Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2022 May;26(3):195-205. 10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.3.195.

A simple and novel equation to estimate the degree of bleeding in haemorrhagic shock: mathematical derivation and preliminary in vivo validation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul 03080, Korea

- 2Department of Emergency Medicine, CHA Bundang Medical Center, Seongnam 13496, Korea

- 3Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon 24289, Korea

- 4Department of Critical Care and Emergency Medicine, Mediplex Sejong Hospital, Incheon 21080, Korea

- KMID: 2529402

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.3.195

Abstract

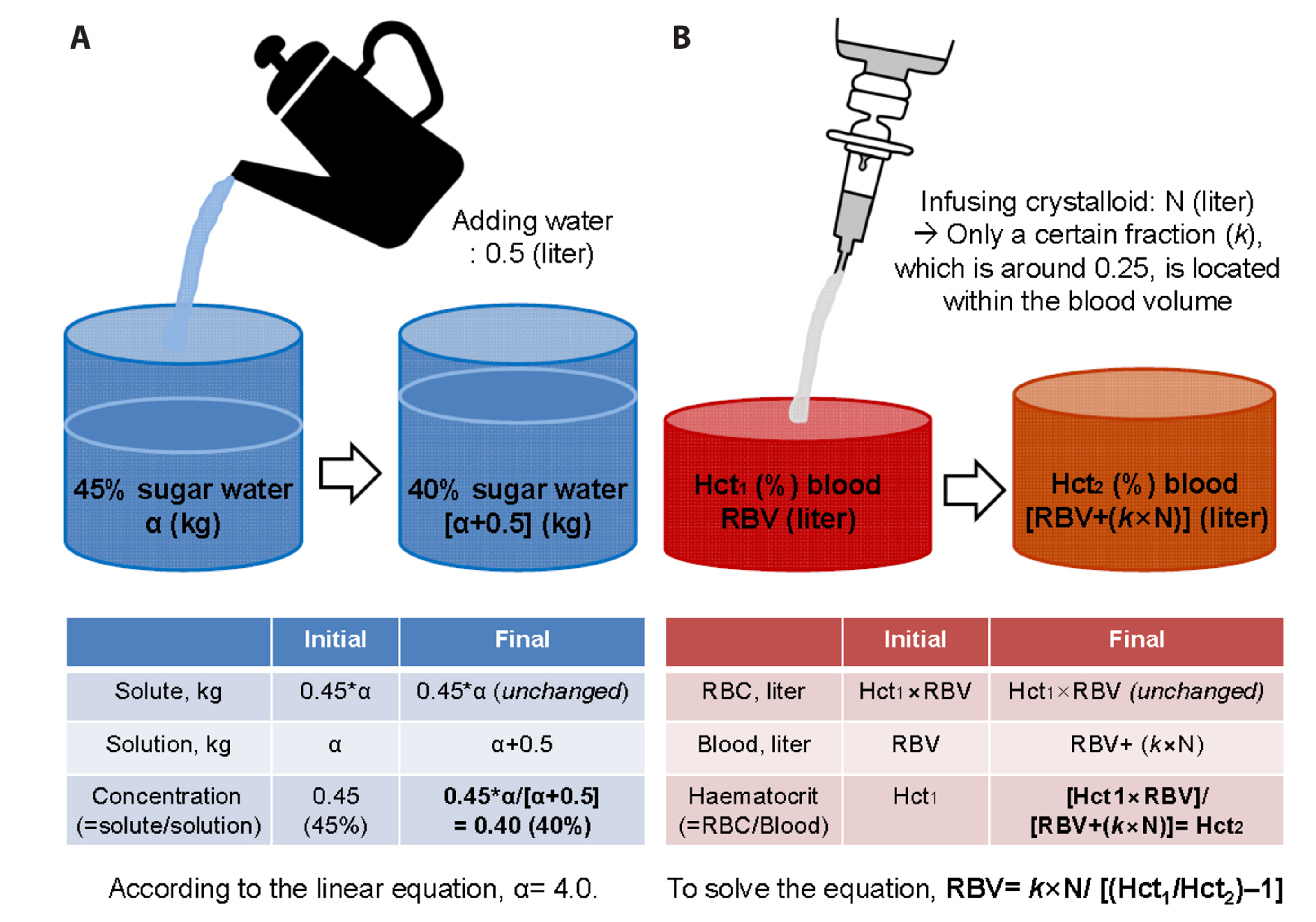

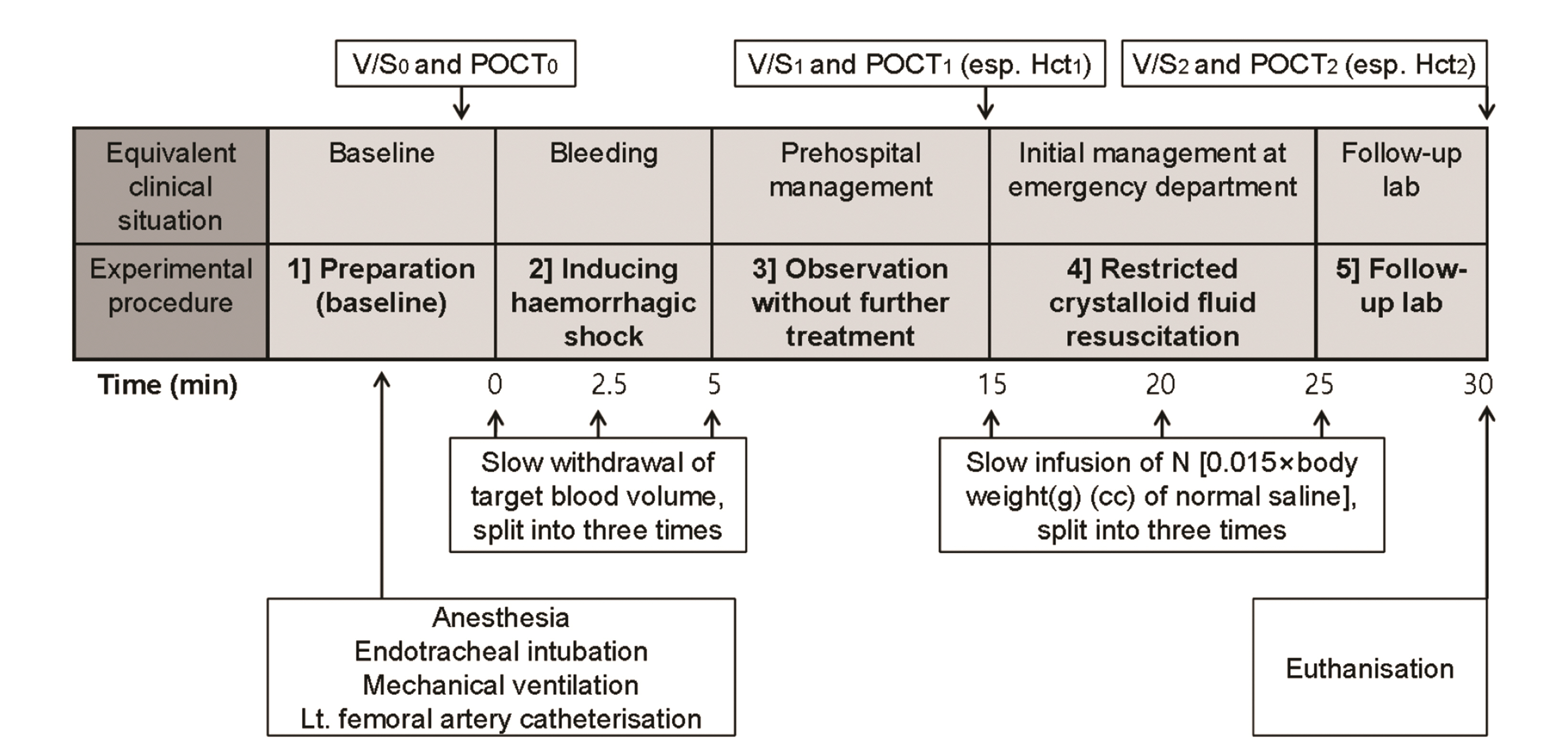

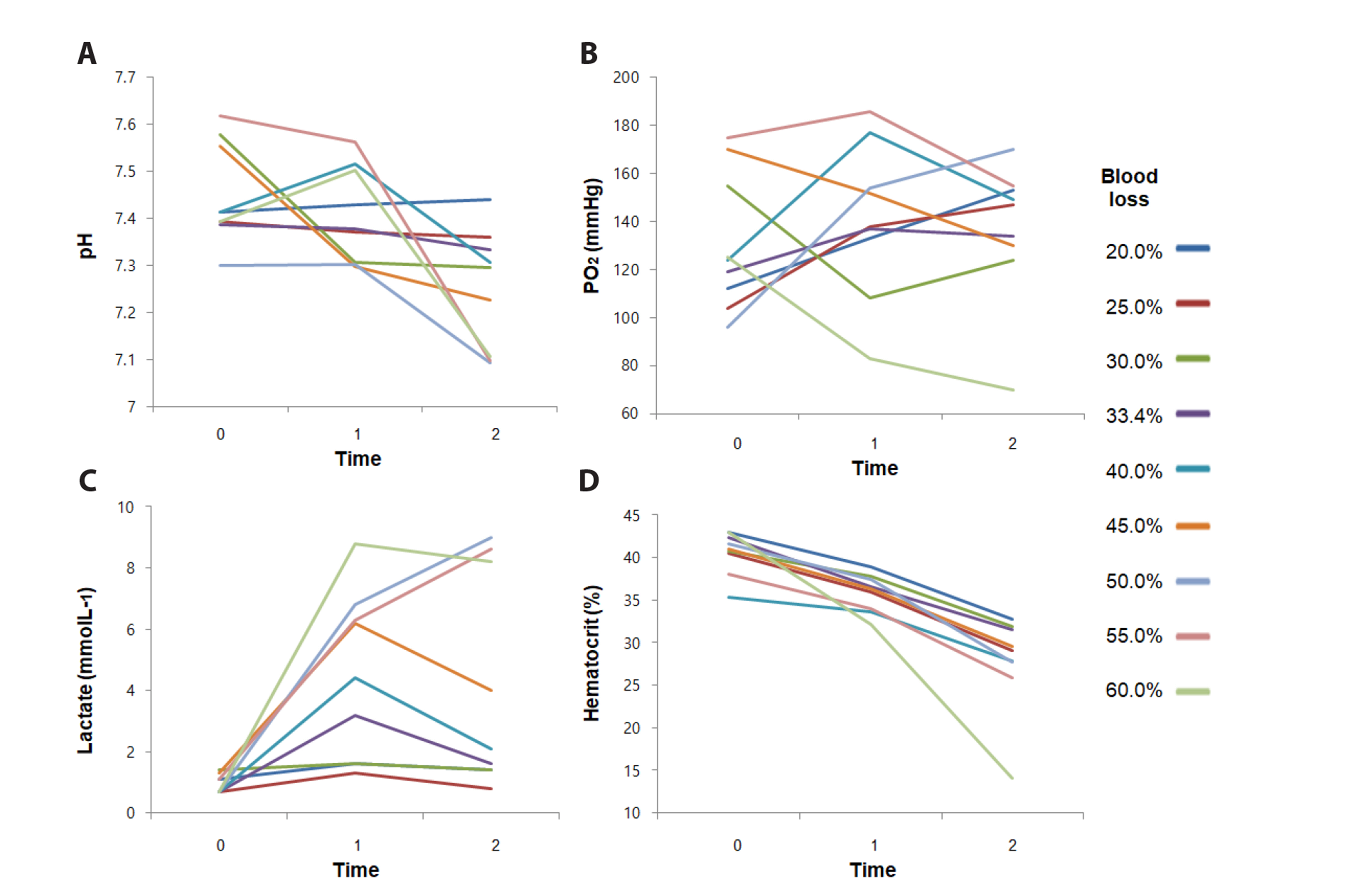

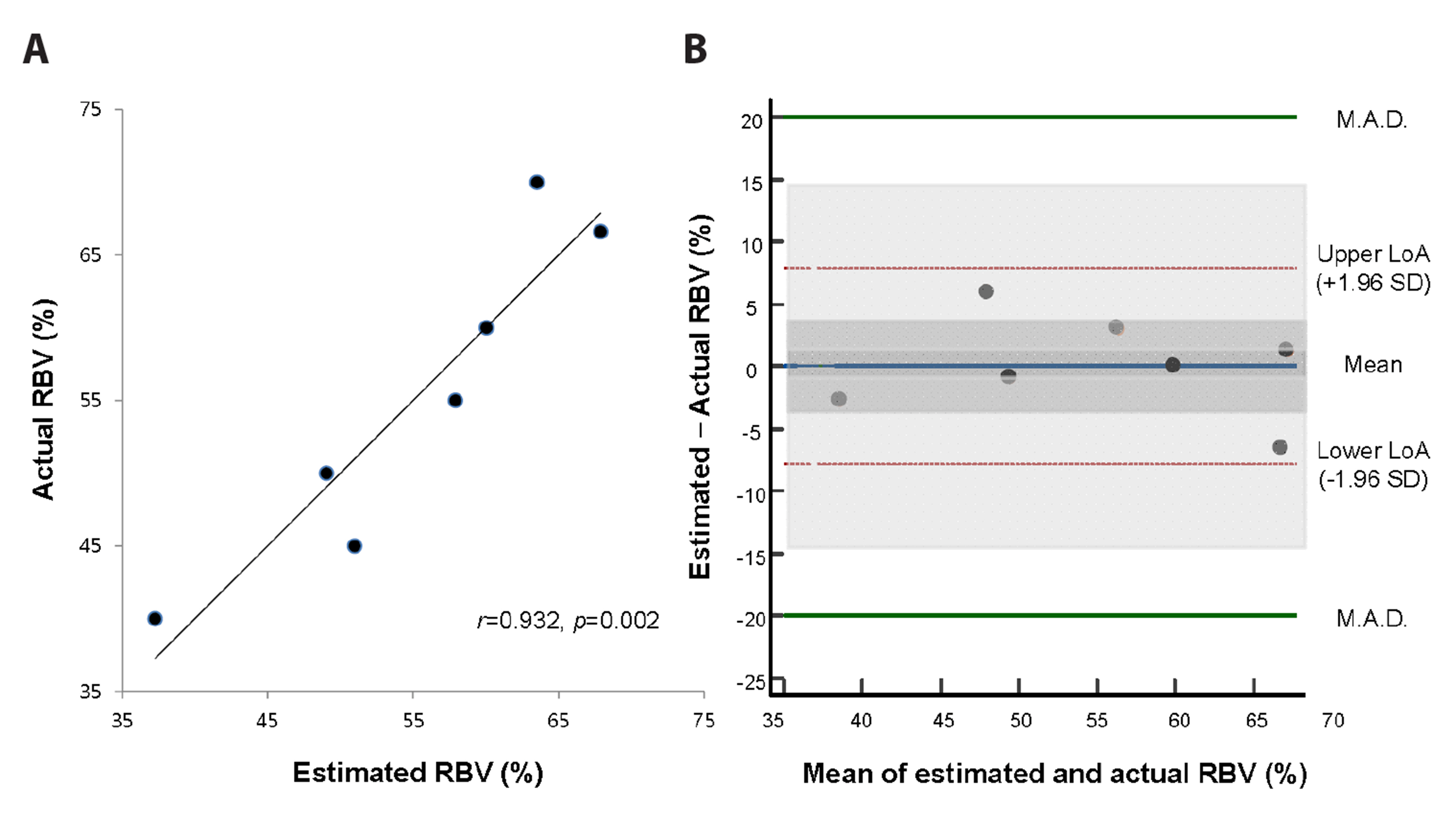

- Determining blood loss [100% – RBV (%)] is challenging in the management of haemorrhagic shock. We derived an equation estimating RBV (%) via serial haematocrits (Hct1 , Hct2 ) by fixing infused crystalloid fluid volume (N) as [0.015 × body weight (g)]. Then, we validated it in vivo. Mathematically, the following estimation equation was derived: RBV (%) = 24k / [(Hct1 / Hct2 ) – 1]. For validation, nonongoing haemorrhagic shock was induced in Sprague–Dawley rats by withdrawing 20.0%–60.0% of their total blood volume (TBV) in 5.0% intervals (n = 9). Hct1 was checked after 10 min and normal saline N cc was infused over 10 min. Hct 2 was checked five minutes later. We applied a linear equation to explain RBV (%) with 1 / [(Hct1 / Hct2 ) – 1]. Seven rats losing 30.0%–60.0% of their TBV suffered shock persistently. For them, RBV (%) was updated as 5.67 / [(Hct1 / Hct2 ) – 1] + 32.8 (95% confidence interval [CI] of the slope: 3.14–8.21, p = 0.002, R2 = 0.87). On a Bland-Altman plot, the difference between the estimated and actual RBV was 0.00 ± 4.03%; the 95% CIs of the limits of agreements were included within the pre-determined criterion of validation (< 20%). For rats suffering from persistent, non-ongoing haemorrhagic shock, we derived and validated a simple equation estimating RBV (%). This enables the calculation of blood loss via information on serial haematocrits under a fixed N. Clinical validation is required before utilisation for emergency care of haemorrhagic shock.

