Clinical Features and Predictors of Dysplasia in Proximal Sessile Serrated Lesions

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Changi General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

- 2Department of Pathology, Changi General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 4Pathology Academic Clinical Programme, SingHealth Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore

- KMID: 2518862

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2020.198

Abstract

- Background/Aims

Proximal colorectal cancers (CRCs) account for up to half of CRCs. Sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) are precursors to CRC. Proximal location and presence of dysplasia in SSLs predict higher risks of progression to cancer. The prevalence of dysplasia in proximal SSLs (pSSLs) and clinical characteristics of dysplastic pSSLs are not well studied.

Methods

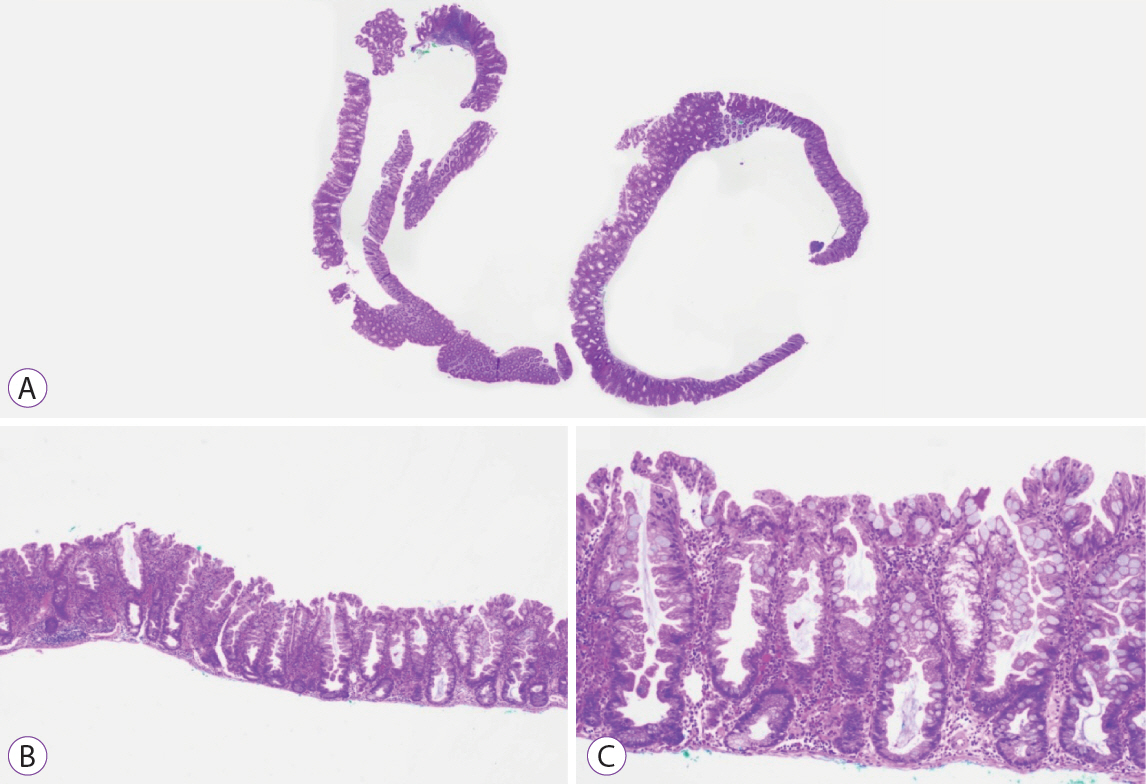

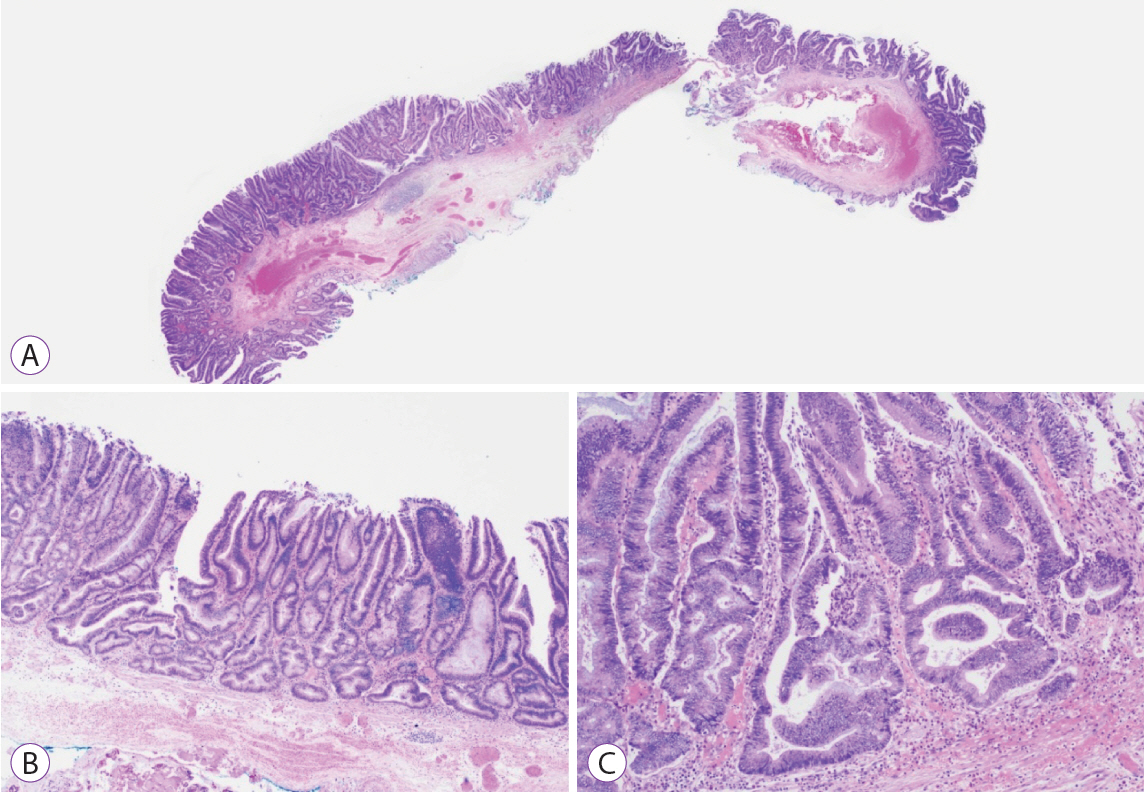

Endoscopically resected colonic polyps at our center between January 2016 and December 2017 were screened for pSSLs. Data of patients with at least one pSSL were retrieved and clinicopathological features of pSSLs were analysed. pSSLs with and without dysplasia were compared for associations.

Results

Ninety pSSLs were identified, 45 of which had dysplasia giving a prevalence of 50.0%. Older age (65.9 years vs. 60.1 years, p=0.034) was associated with the presence of dysplasia. Twelve pSSLs were 10 mm or larger. After adjusting for age, pSSLs ≥10 mm had an adjusted odds ratio of 5.98 (95% confidence interval, 1.21–29.6) of having dysplasia compared with smaller pSSLs.

Conclusions

In our cohort of pSSLs, the prevalence of dysplasia is high at 50.0% and is associated with lesion size ≥10 mm. Endoscopic resection for all proximal serrated lesions should be en-bloc to facilitate accurate histopathological examination for dysplasia as its presence warrants shorter surveillance intervals.

