J Stroke.

2022 Jan;24(1):21-40. 10.5853/jos.2021.02831.

Hypertriglyceridemia: A Neglected Risk Factor for Ischemic Stroke?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pharmacology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Beijing, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Molecular Cardiovascular Sciences, Ministry of Education, Beijing, China

- 3State Key Laboratory of Natural and Biomimetic Drugs, Beijing, China

- 4NHC Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Molecular Biology and Regulatory Peptides, Beijing, China

- 5Beijing Key Laboratory of Molecular Pharmaceutics and New Drug Delivery Systems, Peking University Health Science Center, Beijing, China

- KMID: 2525328

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2021.02831

Abstract

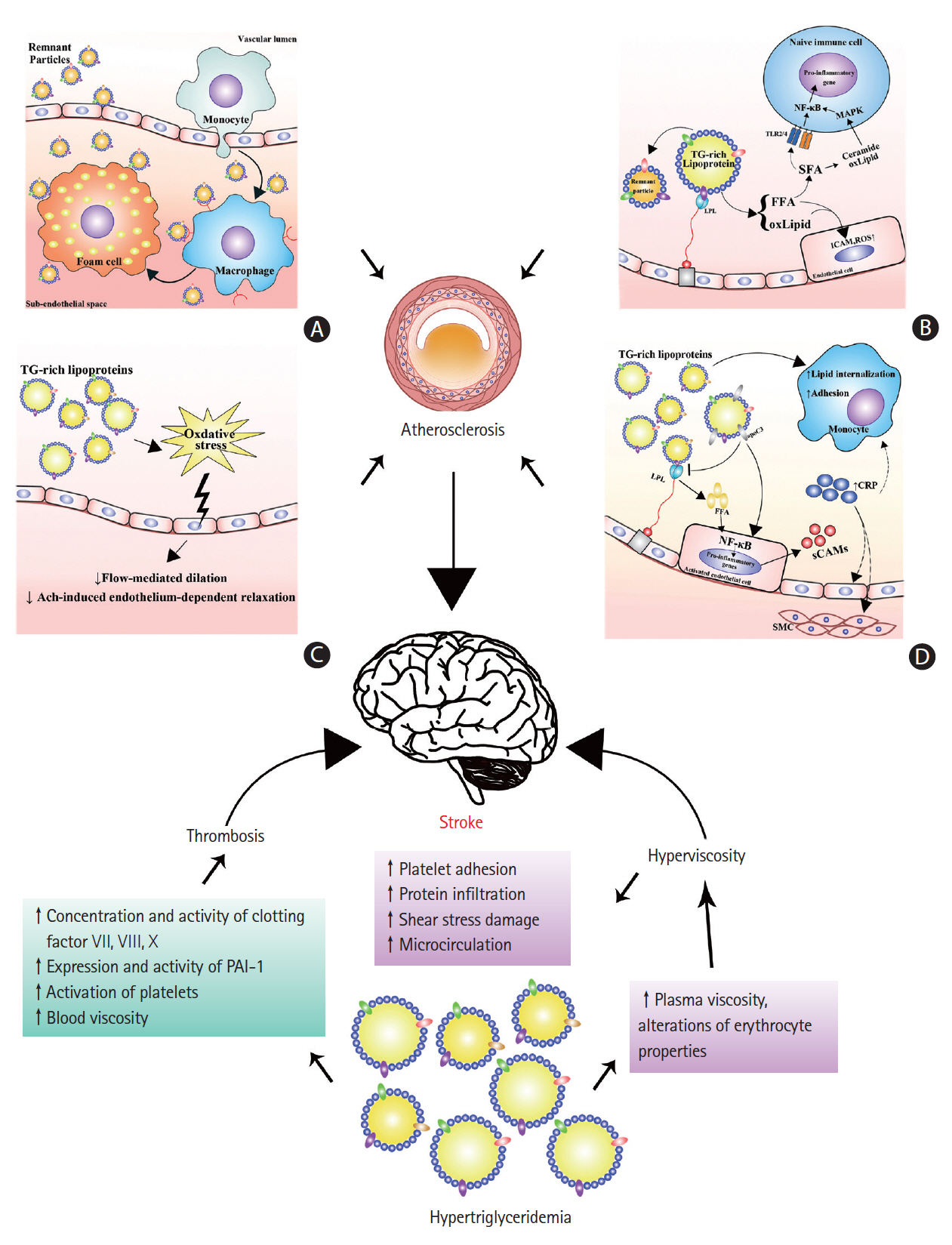

- Hypertriglyceridemia is caused by defects in triglyceride metabolism and generally manifests as abnormally high plasma triglyceride levels. Although the role of hypertriglyceridemia may not draw as much attention as that of plasma cholesterol in stroke, plasma triglycerides, especially nonfasting triglycerides, are thought to be correlated with the risk of ischemic stroke. Hypertriglyceridemia may increase the risk of ischemic stroke by promoting atherosclerosis and thrombosis and increasing blood viscosity. Moreover, hypertriglyceridemia may have some protective effects in patients who have already suffered a stroke via unclear mechanisms. Therefore, further studies are needed to elucidate the role of hypertriglyceridemia in the development and prognosis of ischemic stroke.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Campbell BC, De Silva DA, Macleod MR, Coutts SB, Schwamm LH, Davis SM, et al. Ischaemic stroke. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019; 5:70.

Article2. Kuriakose D, Xiao Z. Pathophysiology and treatment of stroke: present status and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21:7609.

Article3. Goldstein LB, Bushnell CD, Adams RJ, Appel LJ, Braun LT, Chaturvedi S, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011; 42:517–584.

Article4. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45:2160–2236.5. Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1238–1251.6. Röther J, Alberts MJ, Touzé E, Mas JL, Hill MD, Michel P, et al. Risk factor profile and management of cerebrovascular patients in the REACH Registry. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008; 25:366–374.

