Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2021 Dec;27(4):307-317. 10.4069/kjwhn.2021.12.12.1.

Validation of the Korean version of the Perinatal Infant Care Social Support scale: a methodological study

- Affiliations

-

- 1College of Nursing, Chungnam National University, Daejeon, Korea

- KMID: 2524350

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2021.12.12.1

Abstract

- Purpose

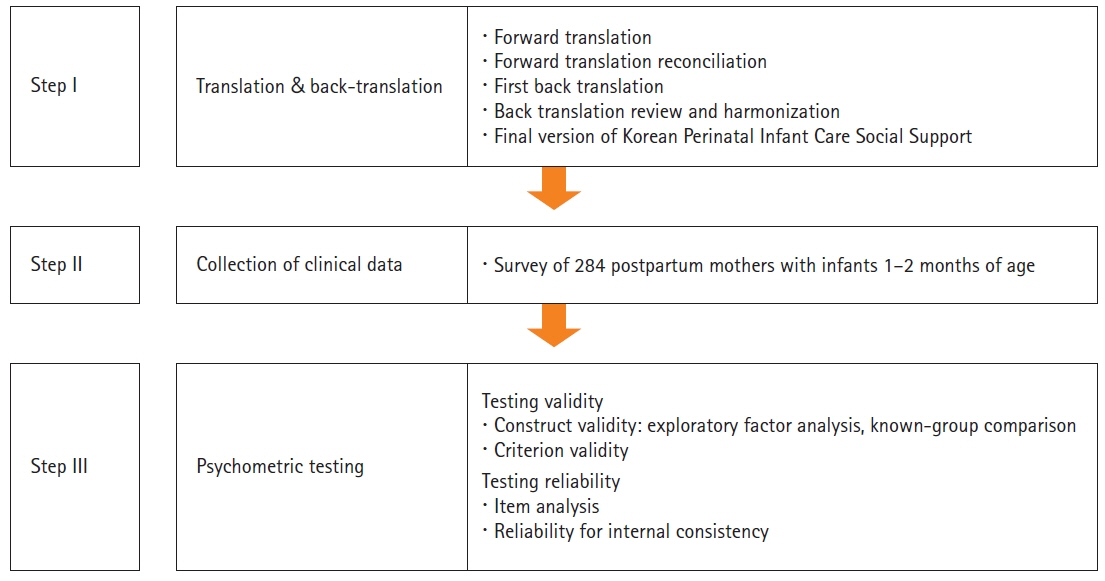

The purpose of this study was to develop and test the validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Perinatal Infant Care Social Support (K-PICSS) for postpartum mothers.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional design. The K-PICSS was developed through forward-backward translation. Online survey data were collected from 284 Korean mothers with infants 1-2 months of age. The K-PICSS consists of functional and structural domains. The functional domain of social support contains 19 items that measure the infant care practices of postpartum mothers. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and known-group comparison were used to verify the construct validity of the K-PICSS. Social support and postpartum depression were also measured to test criterion validity. Psychometric testing was not applicable to the structural social support domain.

Results

The average age of mothers was 32.76±3.34 years, and they had been married for 38.45±29.48 months. Construct validity was supported by the results of EFA, which confirmed a three-factor structure of the scale (informational support, supporting presence, and practical support). Significant correlations of the K-PICSS with social support (r=.71, p<.001) and depression (r=–.40, p<.001) were found. The K-PICSS showed reliable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values of .90 overall and .82–.83 in the three subscales. The vast majority of respondents reported that their husband or their parents were their main sources of support for infant care.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that the K-PICSS has satisfactory construct validity and reliability to measure infant care social support in Korea.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the Perinatal Infant Care Social Support tool: a methodological study

Feiyan Yi, Sukhee Ahn, Miyeon Park

Womens Health Nurs. 2024;30(2):128-139. doi: 10.4069/whn.2024.05.21.

