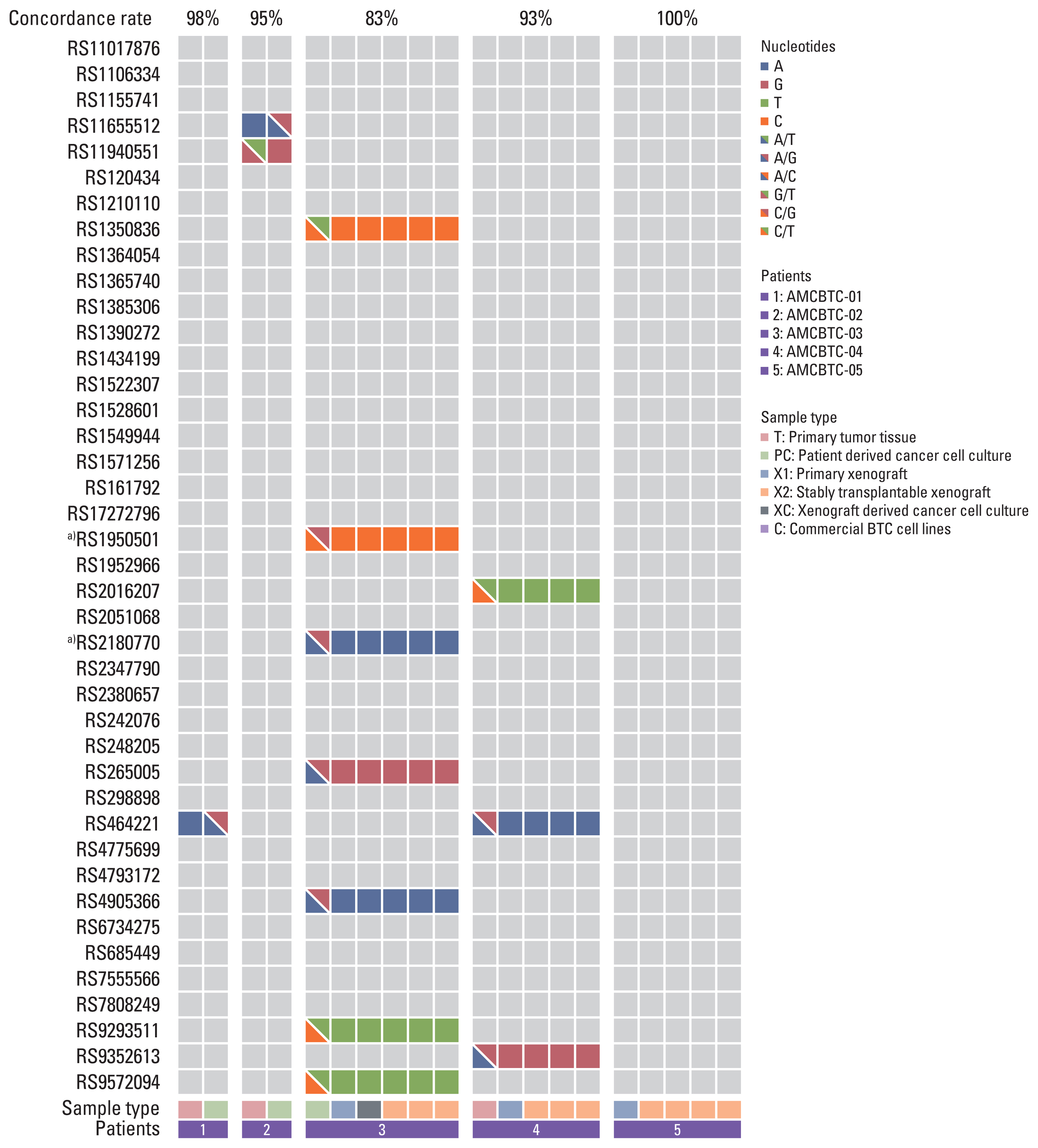

Five patient-derived cancer cell cultures and three PDX models derived from malignant ascites of five patients with BTC, AMCBTC-01, -02, -03, -04, and -05, were established. To characterize the models histogenetically and confirm whether characteristics of the primary tumor were maintained, targeted sequencing and histopathological comparison between primary tissue and xenograft tumors were performed.

Results

From malignant ascites of five BTC patients, five patient-derived cancer cell cultures (100% success rate), and three PDXs (60% success rate) were established. The morphological characteristics of three primary xenograft tumors were compared with those of matched primary tumors, and they displayed a similar morphology. The mutated genes in samples (models, primary tumor tissue, or both) from more than one patient were TP53 (n=2), KRAS (n=2), and STK11 (n=2). Overall, the pattern of commonly mutated genes in BTC cell cultures was different from that in commercially available BTC cell lines.

