Korean Circ J.

2021 Jul;51(7):561-578. 10.4070/kcj.2021.0104.

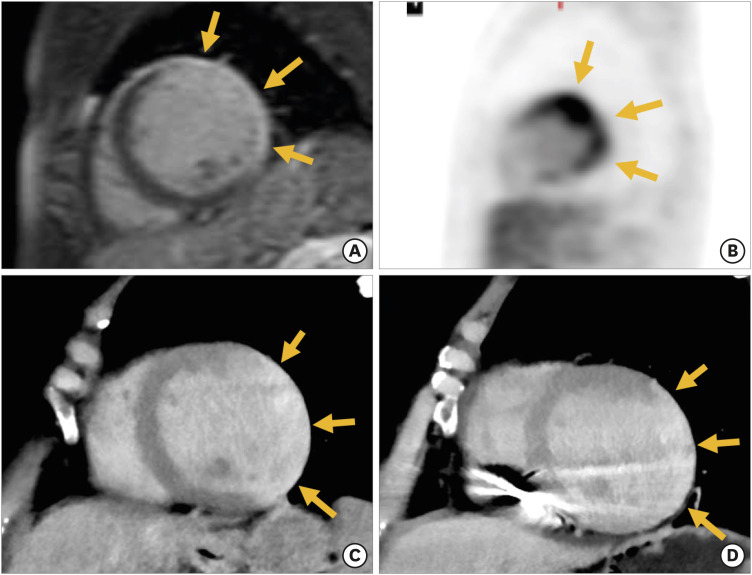

The Role of Multimodality Imaging in Cardiac Sarcoidosis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Radiology, Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan

- 2Department of Cardiology, Hokkaido Cardiovascular Hospital, Sapporo, Japan

- 3Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Hokkaido University Hospital, Sapporo, Japan

- KMID: 2517486

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2021.0104

Abstract

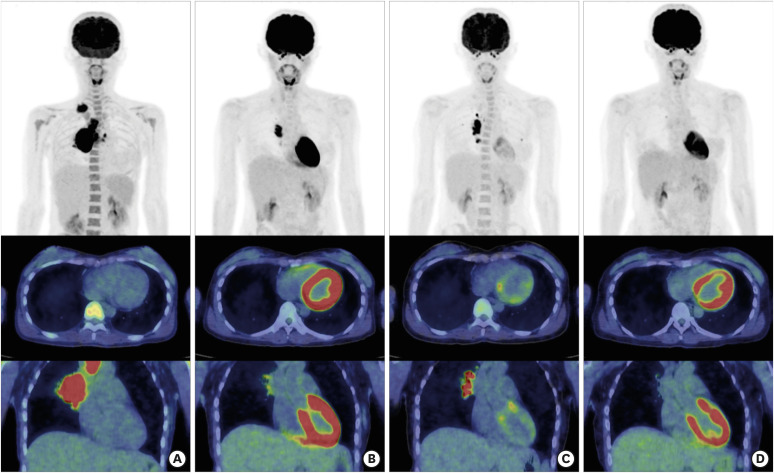

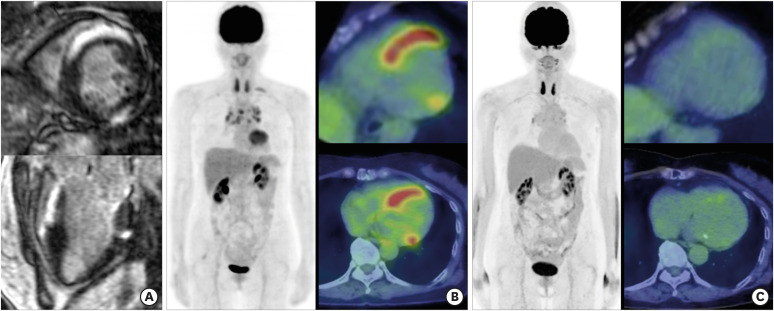

- The etiology and the progression of sarcoidosis remain unknown. However, cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is significantly associated with a poor prognosis due to the associated congestive heart failure, arrhythmias (such as an advanced atrioventricular block), and ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Novel imaging modalities are now available to detect CS lesions secondary to active inflammation, granuloma formation, and fibrotic changes. 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) play essential roles in diagnosing and monitoring patients with confirmed or suspected CS. The following focused review will highlight the emerging role of non-invasive cardiac imaging techniques, including FDG PET/ CT and CMR.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Left Ventricular Apical Aneurysm: Atypical Feature of Cardiac Sarcoidosis Diagnosed by Multimodality Imaging

Shin-Jae Kim, Soe Hee Ann, Yong-Giun Kim, Sangwoo Park

Korean Circ J. 2021;52(2):169-171. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0305.