Reference

-

References

1. Mercer RT, Walker LO. A review of nursing interventions to foster becoming a mother. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006; 35(5):568–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00080.x.

Article2. Mercer RT. Becoming a mother versus maternal role attainment. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004; 36(3):226–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04042.x.

Article3. Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G, Corcoran P. Postnatal depression in first-time mothers: prevalence and relationships between functional and structural social support at 6 and 12 weeks postpartum. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2011; 25(3):174–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2010.08.005.

Article4. Leahy-Warren P, Mulcahy H, Lehane E. The development and psychometric testing of the Perinatal Infant Care Social Support (PICSS) instrument. J Psychosom Res. 2019; 126:109813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.109813.

Article5. Castle H, Slade P, Barranco‐Wadlow M, Rogers M. Attitudes to emotional expression, social support and postnatal adjustment in new parents. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2008; 26(3):180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830701691319.

Article6. Feligreras-Alcalá D, Frías-Osuna A, Del-Pino-Casado R. Personal and family resources related to depressive and anxiety symptoms in women during puerperium. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5230. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145230.

Article7. Vaezi A, Soojoodi F, Banihashemi AT, Nojomi M. The association between social support and postpartum depression in women: a cross sectional study. Women Birth. 2019; 32(2):e238–e242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.07.014.

Article8. Zhang Y, Jin S. The impact of social support on postpartum depression: the mediator role of self-efficacy. J Health Psychol. 2016; 21(5):720–726. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314536454.

Article9. Choi H, Jung N. Factors influencing health promoting behavior in postpartum women at Sanhujoriwon. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2017; 23(2):135–144. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2017.23.2.135.

Article10. Heo SH, Noh YG. Impact of parenting stress and husband’s support on breastfeeding adaptation among breastfeeding mothers. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2017; 23(4):233–242. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2017.23.4.233.

Article11. Oh EJ, Kim HY. Factors influencing unmarried mothers’ parenting stress: based on depression, social support, and health perception. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2018; 24(2):116–125. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2018.24.2.116.

Article12. Park KY, Lee SO. A comparative study on the predictors of depression between primipara and multipara at postpartum 6 weeks. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2011; 15(1):25–36. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2011.15.1.25.

Article13. Bang KS. Infants’ temperament and health problems according to maternal postpartum depression. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2011; 41(4):444–450. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2011.41.4.444.

Article14. Kim KS, Kam S, Lee WK. The influence of self-efficacy, social support, postpartum fatigue and parenting stress on postpartum depression. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2012; 16(2):195–211. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2012.16.2.195.

Article15. Reid KM, Taylor MG. Social support, stress, and maternal postpartum depression: a comparison of supportive relationships. Soc Sci Res. 2015; 54:246–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.08.009.

Article16. Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G, Corcoran P. First-time mothers: social support, maternal parental self-efficacy and postnatal depression. J Clin Nurs. 2012; 21(3-4):388–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03701.x.

Article17. Blau PM. Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Routledge;1986. p. 372. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203792643.

Article18. Schumaker AS, Brownell A. Toward a theory of social support: closing conceptual gaps. J Soc Issues. 1984; 40(4):11–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01105.x.

Article19. Park JW. A study to development a scale of social support [dissertation]. Seoul: Yonsei University;1985. 127.20. Ha JY, Kim YJ. Factors influencing self-confidence in the maternal role among early postpartum mothers. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2013; 19(1):48–56. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2013.19.1.48.

Article21. Kim SH, Noh YG. Influence of spousal support on the relationship between acculturative stress and sense of parenting competence among married vietnamese immigrant women. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2018; 24(2):174–184. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2018.24.2.174.

Article22. Park SE, Bang KS. Correlations among working mothers’ satisfaction with non-maternal infant care, social support from others, and parenting efficacy. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2019; 23(1):23–34. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2019.23.1.23.