Figure

Reference

-

1. Cannon JW. 2018; Hemorrhagic Shock. N Engl J Med. 378:370–379. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1705649. PMID: 29365303.

Article2. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, et al. 2012; Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 380:2095–2128. Erratum in: Lancet. 2013;381:628. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID: 23245604.3. Tien HC, Spencer F, Tremblay LN, Rizoli SB, Brenneman FD. 2007; Preventable deaths from hemorrhage at a level I Canadian trauma center. J Trauma. 62:142–146. DOI: 10.1097/01.ta.0000251558.38388.47. PMID: 17215745.

Article4. Holcomb JB, del Junco DJ, Fox EE, Wade CE, Cohen MJ, Schreiber MA, Alarcon LH, Bai Y, Brasel KJ, Bulger EM, Cotton BA, Matijevic N, Muskat P, Myers JG, Phelan HA, White CE, Zhang J, Rahbar MH. 2013; The prospective, observational, multicenter, major trauma transfusion (PROMMTT) study: comparative effectiveness of a time-varying treatment with competing risks. JAMA Surg. 148:127–136. DOI: 10.1001/2013.jamasurg.387. PMID: 23560283. PMCID: PMC3740072.

Article5. Barbee RW, Reynolds PS, Ward KR. 2010; Assessing shock resuscitation strategies by oxygen debt repayment. Shock. 33:113–122. DOI: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b8569d. PMID: 20081495.

Article6. Butterworth JF, Mackey DC, Wasnick JD. 2018. Morgan and Mikhail's clinical anesthesiology. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill Education LLC.;New York: DOI: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181b8569d.7. 1980; Recommended methods for measurement of red-cell and plasma volume: International Committee for Standardization in Haematology. J Nucl Med. 21:793–800. PMID: 7400838.8. Falz R, Busse M. 2018; Determination of hemoglobin mass in humans by measurement of CO uptake during inhalation of a CO-air mixture: a proof of concept study. Physiol Rep. 6:e13849. DOI: 10.14814/phy2.13849. PMID: 30178548. PMCID: PMC6121115.

Article9. Plumb JOM, Kumar S, Otto J, Schmidt W, Richards T, Montgomery HE, Grocott MPW. 2018; Replicating measurements of total hemoglobin mass (tHb-mass) within a single day: precision of measurement; feasibility and safety of using oxygen to expedite carbon monoxide clearance. Physiol Rep. 6:e13829. DOI: 10.14814/phy2.13829. PMID: 30203465. PMCID: PMC6131726.

Article10. Callcut RA, Cotton BA, Muskat P, Fox EE, Wade CE, Holcomb JB, Schreiber MA, Rahbar MH, Cohen MJ, Knudson MM, Brasel KJ, Bulger EM, Del Junco DJ, Myers JG, Alarcon LH, Robinson BR. 2013; Defining when to initiate massive transfusion: a validation study of individual massive transfusion triggers in PROMMTT patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 74:59–65. 67–68. discussion 66–67. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182788b34. PMID: 23271078. PMCID: PMC3771339.11. American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma. 2018. Advanced trauma life support: student course manual. 8th ed. American College of Surgeons;Chicago:12. Cotton BA, Dossett LA, Haut ER, Shafi S, Nunez TC, Au BK, Zaydfudim V, Johnston M, Arbogast P, Young PP. 2010; Multicenter validation of a simplified score to predict massive transfusion in trauma. J Trauma. 69 Suppl 1:S33–S39. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e42411. PMID: 20622617.

Article13. Rossaint R, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Coats TJ, Duranteau J, Fernández-Mondéjar E, Filipescu D, Hunt BJ, Komadina R, Nardi G, Neugebauer EA, Ozier Y, Riddez L, Schultz A, Vincent JL, Spahn DR. 2016; The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fourth edition. Crit Care. 20:100. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-016-1265-x. PMID: 27072503. PMCID: PMC4828865.

Article14. Rothermel LD, Lipman JM. 2016; Estimation of blood loss is inaccurate and unreliable. Surgery. 160:946–953. DOI: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.006. PMID: 27544540.