Keyword

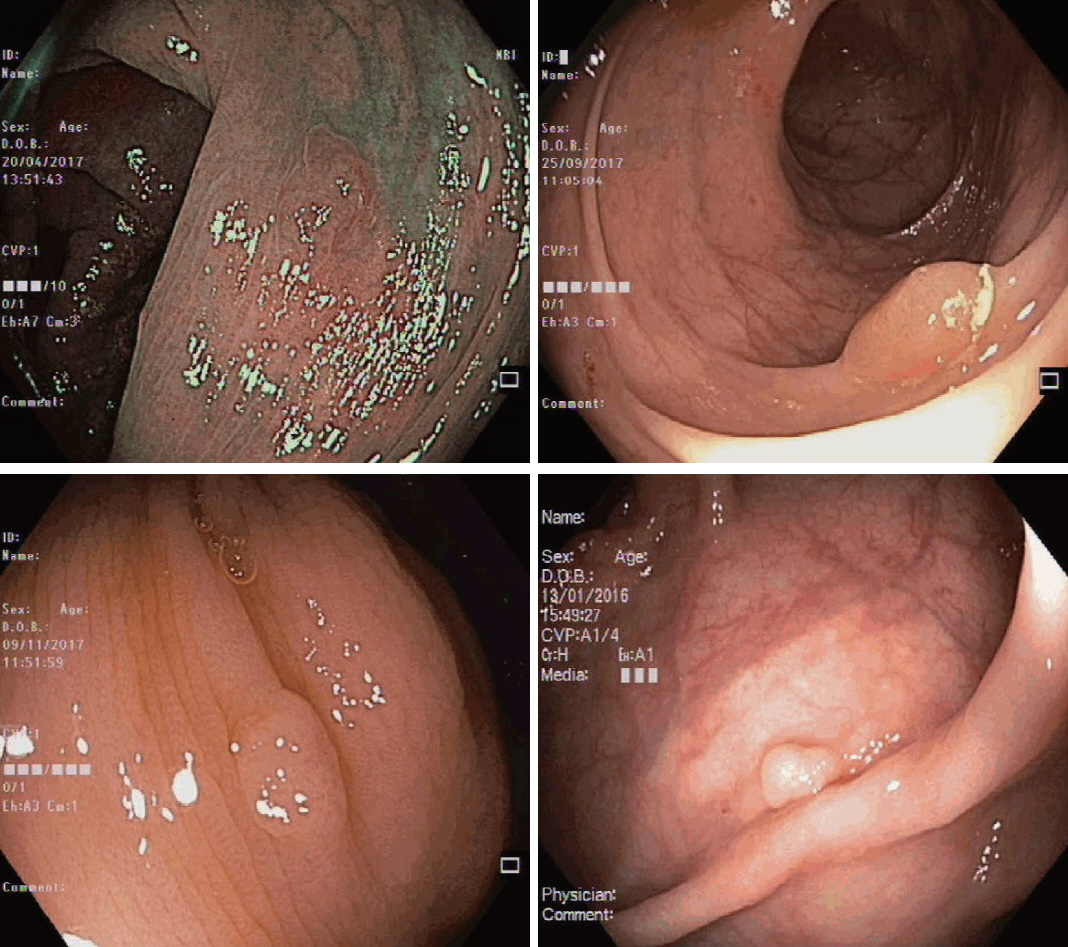

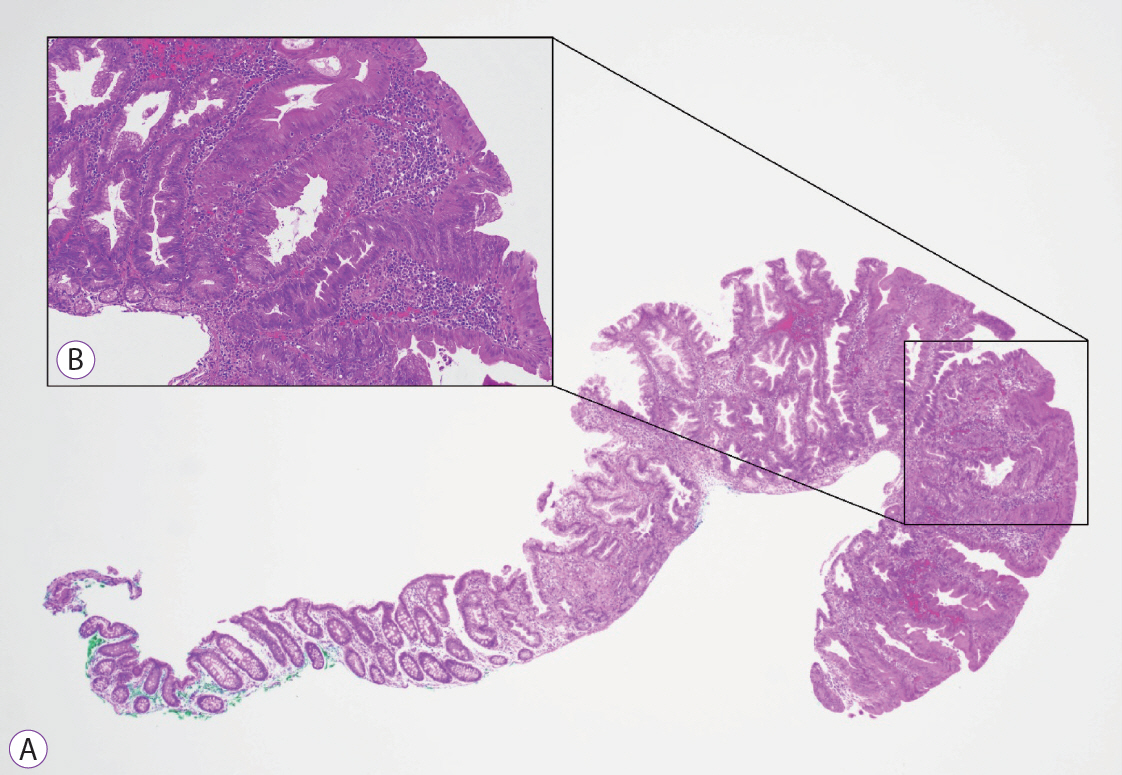

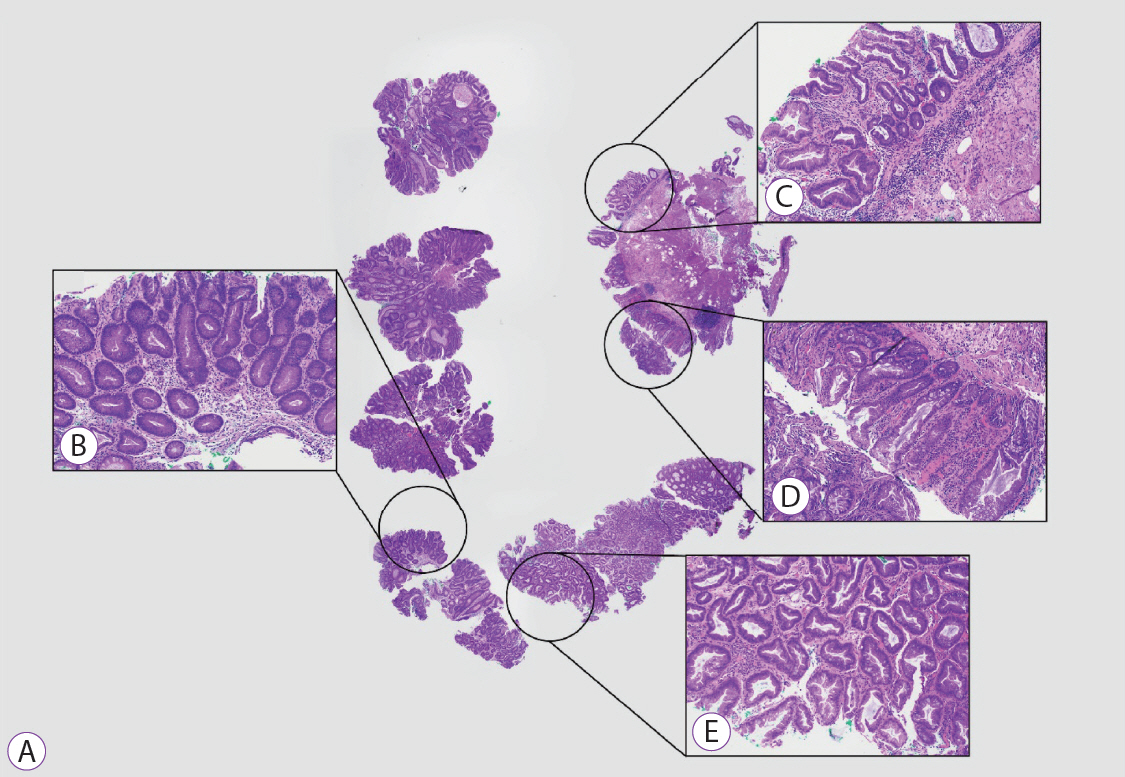

Figure

Cited by 2 articles

-

Korean guidelines for postpolypectomy colonoscopic surveillance: 2022 revised edition

