Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.

2022 Jun;27(2):105-112. 10.6065/apem.2142146.073.

Pathological brain lesions in girls with central precocious puberty at initial diagnosis in Southern Vietnam

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh city, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- 2Department of Nephrology and Endocrinology, Children’s Hospital 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- 3Department of Peadiatric Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh city, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- 4Children’s Hospital 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- 5International Master/PhD Program in Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 6Professional Master Program in Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 7Research Center for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 8School of Nutrition and Health Sciences, Taipei Medical University, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 9Graduate Institute of Metabolism and Obesity Sciences, Taipei Medical University, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 10Nutrition Research Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei City, Taiwan

- KMID: 2531274

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.6065/apem.2142146.073

Abstract

- Purpose

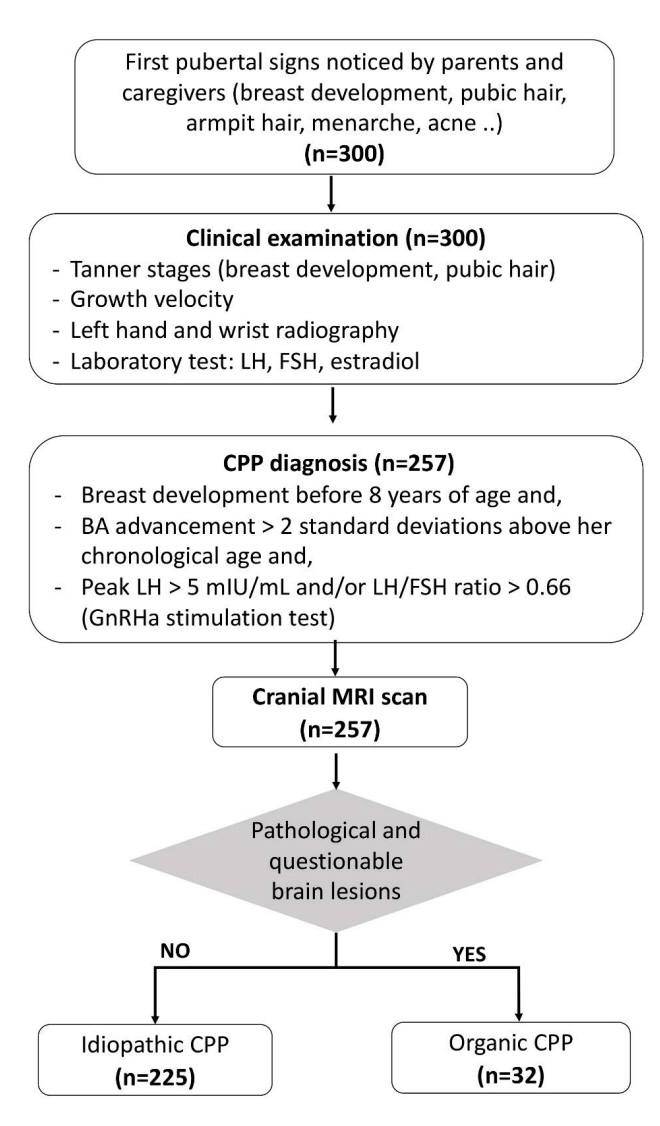

Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended to identify intracranial lesions in girls with central precocious puberty (CPP). Yet, the use of routine MRI scans in girls with CPP is still debatable, as pathological findings in girls 6 years of age or older with CPP are limited. Therefore, we aimed to identify the prevalence of brain lessons in CPP patients stratified by age group (0–2, 2–6, and 6–8 years).

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study recruited 257 girls diagnosed with CPP for 6 years (2010–2016). MRI was used to detect brain abnormalities. Levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and sex hormones in blood samples were measured.

