Cardiovasc Prev Pharmacother.

2021 Oct;3(4):115-123. 10.36011/cpp.2021.3.e15.

Modeling of Changes in Creatine Kinase after HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor Prescription

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Medical Informatics, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

- 4Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Bucheon, Korea

- KMID: 2536938

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.36011/cpp.2021.3.e15

Abstract

- Background

Statin-associated muscle symptoms are one of the side effects that physicians should consider when prescribing statins. In this study, creatine kinase (CK) levels were measured following statin prescription, and various factors affecting the CK levels were determined using machine learning.

Methods

Changes in the CK were observed every 3 months for a 12-month period in patients who received statins for the first time at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital. For each visit, we developed four basic models based on changes in the CK levels. Extreme gradient boosting, a scalable end-to-end tree boosting algorithm, which employs a decision-tree-based ensemble machine learning algorithm, was used for the prediction of changes in the CK.

Results

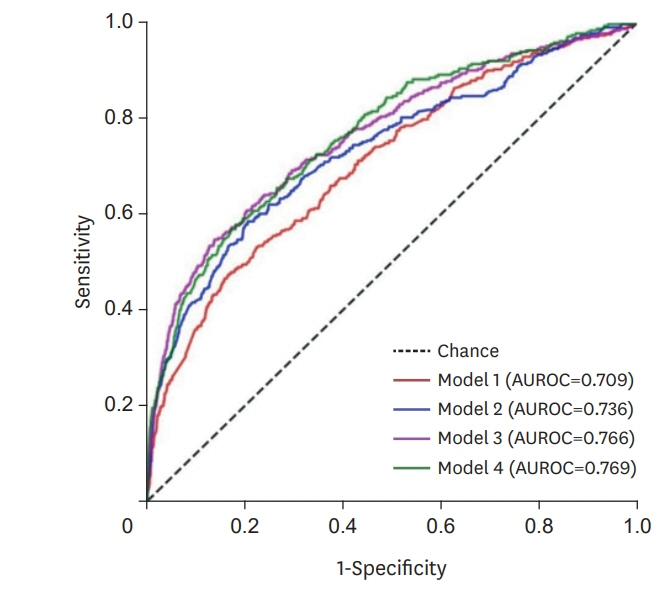

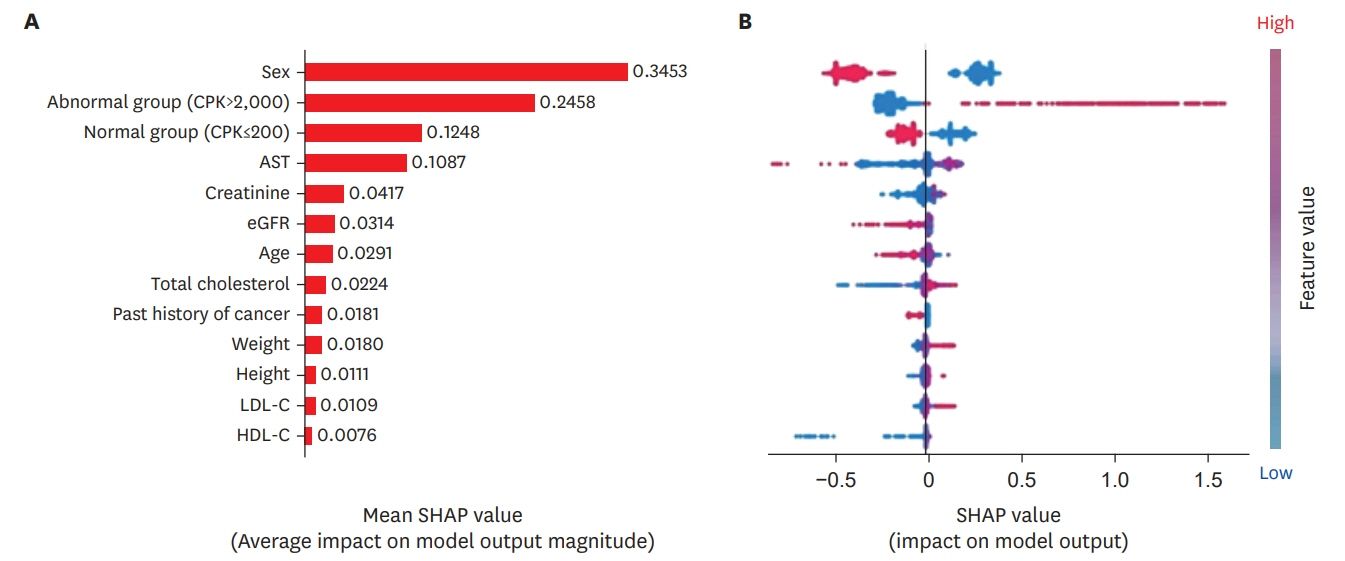

A total of 23,860 patients were included. Among them, 19 patients (0.08%) had increased CK levels of 2,000 IU·L−1 or more 3 months after statin prescription, and 65 patients (0.27%) exhibited CK levels of over 2,000 IU·L−1 at least once during the 12-month study period. The area under the receiver operator characteristic of each model for each visit was 0.709–0.769, and the accuracy was 0.700–0.803. In each of the models, the variables that had the strongest influence on changes in the CK were sex and previous CK value.

Conclusions

Through machine learning, factors influencing changes in the CK were identified. These results will provide the basis for future research, through which the optimal parameters of the CK prediction model can be found and the model can be used in clinical applications.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Davignon J. Beneficial cardiovascular pleiotropic effects of statins. Circulation. 2004; 109:III39–43.

Article2. Mihos CG, Pineda AM, Santana O. Cardiovascular effects of statins, beyond lipid-lowering properties. Pharmacol Res. 2014; 88:12–9.

