Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.

2022 Dec;27(4):273-280. 10.6065/apem.2142226.113.

The association between C-reactive protein, metabolic syndrome, and prediabetes in Korean children and adolescents

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Korea Cancer Center Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2537239

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2142226.113

Abstract

- Purpose

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a state of chronic inflammation, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) indicates inflammation. This paper evaluates the associations between hsCRP and MetS and its components in Korean children and adolescents.

Methods

We analyzed the data of 1,247 subjects (633 males, 14.2±2.7 years) from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2016–2017. This study defined MetS and its components using the modified National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III) criteria.

Results

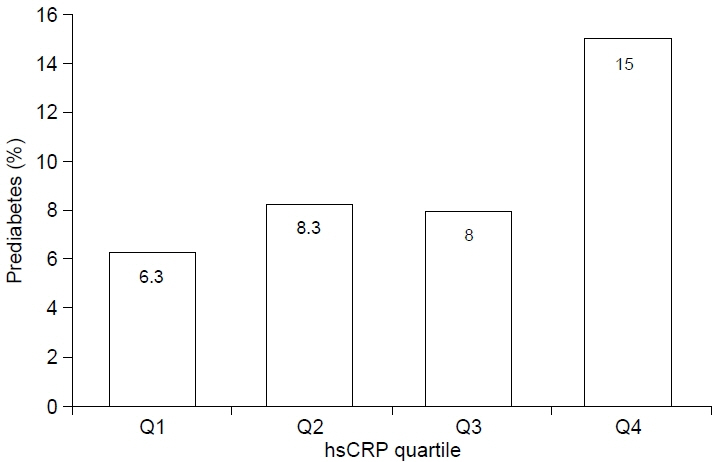

The mean hsCRP level was 0.86±1.57 mg/dL (median and interquartile range: 0.37 and 0.43 mg/dL). Subjects with MetS had higher hsCRP level than subjects without MetS (geometric mean: 1.08 mg/dL vs. 0.46 mg/dL, p<0.001). With a higher quartile value of hsCRP, the prevalence of MetS increased. Compared to the lowest quartile, the odds ratio (OR) for MetS in the highest quartile was 7.34 (3.07–17.55) after adjusting for age and sex. In the top quartile of hsCRP, the risk of abdominal obesity and low HDL was high after adjusting for age, sex, and other components of MetS. Additionally, the OR for prediabetes (HbA1c ≥5.7%) in the highest quartile was 2.70.

Conclusion

Serum hsCRP level was positively associated with MetS and prediabetes using NCEP-ATP III criteria. Among the MetS components, abdominal obesity and low HDL were highly correlated with hsCRP in Korean children and adolescents.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Glycated albumin may have a complementary role to glycated hemoglobin in glucose monitoring in childhood acute leukemia

Soo Yeun Sim, Su Jin Park, Jae Won Yoo, Seongkoo Kim, Jae Wook Lee, Nack-Gyun Chung, Bin Cho, Byung-Kyu Suh, Moon Bae Ahn

Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024;29(4):266-275. doi: 10.6065/apem.2346100.050.