Results

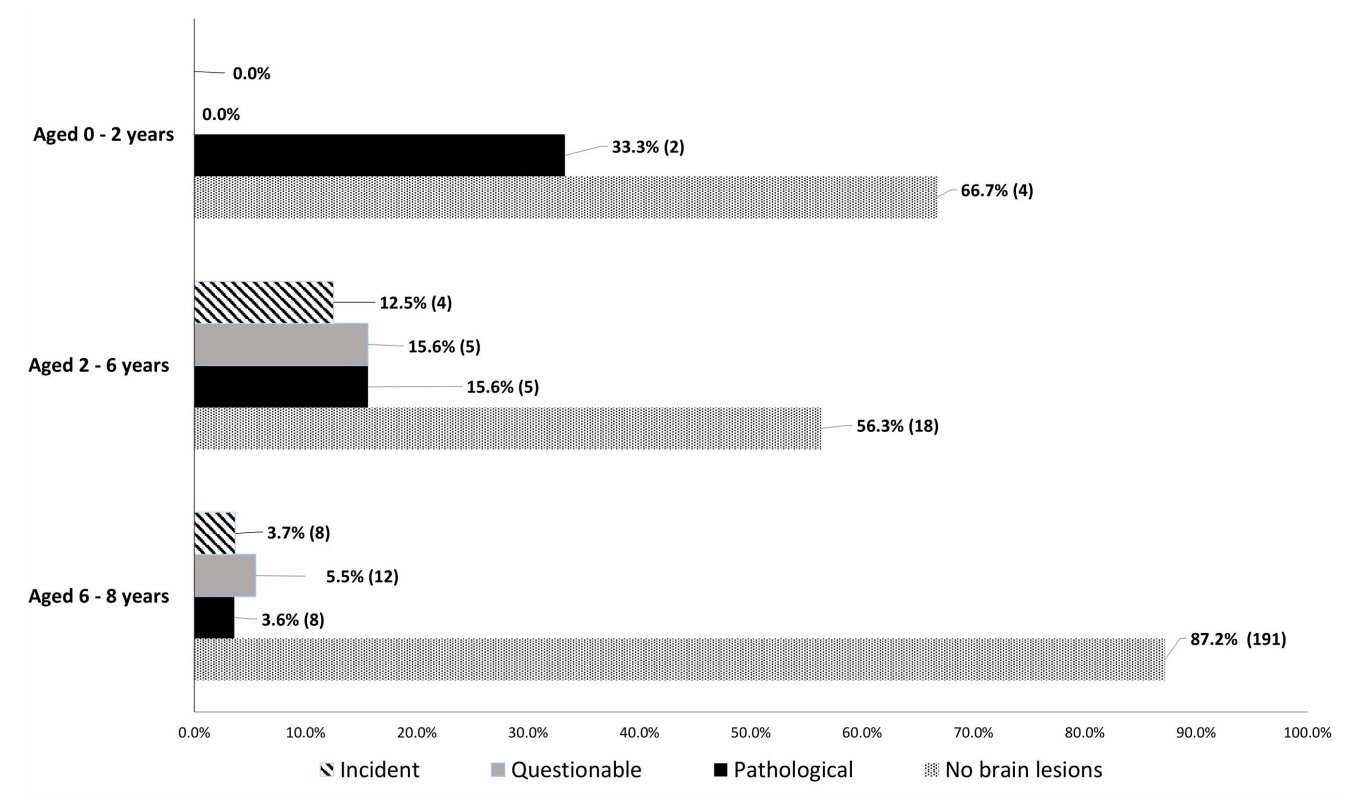

Most girls had no brain lesions (82.9%, n=213), and of the minor proportion of girls with CPP that exhibited brain lesions (17.1%, n=44), 32 girls had organic CPP. Pathological findings were detected in 33.3% (2 of 6) of girls aged 0–2 years, 15.6% (5 of 32) of girls aged 2–6 years, and 3.6% (8 of 219) of girls aged 6–8 years. Hypothalamic hamartoma and tumors in the pituitary stalk were the most common pathological findings. The likelihood of brain lesions decreased with age. Girls with organic CPP were more likely to be younger (6.1±2.4 vs. 7.3±1.3 years, p<0.01) than girls with idiopathic CPP.