Reference

-

1. Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:2153–2165. PMID: 18032765.

Article2. Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, et al. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999; 16:149–173. PMID: 10560120.3. Blankstein R, Osborne M, Naya M, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63:329–336. PMID: 24140661.

Article4. Patel MR, Cawley PJ, Heitner JF, et al. Detection of myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis. Circulation. 2009; 120:1969–1977. PMID: 19884472.

Article5. Costabel U, Hunninghake GW. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 1999; 14:735–737. PMID: 10573213.

Article6. Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis: recent advances and future prospects. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 28:22–35. PMID: 17330190.

Article7. Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:1224–1234. PMID: 9110911.

Article8. Greulich S, Deluigi CC, Gloekler S, et al. CMR imaging predicts death and other adverse events in suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013; 6:501–511. PMID: 23498675.

Article9. Blauwet LA, Cooper LT. Idiopathic giant cell myocarditis and cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2013; 18:733–746. PMID: 23111533.

Article10. Dubrey SW, Falk RH. Diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010; 52:336–346. PMID: 20109603.

Article11. Silverman KJ, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Cardiac sarcoid: a clinicopathologic study of 84 unselected patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Circulation. 1978; 58:1204–1211. PMID: 709777.

Article12. Iwai K, Tachibana T, Takemura T, Matsui Y, Kitaichi M, Kawabata Y. Pathological studies on sarcoidosis autopsy. I. Epidemiological features of 320 cases in Japan. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993; 43:372–376. PMID: 8372682.

Article13. Mehta D, Lubitz SA, Frankel Z, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: diagnostic and prognostic value of outpatient testing. Chest. 2008; 133:1426–1435. PMID: 18339784.14. Patel AR, Klein MR, Chandra S, et al. Myocardial damage in patients with sarcoidosis and preserved left ventricular systolic function: an observational study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011; 13:1231–1237. PMID: 21810833.

Article15. Vignaux O, Dhote R, Duboc D, et al. Detection of myocardial involvement in patients with sarcoidosis applying T2-weighted, contrast-enhanced, and cine magnetic resonance imaging: initial results of a prospective study. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002; 26:762–767. PMID: 12439312.

Article16. Hulten E, Aslam S, Osborne M, Abbasi S, Bittencourt MS, Blankstein R. Cardiac sarcoidosis-state of the art review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016; 6:50–63. PMID: 26885492.17. Tavora F, Cresswell N, Li L, Ripple M, Solomon C, Burke A. Comparison of necropsy findings in patients with sarcoidosis dying suddenly from cardiac sarcoidosis versus dying suddenly from other causes. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 104:571–577. PMID: 19660614.

Article18. Roberts WC, McAllister HA Jr, Ferrans VJ. Sarcoidosis of the heart. A clinicopathologic study of 35 necropsy patients (group 1) and review of 78 previously described necropsy patients (group 11). Am J Med. 1977; 63:86–108. PMID: 327806.19. Kandolin R, Lehtonen J, Graner M, et al. Diagnosing isolated cardiac sarcoidosis. J Intern Med. 2011; 270:461–468. PMID: 21535250.

Article20. Houston BA, Mukherjee M. Cardiac sarcoidosis: clinical manifestations, imaging characteristics, and therapeutic approach. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2014; 8:31–37. PMID: 25452702.

Article21. Sekhri V, Sanal S, Delorenzo LJ, Aronow WS, Maguire GP. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review. Arch Med Sci. 2011; 7:546–554. PMID: 22291785.

Article22. Chapelon-Abric C, de Zuttere D, Duhaut P, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a retrospective study of 41 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004; 83:315–334. PMID: 15525844.23. Matsui Y, Iwai K, Tachibana T, et al. Clinicopathological study of fatal myocardial sarcoidosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1976; 278:455–469. PMID: 1067031.24. Fleming HA, Bailey SM. Sarcoid heart disease. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1981; 15:245–246. 249–253. PMID: 7320964.

