Intest Res.

2022 Jan;20(1):78-89. 10.5217/ir.2020.00124.

Effectiveness of administering zinc acetate hydrate to patients with inflammatory bowel disease and zinc deficiency: a retrospective observational two-center study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Hokkaido University Hospital, Sapporo, Japan

- 2Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, Sapporo Higashi Tokushukai Hospital, Sapporo, Japan

- 3Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Sapporo Hokushin Hospital, Sapporo, Japan

- KMID: 2525075

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5217/ir.2020.00124

Abstract

- Background/Aims

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients frequently have zinc deficiency. IBD patients with zinc deficiency have higher risks of IBD-related hospitalization, complications, and requiring surgery. This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of zinc acetate hydrate (ZAH; Nobelzin) in IBD patients with zinc deficiency.

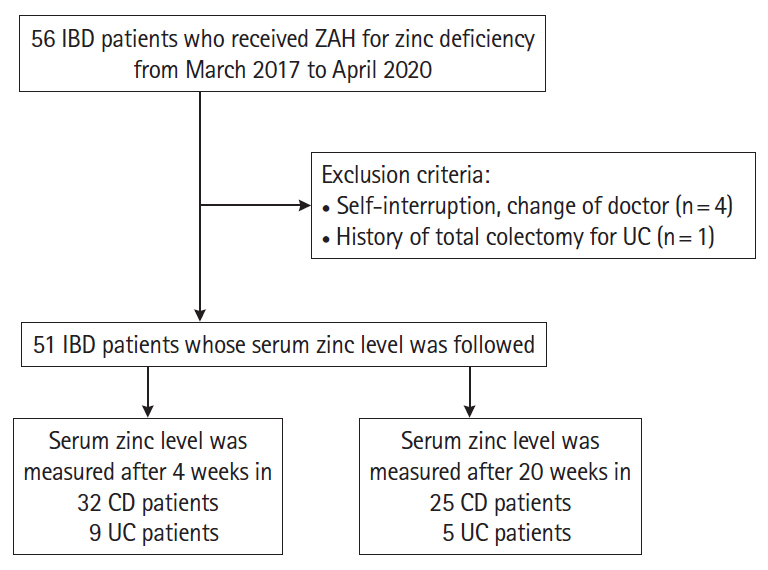

Methods

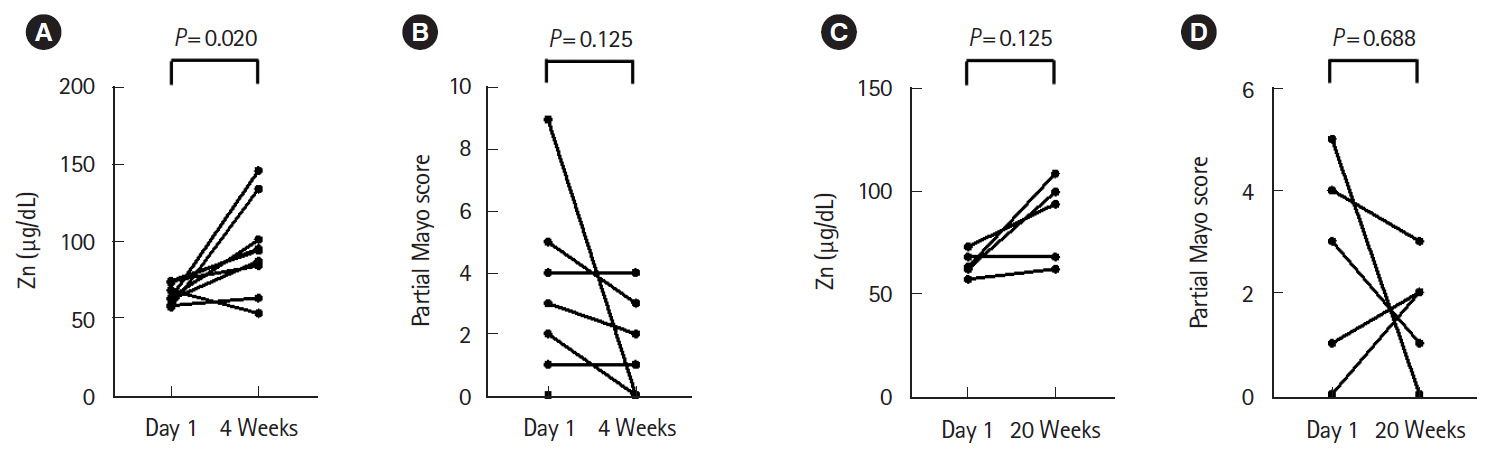

IBD patients with zinc deficiency who received ZAH from March 2017 to April 2020 were registered in this two-center, retrospective, observational study. Changes in serum zinc levels and disease activity (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI]) before and after ZAH administration were analyzed.

