J Korean Med Sci.

2021 Nov;36(45):e303. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e303.

Reliability and Quality of Korean YouTube Videos for Education Regarding Gout

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Internal Medicine, Inje University Seoul Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 2Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Myongji Hospital, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea

- 3Department of Rheumatology, Hanyang University Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2522552

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e303

Abstract

- Background

YouTube has become an increasingly popular educational tool and an important source of healthcare information. We investigated the reliability and quality of the information in Korean-language YouTube videos about gout.

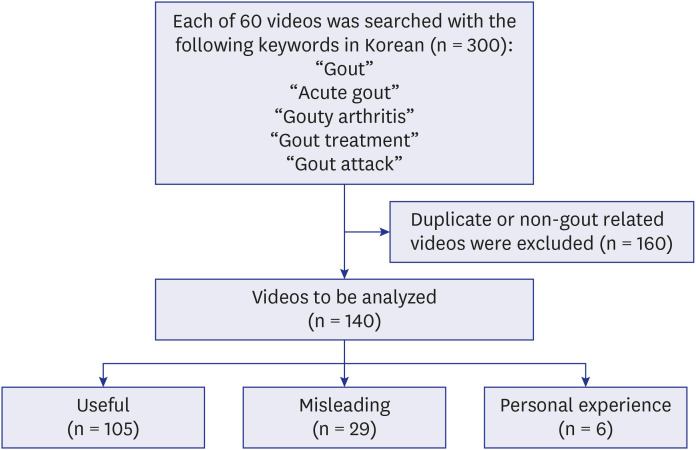

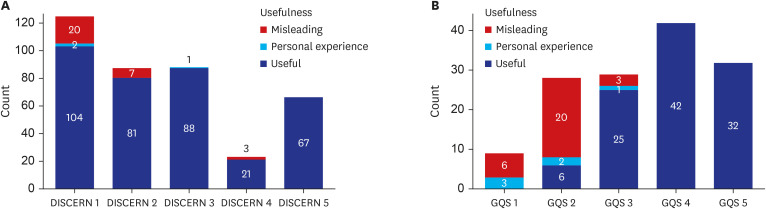

Methods

We performed a comprehensive electronic search on April 2, 2021, using the following keywords—“gout,” “acute gout,” “gouty arthritis,” “gout treatment,” and “gout attack”—and identified 140 videos in the Korean language. Two rheumatologists then categorized the videos into three groups: “useful,” “misleading,” and “personal experience.” Reliability was determined using a five-item questionnaire modified from the DISCERN validation tool, and overall quality scores were based on the Global Quality Scale (GQS).

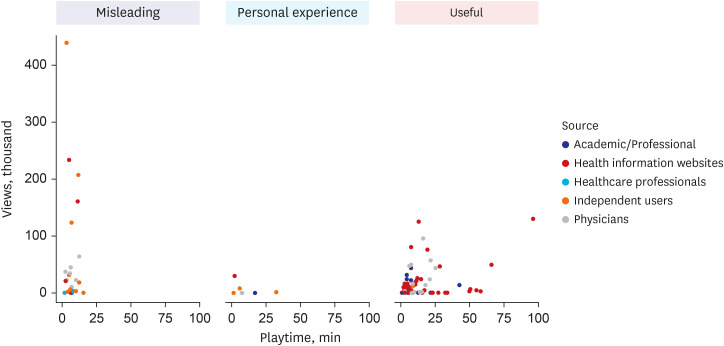

Results

Among the 140 videos identified, 105 (75.0%), 29 (20.7%), and 6 (4.3%) were categorized as “useful,” “misleading,” and “personal experience,” respectively. Most videos in the “useful” group were created by rheumatologists (70.5%). The mean DISCERN and GQS scores in the “useful” group (3.3 ± 1.0 and 3.8 ± 0.7) were higher than those in the “misleading” (0.9 ± 1.0 and 1.9 ± 0.6) and “personal experience” groups (0.8 ± 1.2 and 2.0 ± 0.8) (P < 0.001 for both the DISCERN and GQS tools).