Article7. Glasser SP, Mosher A, Howard G, Banach M. What is the association of lipid levels and incident stroke? Int J Cardiol. 2016; 220:890–894.

Article8. Sun L, Clarke R, Bennett D, Guo Y, Walters RG, Hill M, et al. Causal associations of blood lipids with risk of ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage in Chinese adults. Nat Med. 2019; 25:569–574.

Article9. Stamler J, Neaton JD, Cohen JD, Cutler J, Eberly L, Grandits G, et al. Multiple risk factor intervention trial revisited: a new perspective based on nonfatal and fatal composite endpoints, coronary and cardiovascular, during the trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012; 1:e003640.

Article10. Castilla-Guerra L, Fernández-Moreno Mdel C, López-Chozas JM. Statins in the secondary prevention of stroke: new evidence from the SPARCL Study. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2016; 28:202–208.11. Tramacere I, Boncoraglio GB, Banzi R, Del Giovane C, Kwag KH, Squizzato A, et al. Comparison of statins for secondary prevention in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2019; 17:67.

Article12. Aznaouridis K, Masoura C, Vlachopoulos C, Tousoulis D. Statins in stroke. Curr Med Chem. 2019; 26:6174–6185.

Article13. Hindy G, Engström G, Larsson SC, Traylor M, Markus HS, Melander O, et al. Role of blood lipids in the development of ischemic stroke and its subtypes: a Mendelian randomization study. Stroke. 2018; 49:820–827.14. Holmes MV, Millwood IY, Kartsonaki C, Hill MR, Bennett DA, Boxall R, et al. Lipids, lipoproteins, and metabolites and risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71:620–632.

Article15. Hassing HC, Surendran RP, Mooij HL, Stroes ES, Nieuwdorp M, Dallinga-Thie GM. Pathophysiology of hypertriglyceridemia. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012; 1821:826–832.

Article16. Imaizumi K, Fainaru M, Havel RJ. Composition of proteins of mesenteric lymph chylomicrons in the rat and alterations produced upon exposure of chylomicrons to blood serum and serum proteins. J Lipid Res. 1978; 19:712–722.

Article17. Zilversmit DB. Atherogenesis: a postprandial phenomenon. Circulation. 1979; 60:473–485.

Article18. Cooper AD. Hepatic uptake of chylomicron remnants. J Lipid Res. 1997; 38:2173–2192.

Article19. Mahley RW, Huang Y. Atherogenic remnant lipoproteins: role for proteoglycans in trapping, transferring, and internalizing. J Clin Invest. 2007; 117:94–98.

