Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol.

2022 Aug;15(3):205-212. 10.21053/ceo.2022.00815.

Tinnitus and the Triple Network Model: A Perspective

- Affiliations

-

- 1Section of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgical Sciences, Dunedin School of Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

- 2Global Brain Health Institute, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 3Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 4School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 5Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 6Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 7Sensory Organ Research Institute, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2532984

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2022.00815

Abstract

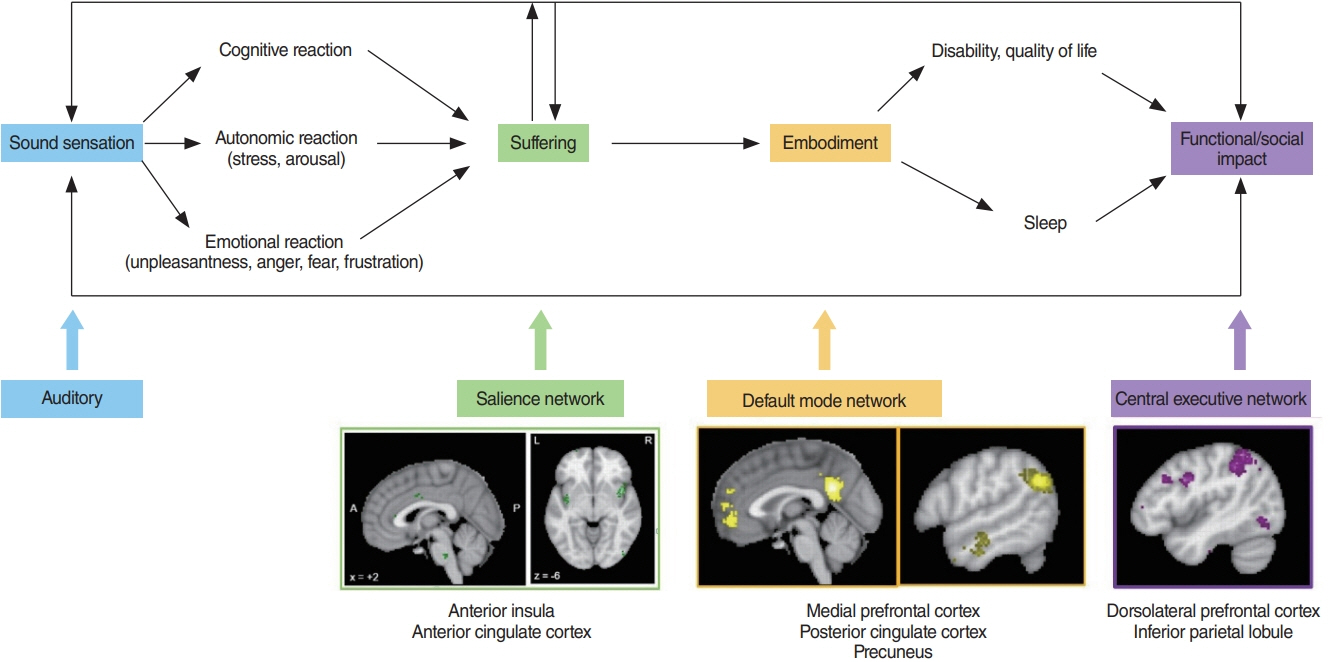

- Tinnitus is defined as the conscious awareness of a sound without an identifiable external sound source, and tinnitus disorder as tinnitus with associated suffering. Chronic tinnitus has been anatomically and phenomenologically separated into three pathways: a lateral “sound” pathway, a medial “suffering” pathway, and a descending noise-canceling pathway. Here, the triple network model is proposed as a unifying framework common to neuropsychiatric disorders. It proposes that abnormal interactions among three cardinal networks—the self-representational default mode network, the behavioral relevance-encoding salience network and the goal-oriented central executive network—underlie brain disorders. Tinnitus commonly leads to negative cognitive, emotional, and autonomic responses, phenomenologically expressed as tinnitus-related suffering, processed by the medial pathway. This anatomically overlaps with the salience network, encoding the behavioral relevance of the sound stimulus. Chronic tinnitus can also become associated with the self-representing default mode network and becomes an intrinsic part of the self-percept. This is likely an energy-saving evolutionary adaptation, by detaching tinnitus from sympathetic energy-consuming activity. Eventually, this can lead to functional disability by interfering with the central executive network. In conclusion, these three pathways can be extended to a triple network model explaining all tinnitus-associated comorbidities. This model paves the way for the development of individualized treatment modalities.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Tinnitus: Outpatient-Based Treatment

Jong-Geun Lee, Yongmin Cho, Hyunseok Choi, Gi Hwan Ryu, Jaeman Park, Dongha Kim, Sung-Won Chae, Jae-Jun Song

Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2024;67(5):270-276. doi: 10.3342/kjorl-hns.2023.00682.