Su Young Kim, Min Seob Kwak, Soon Man Yoon, Yunho Jung, Jong Wook Kim, Sun-Jin Boo, Eun Hye Oh, Seong Ran Jeon, Seung-Joo Nam, Seon-Young Park, Soo-Kyung Park, Jaeyoung Chun, Dong Hoon Baek, Mi-Young Choi, Suyeon Park, Jeong-Sik Byeon, Hyung Kil Kim, Joo Young Cho, Moon Sung Lee, Oh Young Lee

Clin Endosc. 2022;55(6):703-725. doi: 10.5946/ce.2022.136.Korean Guidelines for Postpolypectomy Colonoscopic Surveillance: 2022 revised edition

Su Young Kim, Min Seob Kwak, Soon Man Yoon, Yunho Jung, Jong Wook Kim, Sun-Jin Boo, Eun Hye Oh, Seong Ran Jeon, Seung-Joo Nam, Seon-Young Park, Soo-Kyung Park, Jaeyoung Chun, Dong Hoon Baek, Mi-Young Choi, Suyeon Park, Jeong-Sik Byeon, Hyung Kil Kim, Joo Young Cho, Moon Sung Lee, Oh Young Lee

Intest Res. 2023;21(1):20-42. doi: 10.5217/ir.2022.00096.

Reference

-

1. Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975; 36:2251–2270.

Article2. Boparai KS, Dekker E, Polak MM, Musler AR, van Eeden S, van Noesel CJ. A serrated colorectal cancer pathway predominates over the classic WNT pathway in patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2011; 178:2700–2707.

Article3. Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010; 138:2088–2100.

Article4. Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology. 2007; 50:113–130.

Article5. Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, Brown I, Leggett B, Whitehall V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013; 62:367–386.