Article20. National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002; 106:3143–3421.21. Harrison CM, Goddard JM, Rittey CD. The use of regional anaesthetic blockade in a child with recurrent erythromelalgia. Arch Dis Child. 2003; 88:65–66.

Article22. Brola W, Sobolewski P, Fudala M, Goral A, Kasprzyk M, Szczuchniak W, et al. Metabolic syndrome in Polish ischemic stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015; 24:2167–2172.

Article23. Lee JS, Chang PY, Zhang Y, Kizer JR, Best LG, Howard BV. Triglyceride and HDL-C dyslipidemia and risks of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke by glycemic dysregulation status: the strong heart study. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40:529–537.

Article24. Gu X, Li Y, Chen S, Yang X, Liu F, Li Y, et al. Association of lipids with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: a prospective cohort study among 267 500 Chinese. Stroke. 2019; 50:3376–3384.25. Cui Q, Naikoo NA. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors in ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Afr Health Sci. 2019; 19:2121–2129.

Article26. Liu X, Yan L, Xue F. The associations of lipids and lipid ratios with stroke: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019; 21:127–135.

Article27. Toth PP, Granowitz C, Hull M, Liassou D, Anderson A, Philip S. High triglycerides are associated with increased cardiovascular events, medical costs, and resource use: a real-world administrative claims analysis of statin-treated patients with high residual cardiovascular risk. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7:e008740.

Article28. Shin DW, Lee KB, Seo JY, Kim JS, Roh H, Ahn MY, et al. Association between hypertriglyceridemia and lacunar infarction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015; 24:1873–1878.

Article29. Nichols GA, Philip S, Reynolds K, Granowitz CB, Fazio S. Increased residual cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes and high versus normal triglycerides despite statin-controlled LDL cholesterol. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019; 21:366–371.

Article30. Ren Y, Ren Q, Lu J, Guo X, Huo X, Ji L, et al. Low triglyceride as a marker for increased risk of cardiovascular diseases in patients with long-term type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional survey in China. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018; 34:e2960.

Article31. Sultan S, Dowling M, Kirton A, DeVeber G, Linds A, Elkind MS, et al. Dyslipidemia in children with arterial ischemic stroke: prevalence and risk factors. Pediatr Neurol. 2018; 78:46–54.32. Lee H, Park JB, Hwang IC, Yoon YE, Park HE, Choi SY, et al. Association of four lipid components with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in statin-naïve young adults: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020; 27:870–881.

Article33. Huang YQ, Huang JY, Liu L, Chen CL, Yu YL, Tang ST, et al. Relationship between triglyceride levels and ischaemic stroke in elderly hypertensive patients. Postgrad Med J. 2020; 96:128–133.

Article34. Wang W, Shen C, Zhao H, Tang W, Yang S, Li J, et al. A prospective study of the hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype and risk of incident ischemic stroke in a Chinese rural population. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018; 138:156–162.

Article35. Saeed A, Feofanova EV, Yu B, Sun W, Virani SS, Nambi V, et al. Remnant-like particle cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein triglycerides, and incident cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:156–169.

Article36. Morrison AC, Ballantyne CM, Bray M, Chambless LE, Sharrett AR, Boerwinkle E. LPL polymorphism predicts stroke risk in men. Genet Epidemiol. 2002; 22:233–242.

Article37. Munshi A, Babu MS, Kaul S, Rajeshwar K, Balakrishna N, Jyothy A. Association of LPL gene variant and LDL, HDL, VLDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels with ischemic stroke and its subtypes. J Neurol Sci. 2012; 318:51–54.

Article38. Pi Y, Zhang L, Yang Q, Li B, Guo L, Fang C, et al. Apolipoprotein A5 gene promoter region-1131T/C polymorphism is associated with risk of ischemic stroke and elevated triglyceride levels: a meta-analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012; 33:558–565.39. Nichols GA, Philip S, Reynolds K, Granowitz CB, Fazio S. Increased cardiovascular risk in hypertriglyceridemic patients with statin-controlled LDL cholesterol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018; 103:3019–3027.

Article40. Toth PP, Philip S, Hull M, Granowitz C. Association of elevated triglycerides with increased cardiovascular risk and direct costs in statin-treated patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019; 94:1670–1680.