Reference

-

1. De Ridder D, Schlee W, Vanneste S, Londero A, Weisz N, Kleinjung T, et al. Tinnitus and tinnitus disorder: theoretical and operational definitions (an international multidisciplinary proposal). Prog Brain Res. 2021; 260:1–25.2. Vanneste S, van de Heyning P, De Ridder D. The neural network of phantom sound changes over time: a comparison between recentonset and chronic tinnitus patients. Eur J Neurosci. 2011; Sep. 34(5):718–31.3. Wallhausser-Franke E, D’Amelio R, Glauner A, Delb W, Servais JJ, Hormann K, et al. Transition from acute to chronic tinnitus: predictors for the development of chronic distressing tinnitus. Front Neurol. 2017; Nov. 8:605.4. McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Somerset S, Hall D. A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hear Res. 2016; Jul. 337:70–9.5. Gibrin PC, Melo JJ, Marchiori LL. Prevalence of tinnitus complaints and probable association with hearing loss, diabetes mellitus and hypertension in elderly. Codas. 2013; 25(2):176–80.6. Baguley DM, Hoare DJ. Hyperacusis: major research questions. HNO. 2018; May. 66(5):358–63.7. Park E, Kim H, Choi IH, Han HM, Han K, Jung HH, et al. Psychiatric distress as a common risk factor for tinnitus and joint pain: a national population-based survey. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2020; Aug. 13(3):234–40.8. Cronlein T, Langguth B, Pregler M, Kreuzer PM, Wetter TC, Schecklmann M. Insomnia in patients with chronic tinnitus: cognitive and emotional distress as moderator variables. J Psychosom Res. 2016; Apr. 83:65–8.9. Asnis GM, Henderson M, Sylvester C, Thomas M, Kiran M, Richard De La G. Insomnia in tinnitus patients: a prospective study finding a significant relationship. Int Tinnitus J. 2021; Jan. 24(2):65–9.10. Clarke NA, Henshaw H, Akeroyd MA, Adams B, Hoare DJ. Associations between subjective tinnitus and cognitive performance: systematic review and meta-analyses. Trends Hear. 2020; Jan-Dec. 24:2331216520918416.11. Neff P, Simoes J, Psatha S, Nyamaa A, Boecking B, Rausch L, et al. The impact of tinnitus distress on cognition. Sci Rep. 2021; Jan. 11(1):2243.12. Dawes P, Newall J, Stockdale D, Baguley DM. Natural history of tinnitus in adults: a cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. BMJ Open. 2020; Dec. 10(12):e041290.13. Fuller T, Cima R, Langguth B, Mazurek B, Vlaeyen JW, Hoare DJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020; Jan. 1. (1):CD012614.14. De Ridder D, Elgoyhen AB, Romo R, Langguth B. Phantom percepts: tinnitus and pain as persisting aversive memory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; May. 108(20):8075–80.15. De Ridder D, Van de Heyning P. The Darwinian plasticity hypothesis for tinnitus and pain. Prog Brain Res. 2007; 166:55–60.16. De Ridder D, Vanneste S. The Bayesian brain in imbalance: medial, lateral and descending pathways in tinnitus and pain: a perspective. Prog Brain Res. 2021; 262:309–34.17. Jeanmonod D, Magnin M, Morel A. Low-threshold calcium spike bursts in the human thalamus: common physiopathology for sensory, motor and limbic positive symptoms. Brain. 1996; Apr. 119(Pt 2):363–75.18. Llinas RR, Ribary U, Jeanmonod D, Kronberg E, Mitra PP. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia: a neurological and neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by magnetoencephalography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999; Dec. 96(26):15222–7.19. Moller AR. Similarities between severe tinnitus and chronic pain. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000; Mar. 11(3):115–24.20. Moller AR. Similarities between chronic pain and tinnitus. Am J Otol. 1997; Sep. 18(5):577–85.21. Moller AR. Tinnitus and pain. Prog Brain Res. 2007; 166:47–53.22. Rauschecker JP, May ES, Maudoux A, Ploner M. Frontostriatal gating of tinnitus and chronic pain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015; Oct. 19(10):567–78.23. Tonndorf J. The analogy between tinnitus and pain: a suggestion for a physiological basis of chronic tinnitus. Hear Res. 1987; 28(2-3):271–5.24. Vanneste S, Song JJ, De Ridder D. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia detected by machine learning. Nat Commun. 