Article25. Terasaki F, Azuma A, Anzai T, et al. JCS 2016 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis - digest version. Circ J. 2019; 83:2329–2388. PMID: 31597819.26. Manabe O, Ohira H, Yoshinaga K, et al. Elevated 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the interventricular septum is associated with atrioventricular block in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013; 40:1558–1566. PMID: 23715906.27. Hiraga H, Iwai K, Hiroe M, Omori F, Sekiguchi M, Tachibana T. Guidelines for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: study report on diffuse pulmonary diseases [in Japanese]. Tokyo: The Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare;1993. p. 23–24.28. Diagnostic standard and guidelines for sarcoidosis. Jpn J Sarcoidosis Granulomatous Disord. 2007; 27:89–102.29. Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014; 11:1305–1323. PMID: 24819193.

Article30. Manabe O, Naya M, Aikawa T, Tamaki N. Recent advances in cardiac positron emission tomography for quantitative perfusion analyses and molecular imaging. Ann Nucl Med. 2020; 34:697–706. PMID: 32915386.

Article31. Manabe O, Yoshinaga K, Ohira H, et al. The effects of 18-h fasting with low-carbohydrate diet preparation on suppressed physiological myocardial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake and possible minimal effects of unfractionated heparin use in patients with suspected cardiac involvement sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2016; 23:244–252. PMID: 26243179.32. Yamada S, Kubota K, Kubota R, Ido T, Tamahashi N. High accumulation of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in turpentine-induced inflammatory tissue. J Nucl Med. 1995; 36:1301–1306. PMID: 7790960.33. Mochizuki T, Tsukamoto E, Kuge Y, et al. FDG uptake and glucose transporter subtype expressions in experimental tumor and inflammation models. J Nucl Med. 2001; 42:1551–1555. PMID: 11585872.34. Ning N, Guo HH, Iagaru A, Mittra E, Fowler M, Witteles R. Serial cardiac FDG-PET for the diagnosis and therapeutic guidance of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Card Fail. 2019; 25:307–311. PMID: 30825644.

Article35. Yoshinaga K, Manabe O, Ohira H, Tamaki N. Focus issue on cardiac sarcoidosis from international congress of nuclear cardiology and cardiac CT (ICNC 12) symposium: improving the detectability of cardiac sarcoidosis—practical aspects of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis—. Annals of Nuclear Cardiology. 2015; 1:87–94.36. Ishimaru S, Tsujino I, Takei T, et al. Focal uptake on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography images indicates cardiac involvement of sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:1538–1543. PMID: 15809286.37. Ito K, Okazaki O, Morooka M, Kubota K, Minamimoto R, Hiroe M. Visual findings of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Intern Med. 2014; 53:2041–2049. PMID: 25224185.

Article38. Manabe O, Ohira H, Hirata K, et al. Use of 18F-FDG PET/CT texture analysis to diagnose cardiac sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019; 46:1240–1247. PMID: 30327855.39. Okasha O, Kazmirczak F, Chen KA, Farzaneh-Far A, Shenoy C. Myocardial involvement in patients with histologically diagnosed cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of gross pathological images from autopsy or cardiac transplantation cases. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8:e011253. PMID: 31070111.

Article40. Coleman GC, Shaw PW, Balfour PC Jr, et al. Prognostic value of myocardial scarring on CMR in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; 10:411–420. PMID: 27450877.41. Hulten E, Agarwal V, Cahill M, et al. Presence of late gadolinium enhancement by cardiac magnetic resonance among patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis is associated with adverse cardiovascular prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 9:e005001. PMID: 27621357.

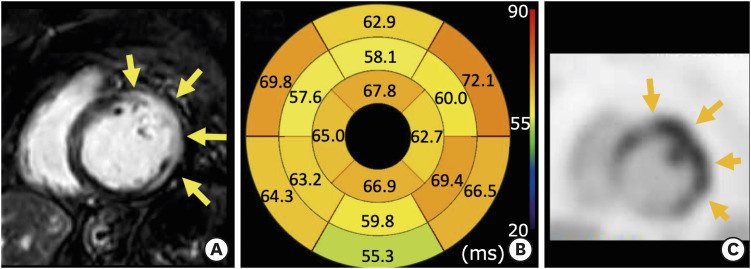

Article42. Tadic M, Cuspidi C, Saeed S, Milojevic B, Milojevic IG. The role of cardiac magnetic resonance in diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2021; 26:653–660. PMID: 33025413.