Article41. Wang A, Li H, Yuan J, Zuo Y, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. Visit-to-visit variability of lipids measurements and the risk of stroke and stroke types: a prospective cohort study. J Stroke. 2020; 22:119–129.

Article42. Kivioja R, Pietilä A, Martinez-Majander N, Gordin D, Havulinna AS, Salomaa V, et al. Risk factors for early-onset ischemic stroke: a case-control study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7:e009774.

Article43. Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2007; 298:309–316.

Article44. Freiberg JJ, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Jensen JS, Nordestgaard BG. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of ischemic stroke in the general population. JAMA. 2008; 300:2142–2152.

Article45. Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Schnohr P, Jensen GB, Benn M. Nonfasting triglycerides, cholesterol, and ischemic stroke in the general population. Ann Neurol. 2011; 69:628–634.

Article46. Iso H, Imano H, Yamagishi K, Ohira T, Cui R, Noda H, et al. Fasting and non-fasting triglycerides and risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease in Japanese men and women: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis. 2014; 237:361–368.

Article47. Tada H, Nomura A, Yoshimura K, Itoh H, Komuro I, Yamagishi M, et al. Fasting and non-fasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients under statin therapy. Circ J. 2020; 84:509–515.

Article48. Tziomalos K, Giampatzis V, Bouziana SD, Spanou M, Kostaki S, Papadopoulou M, et al. Prognostic significance of major lipids in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Metab Brain Dis. 2017; 32:395–400.

Article49. Dziedzic T, Slowik A, Gryz EA, Szczudlik A. Lower serum triglyceride level is associated with increased stroke severity. Stroke. 2004; 35:e151–e152.

Article50. Ryu WS, Lee SH, Kim CK, Kim BJ, Yoon BW. Effects of low serum triglyceride on stroke mortality: a prospective follow-up study. Atherosclerosis. 2010; 212:299–304.

Article51. Weir CJ, Sattar N, Walters MR, Lees KR. Low triglyceride, not low cholesterol concentration, independently predicts poor outcome following acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003; 16:76–82.

Article52. Pikija S, Milevcić D, Trkulja V, Kidemet-Piskac S, Pavlicek I, Sokol N. Higher serum triglyceride level in patients with acute ischemic stroke is associated with lower infarct volume on CT brain scans. Eur Neurol. 2006; 55:89–92.

Article53. Zhao Y, Yang C, Yan X, Ma X, Wang X, Zou C, et al. Prognosis and associated factors among elderly patients with small artery occlusion. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:15380.

Article54. Liu L, Zhan L, Wang Y, Bai C, Guo J, Lin Q, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the short-term prognosis of acute ischemic stroke: a hospital-based retrospective study. Lipids Health Dis. 2015; 14:76.

Article55. Deng QW, Wang H, Sun CZ, Xing FL, Zhang HQ, Zuo L, et al. Triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio predicts worse outcomes after acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2017; 24:283–291.

Article56. Deng QW, Li S, Wang H, Lei L, Zhang HQ, Gu ZT, et al. The short-term prognostic value of the triglyceride-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in acute ischemic stroke. Aging Dis. 2018; 9:498–506.

Article57. Kang K, Lee JJ, Park JM, Kwon O, Han SW, Kim BK. High nonfasting triglyceride concentrations predict good outcome following acute ischaemic stroke. Neurol Res. 2017; 39:779–786.

Article58. Deng Q, Li S, Zhang H, Wang H, Gu Z, Zuo L, et al. Association of serum lipids with clinical outcome in acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2019; 59:236–244.

Article59. Celap I, Nikolac Gabaj N, Demarin V, Basic Kes V, Simundic AM. Genetic and lifestyle predictors of ischemic stroke severity and outcome. Neurol Sci. 2019; 40:2565–2572.

Article60. Xu T, Zhang JT, Yang M, Zhang H, Liu WQ, Kong Y, et al. Dyslipidemia and outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Biomed Environ Sci. 2014; 27:106–110.61. Li X, Li X, Fang F, Fu X, Lin H, Gao Q. Is metabolic syndrome associated with the risk of recurrent stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017; 26:2700–2705.

Article62. Chen Y, Liu P, Qi R, Wang YH, Liu G, Wang C. Severe hypertriglyceridemia does not protect from ischemic brain injury in gene-modified hypertriglyceridemic mice. Brain Res. 2016; 1639:161–173.