2018; Mar. 9(1):1103.25. Vanneste S, To WT, De Ridder D. Tinnitus and neuropathic pain share a common neural substrate in the form of specific brain connectivity and microstate profiles. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019; Jan. 88:388–400.26. De Ridder D, De Mulder G, Menovsky T, Sunaert S, Kovacs S. Electrical stimulation of auditory and somatosensory cortices for treatment of tinnitus and pain. Prog Brain Res. 2007; 166:377–88.27. De Ridder D, Moller AR. Similarities between treatments of tinnitus and central pain. In : Moller AR, Langguth B, De Ridder D, Kleinjung T, editors. Textbook of tinnitus. New York (NY): Springer;2011. p. 753–62.28. Al-Chalabi M, Reddy V, Gupta S. Neuroanatomy, spinothalamic tract [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing;2022 [cited 2022 Jul 1]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29939601/.29. De Ridder D, Adhia D, Vanneste S. The anatomy of pain and suffering in the brain and its clinical implications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021; Nov. 130:125–46.30. De Ridder D, Vanneste S. Burst and tonic spinal cord stimulation: different and common brain mechanisms. Neuromodulation. 2016; Jan. 19(1):47–59.31. Frot M, Mauguiere F, Magnin M, Garcia-Larrea L. Parallel processing of nociceptive A-delta inputs in SII and midcingulate cortex in humans. J Neurosci. 2008; Jan. 28(4):944–52.32. Vanneste S, De Ridder D. Chronic pain as a brain imbalance between pain input and pain suppression. Brain Commun. 2021. Feb. 3. (1):fcab014.33. Yearwood T, De Ridder D, Yoo HB, Falowski S, Venkatesan L, Ting To W, et al. Comparison of neural activity in chronic pain patients during tonic and burst spinal cord stimulation using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Neuromodulation. 2020; Jan. 23(1):56–63.34. Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013; Jul. 14(7):502–11.35. Rainville P, Carrier B, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell CM, Duncan GH. Dissociation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain using hypnotic modulation. Pain. 1999; Aug. 82(2):159–71.36. Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011; Oct. 15(10):483–506.37. Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003; Jan. 100(1):253–8.38. Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008; Mar. 1124:1–38.39. Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007; Feb. 27(9):2349–56.40. Vincent JL, Kahn I, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Buckner RL. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2008; Dec. 100(6):3328–42.41. Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; Jul. 102(27):9673–8.42. Goulden N, Khusnulina A, Davis NJ, Bracewell RM, Bokde AL, McNulty JP, et al. The salience network is responsible for switching between the default mode network and the central executive network: replication from DCM. Neuroimage. 2014; Oct. 99:180–90.43. Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010; Jun. 214(5-6):655–67.44. Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; Aug. 105(34):12569–74.45. Sha Z, Wager TD, Mechelli A, He Y. Common dysfunction of large-scale neurocognitive networks across psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2019; Mar. 85(5):379–88.46. Sha Z, Xia M, Lin Q, Cao M, Tang Y, Xu K, et al. Meta-connectomic analysis reveals commonly disrupted functional architectures in network modules and connectors across brain disorders. Cereb Cortex. 2018; Dec. 28(12):4179–94.47. De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Smith M, Adhia D. Pain and the triple network model. Front Neurol. 2022; Mar. 13:757241.48. Boly M, Faymonville ME, Peigneux P, Lambermont B, Damas F, Luxen A, et al. Cerebral processing of auditory and noxious stimuli in severely brain injured patients: differences between VS and MCS. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2005; Jul-Sep. 15(3-4):283–9.49. Boly M, Faymonville ME, Peigneux P, Lambermont B, Damas P, Del Fiore G, et al. Auditory processing in severely brain injured patients: differences between the minimally conscious state and the persistent vegetative state. Arch Neurol. 