Conclusion

We successfully established the patient-derived cancer cell cultures and xenograft models derived from malignant ascites in BTC patients. These models accompanied by different genetic characteristics from commercially available models will help better understand BTC biology.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Kim BW, Oh CM, Choi HY, Park JW, Cho H, Ki M. Incidence and overall survival of biliary tract cancers in South Korea from 2006 to 2015: using the National Health Information Database. Gut Liver. 2019; 13:104–13.2. Jarnagin WR, Shoup M. Surgical management of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004; 24:189–99.3. Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, et al. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:1273–81.4. Ojima H, Yamagishi S, Shimada K, Shibata T. Establishment of various biliary tract carcinoma cell lines and xenograft models for appropriate preclinical studies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016; 22:9035–8.5. Fiebig HH, Maier A, Burger AM. Clonogenic assay with established human tumour xenografts: correlation of in vitro to in vivo activity as a basis for anticancer drug discovery. Eur J Cancer. 2004; 40:802–20.6. Cavalloni G, Peraldo-Neia C, Sassi F, Chiorino G, Sarotto I, Aglietta M, et al. Establishment of a patient-derived intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma xenograft model with KRAS mutation. BMC Cancer. 2016; 16:90.7. Maplanka C. Gallbladder cancer, treatment failure and relapses: the peritoneum in gallbladder cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2014; 45:245–55.8. Lee JY, Kim SY, Park C, Kim NK, Jang J, Park K, et al. Patient-derived cell models as preclinical tools for genome-directed targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2015; 6:25619–30.9. Golan T, Atias D, Barshack I, Avivi C, Goldstein RS, Berger R. Ascites-derived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma primary cell cultures as a platform for personalised medicine. Br J Cancer. 2014; 110:2269–76.10. Su X, Xue Y, Wei J, Huo X, Gong Y, Zhang H, et al. Establishment and characterization of gc-006-03, a novel human signet ring cell gastric cancer cell line derived from metastatic ascites. J Cancer. 2018; 9:3236–46.11. Jeon MJ, Chun SM, Kim D, Kwon H, Jang EK, Kim TY, et al. Genomic alterations of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma detected by targeted massive parallel sequencing in a BRAF(V600E) mutation-prevalent area. Thyroid. 2016; 26:683–90.12. Kim JE, Chun SM, Hong YS, Kim KP, Kim SY, Kim J, et al. Mutation burden and I index for detection of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer by targeted next-generation sequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2019; 21:241–50.13. Conway T, Wazny J, Bromage A, Tymms M, Sooraj D, Williams ED, et al. Xenome: a tool for classifying reads from xenograft samples. Bioinformatics. 2012; 28:i172–8.14. Kim M, Mun H, Sung CO, Cho EJ, Jeon HJ, Chun SM, et al. Patient-derived lung cancer organoids as in vitro cancer models for therapeutic screening. Nat Commun. 2019; 10:3991.15. Sakamoto Y, Yamagishi S, Okusaka T, Ojima H. Synergistic and pharmacotherapeutic effects of gemcitabine and cisplatin combined administration on biliary tract cancer cell lines. Cells. 2019; 8:1026.16. Watanabe M, Chigusa M, Takahashi H, Nakamura J, Tanaka H, Ohno T. High level of CA19-9, CA50, and CEA-producible human cholangiocarcinoma cell line changes in the secretion ratios in vitro or in vivo. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2000; 36:104–9.17. Miyagiwa M, Ichida T, Tokiwa T, Sato J, Sasaki H. A new human cholangiocellular carcinoma cell line (HuCC-T1) producing carbohydrate antigen 19/9 in serum-free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1989; 25:503–10.18. Lee PS, Fang J, Jessop L, Myers T, Raj P, Hu N, et al. RAD51B activity and cell cycle regulation in response to DNA damage in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2014; 8:135–44.19. Feng X, Song Q, Yu A, Tang H, Peng Z, Wang X. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 is a predictor of survival and plays a tumor suppressive role in colorectal cancer. Neoplasma. 2015; 62:592–601.20. Leiting JL, Murphy SJ, Bergquist JR, Hernandez MC, Ivanics T, Abdelrahman AM, et al. Biliary tract cancer patient-derived xenografts: surgeon impact on individualized medicine. JHEP Rep. 2020; 2:100068.21. Nakamura H, Arai Y, Totoki Y, Shirota T, Elzawahry A, Kato M, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet. 2015; 47:1003–10.22. Alexandrova EM, Mirza SA, Xu S, Schulz-Heddergott R, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. p53 loss-of-heterozygosity is a necessary prerequisite for mutant p53 stabilization and gain-of-function in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2017; 8:e2661.23. Lau DK, Mouradov D, Wasenang W, Luk IY, Scott CM, Williams DS, et al. Genomic profiling of biliary tract cancer cell lines reveals molecular subtypes and actionable drug targets. iScience. 2019; 21:624–37.24. Lamarca A, Barriuso J, McNamara MG, Valle JW. Molecular targeted therapies: ready for “prime time” in biliary tract cancer. J Hepatol. 2020; 73:170–85.25. Venkitaraman AR. Functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the biological response to DNA damage. J Cell Sci. 2001; 114:3591–8.26. Spizzo G, Puccini A, Xiu J, Goldberg RM, Grothey A, Shields AF, et al. Molecular profile of BRCA-mutated biliary tract cancers. ESMO Open. 2020; 5:e000682.27. Ku JL, Yoon KA, Kim IJ, Kim WH, Jang JY, Suh KS, et al. Establishment and characterisation of six human biliary tract cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2002; 87:187–93.28. Semenza GL. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment: a driving force for breast cancer progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016; 1863:382–91.29. Koh B, Jeon H, Kim D, Kang D, Kim KR. Effect of fibroblast co-culture on the proliferation, viability and drug response of colon cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2019; 17:2409–17.30. Okano M, Oshi M, Butash A, Okano I, Saito K, Kawaguchi T, et al. Orthotopic implantation achieves better engraftment and faster growth than subcutaneous implantation in breast cancer patient-derived xenografts. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2020; 25:27–36.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Microbiome and Biliary Tract Cancer

- Biology of SNU Cell Lines

- Current status of chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer

- Inflammation and Cancer Development in Pancreatic and Biliary Tract Cancer

- From past to pandemic: Health disparities in US hepatobiliary cancer mortality before and during COVID-19: Editorial on “Burden of mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma and biliary tract cancers by race and ethnicity and sex in US, 2018–2023”