Results

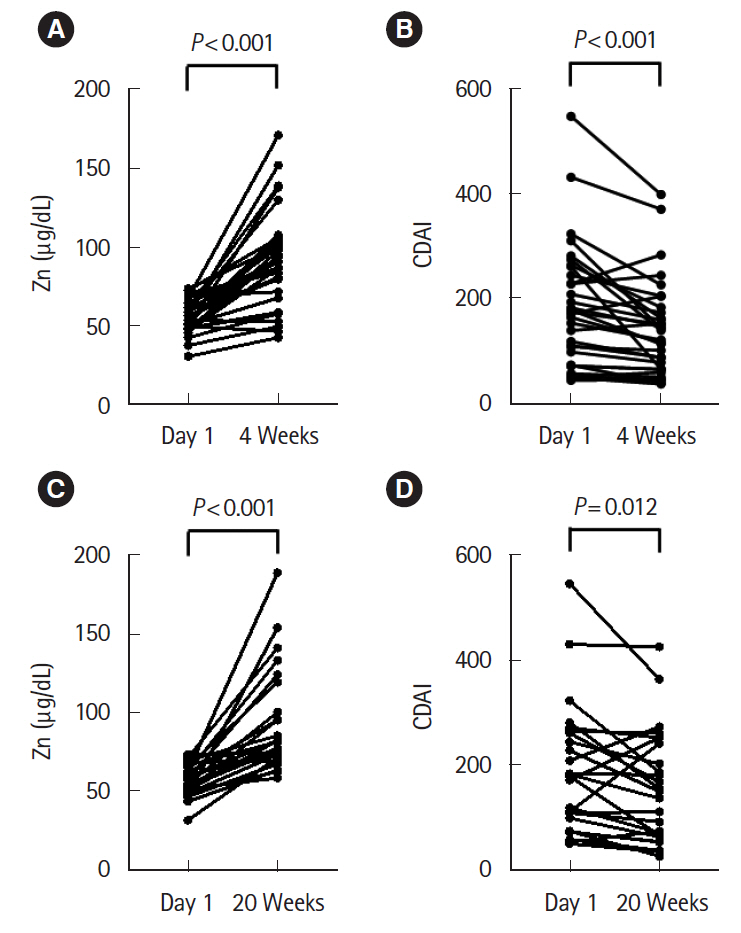

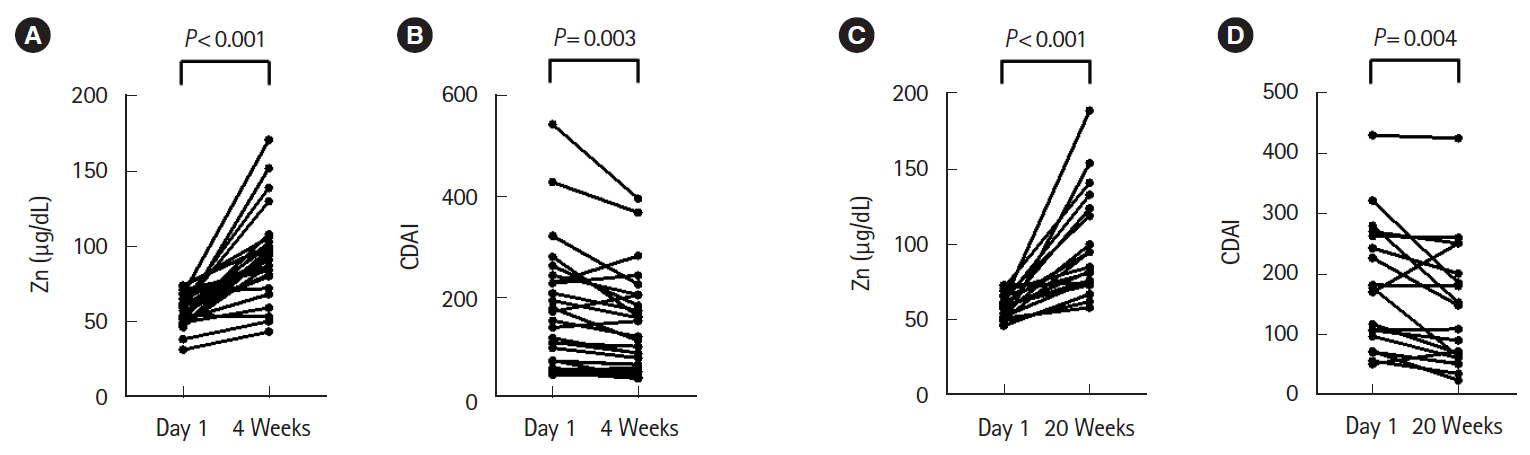

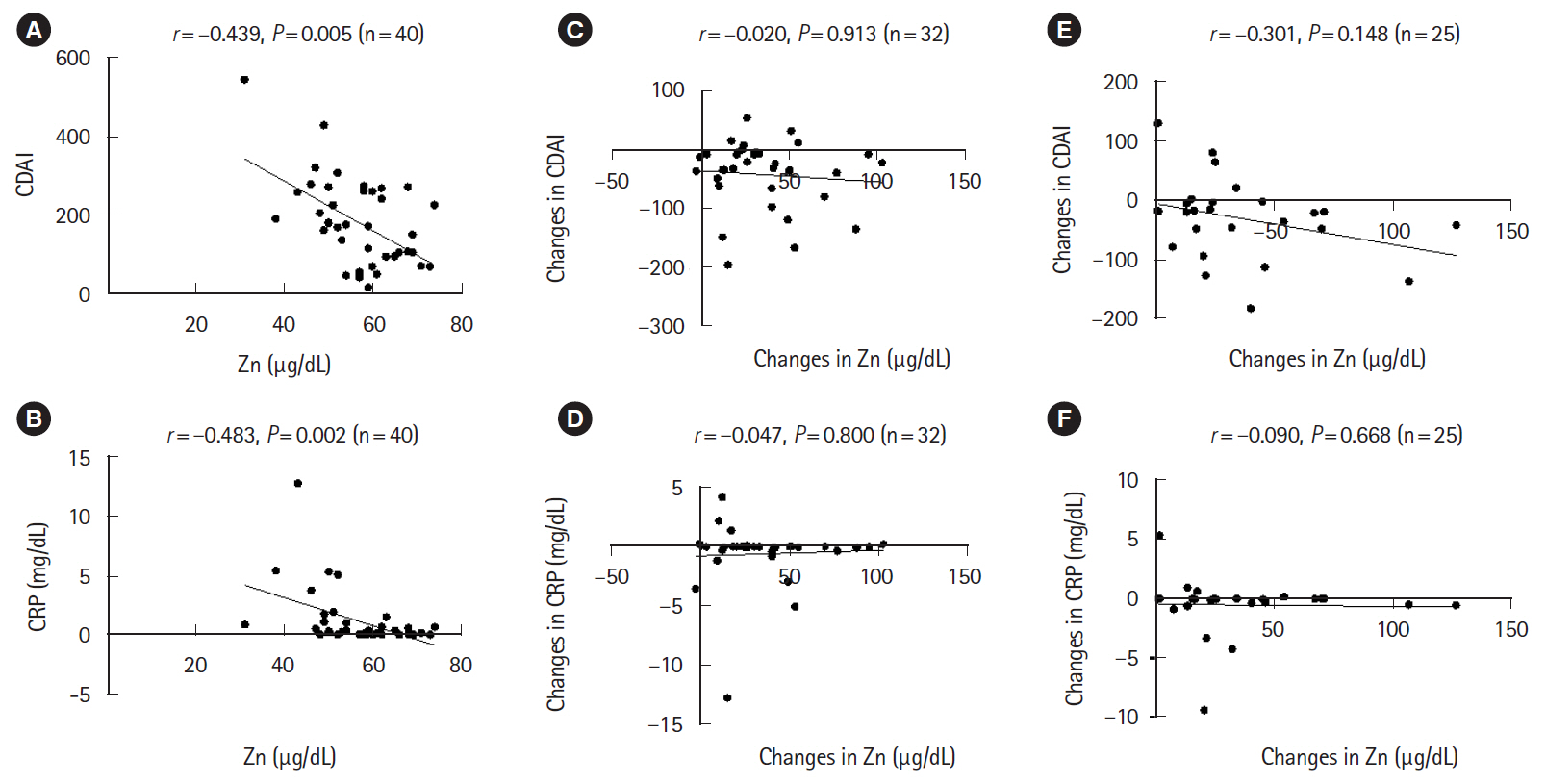

Fifty-one patients with Crohn’s disease (CD, n = 40) or ulcerative colitis (UC, n = 11) were registered. Median serum zinc level and median CDAI scores significantly improved (55.5–91.0 μg/dL, P< 0.001; 171.5–129, P< 0.001, respectively) in CD patients 4 weeks after starting ZAH administration. Similarly, median serum zinc levels and CDAI scores significantly improved (57.0–81.0 μg/dL, P< 0.001; 177–148, P= 0.012, respectively) 20 weeks after starting ZAH administration. Similar investigations were conducted in groups where no treatment change, other than ZAH administration, was implemented; significant improvements were observed in both serum zinc level and CDAI scores. Median serum zinc levels in UC patients 4 weeks after starting ZAH administration significantly improved from 63.0 to 94.0 μg/dL (P= 0.002), but no significant changes in disease activity were observed. One patient experienced side effects of abdominal discomfort and nausea.