2004; Feb. 61(2):233–8.50. Boly M, Garrido MI, Gosseries O, Bruno MA, Boveroux P, Schnakers C, et al. Preserved feedforward but impaired top-down processes in the vegetative state. Science. 2011; May. 332(6031):858–62.51. Laureys S, Faymonville ME, Degueldre C, Fiore GD, Damas P, Lambermont B, et al. Auditory processing in the vegetative state. Brain. 2000; Aug. 123(Pt 8):1589–601.52. Laureys S, Perrin F, Faymonville ME, Schnakers C, Boly M, Bartsch V, et al. Cerebral processing in the minimally conscious state. Neurology. 2004; Sep. 63(5):916–8.53. De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Weisz N, Londero A, Schlee W, Elgoyhen AB, et al. An integrative model of auditory phantom perception: tinnitus as a unified percept of interacting separable subnetworks. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014; Jul. 44:16–32.54. De Ridder D, Joos K, Vanneste S. Anterior cingulate implants for tinnitus: report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg. 2016; Apr. 124(4):893–901.55. Vanneste S, Plazier M, der Loo Ev, de Heyning PV, Congedo M, De Ridder D. The neural correlates of tinnitus-related distress. Neuroimage. 2010; Aug. 52(2):470–80.56. De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Congedo M. The distressed brain: a group blind source separation analysis on tinnitus. PLoS One. 2011; 6(10):e24273.57. Beard AW. Results of leucotomy operations for tinnitus. J Psychosom Res. 1965; Sep. 9(1):29–32.58. Elithorn A. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of tinnitus. Proc R Soc Med. 1953; Oct. 46(10):832–3.59. van der Loo E, Gais S, Congedo M, Vanneste S, Plazier M, Menovsky T, et al. Tinnitus intensity dependent gamma oscillations of the contralateral auditory cortex. PLoS One. 2009; Oct. 4(10):e7396.60. Smits M, Kovacs S, de Ridder D, Peeters RR, van Hecke P, Sunaert S. Lateralization of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) activation in the auditory pathway of patients with lateralized tinnitus. Neuroradiology. 2007; Aug. 49(8):669–79.61. Song JJ, Vanneste S, De Ridder D. Dysfunctional noise cancelling of the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in tinnitus patients. PLoS One. 2015; Apr. 10(4):e0123538.62. Seydell-Greenwald A, Leaver AM, Turesky TK, Morgan S, Kim HJ, Rauschecker JP. Functional MRI evidence for a role of ventral prefrontal cortex in tinnitus. Brain Res. 2012; Nov. 1485:22–39.63. Axelsson A, Ringdahl A. Tinnitus: a study of its prevalence and characteristics. Br J Audiol. 1989; Feb. 23(1):53–62.64. Cima RF, Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW. Catastrophizing and fear of tinnitus predict quality of life in patients with chronic tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2011; Sep-Oct. 32(5):634–41.65. Weise C, Hesser H, Andersson G, Nyenhuis N, Zastrutzki S, Kroner-Herwig B, et al. The role of catastrophizing in recent onset tinnitus: its nature and association with tinnitus distress and medical utilization. Int J Audiol. 2013; Mar. 52(3):177–88.66. Hebert S, Lupien SJ. The sound of stress: blunted cortisol reactivity to psychosocial stress in tinnitus sufferers. Neurosci Lett. 2007; Jan. 411(2):138–42.67. Hebert S, Lupien SJ. Salivary cortisol levels, subjective stress, and tinnitus intensity in tinnitus sufferers during noise exposure in the laboratory. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009; Jan. 212(1):37–44.68. Hinton DE, Chhean D, Pich V, Hofmann SG, Barlow DH. Tinnitus among Cambodian refugees: relationship to PTSD severity. J Trauma Stress. 2006; Aug. 19(4):541–6.69. Kogler L, Muller VI, Chang A, Eickhoff SB, Fox PT, Gur RC, et al. Psychosocial versus physiological stress: meta-analyses on deactivations and activations of the neural correlates of stress reactions. Neuroimage. 2015; Oct. 119:235–51.70. Koolhaas JM, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B, de Boer SF, Flugge G, Korte SM, et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011; Apr. 35(5):1291–301.71. Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009; Jun. 10(6):397–409.72. Russell G, Lightman S. The human stress response. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019; Sep. 15(9):525–34.73. Staufenbiel SM, Penninx BW, Spijker AT, Elzinga BM, van Rossum EF. Hair cortisol, stress exposure, and mental health in humans: a systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013; Aug. 38(8):1220–35.74. Gilam G, Lin T, Fruchter E, Hendler T. Neural indicators of interpersonal anger as cause and consequence of combat training stress symptoms. Psychol Med. 2017; Jul. 47(9):1561–72.75. Joos K, Vanneste S, De Ridder D. Disentangling depression and distress networks in the tinnitus brain. PLoS One. 2012; 7(7):e40544.76. Vachon-Presseau E, Martel MO, Roy M, Caron E, Albouy G, Marin MF, et al. Acute stress contributes to individual differences in pain and pain-related brain activity in healthy and chronic pain patients. J Neurosci. 2013; Apr. 33(16):6826–33.77. Telesford QK, Simpson SL, Burdette JH, Hayasaka S, Laurienti PJ. The brain as a complex system: using network science as a tool for understanding the brain. Brain Connect. 2011; Oct. 1(4):295–308.78. Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009; Mar. 10(3):186–98.79. Sporns O, Chialvo DR, Kaiser M, Hilgetag CC. Organization, development and function of complex brain networks. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004; Sep. 8(9):418–25.80. Suarez LE, Markello RD, Betzel RF, Misic B. Linking structure and function in macroscale brain networks. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020; Apr. 24(4):302–15.81. Mohan A, De Ridder D, Vanneste S. Graph theoretical analysis of brain connectivity in phantom sound perception. Sci Rep. 2016; Feb. 6:19683.82. Elgoyhen AB, Langguth B, Vanneste S, De Ridder D. Tinnitus: network pathophysiology-network pharmacology. Front Syst Neurosci. 2012; Jan. 6:1.83. Schmidt SA, Akrofi K, Carpenter-Thompson JR, Husain FT. Default mode, dorsal attention and auditory resting state networks exhibit differential functional connectivity in tinnitus and hearing loss. PLoS One. 2013; Oct. 8(10):e76488.84. Song JJ, Park J, Koo JW, Lee SY, Vanneste S, De Ridder D, et al. The balance between Bayesian inference and default mode determines the generation of tinnitus from decreased auditory input: a volume entropy-based study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021; Aug. 42(12):4059–73.85. Eggermont JJ. Separate auditory pathways for the induction and maintenance of tinnitus and hyperacusis. Prog Brain Res. 2021; 260:101–27.86. Hu J, Cui J, Xu JJ, Yin X, Wu Y, Qi J. The neural mechanisms of tinnitus: a perspective from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Front Neurosci. 2021; Feb. 15:621145.87. Zhou GP, Shi XY, Wei HL, Qu LJ, Yu YS, Zhou QQ, et al. Disrupted intraregional brain activity and functional connectivity in unilateral acute tinnitus patients with hearing loss. Front Neurosci. 2019; Sep. 13:1010.88. Chen YC, Zhang H, Kong Y, Lv H, Cai Y, Chen H, et al. Alterations of the default mode network and cognitive impairment in patients with unilateral chronic tinnitus. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018; Nov. 8(10):1020–9.89. Schmidt SA, Carpenter-Thompson J, Husain FT. Connectivity of precuneus to the default mode and dorsal attention networks: a possible invariant marker of long-term tinnitus. Neuroimage Clin. 2017; Jul. 16:196–204.90. Lanting C, WozAniak A, van Dijk P, Langers DR. Tinnitus- and task-related differences in resting-state networks. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016; Apr. 894:175–87.91. Chen YC, Chen H, Bo F, Xu JJ, Deng Y, Lv H, et al. Tinnitus distress is associated with enhanced resting-state functional connectivity within the default mode network. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018; Aug. 14:1919–27.92. Lee SY, Choi BY, Koo JW, De Ridder D, Song JJ. Cortical oscillatory signatures reveal the prerequisites for tinnitus perception: a comparison of subjects with sudden sensorineural hearing loss with and without tinnitus. Front Neurosci. 2020; Nov. 14:596647.93. Han JJ, Ridder D, Vanneste S, Chen YC, Koo JW, Song JJ. Pre-treatment ongoing cortical oscillatory activity predicts improvement of tinnitus after partial peripheral reafferentation with hearing aids. Front Neurosci. 