Article43. Greulich S, Kitterer D, Latus J, et al. Comprehensive cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment in patients with sarcoidosis and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016; 9:e005022. PMID: 27903537.

Article44. Puntmann VO, Isted A, Hinojar R, Foote L, Carr-White G, Nagel E. T1 and T2 mapping in recognition of early cardiac involvement in systemic sarcoidosis. Radiology. 2017; 285:63–72. PMID: 28448233.

Article45. Isted A, Grigoratos C, Bratis K, Carr-White G, Nagel E, Puntmann VO. Native T1 in deciphering the reversible myocardial inflammation in cardiac sarcoidosis with anti-inflammatory treatment. Int J Cardiol. 2016; 203:459–462. PMID: 26547739.

Article46. Gorcsan J 3rd, Tanaka H. Echocardiographic assessment of myocardial strain. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011; 58:1401–1413. PMID: 21939821.

Article47. Barssoum K, Altibi AM, Rai D, et al. Speckle tracking echocardiography can predict subclinical myocardial involvement in patients with sarcoidosis: a meta-analysis. Echocardiography. 2020; 37:2061–2070. PMID: 33058271.

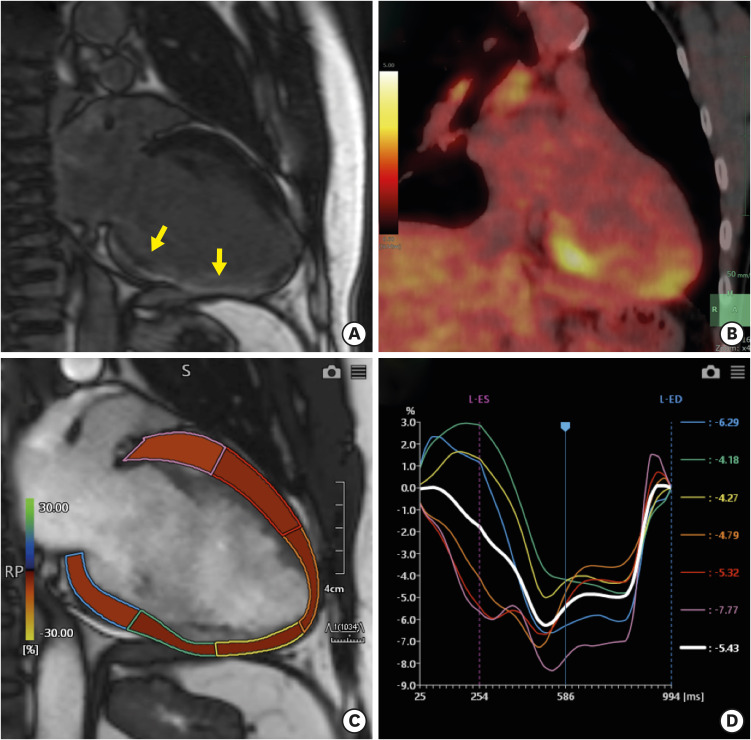

Article48. Kusunose K, Fujiwara M, Yamada H, et al. Deterioration of biventricular strain is an early marker of cardiac involvement in confirmed sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020; 21:796–804. PMID: 31566217.

Article49. Mordi I, Bezerra H, Carrick D, Tzemos N. The combined incremental prognostic value of LVEF, late gadolinium enhancement, and global circumferential strain assessed by CMR. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015; 8:540–549. PMID: 25890580.

Article50. Korosoglou G, Giusca S, Hofmann NP, et al. Strain-encoded magnetic resonance: a method for the assessment of myocardial deformation. ESC Heart Fail. 2019; 6:584–602. PMID: 31021534.

Article51. Oyama-Manabe N, Ishimori N, Sugimori H, et al. Identification and further differentiation of subendocardial and transmural myocardial infarction by fast strain-encoded (SENC) magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 Tesla. Eur Radiol. 2011; 21:2362–2368. PMID: 21688005.

