J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Nov;36(46):e322. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e322.

Impact of the Coronavirus Disease Pandemic on Mental Health among Local Residents in Korea: a Cross Sectional Study

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Psychiatry, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 2Gwangmyeong City Health Center, Gwangmyeong, Korea

- KMID: 2522892

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e322

Abstract

- Background

This study aimed to evaluate traumatic stress and mental health problems associated with the prolonged coronavirus disease pandemic and to determine the differences across different age groups.

Methods

A total of 1,151 individuals who visited Gwangmyeong City Mental Health Welfare Center, South Korea, or accessed the website from September 1 to December 31, 2020, were included in the study. Mental health problems such as traumatic stress (Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-5); depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Children's Depression Inventory); anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 and Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children); suicide risk (P4 Screener); and demographic information were evaluated. The participants were divided into three groups based on age group: children and adolescents, adults, and the elderly.

Results

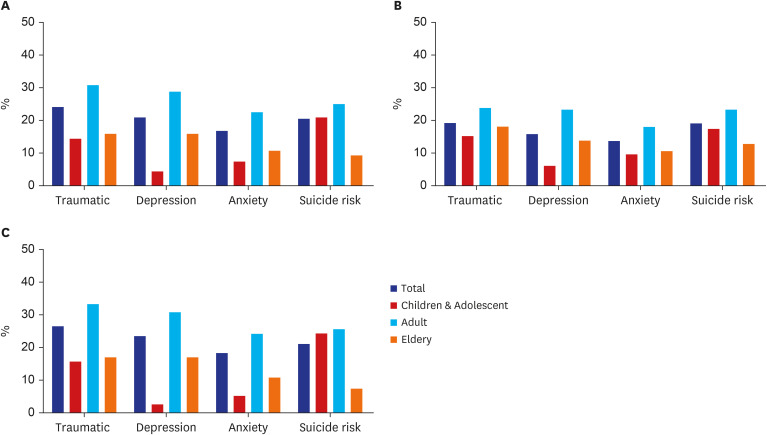

The results showed that 24.7%, 20.9%, 16.8%, and 20.5% of the participants were at high-risk for traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and suicide, respectively. The difference in the proportion of high-risk groups by age of all participants was significant for traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and suicide risk. In particular, the percentage of high-risk groups in all areas was the highest in the adult group. Also, in most areas, the ratio of the high-risk groups for children and adolescent group was the lowest, but the suicide risk-related ratio was not (adolescent group: 20.9%, adult group: 25%, elderly group 9.3%).

Conclusion

These results suggest that there is a need for continued interest in the mental health of the general population even after the initial period of coronavirus disease. Additionally, this study may be helpful when considering the resilience or risk factors of mental health in a prolonged disaster situation.

Keyword

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Gender Differences in Depression Based on National Representative Data

Hyunsuk Jeong, Hyeon Woo Yim, Seung-Yup Lee, Da Young Jung

J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(6):e36. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e36.

Reference

-

1. American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). 5th ed. Washington, D.C., USA: American Psychiatric Association;2013.2. Bridgland VM, Moeck EK, Green DM, Swain TL, Nayda DM, Matson LA, et al. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS One. 2021; 16(1):e0240146. PMID: 33428630.

Article3. González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:172–176. PMID: 32405150.

Article4. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020; 16(1):57. PMID: 32631403.

Article5. Hong J, Lee D, Ham B, Lee S, Sung S, Yoon T. The Survey of Mental Disorders in Korea. Sejong, Korea: Ministry of Health & Welfare;2017.6. O'Driscoll M, Ribeiro Dos Santos G, Wang L, Cummings DAT, Azman AS, Paireau J, et al. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021; 590(7844):140–145. PMID: 33137809.7. Chopik WJ. Death across the lifespan: age differences in death-related thoughts and anxiety. Death Stud. 2017; 41(2):69–77. PMID: 27573253.

Article8. Jung YE, Kim D, Kim WH, Roh D, Chae JH, Park JE. A brief screening tool for PTSD: validation of the Korean version of the primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (K-PC-PTSD-5). J Korean Med Sci. 2018; 33(52):e338. PMID: 30584416.

Article9. Park SJ, Choi HR, Choi JH, Kim K, Hong JP. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety Mood. 2010; 6(2):119–124.10. Cho SC, Lee YS. Development of the Korean form of the Kovacs' Children's Depression Inventory. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1990; 29(4):943–956.11. Seo JG, Park SP. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and GAD-2 in patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2015; 16(1):97. PMID: 26596588.

