Korean J Physiol Pharmacol.

2021 May;25(3):227-237. 10.4196/kjpp.2021.25.3.227.

Carbon monoxide activates large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels of human cardiac fibroblasts through various mechanisms

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University, Seoul 06974, Korea

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chung-Ang University Hospital, Seoul 06973, Korea

- KMID: 2514948

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2021.25.3.227

Abstract

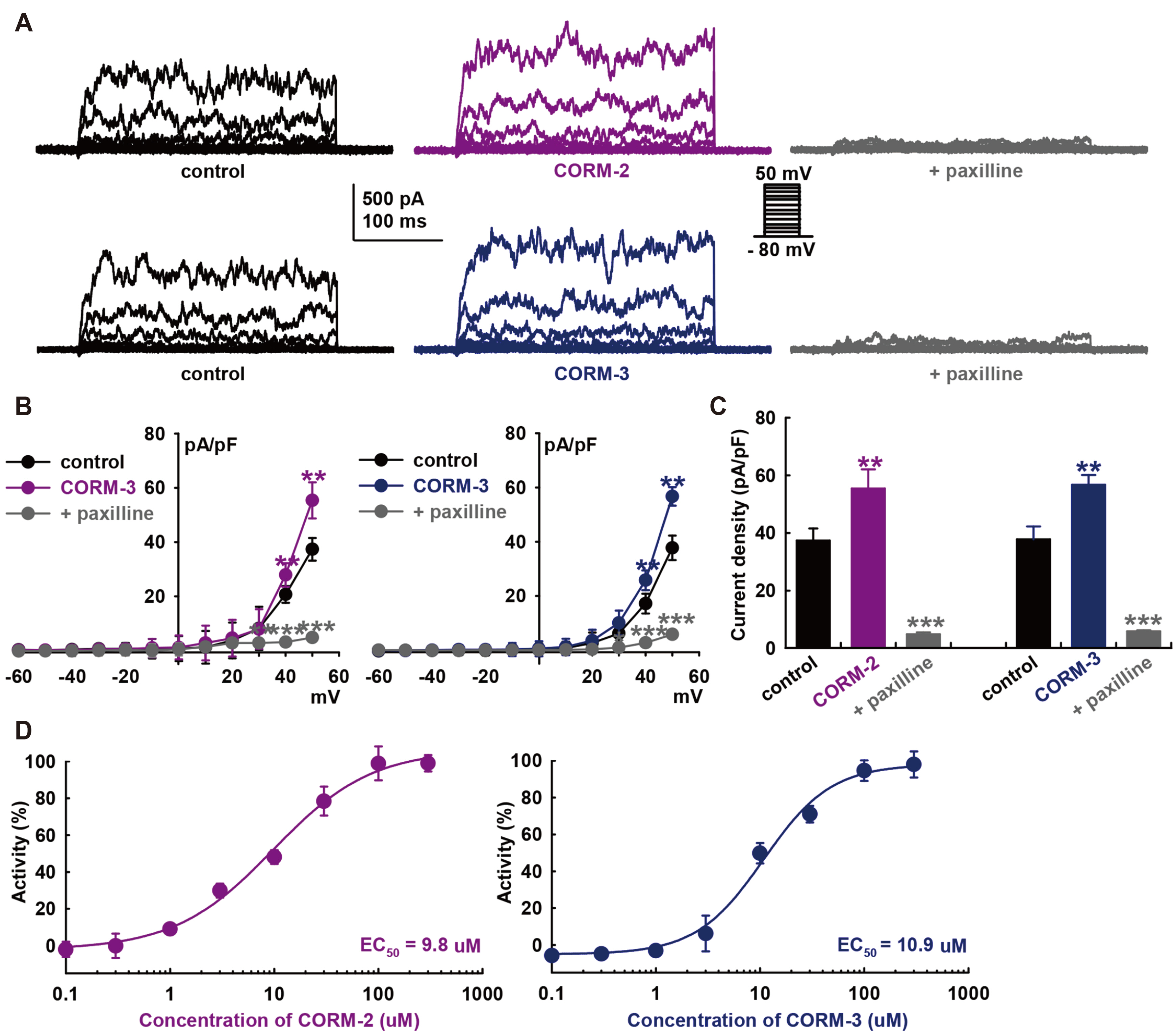

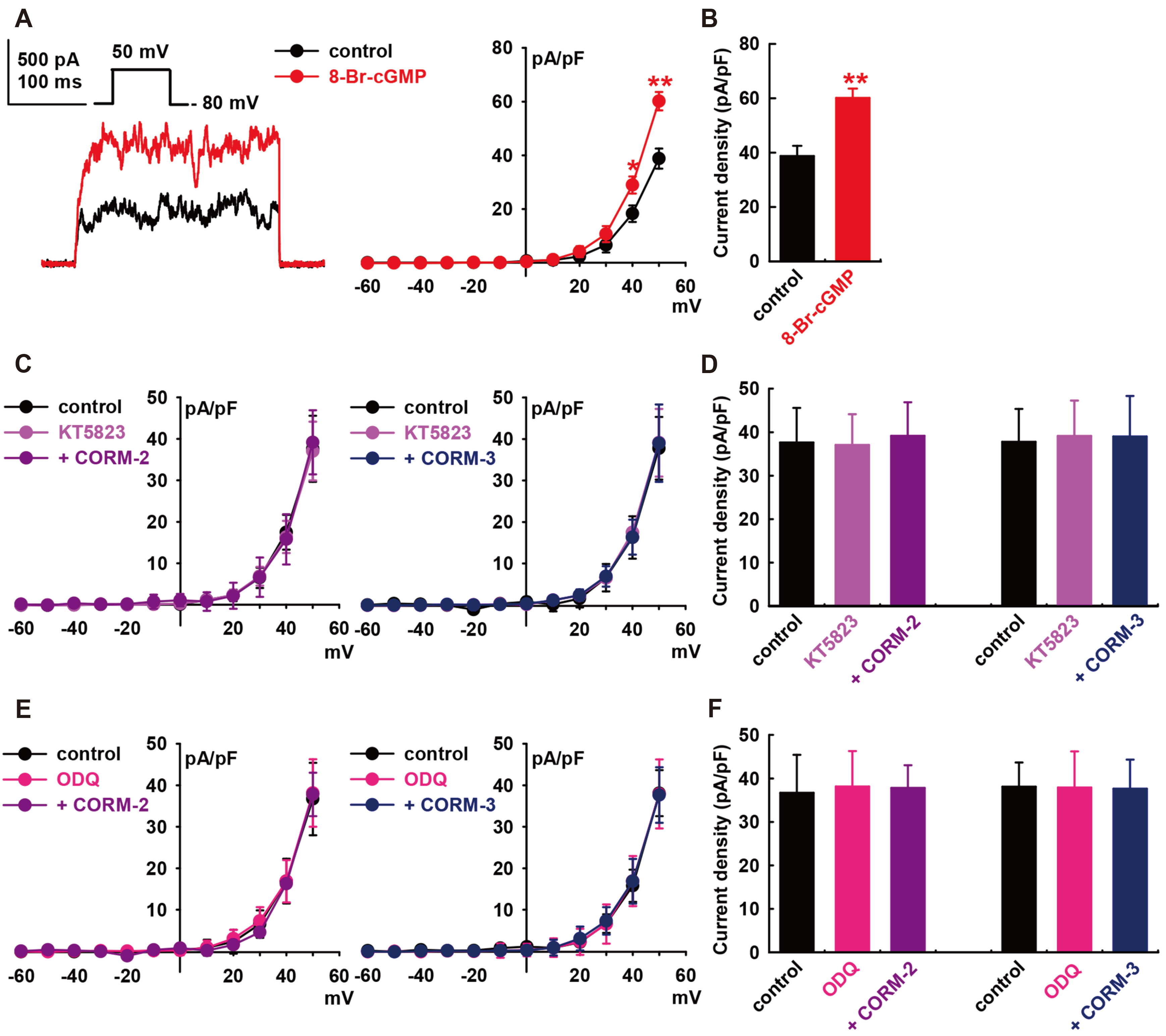

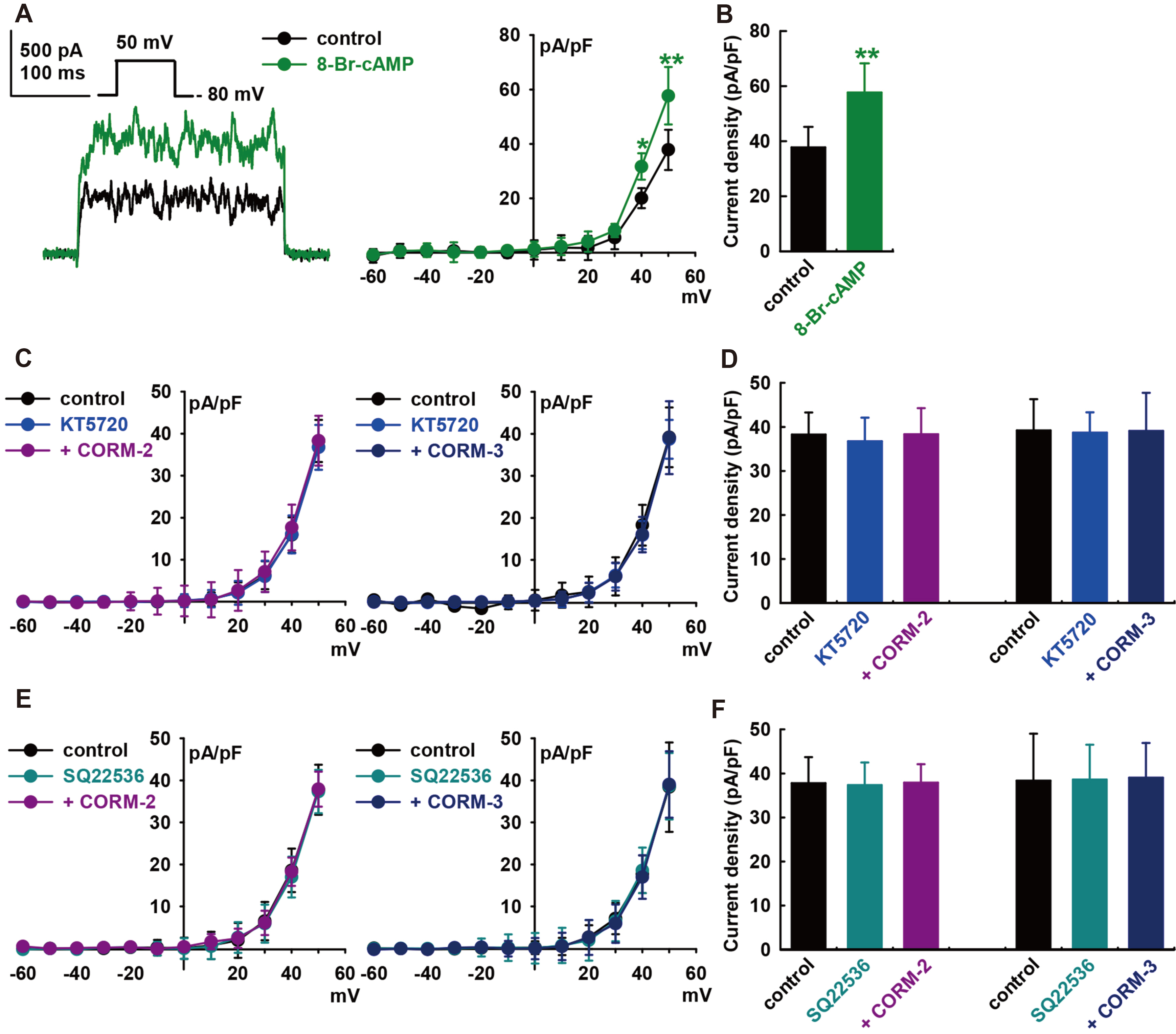

- Carbon monoxide (CO) is a cardioprotectant and potential cardiovascular therapeutic agent. Human cardiac fibroblasts (HCFs) are important determinants of myocardial structure and function. Large-conductance Ca 2+ -activated K+ (BK) channel is a potential therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. We investigated whether CO modulates BK channels and the signaling pathways in HCFs using whole-cell mode patch-clamp