Article52. Eitel I, Stiermaier T, Lange T, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance myocardial feature tracking for optimized prediction of cardiovascular events following myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 11:1433–1444. PMID: 29454776.

Article53. Nakano S, Kimura F, Osman N, et al. Improved myocardial strain measured by strain-encoded magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with cardiac sarcoidosis. Can J Cardiol. 2013; 29:1531.e9–1531.11.54. Backhaus SJ, Metschies G, Zieschang V, et al. Head-to-head comparison of cardiovascular MR feature tracking cine versus acquisition-based deformation strain imaging using myocardial tagging and strain encoding. Magn Reson Med. 2021; 85:357–368. PMID: 32851707.

Article55. Dabir D, Meyer D, Kuetting D, et al. Diagnostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance strain analysis for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. RoFo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed. 2018; 190:712–721. PMID: 30045396.

Article56. Yamagishi H, Shirai N, Takagi M, et al. Identification of cardiac sarcoidosis with 13N-NH3/18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003; 44:1030–1036. PMID: 12843216.57. Okumura W, Iwasaki T, Toyama T, et al. Usefulness of fasting 18F-FDG PET in identification of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med. 2004; 45:1989–1998. PMID: 15585472.58. Matoh F, Satoh H, Shiraki K, et al. The usefulness of delayed enhancement magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis and evaluation of cardiac function in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Cardiol. 2008; 51:179–188. PMID: 18522793.

Article59. Ohira H, Tsujino I, Ishimaru S, et al. Myocardial imaging with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008; 35:933–941. PMID: 18084757.60. Tahara N, Tahara A, Nitta Y, et al. Heterogeneous myocardial FDG uptake and the disease activity in cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010; 3:1219–1228. PMID: 21163450.

Article61. Manabe O, Yoshinaga K, Ohira H, et al. Right ventricular 18F-FDG uptake is an important indicator for cardiac involvement in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. Ann Nucl Med. 2014; 28:656–663. PMID: 24889126.62. Langah R, Spicer K, Gebregziabher M, Gordon L. Effectiveness of prolonged fasting 18F-FDG PET-CT in the detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009; 16:801–810. PMID: 19548047.63. Youssef G, Leung E, Mylonas I, et al. The use of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis: a systematic review and metaanalysis including the Ontario experience. J Nucl Med. 2012; 53:241–248. PMID: 22228794.64. Ambrosini V, Zompatori M, Fasano L, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT for the assessment of disease extension and activity in patients with sarcoidosis: results of a preliminary prospective study. Clin Nucl Med. 2013; 38:e171–7. PMID: 23429384.65. Mc Ardle BA, Birnie DH, Klein R, et al. Is there an association between clinical presentation and the location and extent of myocardial involvement of cardiac sarcoidosis as assessed by 18F- fluorodoexyglucose positron emission tomography? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013; 6:617–626. PMID: 23884290.66. Soussan M, Brillet PY, Nunes H, et al. Clinical value of a high-fat and low-carbohydrate diet before FDG-PET/CT for evaluation of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013; 20:120–127. PMID: 23188627.

Article67. Kobayashi S, Myoren T, Oda S, et al. Urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine as a novel biomarker of inflammatory activity in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 190:319–328. PMID: 25935620.

Article68. Momose M, Fukushima K, Kondo C, et al. Diagnosis and detection of myocardial injury in active cardiac sarcoidosis--significance of myocardial fatty acid metabolism and myocardial perfusion mismatch. Circ J. 2015; 79:2669–2676. PMID: 26477356.69. Orii M, Hirata K, Tanimoto T, et al. Comparison of cardiac MRI and 18F-FDG positron emission tomography manifestations and regional response to corticosteroid therapy in newly diagnosed cardiac sarcoidosis with complete heart block. Heart Rhythm. 2015; 12:2477–2485. PMID: 26111805.70. Simonen P, Lehtonen J, Kandolin R, et al. F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-guided sampling of mediastinal lymph nodes in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Am J Cardiol. 2015; 116:1581–1585. PMID: 26411357.

Article71. Yokoyama R, Miyagawa M, Okayama H, et al. Quantitative analysis of myocardial 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by PET/CT for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 195:180–187. PMID: 26043154.72. Gormsen LC, Haraldsen A, Kramer S, Dias AH, Kim WY, Borghammer P. A dual tracer 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT pilot study for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2016; 6:52. PMID: 27316444.