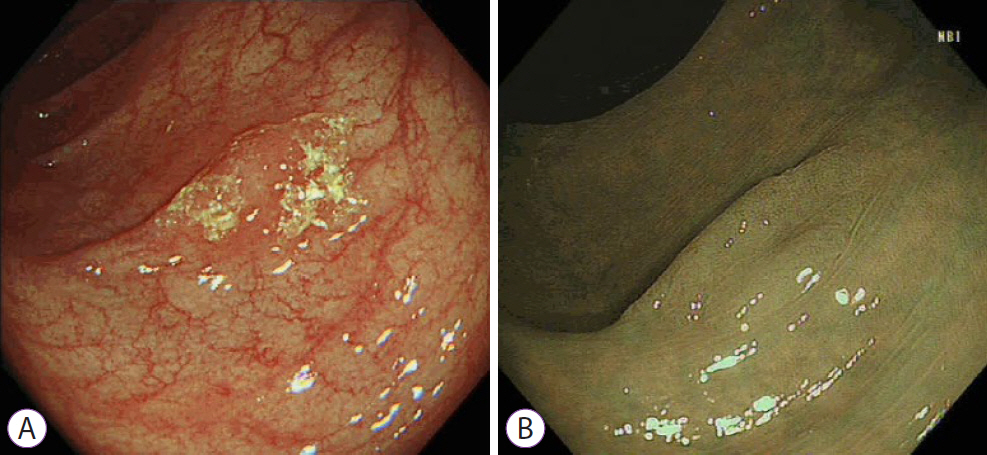

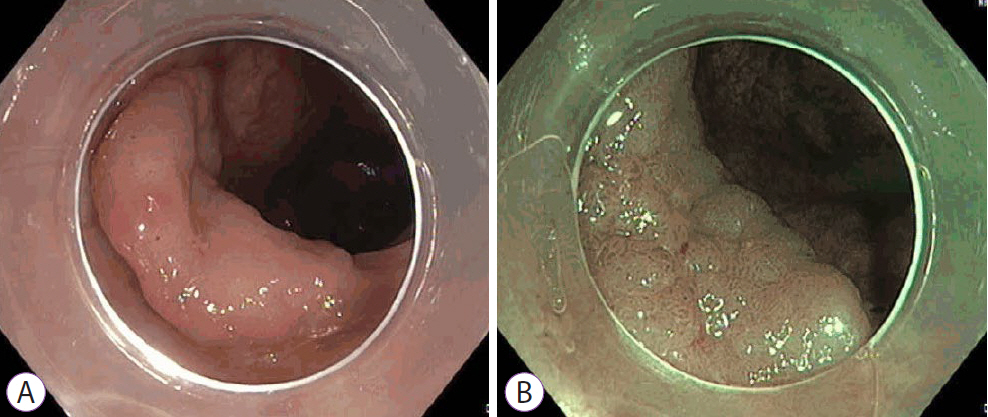

Article6. Gomez D, Dalal Z, Raw E, Roberts C, Lyndon PJ. Anatomical distribution of colorectal cancer over a 10 year period in a district general hospital: is there a true “rightward shift”? Postgrad Med J. 2004; 80:667–669.

Article7. Baber J, Anusionwu C, Nanavaty N, Agrawal S. Anatomical distribution of colorectal cancer in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. South Med J. 2014; 107:443–447.

Article8. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020; 70:7–30.

Article9. Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2019; 394:1467–1480.

Article10. Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D’Ario G, et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Ann Oncol. 2014; 25:1995–2001.

Article11. Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 16:713–732.

Article12. Anderson JC. Pathogenesis and management of serrated polyps: current status and future directions. Gut Liver. 2014; 8:582–589.

Article13. Kahi CJ, Hewett DG, Norton DL, Eckert GJ, Rex DK. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 9:42–46.

Article14. JE IJ, de Wit K, van der Vlugt M, Bastiaansen BA, Fockens P, Dekker E. Prevalence, distribution and risk of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps at a center with a high adenoma detection rate and experienced pathologists. Endoscopy. 2016; 48:740–746.

Article15. Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, et al. Increased risk of colorectal cancer development among patients with serrated polyps. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150:895–902.e5.

Article16. Bettington M, Walker N, Rosty C, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia or carcinoma. Gut. 2017; 66:97–106.

Article17. Holme Ø, Bretthauer M, Eide TJ, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with serrated polyps. Gut. 2015; 64:929–936.

Article18. IJspeert JEG, Bevan R, Senore C, et al. Detection rate of serrated polyps and serrated polyposis syndrome in colorectal cancer screening cohorts: a European overview. Gut. 2017; 66:1225–1232.

Article19. Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011; 42:1–10.

Article20. Burgess NG, Tutticci NJ, Pellise M, Bourke MJ. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with cytologic dysplasia: a triple threat for interval cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 80:307–310.

Article21. Liu C, Walker NI, Leggett BA, Whitehall VL, Bettington ML, Rosty C. Sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia: morphological patterns and correlations with MLH1 immunohistochemistry. Mod Pathol. 2017; 30:1728–1738.

Article22. Yang JF, Tang SJ, Lash RH, Wu R, Yang Q. Anatomic distribution of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without cytologic dysplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015; 139:388–393.

Article23. Abdeljawad K, Vemulapalli KC, Kahi CJ, Cummings OW, Snover DC, Rex DK. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81:517–524.

Article24. Bouwens MW, van Herwaarden YJ, Winkens B, et al. Endoscopic characterization of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with and without dysplasia. Endoscopy. 2014; 46:225–235.

Article25. Hazewinkel Y, de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, et al. Prevalence of serrated polyps and association with synchronous advanced neoplasia in screening colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014; 46:219–224.