Article63. Bloomfield Rubins H, Davenport J, Babikian V, Brass LM, Collins D, Wexler L, et al. Reduction in stroke with gemfibrozil in men with coronary heart disease and low HDL cholesterol: the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Circulation. 2001; 103:2828–2833.64. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380:11–22.

Article65. Smith WS, English JD, Johnston SC. Cerebrovascular diseases. In : Longo DL, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2012. p. 3270–3299.66. Boquist S, Ruotolo G, Tang R, Björkegren J, Bond MG, de Faire U, et al. Alimentary lipemia, postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, and common carotid intima-media thickness in healthy, middle-aged men. Circulation. 1999; 100:723–728.

Article67. Mori Y, Itoh Y, Komiya H, Tajima N. Association between postprandial remnant-like particle triglyceride (RLP-TG) levels and carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: assessment by meal tolerance tests (MTT). Endocrine. 2005; 28:157–163.

Article68. Boullart AC, de Graaf J, Stalenhoef AF. Serum triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012; 1821:867–875.

Article69. Nordestgaard BG, Zilversmit DB. Large lipoproteins are excluded from the arterial wall in diabetic cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Lipid Res. 1988; 29:1491–1500.

Article70. Daugherty A, Lange LG, Sobel BE, Schonfeld G. Aortic accumulation and plasma clearance of beta-VLDL and HDL: effects of diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in rabbits. J Lipid Res. 1985; 26:955–963.

Article71. Rapp JH, Lespine A, Hamilton RL, Colyvas N, Chaumeton AH, Tweedie-Hardman J, et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins isolated by selected-affinity anti-apolipoprotein B immunosorption from human atherosclerotic plaque. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994; 14:1767–1774.

Article72. Proctor SD, Mamo JC. Intimal retention of cholesterol derived from apolipoprotein B100- and apolipoprotein B48-containing lipoproteins in carotid arteries of Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003; 23:1595–1600.

Article73. Nordestgaard BG, Wootton R, Lewis B. Selective retention of VLDL, IDL, and LDL in the arterial intima of genetically hyperlipidemic rabbits in vivo: molecular size as a determinant of fractional loss from the intima-inner media. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995; 15:534–542.74. Schwartz EA, Reaven PD. Lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012; 1821:858–866.

Article75. Nakamura T, Obata JE, Takano H, Kawabata K, Sano K, Kobayashi T, et al. High serum levels of remnant lipoproteins predict ischemic stroke in patients with metabolic syndrome and mild carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2009; 202:234–240.

Article76. Wilhelm MG, Cooper AD. Induction of atherosclerosis by human chylomicron remnants: a hypothesis. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003; 10:132–139.

Article77. Hennig B, Toborek M, McClain CJ. High-energy diets, fatty acids and endothelial cell function: implications for atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001; 20(2 Suppl):97–105.

Article78. Eiselein L, Wilson DW, Lamé MW, Rutledge JC. Lipolysis products from triglyceride-rich lipoproteins increase endothelial permeability, perturb zonula occludens-1 and F-actin, and induce apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007; 292:H2745–H2753.

Article79. Wang L, Gill R, Pedersen TL, Higgins LJ, Newman JW, Rutledge JC. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipolysis releases neutral and oxidized FFAs that induce endothelial cell inflammation. J Lipid Res. 2009; 50:204–213.

Article80. Nicolson GL. Metabolic syndrome and mitochondrial function: molecular replacement and antioxidant supplements to prevent membrane peroxidation and restore mitochondrial function. J Cell Biochem. 2007; 100:1352–1369.

Article81. Lupattelli G, Lombardini R, Schillaci G, Ciuffetti G, Marchesi S, Siepi D, et al. Flow-mediated vasoactivity and circulating adhesion molecules in hypertriglyceridemia: association with small, dense LDL cholesterol particles. Am Heart J. 2000; 140:521–526.

Article82. Lundman P, Eriksson M, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Karpe F, Tornvall P. Transient triglyceridemia decreases vascular reactivity in young, healthy men without risk factors for coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1997; 96:3266–3268.

Article83. Vogel RA, Corretti MC, Plotnick GD. Effect of a single high-fat meal on endothelial function in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1997; 79:350–354.