Conclusion

Older girls appeared to have a lower prevalence of organic CPP. Clinicians should cautiously use cranial MRI for girls aged 6–8 years with CPP.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Kaplowitz PB, Oberfield SE. Reexamination of the age limit for defining when puberty is precocious in girls in the United States: implications for evaluation and treatment. Pediatrics. 1999; 104:936–41.2. Jung H, Ojeda SR. Pathogenesis of precocious puberty in hypothalamic hamartoma. Horm Res. 2002; 57 Suppl 2:31–4.3. Latronico AC, Brito VN, Carel JC. Causes, diagnosis, and treatment of central precocious puberty. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016; 4:265–74.4. Dossus L, Allen N, Kaaks R, Bakken K, Lund E, Tjonneland A, et al. Reproductive risk factors and endometrial cancer: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer. 2010; 127:442–51.5. Oerter Klein K. Precocious puberty: who has it? Who should be treated? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999; 84:411–4.6. Cantas-Orsdemir S, Garb JL, Allen HF. Prevalence of cranial MRI findings in girls with central precocious puberty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2018; 31:701–10.7. Chiu CF, Wang CJ, Chen YP, Lo FS. Pathological and incidental findings in 403 Taiwanese girls with central precocious puberty at initial diagnosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020; 11:256.8. Yoon JS, So CH, Lee HS, Lim JS, Hwang JS. Prevalence of pathological brain lesions in girls with central precocious puberty: possible overestimation? J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33:e329.9. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969; 44:291–303.10. Yazdani P, Lin Y, Raman V, Haymond M. A single sample GnRHa stimulation test in the diagnosis of precocious puberty. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2012; 2012:23.11. Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, Ghizzoni L, Palmert MR. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009; 123:e752. –62.12. World Health Organization. Child growth standards [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization;2020. [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/.13. Mughal AM, Hassan N, Ahmed A. Bone age assessment methods: a critical review. Pak J Med Sci. 2014; 30:211.14. Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press;1959.15. Arita K, Kurisu K, Kiura Y, Iida K, Otsubo H. Hypothalamic hamartoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2005; 45:221–31.16. Jung H, Carmel P, Schwartz M, Witkin J, Bentele K, Westphal M, et al. Some hypothalamic hamartomas contain transforming growth factorα, a puberty-inducing growth factor, but not luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999; 84:4695–701.17. Mahachoklertwattana P, Kaplan S, Grumbach M. The luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone-secreting hypothalamic hamartoma is a congenital malformation: natural history. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993; 77:118–24.18. Harrison VS, Oatman O, Kerrigan JF. Hypothalamic hamartoma with epilepsy: review of endocrine comorbidity. Epilepsia. 2017; 58:50–9.19. Rupp D, Molitch M. Pituitary stalk lesions. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008; 15:339–45.20. Wijetilleka S, Khan M, Mon A, Sharma D, Joseph F, Sinha A, et al. Cranial diabetes insipidus with pituitary stalk lesions. QJM. 2016; 109:703–8.21. Kluczyński Ł, Gilis-Januszewska A, Godlewska M, Wójcik M, Zygmunt-Górska A, Starzyk J, et al. Diversity of pathological conditions affecting pituitary stalk. J Clin Med. 2021; 10:1692.22. Brauner R, Adan L, Souberbielle J. Hypothalamic-pituitary function and growth in children with intracranial lesions. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999; 15:662–9.23. Mohn A, Schoof E, Fahlbusch R, Wenzel D, Dörr H. The endocrine spectrum of arachnoid cysts in childhood. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999; 31:316–21.24. Rivarola M, Belgorosky A, Mendilaharzu H, Vidal G. Precocious puberty in children with tumours of the suprasellar and pineal areas: organic central precocious puberty. Acta Paediatr. 2001; 90:751–6.25. Abdolvahabi RM, Mitchell JA, Diaz FG, McAllister JP. A brief review of the effects of chronic hydrocephalus on the gonadotropin releasing hormone system: implications for amenorrhea and precocious puberty. Neurol Res. 2000; 22:123–6.26. Adan L, Bussières L, Dinand V, Zerah M, Pierre-Kahn A, Brauner R. Growth, puberty and hypothalamic-pituitary function in children with suprasellar arachnoid cyst. Eur J Pediatr. 2000; 159:348–55.27. Acharya SV, Gopal RA, Menon PS, Bandgar TR, Shah NS. Precocious puberty due to Rathke cleft cyst in a child. Endocr Pract. 2009; 15:134–7.28. Jung JE, Jin J, Jung MK, Kwon A, Chae HW, Kim DH, et al. Clinical manifestations of Rathke’s cleft cysts and their natural progression during 2 years in children and adolescents. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017; 22:164–9.29. Esiri M. Russell and Rubinstein's pathology of tumors of the nervous system. Sixth edition. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000; 68:538. D.30. Oh YJ, Park HK, Yang S, Song JH, Hwang IT. Clinical and radiological findings of incidental Rathke's cleft cysts in children and adolescents. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 19:20–6.31. Pedicelli S, Alessio P, Scirè G, Cappa M, Cianfarani S. Routine screening by brain magnetic resonance imaging is not indicated in every girl with onset of puberty between the ages of 6 and 8 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014; 99:4455–61.32. Freda PU, Beckers AM, Katznelson L, Molitch ME, Montori VM, Post KD, et al. Pituitary incidentaloma: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011; 96:894–904.33. Chalumeau M, Chemaitilly W, Trivin C, Adan L, Bréart G, Brauner R. Central precocious puberty in girls: an evidence-based diagnosis tree to predict central nervous system abnormalities. Pediatrics. 2002; 109:61–7.34. Harrington J, Palmert MR, Saeger P. Definition, etiology, and evaluation of precocious puberty [Internet]. Waltham (MA): UpToDate, Inc;2012. [cited 2020 May 20]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/definitionetiology-and-evaluation-of-precocious-puberty.35. Kaplowitz PB. Do 6-8 year old girls with central precocious puberty need routine brain imaging? Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2016; 2016:9.36. Mogensen SS, Aksglaede L, Mouritsen A, Sørensen K, Main KM, Gideon P, et al. Pathological and incidental findings on brain MRI in a single-center study of 229 consecutive girls with early or precocious puberty. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e29829.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Commentary on "Pathological brain lesions in girls with central precocious puberty at initial diagnosis in Southern Vietnam"

- Etiology and Age Incidence of Precocious Puberty

- Prevalence of Pathological Brain Lesions in Girls with Central Precocious Puberty: Possible Overestimation?

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Central Precocious Puberty

- Central precocious puberty: is routine brain MRI screening necessary for girls?: Commentary on “Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in central precocious puberty patients: is routine MRI necessary for newly diagnosed patients?”