Article3. Sewright KA, Clarkson PM, Thompson PD. Statin myopathy: incidence, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007; 9:389–96.

Article4. Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA. 2003; 289:1681–90.

Article5. Kim H, Kim N, Lee DH, Kim HS. Analysis of national pharmacovigilance data associated with statin use in Korea. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017; 121:409–13.

Article6. Tobert JA, Newman CB. The nocebo effect in the context of statin intolerance. J Clin Lipidol. 2016; 10:739–47.

Article7. Sathasivam S, Lecky B. Statin induced myopathy. BMJ. 2008; 337:a2286.

Article8. Mohaupt MG, Karas RH, Babiychuk EB, Sanchez-Freire V, Monastyrskaya K, Iyer L, Hoppeler H, Breil F, Draeger A. Association between statin-associated myopathy and skeletal muscle damage. CMAJ. 2009; 181:E11–8.

Article9. Hansen KE, Hildebrand JP, Ferguson EE, Stein JH. Outcomes in 45 patients with statin-associated myopathy. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:2671–6.

Article10. Tianqi C, Guestrin C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In : In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 2016; 2016 Aug 13-17; San Francisco, CA. New York, NY. Association for Computing Machinery. 2016. p. 785–94.11. Friedman JH. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann Stat. 2001; 29:1189–232.

Article12. Shavitt I, Segal E. Regularization learning networks: deep learning for tabular datasets. In : In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2018; 2018 Dec 3-8; Montréal, Canada. Red Hook, NY. Curran Associates Inc.2018. p. 1386–96.13. Abou Omar KB. XGBoost and LGBM for Porto Seguro's Kaggle challenge: A comparison Semester Project [Internet]. Zürich: ETH Zurich;2018. Jan [cited 2021 Sep 10]. Available from: https://pub.tik.ee.ethz.ch/students/2017-HS/SA-2017-98.pdf.14. Cai H, Zhong R, Wang C, Zhou R, Zhou K, Lee H, Xu K, Gao Z, Zhong R, Luo J, Zhou Y, Ding M, Li L, Li Q, Li D, Jiang N, Cheng X, Cui S, Ye H, Shen J. KDD CUP 2017 travel time prediction. [place unknown]: KDD;2017. [cited 2021 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.kdd.org/kdd2017/files/Task1_3rdPlace.pdf.15. Faasse K, Gamble G, Cundy T, Petrie KJ. Impact of television coverage on the number and type of symptoms reported during a health scare: a retrospective pre-post observational study. BMJ Open. 2012; 2:e001607.