Article84. Gudmundsson GS, Sinkey CA, Chenard CA, Stumbo PJ, Haynes WG. Resistance vessel endothelial function in healthy humans during transient postprandial hypertriglyceridemia. Am J Cardiol. 2000; 85:381–385.

Article85. Lewis TV, Dart AM, Chin-Dusting JP. Endothelium-dependent relaxation by acetylcholine is impaired in hypertriglyceridemic humans with normal levels of plasma LDL cholesterol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 33:805–812.

Article86. Yunoki K, Nakamura K, Miyoshi T, Enko K, Kubo M, Murakami M, et al. Impact of hypertriglyceridemia on endothelial dysfunction during statin ± ezetimibe therapy in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108:333–339.

Article87. Nagashima H, Endo M. Pitavastatin prevents postprandial endothelial dysfunction via reduction of the serum triglyceride level in obese male subjects. Heart Vessels. 2011; 26:428–434.

Article88. Bae JH, Bassenge E, Kim KB, Kim YN, Kim KS, Lee HJ, et al. Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia impairs endothelial function by enhanced oxidant stress. Atherosclerosis. 2001; 155:517–523.

Article89. Anderson RA, Evans ML, Ellis GR, Graham J, Morris K, Jackson SK, et al. The relationships between post-prandial lipaemia, endothelial function and oxidative stress in healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2001; 154:475–483.

Article90. Kawasaki S, Taniguchi T, Fujioka Y, Takahashi A, Takahashi T, Domoto K, et al. Chylomicron remnant induces apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000; 902:336–341.

Article91. Abe Y, El-Masri B, Kimball KT, Pownall H, Reilly CF, Osmundsen K, et al. Soluble cell adhesion molecules in hypertriglyceridemia and potential significance on monocyte adhesion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998; 18:723–731.

Article92. Benítez MB, Cuniberti L, Fornari MC, Gómez Rosso L, Berardi V, Elikir G, et al. Endothelial and leukocyte adhesion molecules in primary hypertriglyceridemia. Atherosclerosis. 2008; 197:679–687.

Article93. Kashyap SR, Belfort R, Cersosimo E, Lee S, Cusi K. Chronic low-dose lipid infusion in healthy patients induces markers of endothelial activation independent of its metabolic effects. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2008; 3:141–146.

Article94. Zernecke A, Shagdarsuren E, Weber C. Chemokines in atherosclerosis: an update. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008; 28:1897–1908.95. Maeno Y, Kashiwagi A, Nishio Y, Takahara N, Kikkawa R. IDL can stimulate atherogenic gene expression in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000; 48:127–138.

Article96. Park SY, Lee JH, Kim YK, Kim CD, Rhim BY, Lee WS, et al. Cilostazol prevents remnant lipoprotein particle-induced monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells by suppression of adhesion molecules and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression via lectin-like receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005; 312:1241–1248.

Article97. Domoto K, Taniguchi T, Takaishi H, Takahashi T, Fujioka Y, Takahashi A, et al. Chylomicron remnants induce monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression via p38 MAPK activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 2003; 171:193–200.

Article98. Gower RM, Wu H, Foster GA, Devaraj S, Jialal I, Ballantyne CM, et al. CD11c/CD18 expression is upregulated on blood monocytes during hypertriglyceridemia and enhances adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011; 31:160–166.

Article99. Kawakami A, Tanaka A, Nakajima K, Shimokado K, Yoshida M. Atorvastatin attenuates remnant lipoprotein-induced monocyte adhesion to vascular endothelium under flow conditions. Circ Res. 2002; 91:263–271.

Article100. Dichtl W, Nilsson L, Goncalves I, Ares MP, Banfi C, Calara F, et al. Very low-density lipoprotein activates nuclear factor-kappaB in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 1999; 84:1085–1094.101. Wang L, Lim EJ, Toborek M, Hennig B. The role of fatty acids and caveolin-1 in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced endothelial cell activation. Metabolism. 2008; 57:1328–1339.102. Antonios N, Angiolillo DJ, Silliman S. Hypertriglyceridemia and ischemic stroke. Eur Neurol. 2008; 60:269–278.