Conclusions

ZAH administration is effective in improving zinc deficiency and may contribute to improving disease activity in IBD.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Mekhjian HS, Switz DM, Melnyk CS, Rankin GB, Brooks RK. Clinical features and natural history of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1979; 77(4 Pt 2):898–906.

Article2. Harries AD, Heatley RV. Nutritional disturbances in Crohn’s disease. Postgrad Med J. 1983; 59:690–697.

Article3. Dawson AM. Nutritional disturbances in Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1972; 59:817–819.

Article4. Dawson AM. Nutritional disturbances in Crohn’s disease. Proc R Soc Med. 1971; 64:166–170.5. Hwang C, Ross V, Mahadevan U. Micronutrient deficiencies in inflammatory bowel disease: from A to zinc. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012; 18:1961–1981.

Article6. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019; 68(Suppl 3):s1–s106.

Article7. Walsh CT, Sandstead HH, Prasad AS, Newberne PM, Fraker PJ. Zinc: health effects and research priorities for the 1990s. Environ Health Perspect. 1994; 102 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):5–46.

Article8. Filippi J, Al-Jaouni R, Wiroth JB, Hébuterne X, Schneider SM. Nutritional deficiencies in patients with Crohn’s disease in remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006; 12:185–191.

Article9. Vagianos K, Bector S, McConnell J, Bernstein CN. Nutrition assessment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007; 31:311–319.

Article10. Solomons NW, Rosenberg IH, Sandstead HH, Vo-Khactu KP. Zinc deficiency in Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 1977; 16:87–95.

Article11. Siva S, Rubin DT, Gulotta G, Wroblewski K, Pekow J. Zinc deficiency is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017; 23:152–157.

Article12. McClain C, Soutor C, Zieve L. Zinc deficiency: a complication of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1980; 78:272–279.

Article13. Sturniolo GC, Molokhia MM, Shields R, Turnberg LA. Zinc absorption in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1980; 21:387–391.

Article14. Naber TH, van den Hamer CJ, Baadenhuysen H, Jansen JB. The value of methods to determine zinc deficiency in patients with Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998; 33:514–523.

Article15. Tomita H. A proposal of the clinical standard value for diagnose of zinc deficiency by serum zinc value. Biomed Res Trace Elem. 2008; 19:22–24.16. Matsuoka K, Kobayashi T, Ueno F, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018; 53:305–353.

Article17. Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis: a randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987; 317:1625–1629.

Article18. Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976; 70:439–444.19. Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW. Rederived values of the eight coefficients of the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI). Gastroenterology. 1979; 77(4 Pt 2):843–846.

Article20. Kobayashi Y, Ohfuji S, Kondo K, et al. Association between dietary iron and zinc intake and development of ulcerative colitis: a case-control study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 34:1703–1710.

Article21. Li J, Chen H, Wang B, et al. ZnO nanoparticles act as supportive therapy in DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice by maintaining gut homeostasis and activating Nrf2 signaling. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:43126.

Article22. Itagaki M, Saruta M, Saijo H, et al. Efficacy of zinc-carnosine chelate compound, Polaprezinc, enemas in patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014; 49:164–172.

Article23. Sturniolo GC, Di Leo V, Ferronato A, D’Odorico A, D’Incà R. Zinc supplementation tightens “leaky gut” in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001; 7:94–98.

Article24. Harzer G, Kauer H. Binding of zinc to casein. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982; 35:981–987.

Article25. Fleming CR, Huizenga KA, McCall JT, Gildea J, Dennis R. Zinc nutrition in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1981; 26:865–870.

Article26. Brewer GJ. Wilson’s disease. In : Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;2005. p. 2313–2315.27. Illing AC, Shawki A, Cunningham CL, Mackenzie B. Substrate profile and metal-ion selectivity of human divalent metal-ion transporter-1. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287:30485–30496.

Article28. Kanabrocki EL, Sothern RB, Ryan MD, et al. Circadian characteristics of serum calcium, magnesium and eight trace elements and of their metallo-moieties in urine of healthy middle-aged men. Clin Ter. 2008; 159:329–346.29. McMillan EM, Rowe DJ. Clinical significance of diurnal variation in the estimation of plasma zinc. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1982; 7:629–632.

Article30. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Zinc. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press;2001. p. 442–501.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Case of Symptomatic Zinc Deficiency due to Total Parenteral Nutrition

- The Clinical Study of Zinc Deficiency Presented as a Skin Manifestation of Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

- Transient symptomatic zinc deficiency in a breast-fed, post term infant

- Acrodermatitis Enteropathica in Two Siblings: treated with zinc sulfate

- Zine Status of Adult Female in the Taegu Region as Assessed by Dietary Intake and Urinary Excretion