Korean J Women Health Nurs.

2021 Jun;27(2):104-112. 10.4069/kjwhn.2021.05.14.

Does family support mediate the effect of anxiety and depression on maternal-fetal attachment in high-risk pregnant women admitted to the maternal-fetal intensive care unit?

- Affiliations

-

- 1Graduate School, Inje University, Busan, Korea

- 2College of Nursing and Institute of Health Science, Inje University, Busan, Korea

- KMID: 2517568

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2021.05.14

Abstract

- Purpose

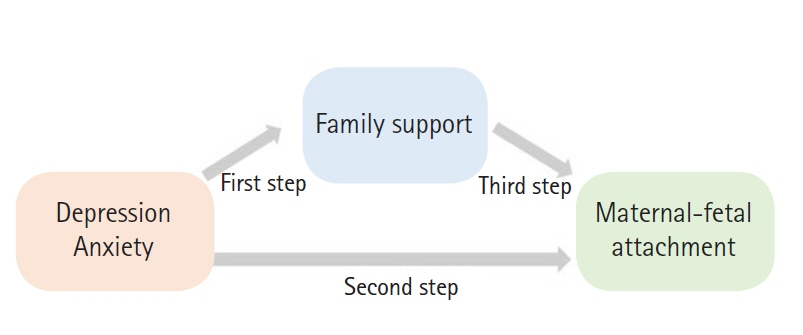

This study investigated the mediating effect of family support in the relationships of anxiety and depression with maternal-fetal attachment among pregnant women admitted to the maternal-fetal intensive care unit (MFICU) in Korea.

Methods

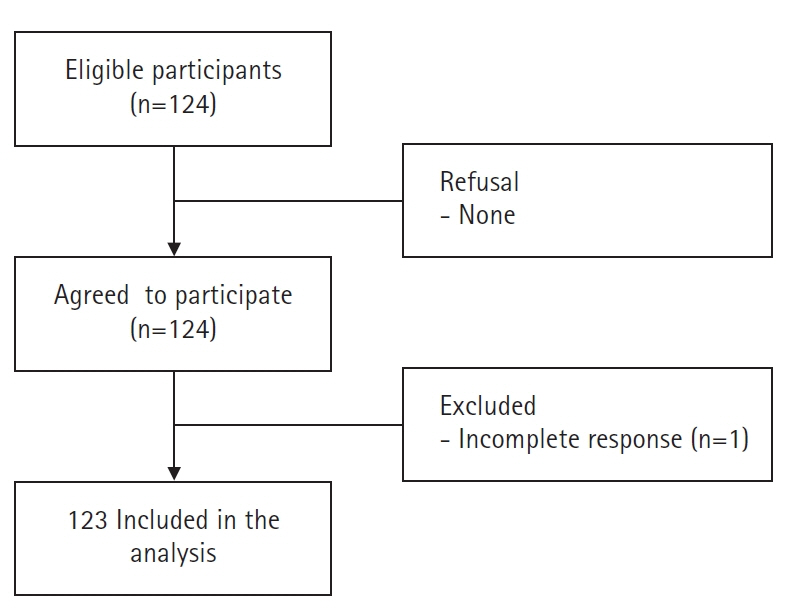

The participants were high-risk pregnant women with a gestational age of at least 20 weeks who were admitted to MFICUs in Busan and Yangsan. The Korean versions of four measurement tools were used for the self-report questionnaire: Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Cobb’s family support measurement, and Cranley’s maternal-fetal attachment scale. Data were collected from June 22 to September 20, 2020. Out of 124 participants, data from 123 respondents were analyzed. Descriptive statistics and regression analysis were done.

Results

The average age of participants was 34.1 years. Their anxiety level was medium (43.57±11.65 points out of 80) and 53.6% were identified as having moderate depression (average 10.13±5.48 points out of 30). Family support was somewhat high (average 43.30±5.03 points out of 55). The average score of maternal-fetal attachment was also somewhat high (73.37±12.14 points out of 96). Family support had a partial mediating effect in the relationships of anxiety and depression with maternal-fetal attachment among high-risk pregnant women admitted to the MFICU.