Article103. Scirica BM, Morrow DA. Is C-reactive protein an innocent bystander or proatherogenic culprit?: the verdict is still out. Circulation. 2006; 113:2128–2134.104. Schunkert H, Samani NJ. Elevated C-reactive protein in atherosclerosis: chicken or egg? N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1953–1955.105. Verma S, Devaraj S, Jialal I. Is C-reactive protein an innocent bystander or proatherogenic culprit?: C-reactive protein promotes atherothrombosis. Circulation. 2006; 113:2135–2150.106. Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM, Tennent GA, Gallimore JR, Kahan MC, Bellotti V, et al. Targeting C-reactive protein for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2006; 440:1217–1221.

Article107. Rosenson RS, Shott S, Tangney CC. Hypertriglyceridemia is associated with an elevated blood viscosity Rosenson: triglycerides and blood viscosity. Atherosclerosis. 2002; 161:433–439.

Article108. Késmárky G, Kenyeres P, Rábai M, Tóth K. Plasma viscosity: a forgotten variable. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2008; 39:243–246.

Article109. Zhao T, Guo J, Li H, Huang W, Xian X, Ross CJ, et al. Hemorheological abnormalities in lipoprotein lipase deficient mice with severe hypertriglyceridemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006; 341:1066–1071.

Article110. Vayá A, Hernández-Mijares A, Bonet E, Sendra R, Solá E, Pérez R, et al. Association between hemorheological alterations and metabolic syndrome. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011; 49:493–503.

Article111. Leonhardt H, Arntz HR, Klemens UH. Studies of plasma viscosity in primary hyperlipoproteinaemia. Atherosclerosis. 1977; 28:29–40.

Article112. Seplowitz AH, Chien S, Smith FR. Effects of lipoproteins on plasma viscosity. Atherosclerosis. 1981; 38:89–95.

Article113. Lee AJ, Mowbray PI, Lowe GD, Rumley A, Fowkes FG, Allan PL. Blood viscosity and elevated carotid intima-media thickness in men and women: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Circulation. 1998; 97:1467–1473.114. Lowe GD, Lee AJ, Rumley A, Price JF, Fowkes FG. Blood viscosity and risk of cardiovascular events: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Br J Haematol. 1997; 96:168–173.

Article115. Tikhomirova IA, Oslyakova AO, Mikhailova SG. Microcirculation and blood rheology in patients with cerebrovascular disorders. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011; 49:295–305.

Article116. Hu F, Alcasabas AA, Elledge SJ. Asf1 links Rad53 to control of chromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 2001; 15:1061–1066.

Article117. Furie B, Furie BC. Mechanisms of thrombus formation. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:938–949.

Article118. Simpson HC, Mann JI, Meade TW, Chakrabarti R, Stirling Y, Woolf L. Hypertriglyceridaemia and hypercoagulability. Lancet. 1983; 1:786–790.

Article119. Andersen P. Hypercoagulability and reduced fibrinolysis in hyperlipidemia: relationship to the metabolic cardiovascular syndrome. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992; 20 Suppl 8:S29–S31.

Article120. Silveira A. Postprandial triglycerides and blood coagulation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001; 109:S527–S532.

Article121. Negri M, Arigliano PL, Talamini G, Carlini S, Manzato F, Bonadonna G. Levels of plasma factor VII and factor VII activated forms as a function of plasma triglyceride levels. Atherosclerosis. 1993; 99:55–61.

Article122. Ohni M, Mishima K, Nakajima K, Yamamoto M, Hata Y. Serum triglycerides and blood coagulation factors VII and X, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1995; 2 Suppl 1:S41–S46.

Article123. Chan P, Huang TY, Shieh SM, Lin TS, Tsai CW. Thrombophilia in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1997; 4:425–429.124. Carvalho de Sousa J, Bruckert E, Giral P, Soria C, Chapman J, Truffert J, et al. Coagulation factor VII and plasma triglycerides: decreased catabolism as a possible mechanism of factor VII hyperactivity. Haemostasis. 1989; 19:125–130.125. Minnema MC, Wittekoek ME, Schoonenboom N, Kastelein JJ, Hack CE, ten Cate H. Activation of the contact system of coagulation does not contribute to the hemostatic imbalance in hypertriglyceridemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999; 19:2548–2553.

Article126. Mussoni L, Mannucci L, Sirtori M, Camera M, Maderna P, Sironi L, et al. Hypertriglyceridemia and regulation of fibrinolytic activity. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992; 12:19–27.

