Korean Circ J.

2022 Apr;52(4):265-279. 10.4070/kcj.2022.0014.

Reimbursement of Digital Therapeutics: Future Perspectives in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1HIRA Research Institute, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service, Wonju, Korea

- 2Public Healthcare Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2528021

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2022.0014

Abstract

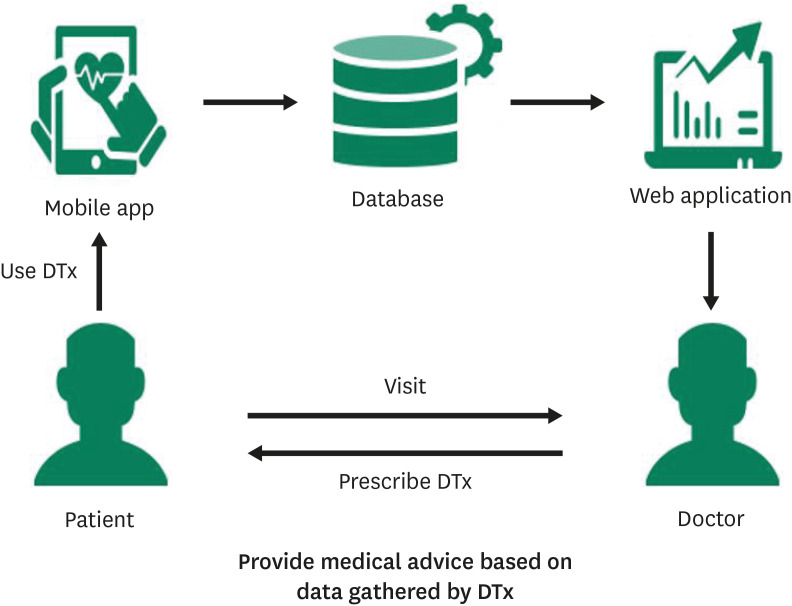

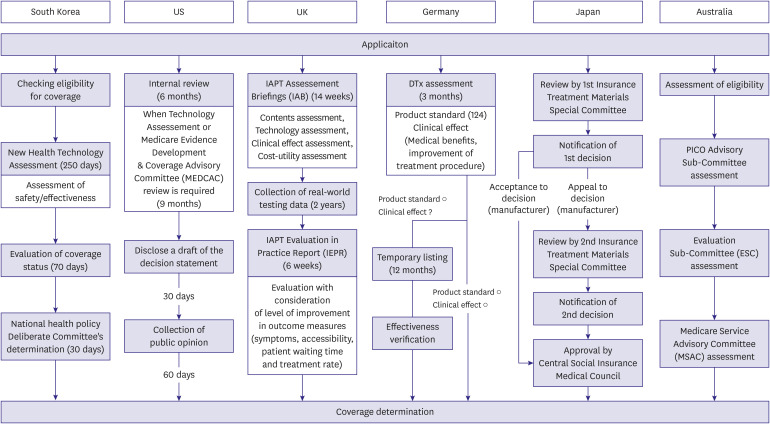

- Digital health is rapidly growing worldwide and its area is expanding from wellness to treatment due to digital therapeutics (DTx). This study compared DTx in the Korean context with other countries to better understand its political and practical implications. DTx is generally the same internationally, often categorized as software as a medical device. It provides evidence-based therapeutic interventions for medical disabilities and diseases. Abroad, DTx support entailed state subsidies and fundraising and national health insurance coverage. In the case of national health insurance coverage, most cases were applied to mental diseases. Moreover, in Japan, DTx related to hypertension will possibly be under discussion for national health insurance coverage in 2022. In overseas countries, coverage was decided only when the clinical effects were equivalent to those provided by existing technology, and in the UK, real usage data for DTx and associated evaluations were reflected by national health coverage determination. Prices were either determined through closed negotiations with health insurance operating agencies and manufacturers or established based on existing technology. Concerning the current situation, DTx dealing with various diseases including hypertension are expected to be developed near in the future, and the demand for use and compensation will likely increase. Therefore, it is urgent to define and prepare for DTx, relevant support systems, and health insurance coverage listings. Several support systems must be considered, including government subsidies, science/technology funds, and health insurance.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Rapid transition to digital healthcare and the role of oral and maxillofacial surgeons

Jung-Woo Lee

J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;48(5):247-248. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2022.48.5.247.

Reference

-

1. Pear Therapeutics, Inc. Pear therapeutics press release [Internet]. Boston (MA): Pear Therapeutics;2021. cited 2021 September 22. Available from: https://peartherapeutics.com/fda-obtains-fda-clearance-first-prescription-digital-therapeutic-treat-disease/.2. Golinelli D, Boetto E, Carullo G, Nuzzolese AG, Landini MP, Fantini MP. Adoption of digital technologies in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of early scientific literature. J Med Internet Res. 2020; 22:e22280. PMID: 33079693.

