Hanyang Med Rev.

2016 May;36(2):120-124. 10.7599/hmr.2016.36.2.120.

Tinnitus Retraining Therapy

- Affiliations

-

- 1Soree Ear Clinic, Seoul, Korea. earclinic@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2164670

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.7599/hmr.2016.36.2.120

Abstract

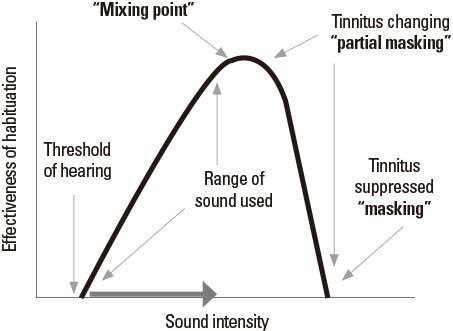

- According to the Jastreboff's neurophysiological model of tinnitus, if negative associations are attached to the tinnitus signal, tinnitus is perceived to be a threat or a danger and it activates the autonomic nervous and limbic systems. Consequently patient's awareness of tinnitus is heightened and so patient perceives it to be louder and more persistent. Jastreboff and Hazell started tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) based on the neurophysiological model of tinnitus. The purpose of TRT is blocking tinnitus from activating the sympathetic nervous and limbic systems (habituation of reaction) and from reaching the cerebral cortex (habituation of perception). TRT is composed of two components directive counseling that tries to reclassify tinnitus into the meaningless stimuli and sound therapy that decreases the relative strength of the tinnitus signal. Physicians try to put patient's tinnitus into the territory of meaningless stimuli through retraining the brain (habituation of reaction). Because the brain habituates all unimportant stimuli, if habituation of reaction is fully achieved, habituation of perception will follow automatically. In most clinical results, clinical success rates of TRT approach or exceed 80% improvement. Early improvement can be achieved during the first few months, followed by additional progressive improvement. It should be recommended that the patient continue treatment at least 18 months.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Tinnitus: Overview

Chul Won Park

Hanyang Med Rev. 2016;36(2):79-80. doi: 10.7599/hmr.2016.36.2.79.

Reference

-

1. Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res. 1990; 8:221–254.

Article2. Jastreboff PJ, Hazell JWP. A neurophysiological approach to tinnitus: clinical implications. Br J Audiol. 1993; 27:7–17.

Article3. Jastreboff PJ, Gray WC, Gold SL. Neurophysiological approach to tinnitus patients. Am J Otol. 1996; 17:236–240.4. Davis A, El Refaie A. Tinnitus Handbook. In : Tyler RS, editor. San Diego: Singular Thomson Learning;2000. p. 1–23.5. Jastreboff PJ, Hazell JWP, Graham RL. Neurophysiological model of tinnitus: dependence of the minimal masking level on treatment outcome. Hear Res. 1994; 80:216–232.

Article6. Henry JA, Jastreboff MM, Jastreboff PJ, schechter MA, Fausti SA. Assessment of patients for treatment with tinnitus retraining therapy. J Am Acad Audiol. 2002; 13:523–544.

Article7. Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Coad ML, Towsley ML, Wack DS, Murphy BW. The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus: evidence for limbic system links and neural plasticity. Neurology. 1998; 50:114–120.8. Lockwood AH, Salvi RJ, Burkard RF. Tinnitus. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:904–910.

Article9. Mirz F, Pedersen B, Ishizu K, Johannsen P, Ovesen T, Stødkilde-Jørgensen H, et al. Positron emission tomography of cortical centers of tinnitus. Hear Res. 1999; 134:133–144.

Article10. Mirz F, Gjedde A, Ishizu K, Pedersen CB. Cortical networks subserving the perception of tinnitus-a PET study. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000; 543:241–243.11. Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996; 122:143–148.

Article12. Newman CW, Sandridge SA, Jacobson GP. Psychometric adequacy of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998; 9:153–160.13. Adamchic I, Langguth B, Hauptmann C, Tass PA. Psychometric evaluation of visual analog scale for the assessment of chronic tinnitus. Am J Audiol. 2012; 21:215–225.

Article14. Lee HK, Kim CW, Chung MH, Kim HN. The effectiveness of the directive counseling in tinnitus retraining therapy. Korean J Otolaryngol. 2004; 47:217–221.15. Jastreboff PJ. 25 years of tinnitus retraining therapy. HNO. 2015; 63:307–311.

Article16. Lee HK. Tinnitus retraining therapy. Korean J Audiol. 2002; 6:71–75.17. Park SN, Yeo SW, Chung SH, Lee SJ, Park YS, Suh BD. Clinical implication and therapeutic efficacy of tinnitus retraining therapy. Korean J Otolaryngol. 2002; 45:231–237.18. Jastreboff PJ, Jastreboff MM. Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) as a method for treatment of tinnitus and hyperacusis patients. J Am Acad Audiol. 2000; 11:162–177.19. Jastreboff PJ, Jastreboff MM. Tinnitus retraining therapy for patients with tinnitus and decreased sound tolerance. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003; 36:321–336.

Article20. Cima RF, Maes IH, Joore MA, Scheyen DJ, El Refaie A, Baquley DM, et al. Specialised treatment based on cognitive behaviour therapy versus usual care for tinnitus: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012; 379:1951–1959.

Article21. Phillips JS, McFerran D. Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) for tinnitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 17(3):CD007330.

Article22. Henry JA, Schechter MA, Zaugg TL, Griest S, Jastreboff PJ, Vernon JA, et al. Outcomes of clinical trial: tinnitus masking versus tinnitus retraining therapy. J Am Acad Audidol. 2006; 17:104–132.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- The Effectiveness of the Directive Counseling in Tinnitus Retraining Therapy

- Clinical Implication and Therapeutic Efficacy of Tinnitus Retraining Therapy

- Psychological Analysis with Symptom Check List-90-Revision in Patients with Tinnitus

- Short Term Effect of Mixed Tinnitus Retraining Therapy

- Non-pharmacological therapy for tinnitus