Article127. Hiraga T, Shimada M, Tsukada T, Murase T. Hypertriglyceridemia, but not hypercholesterolemia, is associated with the alterations of fibrinolytic system. Horm Metab Res. 1996; 28:603–606.

Article128. Byberg L, Smedman A, Vessby B, Lithell H. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and relations to fatty acid composition in the diet and in serum cholesterol esters. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001; 21:2086–2092.

Article129. Tholstrup T, Miller GJ, Bysted A, Sandström B. Effect of individual dietary fatty acids on postprandial activation of blood coagulation factor VII and fibrinolysis in healthy young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003; 77:1125–1132.

Article130. Mitropoulos KA, Miller GJ, Watts GF, Durrington PN. Lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins activates coagulant factor XII: a study in familial lipoprotein-lipase deficiency. Atherosclerosis. 1992; 95:119–125.

Article131. Stiko-Rahm A, Wiman B, Hamsten A, Nilsson J. Secretion of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells is induced by very low density lipoprotein. Arteriosclerosis. 1990; 10:1067–1073.

Article132. Kaneko T, Wada H, Wakita Y, Minamikawa K, Nakase T, Mori Y, et al. Enhanced tissue factor activity and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen in human umbilical vein endothelial cells incubated with lipoproteins. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1994; 5:385–392.133. Sironi L, Mussoni L, Prati L, Baldassarre D, Camera M, Banfi C, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 synthesis and mRNA expression in HepG2 cells are regulated by VLDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996; 16:89–96.

Article134. Morimoto S, Fujioka Y, Hosoai H, Okumura T, Masai M, Sakoda T, et al. The renin-angiotensin system is involved in the production of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 by cultured endothelial cells in response to chylomicron remnants. Hypertens Res. 2003; 26:315–323.

Article135. De Man FH, Nieuwland R, van der Laarse A, Romijn F, Smelt AH, Gevers Leuven JA, et al. Activated platelets in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia: effects of triglyceride-lowering therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2000; 152:407–414.

Article136. Jeng JR, Jeng CY, Sheu WH, Lee MM, Huang SH, Shieh SM. Gemfibrozil treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: improvement on fibrinolysis without change of insulin resistance. Am Heart J. 1997; 134:565–571.

Article137. Listenberger LL, Han X, Lewis SE, Cases S, Farese RV Jr, Ory DS, et al. Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003; 100:3077–3082.

Article138. Alberici LC, Vercesi AE, Oliveira HC. Mitochondrial energy metabolism and redox responses to hypertriglyceridemia. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2011; 43:19–23.

Article139. Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Altered lipid metabolism in brain injury and disorders. Subcell Biochem. 2008; 49:241–268.

Article140. Patel A, Barzi F, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Ueshima H, Whitlock G, et al. Serum triglycerides as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. Circulation. 2004; 110:2678–2686.

Article141. Labreuche J, Deplanque D, Touboul PJ, Bruckert E, Amarenco P. Association between change in plasma triglyceride levels and risk of stroke and carotid atherosclerosis: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2010; 212:9–15.142. Berger JS, McGinn AP, Howard BV, Kuller L, Manson JE, Otvos J, et al. Lipid and lipoprotein biomarkers and the risk of ischemic stroke in postmenopausal women. Stroke. 2012; 43:958–966.

Article143. Ridker PM. Fasting versus nonfasting triglycerides and the prediction of cardiovascular risk: do we need to revisit the oral triglyceride tolerance test? Clin Chem. 2008; 54:11–13.

Article144. Ebinger M, Heuschmann PU, Jungehuelsing GJ, Werner C, Laufs U, Endres M. The Berlin ‘Cream&Sugar’ Study: the prognostic impact of an oral triglyceride tolerance test in patients after acute ischaemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2010; 5:126–130.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Risk Factors and Biomarkers of Ischemic Stroke in Cancer Patients

- Gender Differences in Risk Factor and Clinical Outcome in Patients with Ischemic Stroke

- Relation of Stroke Risk Factors to Severity and Disability after Ischemic Stroke

- Antiplatelet Therapy for Secondary Stroke Prevention in Patients with Ischemic Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack

- Ischemic Stroke in Children: Analysis of Risk Factors