Conclusion

Approximately 75% of YouTube videos that contain educational material regarding gout were useful; however, we observed some inaccuracies in the medical information provided. Healthcare professionals should closely monitor media content and actively participate in the development of videos that provide accurate medical information.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Dehlin M, Jacobsson L, Roddy E. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020; 16(7):380–390. PMID: 32541923.

Article2. Kim K, Go S, Son HE, Ryu JY, Lee H, Heo NJ, et al. Association between serum uric acid level and ESRD or death in a Korean population. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(28):e254. PMID: 32686371.

Article3. Gwag HB, Yang JH, Park TK, Song YB, Hahn JY, Choi JH, et al. Uric acid level has a u-shaped association with clinical outcomes in patients with vasospastic angina. J Korean Med Sci. 2017; 32(8):1275–1280. PMID: 28665063.

Article4. Kim JW, Kwak SG, Lee H, Kim SK, Choe JY, Park SH. Prevalence and incidence of gout in Korea: data from the national health claims database 2007–2015. Rheumatol Int. 2017; 37(9):1499–1506. PMID: 28676911.

Article5. Liu R, Han C, Wu D, Xia X, Gu J, Guan H, et al. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and gout in Mainland China from 2000 to 2014: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Res Int. 2015; 2015:762820. PMID: 26640795.

Article6. FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, Brignardello-Petersen R, Guyatt G, Abeles AM, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020; 72(6):744–760. PMID: 32391934.

Article7. Fox S. Online Health Search 2006. Washington, D.C., USA: Pew Research Center;2006.8. Fox S, Jones S. The Social Life of Health Information. Washington, D.C., USA: Pew Research Center;2009.9. Fox S, Purcell K. Chronic Disease and the Internet. Washington, D.C., USA: Pew Research Center;2010.10. Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Informatics J. 2015; 21(3):173–194. PMID: 24670899.

Article11. Morahan-Martin JM. How internet users find, evaluate, and use online health information: a cross-cultural review. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004; 7(5):497–510. PMID: 15667044.

Article12. IGAWorks. The Whole of Korea Has Fallen into YouTube! Seoul, Korea: IGAWorks;2020.13. Onder ME, Zengin O. YouTube as a source of information on gout: a quality analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2021; 41(7):1321–1328. PMID: 33646342.

Article14. iProspect. iProspect Search Engine User Behavior Study. Boston, MA, USA: iProspect;2006.15. Singh AG, Singh S, Singh PP. YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis--a wakeup call? J Rheumatol. 2012; 39(5):899–903. PMID: 22467934.16. Dutta A, Beriwal N, Van Breugel LM, Sachdeva S, Barman B, Saikia H, et al. YouTube as a source of medical and epidemiological information during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study of content across six languages around the globe. Cureus. 2020; 12(6):e8622. PMID: 32685293.

Article17. Delli K, Livas C, Vissink A, Spijkervet FK. Is YouTube useful as a source of information for Sjögren's syndrome? Oral Dis. 2016; 22(3):196–201. PMID: 26602325.

Article18. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999; 53(2):105–111. PMID: 10396471.

Article19. Doherty M, Jansen TL, Nuki G, Pascual E, Perez-Ruiz F, Punzi L, et al. Gout: why is this curable disease so seldom cured? Ann Rheum Dis. 2012; 71(11):1765–1770. PMID: 22863577.

Article20. Abhishek A, Doherty M. Education and non-pharmacological approaches for gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018; 57(suppl_1):i51–i58. PMID: 29272507.

Article21. Spencer K, Carr A, Doherty M. Patient and provider barriers to effective management of gout in general practice: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012; 71(9):1490–1495. PMID: 22440822.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Evaluation of the reliability and information quality of YouTube videos on implant overdenture

- Evaluation of YouTube Videos about Isotretinoin as Treatment of Acne Vulgaris

- Evaluation of YouTube Videos Regarding Clean Intermittent Catheterization Application

- YouTube as a source of information about rubber dam: quality and content analysis

- Utility Evaluation of Information from YouTube on Breastfeeding for Preterm Babies