Conclusion

Maintaining family support is challenging due to the nature of the MFICU. Considering the mediating effect of family support, establishing an intervention plan to strengthen family support can be helpful as a way to improve maternal-fetal attachment for high-risk pregnant women admitted to the MFICU.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Statistics of national diseases of interest [Internet]. Seoul: Author;2020. [cited 2020 Sep 1]. Available from: http://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olapMfrnIntrsIlnsInfo.do.2. Lee EY. Influence of anxiety and dyadic adjustment on maternal-fetal attachment in high-risk pregnant women [master’s thesis]. Daegu: Kyungpook National University;2015. 42.3. Lee SY, Im JY. Measures for improving population qualifications in response to low birth and aging: birth status and policy tasks of elderly pregnant women. Seoul: Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs;2013. p. 208.4. Kim S, Cha C. Bed rest experience among high-risk primigravida. J Qual Res. 2018; 19(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.22284/qr.2018.19.1.1.

Article5. Kim HY, Moon CS. Integrated care center for high risk pregnancy and neonate: an analysis of process and problems in obstetrics. Korean J Perinatol. 2014; 25(3):140–152. https://doi.org/10.14734/kjp.2014.25.3.140.

Article6. Cranley MS. Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nurs Res. 1981; 30(5):281–284.

Article7. Kang SK, Chung MR. The relationship between pregnant woman’s stress, temperament and maternal-fetal attachment. Korean J Human Ecol. 2012; 21(2):213–223. https://doi.org/10.5934/kjhe.2012.21.2.213.

Article8. American Pregnancy Association. Depression in pregnancy [Internet]. Irving (TX): Author;c2021. [cited 2021 May 20]. Available from: http://americanpregnancy.org/pregnancyhealth/depressionduringpregnancy.html.9. Wi H, Park SY. The relationships between anxiety, depression, prenatal stress, maternal-fetal attachment and gratitude. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2012; 16(2):274–286. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2012.16.2.274.

Article10. Ko SY, Bae JG, Jung SW. A comparative study on the anxiety, depression, and maternal-fetal attachment of high-risk pregnant women and normal pregnant women. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2019; 25(2):117–126. https://doi.org/10.22802/jksbtp.2019.25.2.117.

Article11. Yu M, Kim MO. The contribution of maternal-fetal attachment: taegyo, maternal fatigue and social support during pregnancy. Child Health Nurs Res. 2014; 20(4):247–254. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2014.20.4.247.

Article12. Kim BK, Sung MH. Impact of anxiety, social support, and taegyo practice on maternal-fetal attachment in pregnant women having an abortion. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2019; 25(2):182–193. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2019.25.2.182.

Article13. Kim KY. Effects on maternal-infant attachment by the taegyo perspective prenatal class [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University;2000. 63.14. Cobb S. Presidential Address-1976. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976; 38(5):300–314. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003.

Article15. Kang HS. Experimental study of the effects of reinforcement education for rehabilitation on hemiplegia patients’ self-care activities [dissertation]. Seoul: Yonsei University;1984. 125.16. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch R, Lushene RE. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologist Press;1970. p. 24.17. Kim JT, Shin DK. A study based on the standardization of the STAI for Korea. New Med J. 1978; 21(11):69–75.18. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150:782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782.

Article19. Cox JL, Chapman G, Murray D, Jones P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord. 1996; 39(3):185–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0.

Article20. Han KW, Kim MJ, Park JM. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale, Korean version: reliability and validity. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2004; 10(2):201–207.21. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986; 51(6):1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Article22. Hong HJ, Kim SJ. The effects of positive psychology group counseling program on depression, hope and optimism of adolescent. J Korean Data Anal Soc. 2014; 16(2):1045–1059.23. Lee EJ, Park JS. Status of antepartum depression and its influencing factors in pregnant women. J Korea Acad-Industr Coop Soc. 2013; 14(8):3897–3906. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2013.14.8.3897.

Article24. Lee SH, Kim JA, Kim MK. The effect of family support on health-related quality of life in pregnant women: the moderating effect of depression. AJMAHS. 2018; 8(1):637–647. https://doi.org/10.35873/ajmahs.2018.8.1.063.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A Comparative Study on the Anxiety, Depression, and Maternal-Fetal Attachment of High-Risk Pregnant Women and Normal Pregnant Women

- Effects of a supportive program on uncertainty, anxiety, and maternal-fetal attachment in women with high-risk pregnancy

- Serial mediation effects of social support and antepartum depression on the relationship between fetal attachment and anxiety in high-risk pregnant couples of South Korea

- The Mediating Effects of the Depression, Anxiety on the Relationship Between Temperament and Character and Maternal-Fetal Attachment in High-Risk Pregnant Women

- Effects of the Temperament and Character on Depression, Anxiety, and Maternal-Fetal Attachment in High-Risk Pregnant Women