Article26. Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2010; 63:681–686.

Article27. Sheridan TB, Fenton H, Lewin MR, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas with low- and high-grade dysplasia and early carcinomas: an immunohistochemical study of serrated lesions “caught in the act”. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006; 126:564–571.28. Armaghany T, Wilson JD, Chu Q, Mills G. Genetic alterations in colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2012; 5:19–27.29. Pan J, Xin L, Ma YF, Hu LH, Li ZS. Colonoscopy reduces colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in patients with non-malignant findings: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016; 111:355–365.

Article30. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1095–1105.

Article31. JE IJ, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia-role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 12:401–409.

Article32. Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Weiss JE, Robinson CM. Providing data for serrated polyp detection rate benchmarks: an analysis of the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017; 85:1188–1194.

Article33. Sarvepalli S, Garber A, Rothberg MB, et al. Association of adenoma and proximal sessile serrated polyp detection rates with endoscopist characteristics. JAMA Surg. 2019; 154:627–635.

Article34. Murakami T, Sakamoto N, Ritsuno H, et al. Distinct endoscopic characteristics of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with and without dysplasia/carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017; 85:590–600.

Article35. Sano W, Fujimori T, Ichikawa K, et al. Clinical and endoscopic evaluations of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with cytological dysplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018; 33:1454–1460.

Article36. Rustagi T, Rangasamy P, Myers M, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas in the proximal colon are likely to be flat, large and occur in smokers. World J Gastroenterol. 2013; 19:5271–5277.

Article37. WHO classification of tumours. Digestive System Tumours. 5th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer;2019. Chapter: Colorectal serrated lesions and polyps. p. 165–167.38. Bufill JA. Colorectal cancer: evidence for distinct genetic categories based on proximal or distal tumor location. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 113:779–788.

Article39. Rutter MD, East J, Rees CJ, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland/Public Health England post-polypectomy and post-colorectal cancer resection surveillance guidelines. Gut. 2020; 69:201–223.

Article40. Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020; 91:463–485.e5.

Article41. Kim KH, Kim KO, Jung Y, et al. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with dysplasia/adenocarcinoma in a Korean population: a Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases (KASID) multicenter study. Sci Rep. 2019; 9:3946.

Article42. Burgess NG, Pellise M, Nanda KS, et al. Clinical and endoscopic predictors of cytological dysplasia or cancer in a prospective multicentre study of large sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016; 65:437–446.

Article43. Yan HHN, Lai JCW, Ho SL, et al. RNF43 germline and somatic mutation in serrated neoplasia pathway and its association with BRAF mutation. Gut. 2017; 66:1645–1656.

Article44. Nguyen LH, Goel A, Chung DC. Pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:291–302.

Article45. He X, Hang D, Wu K, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after removal of conventional adenomas and serrated polyps. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:852–861.e4.

Article46. Kaltenbach T, Anderson JC, Burke CA, et al. Endoscopic removal of colorectal lesions-recommendations by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2020; 158:1095–1129.

Article47. Davenport JR, Su T, Zhao Z, et al. Modifiable lifestyle factors associated with risk of sessile serrated polyps, conventional adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Gut. 2018; 67:456–465.

Article48. Ng SC, Ching JY, Chan VC, et al. Association between serrated polyps and the risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk individuals. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 41:108–115.

Article49. Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009; 124:2406–2415.

Article50. Carr PR, Alwers E, Bienert S, et al. Lifestyle factors and risk of sporadic colorectal cancer by microsatellite instability status: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Ann Oncol. 2018; 29:825–834.

Article51. Limsui D, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk by molecularly defined subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010; 102:1012–1022.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Sessile Serrated Adenoma with High-grade Dysplasia

- Evolving pathologic concepts of serrated lesions of the colorectum

- Sessile Serrated Adenomas: How to Detect, Characterize and Resect

- Serrated neoplasia pathway as an alternative route of colorectal cancer carcinogenesis

- Characteristics and outcomes of endoscopically resected colorectal cancers that arose from sessile serrated adenomas and traditional serrated adenomas