Reference

-

References

1. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization;2008.2. Korea S. Annual report on the cause of death statistics 2010. Daejeon (Korea): Statistics Korea;2011. p. 48.3. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsén B, Lahti K, Nissén M, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24:683–9.4. Ford ES. The metabolic syndrome and mortality from cardiovascular disease and all-causes: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey II Mortality Study. Atherosclerosis. 2004; 173:309–14.5. Morrison JA, Friedman LA, Wang P, Glueck CJ. Metabolic syndrome in childhood predicts adult metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus 25 to 30 years later. J Pediatr. 2008; 152:201–6.6. Ma K, Jin X, Liang X, Zhao Q, Zhang X. Inflammatory mediators involved in the progression of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012; 28:388–94.7. Liu S, Tinker L, Song Y, Rifai N, Bonds DE, Cook NR, et al. A prospective study of inflammatory cytokines and diabetes mellitus in a multiethnic cohort of postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167:1676–85.8. Kanmani S, Kwon M, Shin MK, Kim MK. Association of C-reactive protein with risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, and role of obesity and hypertension: a large population-based Korean cohort study. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:4573.9. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Mokdad AH; National Health and Nutrition Examination. The metabolic syndrome and concentrations of C-reactive protein among U.S. youth. Diabetes Care. 2005; 28:878–81.10. Shin SH, Lee YJ, Lee YA, Kim JH, Lee SY, Shin CH. Highsensitivity c-reactive protein is associated with prediabetes and adiposity in Korean youth. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2020; 18:47–55.11. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, Kim Y, Kim K, Choi S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014; 43:69–77.12. Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, Nguyen M, Dietz WH. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003; 157:821–7.13. Moon JS, Lee SY, Nam CM, Choi JM, Choe BK, Seo JW, et al. 2007 Korean National Growth Charts: review of developmental process and an outlook. Korean Pediatr. 2008; 51:1–25.14. Kim SH, Park Y, Song YH, An HS, Shin JI, Oh JH, et al. Blood pressure reference values for normal weight Korean children and adolescents: data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1998-2016: The Korean Working Group of Pediatric Hypertension. Korean Circ J. 2019; 49:1167–80.15. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S62–9.16. Yi KH, Hwang JS, Kim EY, Lee SH, Kim DH, Lim JS. Prevalence of insulin resistance and cardiometabolic risk in Korean children and adolescents: a population-based study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014; 103:106–13.17. DeBoer MD. Obesity, systemic inflammation, and increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes among adolescents: a need for screening tools to target interventions. Nutrition. 2013; 29:379–86.18. Dallmeier D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Keaney JF Jr, Fontes JD, Meigs JB, et al. Metabolic syndrome and inflammatory biomarkers: a community-based cross-sectional study at the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2012; 4:28.19. Sethi JK, Hotamisligil GS. Metabolic Messengers: tumour necrosis factor. Nat Metab. 2021; 3:1302–12.20. Kim J, Pyo S, Yoon DW, Lee S, Lim JY, Heo JS, et al. The coexistence of elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein and homocysteine levels is associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome: a 6-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0206157.21. Oliveira AC, Oliveira AM, Adan LF, Oliveira NF, Silva AM, Ladeia AM. C-reactive protein and metabolic syndrome in youth: a strong relationship? Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16:1094–8.22. Ridker PM, Wilson PW, Grundy SM. Should C-reactive protein be added to metabolic syndrome and to assessment of global cardiovascular risk? Circulation. 2004; 109:2818–25.23. Cizmecioglu FM, Etiler N, Ergen A, Gormus U, Keser A, Hekim N, et al. Association of adiponectin, resistin and high sensitive CRP level with the metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009; 117:622–7.24. Soriano-Guillén L, Hernández-García B, Pita J, Domínguez-Garrido N, Del Río-Camacho G, Rovira A. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is a good marker of cardiovascular risk in obese children and adolescents. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008; 159:R1–4.25. Kitsios K, Papadopoulou M, Kosta K, Kadoglou N, Papagianni M, Tsiroukidou K. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels and metabolic disorders in obese and overweight children and adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013; 5:44–9.26. Suhett LG, Hermsdorff HHM, Rocha NP, Silva MA, Filgueiras MS, Milagres LC, et al. Increased C-reactive protein in brazilian children: association with cardiometabolic risk and metabolic syndrome components (PASE Study). Cardiol Res Pract. 2019; 2019:3904568.27. Kato K, Otsuka T, Saiki Y, Kobayashi N, Nakamura T, Kon Y, et al. Association between elevated C-reactive protein levels and prediabetes in adults, particularly impaired glucose tolerance. Can J Diabetes. 2019; 43:40–5. e2.28. de Las Heras Gala T, Herder C, Rutters F, Carstensen-Kirberg M, Huth C, Stehouwer CDA, et al. Association of changes in inflammation with variation in glycaemia, insulin resistance and secretion based on the KORA study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018; 34:e3063.29. Wang X, Bao W, Liu J, Ouyang YY, Wang D, Rong S, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2013; 36:166–75.30. Meyer C, Pimenta W, Woerle HJ, Van Haeften T, Szoke E, Mitrakou A, et al. Different mechanisms for impaired fasting glucose and impaired postprandial glucose tolerance in humans. Diabetes Care. 2006; 29:1909–14.31. Abdul-Ghani MA, Jenkinson CP, Richardson DK, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA. Insulin secretion and action in subjects with impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: results from the Veterans Administration Genetic Epidemiology Study. Diabetes. 2006; 55:1430–5.32. Cardellini M, Andreozzi F, Laratta E, Marini MA, Lauro R, Hribal ML, et al. Plasma interleukin-6 levels are increased in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance but not in those with impaired fasting glucose in a cohort of Italian Caucasians. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007; 23:141–5.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents

- Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents

- Therapeutic approaches to obesity and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents

- Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome among Children and Adolescents in Korea

- Clinical Predictive Factors for Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Children and Adolescents