Article3. Kataria S, Ravindran V. Digital health: a new dimension in rheumatology patient care. Rheumatol Int. 2018; 38:1949–1957. PMID: 29713795.

Article4. Kim HS. Apprehensions about excessive belief in digital therapeutics: points of concern excluding merits. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35:e373. PMID: 33230984.

Article5. Shim JS, Oh K, Jung SJ, Kim HC. Self-reported diet management and adherence to dietary guidelines in Korean adults with hypertension. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:432–440. PMID: 32096363.

Article6. Cheung BMY, Or B, Fei Y, Tsoi MF. A 2020 vision of hypertension. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:469–475. PMID: 32281321.

Article7. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Enforcement policy for digital health devices for treating psychiatric disorders during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) public health emergency [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration;2020. cited 2021 March 27. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.8. Gesetzesbeschluss des Deutschen Bundestages (Legislature, German Federal Parliament). Gesetz für eine bessere Versorgung durch Digitalisierung und Innovation (Digitale-Versorgung-Gesetz - DVG) (Nov. 29, 2019).9. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Guidelines on review and approval of digital therapeutics [Internet]. Cheongju: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety;2020. cited 2021 March 27. Available from: https://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/brd/m_40/view.do?seq=72624&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&multi_itm_seq=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=1.10. Digital Therapeutics Alliance. Digital therapeutics definition and core principles [Internet]. place unknown: Digital Therapeutics Alliance;2019. cited 2021 March 27. Available from: https://dtxalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/DTA_DTx-Definition-and-Core-Principles.pdf.11. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte. DiGA [Internet]. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte;2021. cited 2021 May 27. Available from: https://diga.bfarm.de/.12. CureApp, Inc. CureApp hypertension therapeutics app clinical trial results announced at ESC congress 2021 and published in the European Heart Journal, a leading cardiovascular journal [Internet]. Tokyo: CureApp, Inc.;2021. cited 2021 September 22. Available from: https://cureapp-en.blogspot.com/.13. Jeon YW, Kim HC. Factors associated with awareness, treatment, and control rate of hypertension among Korean young adults aged 30–49 years. Korean Circ J. 2020; 50:1077–1091. PMID: 32975054.

Article14. Lee HY, Oh GC, Sohn IS, et al. Suboptimal management status of younger hypertensive population in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2021; 51:598–606. PMID: 34085433.