Article16. Newman CB, Palmer G, Silbershatz H, Szarek M. Safety of atorvastatin derived from analysis of 44 completed trials in 9,416 patients. Am J Cardiol. 2003; 92:670–6.

Article17. Gupta A, Thompson D, Whitehouse A, Collier T, Dahlof B, Poulter N, Collins R, Sever P; ASCOT Investigators. Adverse events associated with unblinded, but not with blinded, statin therapy in the AngloScandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial and its non-randomised non-blind extension phase. Lancet. 2017; 389:2473–81.

Article18. Kim HS, Kim JH. Proceed with caution when using real world data and real world evidence. J Korean Med Sci. 2019; 34:e28.

Article19. Kim HS, Lee S, Kim JH. Real-world evidence versus randomized controlled trial: clinical research based on electronic medical records. J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33:e213.

Article20. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Derfoul A, Pak K, Miller FW, Milisenda JC, Grau-Junyent JM, Selva-O’Callaghan A, Carrion-Ribas C, Paik JJ, Albayda J, Christopher-Stine L, Lloyd TE, Corse AM, Mammen AL. Machine learning algorithms reveal unique gene expression profiles in muscle biopsies from patients with different types of myositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020; 79:1234–42.

Article21. Ooi BNS, Ying AF, Koh YZ, Jin Y, Yee SW, Lee JH, Chong SS, Tan JW, Liu J, Lee CG, Drum CL. Robust performance of potentially functional SNPs in machine learning models for the prediction of atorvastatin-induced myalgia. Front Pharmacol. 2021; 12:605764.

Article22. Chi CL, Wang J, Clancy TR, Robinson JG, Tonellato PJ, Adam TJ. Big data cohort extraction to facilitate machine learning to improve statin treatment. West J Nurs Res. 2017; 39:42–62.

Article23. Ogami C, Tsuji Y, Seki H, Kawano H, To H, Matsumoto Y, Hosono H. An artificial neural networkpharmacokinetic model and its interpretation using Shapley additive explanations. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2021; 10:760–8.

Article24. Merrick L, Taly A. The explanation game: explaining machine learning models using Shapley values. In : Holzinger A, Kieseberg P, Tjoa A, Weippl E, editors. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. CDMAKE 2020. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol 12279. Cham: Springer;2020. p. 17–38.25. Lempp D. An evidence-based guideline for treating dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients. J Nurse Pract. 2021; 17:910–5.

Article26. Harris LJ, Thapa R, Brown M, Pabbathi S, Childress RD, Heimberg M, Braden R, Elam MB. Clinical and laboratory phenotype of patients experiencing statin intolerance attributable to myalgia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011; 5:299–307.

Article27. Tokinaga K, Oeda T, Suzuki Y, Matsushima Y. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) might cause high elevations of creatine phosphokinase (CK) in patients with unnoticed hypothyroidism. Endocr J. 2006; 53:401–5.

Article28. van Puijenbroek EP, Du Buf-Vereijken PW, Spooren PF, van Doormaal JJ. Possible increased risk of rhabdomyolysis during concomitant use of simvastatin and gemfibrozil. J Intern Med. 1996; 240:403–4.

Article29. Maningat P, Gordon BR, Breslow JL. How do we improve patient compliance and adherence to long-term statin therapy? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013; 15:291.

Article30. Kim HS, Kim DJ, Yoon KH. Medical big data is not yet available: why we need realism rather than exaggeration. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2019; 34:349–54.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Myotonic Potentials in the Myopathy Induced by HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor

- A Case of Acquired Ichthyosis Developed During Cholesterol-lowering Treatment

- The Effects of Long Term Use of HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor on the Level of Lp (a)

- Effect of Coenzyme Q10 Supplementation in Statin-Treated Obese Rats

- Efficacy and safety of the combination therapy of HMG CoA reductase inhibitor and fibrate in combined dyslipidemia