J Korean Med Sci.

2022 Apr;37(16):e122. 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e122.

Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score and the Modified Early Warning Score for Predicting Clinical Deterioration in General Ward Patients Regardless of Suspected Infection

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Critical Care Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2VUNO, Seoul, Korea

- 3Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 4Department of Critical Care and Emergency Medicine, Mediplex Sejong Hospital, Incheon, Korea

- 5Division of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Center, Mediplex Sejong Hospital, Incheon, Korea

- 6Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Hospital Medicine, Inha University Hospital, Inha University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

- 7Department of Emergency Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 8Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2529290

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e122

Abstract

- Background

The quick sequential organ failure assessment (qSOFA) score is suggested to use for screening patients with a high risk of clinical deterioration in the general wards, which could simply be regarded as a general early warning score. However, comparison of unselected admissions to highlight the benefits of introducing qSOFA in hospitals already using Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) remains unclear. We sought to compare qSOFA with MEWS for predicting clinical deterioration in general ward patients regardless of suspected infection.

Methods

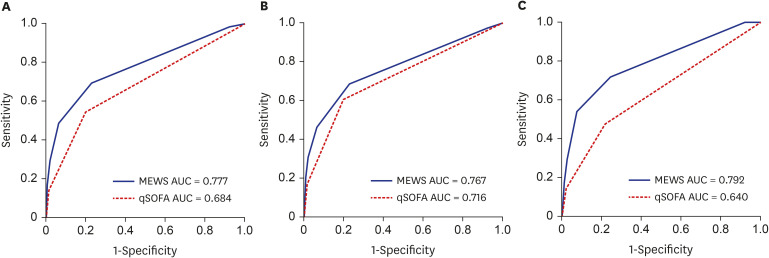

The predictive performance of qSOFA and MEWS for in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) or unexpected intensive care unit (ICU) transfer was compared with the areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) analysis using the databases of vital signs collected from consecutive hospitalized adult patients over 12 months in five participating hospitals in Korea.

Results

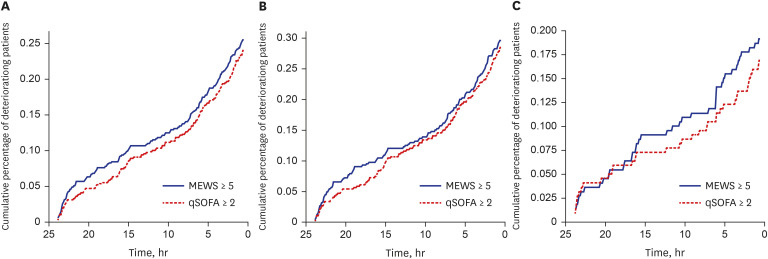

Of 173,057 hospitalized patients included for analysis, 668 (0.39%) experienced the composite outcome. The discrimination for the composite outcome for MEWS (AUC, 0.777; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.770–0.781) was higher than that for qSOFA (AUC, 0.684; 95% CI, 0.676–0.686; P < 0.001). In addition, MEWS was better for prediction of IHCA (AUC, 0.792; 95% CI, 0.781–0.795 vs. AUC, 0.640; 95% CI, 0.625–0.645; P < 0.001) and unexpected ICU transfer (AUC, 0.767; 95% CI, 0.760–0.773 vs. AUC, 0.716; 95% CI, 0.707–0.718; P < 0.001) than qSOFA. Using the MEWS at a cutoff of ≥ 5 would correctly reclassify 3.7% of patients from qSOFA score ≥ 2. Most patients met MEWS ≥ 5 criteria 13 hours before the composite outcome compared with 11 hours for qSOFA score ≥ 2.