Article73. Ohira H, Birnie DH, Pena E, et al. Comparison of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) in corticosteroid-naive patients with conduction system disease due to cardiac sarcoidosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016; 43:259–269. PMID: 26359191.74. Ahmadian A, Pawar S, Govender P, Berman J, Ruberg FL, Miller EJ. The response of FDG uptake to immunosuppressive treatment on FDG PET/CT imaging for cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017; 24:413–424. PMID: 27457527.

Article75. Lee PI, Cheng G, Alavi A. The role of serial FDG PET for assessing therapeutic response in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017; 24:19–28. PMID: 27813028.

Article76. Norikane T, Yamamoto Y, Maeda Y, Noma T, Dobashi H, Nishiyama Y. Comparative evaluation of 18F-FLT and 18F-FDG for detecting cardiac and extra-cardiac thoracic involvement in patients with newly diagnosed sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res. 2017; 7:69. PMID: 28853043.

Article77. Yalagudri S, Zin Thu N, Devidutta S, et al. Tailored approach for management of ventricular tachycardia in cardiac sarcoidosis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017; 28:893–902. PMID: 28429512.

Article78. Furuya S, Manabe O, Ohira H, et al. Which is the proper reference tissue for measuring the change in FDG PET metabolic volume of cardiac sarcoidosis before and after steroid therapy? EJNMMI Res. 2018; 8:94. PMID: 30291527.

Article79. Lebasnier A, Legallois D, Bienvenu B, et al. Diagnostic value of quantitative assessment of cardiac 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose uptake in suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. Ann Nucl Med. 2018; 32:319–327. PMID: 29560563.80. Varghese M, Smiley D, Bellumkonda L, Rosenfeld LE, Zaret B, Miller EJ. Quantitative interpretation of FDG PET for cardiac sarcoidosis reclassifies visually interpreted exams and potentially impacts downstream interventions. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2018; 35:342–353. PMID: 32476922.81. Muser D, Santangeli P, Liang JJ, et al. Characterization of the electroanatomic substrate in cardiac sarcoidosis: correlation with imaging findings of scar and inflammation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018; 4:291–303. PMID: 30089553.82. Schildt JV, Loimaala AJ, Hippeläinen ET, Ahonen AA. Heterogeneity of myocardial 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake is a typical feature in cardiac sarcoidosis: a study of 231 patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 19:293–298. PMID: 28950301.

Article83. Divakaran S, Stewart GC, Lakdawala NK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of advanced imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019; 12:e008975. PMID: 31177817.

Article84. Furuya S, Naya M, Manabe O, et al. 18F-FMISO PET/CT detects hypoxic lesions of cardiac and extra-cardiac involvement in patients with sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019; [Epub ahead of print].85. Sgard B, Brillet PY, Bouvry D, et al. Evaluation of FDG PET combined with cardiac MRI for the diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of cardiac sarcoidosis. Clin Radiol. 2019; 74:81.e9–81.18.

Article86. Togo R, Hirata K, Manabe O, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis classification with deep convolutional neural network-based features using polar maps. Comput Biol Med. 2019; 104:81–86. PMID: 30447397.

Article87. Zipse MM, Tzou WS, Schuller JL, et al. Electrophysiologic testing for diagnostic evaluation and risk stratification in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis with preserved left and right ventricular systolic function. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019; 30:1939–1948. PMID: 31257683.

Article88. Higashi H, Inaba S, Iio C, et al. Features and clinical impact of extra-cardiac lesions with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020; 30:100587. PMID: 32743044.89. Kawai H, Sarai M, Kato Y, et al. Diagnosis of isolated cardiac sarcoidosis based on new guidelines. ESC Heart Fail. 2020; 7:2662–2671. PMID: 32578957.

Article90. Miller RJ, Cadet S, Pournazari P, et al. Quantitative assessment of cardiac hypermetabolism and perfusion for diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print].

Article91. Okune M, Yasuda M, Soejima N, et al. Diagnostic utility of fusion 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2020.

Article92. Wicks EC, Menezes LJ, Barnes A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic value of simultaneous hybrid 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 19:757–767. PMID: 29319785.93. Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis assessed at two university medical centers in the Netherlands. Chest. 2005; 128:30–35. PMID: 16002912.