Article15. Dipti A, Soucy Z, Surana A, Chandra S. 2012; Role of inferior vena cava diameter in assessment of volume status: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 30:1414–1419.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.10.017. PMID: 22221934.

Article16. Newgard CD, Cheney TP, Chou R, Fu R, Daya MR, O'Neil ME, Wasson N, Hart EL, Totten AM. 2020; Out-of-hospital circulatory measures to identify patients with serious injury: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 27:1323–1339. DOI: 10.1111/acem.14056. PMID: 32558073.

Article17. Oh WS, Chon SB. 2016; Calculation of the residual blood volume after acute, non-ongoing hemorrhage using serial hematocrit measurements and the volume of isotonic fluid infused: theoretical hypothesis generating study. J Korean Med Sci. 31:814–816. DOI: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.5.814. PMID: 27134507. PMCID: PMC4835611.

Article18. Chang R, Holcomb JB. 2017; Optimal fluid therapy for traumatic hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Clin. 33:15–36. DOI: 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.08.007. PMID: 27894494. PMCID: PMC5131713.

Article19. Imm A, Carlson RW. 1993; Fluid resuscitation in circulatory shock. Crit Care Clin. 9:313–333. DOI: 10.1016/S0749-0704(18)30198-2. PMID: 8490765.

Article20. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, Emerson M, Garner P, Holgate ST, Howells DW, Hurst V, Karp NA, Lazic SE, Lidster K, MacCallum CJ, Macleod M, Pearl EJ, et al. 2020; Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 18:e3000411. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411. PMID: 32663221. PMCID: PMC7360025. PMID: 0cdc6121568245e7b56bd1cca7b31653.

Article21. Ley EJ, Clond MA, Srour MK, Barnajian M, Mirocha J, Margulies DR, Salim A. 2011; Emergency department crystalloid resuscitation of 1.5 L or more is associated with increased mortality in elderly and nonelderly trauma patients. J Trauma. 70:398–400. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318208f99b. PMID: 21307740.

Article22. Lee HB, Blaufox MD. 1985; Blood volume in the rat. J Nucl Med. 26:72–76. PMID: 3965655.23. Moons KG, Kengne AP, Grobbee DE, Royston P, Vergouwe Y, Altman DG, Woodward M. 2012; Risk prediction models: II. External validation, model updating, and impact assessment. Heart. 98:691–698. DOI: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301247. PMID: 22397946.

Article24. Bland JM, Altman DG. 1986; Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1:307–310. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. PMID: 2868172.

Article25. Giavarina D. 2015; Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 25:141–151. DOI: 10.11613/BM.2015.015. PMID: 26110027. PMCID: PMC4470095.

Article26. Chan YH. 2003; Biostatistics 104: correlational analysis. Singapore Med J. 44:614–619. PMID: 14770254.27. Fülöp A, Turóczi Z, Garbaisz D, Harsányi L, Szijártó A. 2013; Experimental models of hemorrhagic shock: a review. Eur Surg Res. 50:57–70. DOI: 10.1159/000348808. PMID: 23615606.

Article28. Lee JH, Kim K, Jo YH, Kim MA, Lee KB, Rhee JE, Doo AR, Lee MJ, Park CJ, Kim J, Chung H. 2014; Blood pressure-targeted stepwise resuscitation for hemorrhagic shock in rats. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 76:771–778. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000106. PMID: 24553547.

Article29. Mayglothling J, Duane TM, Gibbs M, McCunn M, Legome E, Eastman AL, Whelan J, Shah KH. 2012; Emergency tracheal intubation immediately following traumatic injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 73(5 Suppl 4):S333–S340. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827018a5. PMID: 23114490.30. Cotton BA, Jerome R, Collier BR, Khetarpal S, Holevar M, Tucker B, Kurek S, Mowery NT, Shah K, Bromberg W, Gunter OL, Riordan WP Jr. 2009; Guidelines for prehospital fluid resuscitation in the injured patient. J Trauma. 67:389–402. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a8b26f. PMID: 19667896.

Article31. Kwan I, Bunn F, Roberts I. 2003; Timing and volume of fluid administration for patients with bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):CD002245. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002245. PMID: 24599652. PMCID: PMC7133544.

Article32. Shafi S, Collinsworth AW, Richter KM, Alam HB, Becker LB, Bullock MR, Ecklund JM, Gallagher J, Gandhi R, Haut ER, Hickman ZL, Hotz H, McCarthy J, Valadka AB, Weigelt J, Holcomb JB. 2016; Bundles of care for resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock and severe brain injury in trauma patients-Translating knowledge into practice. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 81:780–794. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001161. PMID: 27389129.