2020; May. 14:410.94. Friston K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010; Feb. 11(2):127–38.95. Friston K. The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009; Jul. 13(7):293–301.96. Hitze B, Hubold C, van Dyken R, Schlichting K, Lehnert H, Entringer S, et al. How the selfish brain organizes its supply and demand. Front Neuroenergetics. 2010; Jun. 2:7.97. Peters A, Schweiger U, Pellerin L, Hubold C, Oltmanns KM, Conrad M, et al. The selfish brain: competition for energy resources. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004; Apr. 28(2):143–80.98. Taylor KS, Kucyi A, Millar PJ, Murai H, Kimmerly DS, Morris BL, et al. Association between resting-state brain functional connectivity and muscle sympathetic burst incidence. J Neurophysiol. 2016; Feb. 115(2):662–73.99. Babo-Rebelo M, Richter CG, Tallon-Baudry C. Neural responses to heartbeats in the default network encode the self in spontaneous thoughts. J Neurosci. 2016; Jul. 36(30):7829–40.100. Sjostrom L, Schutz Y, Gudinchet F, Hegnell L, Pittet PG, Jequier E. Epinephrine sensitivity with respect to metabolic rate and other variables in women. Am J Physiol. 1983; Nov. 245(5 Pt 1):E431–42.101. Fellows IW, Bennett T, MacDonald IA. The effect of adrenaline upon cardiovascular and metabolic functions in man. Clin Sci (Lond). 1985; Aug. 69(2):215–22.102. Holland-Fischer P, Greisen J, Grofte T, Jensen TS, Hansen PO, Vilstrup H. Increased energy expenditure and glucose oxidation during acute nontraumatic skin pain in humans. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009; Apr. 26(4):311–7.103. Xu Z, Li Y, Wang J, Li J. Effect of postoperative analgesia on energy metabolism and role of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors for postoperative pain management after abdominal surgery in adults. Clin J Pain. 2013; Jul. 29(7):570–6.104. Straub RH. The brain and immune system prompt energy shortage in chronic inflammation and ageing. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017; Dec. 13(12):743–51.105. Whitehorn JC, Lundholm H, Gardner GE. The metabolic rate in emotional moods induced by suggestion in hypnosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1930; Jan. 86(4):661–6.106. Schmidt WD, O’Connor PJ, Cochrane JB, Cantwell M. Resting metabolic rate is influenced by anxiety in college men. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1996; Feb. 80(2):638–42.107. Mohamad N, Hoare DJ, Hall DA. The consequences of tinnitus and tinnitus severity on cognition: a review of the behavioural evidence. Hear Res. 2016; Feb. 332:199–209.108. Tegg-Quinn S, Bennett RJ, Eikelboom RH, Baguley DM. The impact of tinnitus upon cognition in adults: a systematic review. Int J Audiol. 2016; Oct. 55(10):533–40.109. Vanneste S, Faber M, Langguth B, De Ridder D. The neural correlates of cognitive dysfunction in phantom sounds. Brain Res. 2016; Jul. 1642:170–9.110. Maudoux A, Lefebvre P, Cabay JE, Demertzi A, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Laureys S, et al. Connectivity graph analysis of the auditory resting state network in tinnitus. Brain Res. 2012; Nov. 1485:10–21.111. Maudoux A, Lefebvre P, Cabay JE, Demertzi A, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Laureys S, et al. Auditory resting-state network connectivity in tinnitus: a functional MRI study. PLoS One. 2012; May. 7(5):e36222.112. Shahsavarani S, Schmidt SA, Khan RA, Tai Y, Husain FT. Salience, emotion, and attention: the neural networks underlying tinnitus distress revealed using music and rest. Brain Res. 2021; Mar. 1755:147277.113. Kandeepan S, Maudoux A, Ribeiro de Paula D, Zheng JY, Cabay JE, Gomez F, et al. Tinnitus distress: a paradoxical attention to the sound. J Neurol. 2019; Sep. 266(9):2197–207.114. Xu XM, Jiao Y, Tang TY, Lu CQ, Zhang J, Salvi R, et al. Altered spatial and temporal brain connectivity in the salience network of sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus. Front Neurosci. 2019; Mar. 13:246.115. Amaral AA, Langers DR. Tinnitus-related abnormalities in visual and salience networks during a one-back task with distractors. Hear Res. 2015; Aug. 326:15–29.116. De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Freeman W. The Bayesian brain: phantom percepts resolve sensory uncertainty. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014; Jul. 44:4–15.