Article12. Kang SG, Shin JH, Song SW. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in primary school children. J Korean Med Sci. 2010; 25(8):1210–1216. PMID: 20676335.

Article13. Dube P, Kurt K, Bair MJ, Theobald D, Williams LS. The p4 screener: evaluation of a brief measure for assessing potential suicide risk in 2 randomized effectiveness trials of primary care and oncology patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010; 12(6):e1–e8.14. Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, et al. The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016; 31(10):1206–1211. PMID: 27170304.

Article15. Bovin MJ, Kimerling R, Weathers FW, Prins A, Marx BP, Post EP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of the Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) among US veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(2):e2036733. PMID: 33538826.

Article16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16(9):606–613. PMID: 11556941.17. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012; 184(3):E191–E196. PMID: 22184363.

Article18. Kovacs M. The Children's Depression, Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985; 21(4):995–998. PMID: 4089116.19. Bang YR, Park JH, Kim SH. Cut-off scores of the children's depression inventory for screening and rating severity in Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2015; 12(1):23–28.

Article20. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166(10):1092–1097. PMID: 16717171.21. Chorpita BF, Tracey SA, Brown TA, Collica TJ, Barlow DH. Assessment of worry in children and adolescents: an adaptation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1997; 35(6):569–581. PMID: 9159982.

Article22. Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, Fang SF, Jiao FY, Pettoello-Mantovani M, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr. 2020; 221:264–266.e1. PMID: 32248989.

Article23. Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, Shook N. Adolescents' motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020; 67(2):179–185. PMID: 32487491.

Article24. Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, Zhu K, Liu Q, Zhang J, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020; 174(9):898–900. PMID: 32329784.

Article25. Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. J Pediatr. 2019; 206:256–267.e3. PMID: 30322701.

Article26. Masten AS. Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001; 56(3):227–238. PMID: 11315249.

Article27. Dvorsky MR, Breaux R, Becker SP. Finding ordinary magic in extraordinary times: child and adolescent resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021; 30:1829–1831. PMID: 32613259.

Article28. Schmidt SJ, Barblan LP, Lory I, Landolt MA. Age-related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021; 12(1):1901407. PMID: 33968328.

Article29. Jung JS, Park SJ, Kim EY, Na KS, Kim YJ, Kim KG. Prediction models for high risk of suicide in Korean adolescents using machine learning techniques. PLoS One. 2019; 14(6):e0217639. PMID: 31170212.

Article30. Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 14th (2018) Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey Statistics. Seoul, Korea: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare;2018.31. American Psychological Association. Stress in America 2020: a National Mental Health Crisis. Washington, D.C., USA: American Psychiatric Association;2020.32. Birditt KS, Turkelson A, Fingerman KL, Polenick CA, Oya A. Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for psychological well-being. Gerontologist. 2021; 61(2):205–216. PMID: 33346806.

Article33. Bruine de Bruin W. Age differences in COVID-19 risk perceptions and mental health: evidence from a national US survey conducted in March 2020. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021; 76(2):e24–e29. PMID: 32470120.

Article34. Carstensen LL. Integrating cognitive and emotion paradigms to address the paradox of aging. Cogn Emotion. 2019; 33(1):119–125.

Article35. Scott SB, Poulin MJ, Silver RC. A lifespan perspective on terrorism: age differences in trajectories of response to 9/11. Dev Psychol. 2013; 49(5):986–998. PMID: 22709132.

Article36. Neubauer AB, Smyth JM, Sliwinski MJ. Age differences in proactive coping with minor hassles in daily life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019; 74(1):7–16. PMID: 29931247.

Article37. Carstensen LL. Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1995; 4(5):151–156.

Article38. Li F, Luo S, Mu W, Li Y, Ye L, Zheng X, et al. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021; 21(1):16. PMID: 33413238.

Article39. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020; 33(2):e100213. PMID: 32215365.

Article40. World Health Organization. Mental Health and Psychosocial Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2020.41. Fox S, Schwartz D. Social desirability and controllability in computerized and paper-and-pencil personality questionnaires. Comput Human Behav. 2002; 18(4):389–410.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Comparison of Changes in Health Behavior, Obesity, and Mental Health of Korean Adolescents Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Online Cross-Sectional Study

- Psychological Effects of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic

- The Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of the General Public and Children and Adolescents and Supporting Measures

- Forbearance Coping, Community Resilience, Family Resilience and Mental Health During the Post-Pandemic in China: A Moderated Mediation Model

- Coronavirus Disease 2019, School Closures, and Children’s Mental Health