Article23. Negron R, Martin A, Almog M, Balbierz A, Howell EA. Social support during the postpartum period: mothers’ views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Matern Child Health J. 2013; 17(4):616–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1037-4.

Article24. Niela-Vilén H, Axelin A, Salanterä S, Melender HL. Internet-based peer support for parents: a systematic integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014; 51(11):1524–1537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.009.

Article25. McDaniel BT, Coyne SM, Holmes EK. New mothers and media use: associations between blogging, social networking, and maternal well-being. Matern Child Health J. 2012; 16(7):1509–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0918-2.

Article26. Baker B, Yang I. Social media as social support in pregnancy and the postpartum. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2018; 17:31–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2018.05.003.

Article27. Kang H. Discussions on the suitable interpretation of model fit indices and the strategies to fit model in structural equation modeling. J Korean Data Anal Soc. 2013; 15(2):653–668.28. Beavers AS, Lounsbury JW, Richards JK, Huck SW, Skolits GJ, Esquivel SL. Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in educational research. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2013; 18(6):1–8. https://doi.org/10.7275/qv2q-rk76.

Article29. World Health Organization. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments [Internet]. Geneva: Author: 2013 [cited 2020 Jun 2]. https://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/handbook_2nd_ed.pdf.30. Choi Y, Choi SH, Yun JY, Lim JA, Kwon Y, Lee HY, et al. The relationship between levels of self-esteem and the development of depression in young adults with mild depressive symptoms. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019; 98(42):e17518. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017518.

Article31. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Article32. Kim YK, Hur JW, Kim KH, Oh KS, Shin YC. Clinical application of Korean version of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2008; 47(1):36–44.33. Choi Y, Moon H. The effects of parenting stress, parenting efficacy, spouse support and social support on parenting behavior of mothers with infant children. Early Child Educ Res Rev. 2016; 20(6):407–424.34. Slomian J, Emonts P, Vigneron L, Acconcia A, Glowacz F, Reginster JY, et al. Identifying maternal needs following childbirth: a qualitative study among mothers, fathers and professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017; 17(1):213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1398-1.

Article35. Vargas-Porras C, Roa-Díaz ZM, Ferré-Grau C, De Molina-Fernández MI. Psychometric properties of the functional social support domain of perinatal infant care social support. Invest Educ Enferm. 2020; 38(2):e4. https:// doi.org/10.17533%2Fudea.iee.v38n2e04.

Article36. Kim YJ, Chung MR. A study on the change of postpartum care in Korea. Asian Cult Res. 2012; 26:217–240. https://doi.org/10.34252/acsri.2012.26..008.

Article37. Almalik MM. Understanding maternal postpartum needs: A descriptive survey of current maternal health services. J Clin Nurs. 2017; 26(23-24):4654–4663. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13812.

Article38. Shorey S, Chan SW, Chong YS, He HG. Maternal parental self-efficacy in newborn care and social support needs in Singapore: a correlational study. J Clin Nurs. 2014; 23(15-16):2272–2282. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12507.

Article39. Yu JO, June KJ, Park SH, Woo MS. Content analysis of mothers’ questions related to parenting young children in internet parenting community. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2020; 24(4):234–243. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2020.24.4.234.

Article40. Taylor ZE, Conger RD. Promoting strengths and resilience in single-mother families. Child Dev. 2017; 88(2):350–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12741.

Article41. Song JE, Ahn JA. Effect of intervention programs for improving maternal adaptation in Korea: systematic review. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2013; 19(3):129–141. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2013.19.3.129.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the Perinatal Infant Care Social Support tool: a methodological study

- Reliability and Validity Study of the Turkish Version of Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale for Healthy Behaviors

- Cognitive Function, Depression, Social Support, and Self-Care in Elderly with Hypertension

- The Influence of Self-care Agency and Social Support on Self-care Practice among Spinal Cord Injured Patients

- Development of the Developmental Support Competency Scale for Nurses Caring for Preterm Infants