Article33. Toll DB, Janssen KJ, Vergouwe Y, Moons KG. 2008; Validation, updating and impact of clinical prediction rules: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 61:1085–1094. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.04.008. PMID: 19208371.

Article34. Hahn RG. 2017; Arterial pressure and the rate of elimination of crystalloid fluid. Anesth Analg. 124:1824–1833. DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002075. PMID: 28452823.

Article35. Hultström M. 2013; Neurohormonal interactions on the renal oxygen delivery and consumption in haemorrhagic shock-induced acute kidney injury. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 209:11–25. DOI: 10.1111/apha.12147. PMID: 23837642.

Article36. Valeri CR, Dennis RC, Ragno G, Macgregor H, Menzoian JO, Khuri SF. 2006; Limitations of the hematocrit level to assess the need for red blood cell transfusion in hypovolemic anemic patients. Transfusion. 46:365–371. DOI: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00730.x. PMID: 16533277.

Article37. Kumar A, Anel R, Bunnell E, Habet K, Zanotti S, Marshall S, Neumann A, Ali A, Cheang M, Kavinsky C, Parrillo JE. 2004; Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure and central venous pressure fail to predict ventricular filling volume, cardiac performance, or the response to volume infusion in normal subjects. Crit Care Med. 32:691–699. DOI: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114996.68110.C9. PMID: 15090949.

Article38. McLean AS. 2016; Echocardiography in shock management. Crit Care. 20:275. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-016-1401-7. PMID: 27543137. PMCID: PMC4992302.

Article39. Thorson CM, Ryan ML, Van Haren RM, Pereira R, Olloqui J, Otero CA, Schulman CI, Livingstone AS, Proctor KG. 2013; Change in hematocrit during trauma assessment predicts bleeding even with ongoing fluid resuscitation. Am Surg. 79:398–406. DOI: 10.1177/000313481307900430. PMID: 23574851.

Article40. Kleinveld DJB, Botros L, Maas MAW, Kers J, Aman J, Hollmann MW, Juffermans NP. 2021; Bosutinib reduces endothelial permeability and organ failure in a rat polytrauma transfusion model. Br J Anaesth. 126:958–966. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.01.032. PMID: 33685634. PMCID: PMC8258973.

Article41. Rahbar E, Cardenas JC, Baimukanova G, Usadi B, Bruhn R, Pati S, Ostrowski SR, Johansson PI, Holcomb JB, Wade CE. 2015; Endothelial glycocalyx shedding and vascular permeability in severely injured trauma patients. J Transl Med. 13:117. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-015-0481-5. PMID: 25889764. PMCID: PMC4397670.

Article42. White NJ, Ward KR, Pati S, Strandenes G, Cap AP. 2017; Hemorrhagic blood failure: oxygen debt, coagulopathy, and endothelial damage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 82(6S Suppl 1):S41–S49. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001436. PMID: 28328671. PMCID: PMC5488798.43. Hamon A, Mokart D, Pouliquen C, Guibert JM, Cambon S, Duong LN, Lambaudie E, Sannini A, Chow-Chine L, Bisbal M, Ewald J, Turrini O, Faucher M. 2020; Intraoperative hemorrhagic shock in cancer surgical patients: short and long-term mortality and associated factors. Shock. 54:659–666. DOI: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001537. PMID: 32205792.

Article44. Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Mélot C, Vincent JL. 2001; Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 286:1754–1758. DOI: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. PMID: 11594901.

Article45. Minne L, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E. 2008; Evaluation of SOFA-based models for predicting mortality in the ICU: a systematic review. Crit Care. 12:R161. DOI: 10.1186/cc7160. PMID: 19091120. PMCID: PMC2646326.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Simple mathematical formulae for estimation of median values of fetal biometry at each gestational age

- Mathematical Explanation for the Wide and Deviated Range of Optimal Hematocrit

- Mathematical model for early functional recovery pattern of kidney transplant recipients using serum creatinine

- Development and Cross-Validation of Equation for Estimating Percent Body Fat of Korean Adults According to Body Mass Index

- Prediction of vasopressor requirement among hypotensive patients with suspected infection: usefulness of diastolic shock index and lactate