Article15. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte. The fast-track process for digital health applications (DiGA) according to section 139e SGB V [Internet]. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte;2020. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.bfarm.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/MedicalDevices/DiGA_Guide.html.16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Policy for device software functions and mobile medical applications [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration;2019. cited 2021 March 27. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/80958/download.17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;2019. cited 2021 March 27. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/our-programmes/evidence-standards-framework/digital-evidence-standards-framework.pdf.18. National Health Services. NHS mental health implementation plan 2019/20-2023/24 [Internet]. London: National Health Services;2019. cited 2021 March 27. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/nhs-mental-health-implementation-plan-2019-20-2023-24.pdf.19. National Health Services. The improving access to psychological therapies manual [Internet]. London: National Health Services;2018. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/the-iapt-manual-v5.pdf.20. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Guidelines for medical device applicability of the program [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2021. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11120000/000764274.pdf.21. Australian Therapeutic Goods Act 1989, Pub. L. No. 21, 1990 (Jan 1, 2019).22. Therapeutic Goods Administration. How the TGA regulates software based medical devices [Internet]. Woden: Therapeutic Goods Administration;2021. cited 2021 April 20. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/how-tga-regulates-software-based-medical-devices.pdf.23. National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency. Guidance to new healthcare technology evaluation system A to Z [Internet]. Seoul: National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency;2020. cited 2021 May 25. Available from: https://nhta.neca.re.kr/nhta/publication/nhtaU0605V.ecg?seq=8975.24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technology (MCIT) and definition of “Reasonable and Necessary”; Delay of effective date. Final rules. Fed Regist. 2021; 86:26849–26854.25. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technology (MCIT) and definition of “Reasonable and Necessary.” Final rules. Fed Regist. 2021; 86:2987–3010.26. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technology (MCIT) and definition of “Reasonable and Necessary.” Final rules. Fed Regist. 2021; 86:62944–62958.27. National Health Services. Test beds programme information to support the launch of wave 2 [Internet]. London: National Health Services;2018. cited 2021 April 21. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/test-beds-supporting-information-wave-2-competition.pdf.28. National Health Services. MedTech funding mandate policy 2021/22 [Internet]. London: National Health Services;2021. cited 2021 April 21. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/aac/wp-content/uploads/sites/50/2021/01/mtfm-policy-guidance-jan-2021.pdf.29. National Health Services. 2020/21 National tariff payment system [Internet]. London: National Health Services;2020. cited 2021 April 21. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/20-21_National-Tariff-Payment-System.pdf.30. Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Innovationsausschuss. Forderbekanntmachung Seite des Innovationsausschusses beim Gemeinsamen Bundesausschuss zur themenoffenen Forderung von neuen Versorgungsformen gemaß § 92a Absatz 1 des Fuften Buches Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB V) zur Weiterentwicklung der Versorgung in der gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung (zweistufiges Verfahren) [Internet]. Berlin: Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Innovationsausschuss;2021. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://innovationsfonds.g-ba.de/downloads/media/245/2021-03-17_Foerderbekanntmachung_NVF_themenoffen_2021.pdf.31. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. DX (Digital Transformation) action strategies in healthcare for SaMD (Software as a Medical Device) [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2020. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11124500/000737470.pdf.32. Australian Government, Australian Digital Health Agency. Australia’s national digital health strategy [Internet]. Sydney: Australian Digital Health Agency;2017. cited 2021 May 25. Available from: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-08/apo-nid182181.pdf.33. University of Canberra. Mobile health: empowering people with type 2 diabetes using digital tools [Internet]. Canberra: University of Canberra;2016. cited 2021 November 23. Available from: https://www.canberra.edu.au/research/faculty-research-centres/nmrc/research/mobile-digital-communication-and-health-management/Mobile-Health-Empowering-people-with-type-2-diabetes-using-digital-tools-updated-v2.pdf.34. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Roles and functions of health insurance review and assessment service [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2021. cited 2021 May 25. Available from: https://repository.hira.or.kr/handle/2019.oak/2523.35. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Guidelines on national health insurance benefits coverage for new and innovative healthcare technology. AI-based healthcare technology (medical imaging) & introduction of 3D printing to healthcare technology [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service;2019. cited 2021 May 25. Available from: https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020041000100&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=10255#none.36. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; revised process for making national coverage determinations. Notice. Fed Regist. 2013; 78:48164–48169.37. Premera Blue Cross. Medical policy-13.012.500. Prescription digital therapeutics [Internet]. Mountlake Terrace (WA): Premera Blue Cross;2021. cited 2021 November 23. Available from: https://www.premera.com/medicalpolicies/13.01.500.pdf.38. UK Department of Health and Social Care. Accelerated access review. Final report [Internet]. London: UK Department of Health and Social Care;2016. cited 2021 May 20. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/565072/AAR_final.pdf.39. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Process and methods statement for the production of NICE IAPT assessment briefings (IABs) [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;2019. cited 2021 May 20. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-advice/IAPT/IAB-process-and-methods-statement.pdf.40. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Process and methods statement for the production of NICE IAPT evaluation in practice reports [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;2019. cited 2021 May 20. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-advice/IAPT/IEPR-process-methods.pdf.41. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Space from depression for treating adults with depression [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence;2020. cited 2021 May 20. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib215/resources/space-from-depression-for-treating-adults-with-depression-pdf-2285965453227973.42. Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte. DiGA directory [Internet]. Bonn: Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte;2021. cited 2021 May 27. Available from: https://diga.bfarm.de/de/verzeichnis.43. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Handling of medical device insurance coverage, etc. [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2019. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000497471.pdf.44. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Criteria for calculating insurance redemption prices for specified insurance medical materials [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2019. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000497470.pdf.45. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Insurance coverage for medical devices [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan;2020. cited 2021 April 13. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12404000/000693018.pdf.46. CureApp, Inc. CureApp and Jichi Medical University collaborate on a hypertension therapeutics app Primary endpoint met in Phase III clinical trial in Japan. [Internet]. Tokyo: CureApp, Inc.;2021. cited 2021 December 2. Available from: https://cureapp-en.blogspot.com/2021/03/cureapp-and-jichi-medical-university.html.47. Medicare Services Advisory Committee. Frequently asked questions [Internet]. place unknown: Medicare Services Advisory Committee;2019. cited 2021 June 1. Available from: http://www.msac.gov.au/internet/msac/publishing.nsf/Content/FAQ-01.48. Medicare Services Advisory Committee. Process framework [Internet]. place unknown: Medicare Services Advisory Committee;2016. cited 2021 May 25. Available from: http://www.msac.gov.au/internet/msac/publishing.nsf/Content/FFDFEFDA8B25248FCA25801000123AD3/$File/Final%20Process%20Framework.pdf.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Current trends and future perspectives on digital therapeutics

- The Metaverse for Healthcare: Trends, Applications, and Future Directions of Digital Therapeutics for Urology

- Introduction to Digital Therapeutics

- Current Status and Future Directions of Digital Therapeutics for Insomnia

- Digital Therapeutics in Hearing Healthcare: Evidence-Based Review