Conclusion

MEWS is more accurate that qSOFA score for predicting IHCA or unexpected ICU transfer in patients outside the ICU. Our study suggests that qSOFA should not replace MEWS for identifying patients in the general wards at risk of poor outcome.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Winslow C, Robicsek AA, Meltzer DO, Gibbons RD, et al. Multicenter development and validation of a risk stratification tool for ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014; 190(6):649–655. PMID: 25089847.2. Escobar GJ, LaGuardia JC, Turk BJ, Ragins A, Kipnis P, Draper D. Early detection of impending physiologic deterioration among patients who are not in intensive care: development of predictive models using data from an automated electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2012; 7(5):388–395. PMID: 22447632.3. Kause J, Smith G, Prytherch D, Parr M, Flabouris A, Hillman K, et al. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom--the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004; 62(3):275–282. PMID: 15325446.4. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Edelson DP. Risk stratification of hospitalized patients on the wards. Chest. 2013; 143(6):1758–1765. PMID: 23732586.5. Umscheid CA, Betesh J, VanZandbergen C, Hanish A, Tait G, Mikkelsen ME, et al. Development, implementation, and impact of an automated early warning and response system for sepsis. J Hosp Med. 2015; 10(1):26–31. PMID: 25263548.6. Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, Gemmel L. Validation of a Modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001; 94(10):521–526. PMID: 11588210.7. Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, Soule J, Whippy A, Angus DC, et al. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014; 312(1):90–92. PMID: 24838355.8. Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A, et al. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016; 315(8):762–774. PMID: 26903335.9. Levy MM, Evans LE, Rhodes A. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46(6):997–1000. PMID: 29767636.10. Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017; 43(3):304–377. PMID: 28101605.11. Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. Review and performance evaluation of aggregate weighted ‘track and trigger’ systems. Resuscitation. 2008; 77(2):170–179. PMID: 18249483.12. Smith ME, Chiovaro JC, O’Neil M, Kansagara D, Quiñones AR, Freeman M, et al. Early warning system scores for clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014; 11(9):1454–1465. PMID: 25296111.13. Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021; 49(11):e1063–e1143. PMID: 34605781.14. Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, Sokol S, Pettit N, Howell MD, et al. Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, and Early Warning Scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017; 195(7):906–911. PMID: 27649072.15. Churpek MM, Snyder A, Sokol S, Pettit NN, Edelson DP. Investigating the impact of different suspicion of infection criteria on the accuracy of quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, and Early Warning Scores. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(11):1805–1812. PMID: 28737573.16. American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support Course for Physicians. Chicago, IL, USA: American College of Surgeons;1989.17. Kelly CA, Upex A, Bateman DN. Comparison of consciousness level assessment in the poisoned patient using the alert/verbal/painful/unresponsive scale and the Glasgow Coma Scale. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 44(2):108–113. PMID: 15278081.18. Redfern OC, Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Meredith P, Inada-Kim M, Schmidt PE. A comparison of the quick sequential (sepsis-related) organ failure assessment score and the National Early Warning Score in non-ICU patients with/without infection. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46(12):1923–1933. PMID: 30130262.19. Lo RS, Leung LY, Brabrand M, Yeung CY, Chan SY, Lam CC, et al. qSOFA is a poor predictor of short-term mortality in all patients: a systematic review of 410,000 patients. J Clin Med. 2019; 8(1):E61. PMID: 30626160.20. Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, Bellomo R, Brown D, Doig G, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005; 365(9477):2091–2097. PMID: 15964445.21. Song JU, Suh GY, Park HY, Lim SY, Han SG, Kang YR, et al. Early intervention on the outcomes in critically ill cancer patients admitted to intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2012; 38(9):1505–1513. PMID: 22592633.22. Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982; 143(1):29–36. PMID: 7063747.23. Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008; 27(2):157–172. PMID: 17569110.24. Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Huber MT, Park SY, Hall JB, Edelson DP. Predicting cardiac arrest on the wards: a nested case-control study. Chest. 2012; 141(5):1170–1176. PMID: 22052772.25. Smith GB, Prytherch DR, Meredith P, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI. The ability of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) to discriminate patients at risk of early cardiac arrest, unanticipated intensive care unit admission, and death. Resuscitation. 2013; 84(4):465–470. PMID: 23295778.26. Jones DA, DeVita MA, Bellomo R. Rapid-response teams. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365(2):139–146. PMID: 21751906.27. Ludikhuize J, Smorenburg SM, de Rooij SE, de Jonge E. Identification of deteriorating patients on general wards; measurement of vital parameters and potential effectiveness of the Modified Early Warning Score. J Crit Care. 2012; 27(4):424.e7–424.13.28. Clifton DA, Clifton L, Sandu DM, Smith GB, Tarassenko L, Vollam SA, et al. ‘Errors’ and omissions in paper-based early warning scores: the association with changes in vital signs--a database analysis. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(7):e007376.29. Shappell C, Snyder A, Edelson DP, Churpek MM. American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation Investigators. Predictors of in-hospital mortality after rapid response team calls in a 274 hospital nationwide sample. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46(7):1041–1048. PMID: 29293147.30. Ahn JH, Jung YK, Lee JR, Oh YN, Oh DK, Huh JW, et al. Predictive powers of the Modified Early Warning Score and the National Early Warning Score in general ward patients who activated the medical emergency team. PLoS One. 2020; 15(5):e0233078. PMID: 32407344.31. Serafim R, Gomes JA, Salluh J, Póvoa P. A comparison of the quick-SOFA and Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome criteria for the diagnosis of sepsis and prediction of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2018; 153(3):646–655. PMID: 29289687.32. Singer AJ, Ng J, Thode HC Jr, Spiegel R, Weingart S. Quick SOFA scores predict mortality in adult emergency department patients with and without suspected infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2017; 69(4):475–479. PMID: 28110990.33. Liu VX, Lu Y, Carey KA, Gilbert ER, Afshar M, Akel M, et al. Comparison of Early Warning Scoring Systems for hospitalized patients with and without infection at risk for in-hospital mortality and transfer to the intensive care unit. JAMA Netw Open. 2020; 3(5):e205191. PMID: 32427324.34. Jarvis SW, Kovacs C, Briggs J, Meredith P, Schmidt PE, Featherstone PI, et al. Are observation selection methods important when comparing early warning score performance? Resuscitation. 2015; 90:1–6. PMID: 25668311.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Modified quick-SOFA score: Can it enhance prognostic assessment for hospitalized patients with chronic liver diseases?: Editorial on “Dynamic analysis of acute deterioration in chronic liver disease patients using modified quick sequential organ failure assessment”

- A comparison of scoring systems for predicting mortality and sepsis in the emergency department patients with a suspected infection

- Use of the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale for poor outcome prediction among emergency department patients with suspected infection

- Prognostic Accuracy of the Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment for Outcomes Among Patients with Trauma in the Emergency Department: A Comparison with the Modified Early Warning Score, Revised Trauma Score, and Injury Severity Score

- Derivation and validation of modified early warning score plus SpO2/FiO2 score for predicting acute deterioration of patients with hematological malignancies