Article94. Smedema JP, Snoep G, van Kroonenburgh MP, et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:1683–1690. PMID: 15893188.

Article95. Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, Kubo S, et al. Effectiveness of delayed enhanced MRI for identification of cardiac sarcoidosis: comparison with radionuclide imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 185:110–115. PMID: 15972409.

Article96. Ichinose A, Otani H, Oikawa M, et al. MRI of cardiac sarcoidosis: basal and subepicardial localization of myocardial lesions and their effect on left ventricular function. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008; 191:862–869. PMID: 18716120.

Article97. Manins V, Habersberger J, Pfluger H, Taylor AJ. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis: an Australian single-centre experience. Intern Med J. 2009; 39:77–82. PMID: 18771431.

Article98. Watanabe E, Kimura F, Nakajima T, et al. Late gadolinium enhancement in cardiac sarcoidosis: characteristic magnetic resonance findings and relationship with left ventricular function. J Thorac Imaging. 2013; 28:60–66. PMID: 23249970.99. Matsumoto K, Ehara S, Sakaguchi M, et al. Clinical characteristics of late gadolinium enhancement in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Osaka City Med J. 2015; 61:9–17. PMID: 26434101.100. Tezuka D, Terashima M, Kato Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of definite or suspected isolated cardiac sarcoidosis: application of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computerized tomography. J Card Fail. 2015; 21:313–322. PMID: 25512195.101. Komada T, Suzuki K, Ishiguchi H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis: an evaluation of the cardiac segments and layers that exhibit late gadolinium enhancement. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2016; 78:437–446. PMID: 28008199.102. Aikawa T, Oyama-Manabe N, Naya M, et al. Delayed contrast-enhanced computed tomography in patients with known or suspected cardiac sarcoidosis: a feasibility study. Eur Radiol. 2017; 27:4054–4063. PMID: 28382537.

Article103. Kataoka S, Momose M, Fukushima K, et al. Regional myocardial damage and active inflammation in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis detected by non-invasive multi-modal imaging. Ann Nucl Med. 2017; 31:135–143. PMID: 27804054.

Article104. Stanton KM, Ganigara M, Corte P, et al. The utility of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Lung Circ. 2017; 26:1191–1199. PMID: 28501519.

Article105. Smedema JP, van Geuns RJ, Truter R, Mayosi BM, Crijns HJ. Contrast-enhanced cardiac Magnetic Resonance: distinction between cardiac sarcoidosis and infarction scar. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017; 34:307–314. PMID: 32476863.106. Kouranos V, Tzelepis GE, Rapti A, et al. Complementary role of CMR to conventional screening in the diagnosis and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; 10:1437–1447. PMID: 28330653.

Article107. Ghanizada M, Rossing K, Bundgaard H, Gustafsson F. Clinical presentation, management and prognosis of patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. Dan Med J. 2018; 65:A5462. PMID: 29619923.108. Vita T, Okada DR, Veillet-Chowdhury M, et al. Complementary value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the assessment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018; 11:e007030. PMID: 29335272.

Article109. Darlington P, Gabrielsen A, Cederlund K, et al. Diagnostic approach for cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2019; 36:11–17. PMID: 32476931.110. Russo JJ, Nery PB, Ha AC, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of chest imaging for sarcoidosis screening in patients with cardiac presentations. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2019; 36:18–24. PMID: 32476932.111. Orii M, Tanimoto T, Ota S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for cardiac sarcoidosis in complete heart block patients implanted with magnetic resonance-conditional pacemaker. J Cardiol. 2020; 76:191–197. PMID: 32184028.

Article112. Narula J, Chandrashekhar Y, Ahmadi A, et al. SCCT 2021 expert consensus document on coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020; S1934-5925(20)30473-1.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Multi Modality Imaging Features of Cardiac Myxoma

- Heart Transplantation Performed in a Patient with Isolated Cardiac Sarcoidosis

- Left Ventricular Apical Aneurysm: Atypical Feature of Cardiac Sarcoidosis Diagnosed by Multimodality Imaging

- Myocardial Positron Emission Tomography for Evaluation of Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Specialized Protocols for Better Diagnosis

- Systemic Sarcoidosis Presenting with Arrhythmia