recordings. CO-releasing molecules (CORMs; CORM-2 and CORM-3) significantly increased the amplitudes of BK currents IBK. The CO-induced stimulating effects on IBK were blocked by pre-treatment with specific nitric oxide synthase (NOS) blockers (L-N G -monomethyl arginine citrate and L-N G -nitroarginine methyl ester). 8-bromo-cyclic GMP increased IBK. KT5823 (inhibits PKG) or ODQ (inhibits soluble guanylate cyclase) blocked the CO-stimulating effect on IBK. Moreover, 8-bromo-cyclic AMP also increased IBK, and pre-treatment with KT5720 (inhibits PKA) or SQ22536 (inhibits adenylate cyclase) blocked the CO effect. Pre-treatment with Nethylmaleimide (a thiol-alkylating reagent) also blocked the CO effect on IBK, and DLdithiothreitol (a reducing agent) reversed the CO effect. These data suggest that CO activates IBK through NO via the NOS and through the PKG, PKA, and S-nitrosylation pathways.

Figure

Cited by 1 articles

-

Carbon monoxide activation of delayed rectifier potassium currents of human cardiac fibroblasts through diverse pathways

Hyemi Bae, Taeho Kim, Inja Lim

Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2022;26(1):25-36. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.1.25.

Reference

-

1. Marchewka J, Gawlik I, Dębski G, Popiołek L, Marchewka W, Hydzik P. 2017; Cardiological aspects of carbon monoxide poisoning. Folia Med Cracov. 57:75–85. PMID: 28608865.2. Peers C, Steele DS. 2012; Carbon monoxide: a vital signalling molecule and potent toxin in the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 52:359–365. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.05.013. PMID: 21640728.

Article3. André L, Gouzi F, Thireau J, Meyer G, Boissiere J, Delage M, Abdellaoui A, Feillet-Coudray C, Fouret G, Cristol JP, Lacampagne A, Obert P, Reboul C, Fauconnier J, Hayot M, Richard S, Cazorla O. 2011; Carbon monoxide exposure enhances arrhythmia after cardiac stress: involvement of oxidative stress. Basic Res Cardiol. 106:1235–1246. DOI: 10.1007/s00395-011-0211-y. PMID: 21822772.

Article4. Dallas ML, Yang Z, Boyle JP, Boycott HE, Scragg JL, Milligan CJ, Elies J, Duke A, Thireau J, Reboul C, Richard S, Bernus O, Steele DS, Peers C. 2012; Carbon monoxide induces cardiac arrhythmia via induction of the late Na+ current. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 186:648–656. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0688OC. PMID: 22822026. PMCID: PMC3622900.5. Gandini C, Castoldi AF, Candura SM, Locatelli C, Butera R, Priori S, Manzo L. 2001; Carbon monoxide cardiotoxicity. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 39:35–44. DOI: 10.1081/CLT-100102878. PMID: 11327225.

Article6. Motterlini R, Foresti R. 2017; Biological signaling by carbon monoxide and carbon monoxide-releasing molecules. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 312:C302–C313. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00360.2016. PMID: 28077358.

Article7. Otterbein LE, Foresti R, Motterlini R. 2016; Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in the heart: the balancing act between danger signaling and pro-survival. Circ Res. 118:1940–1959. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306588. PMID: 27283533. PMCID: PMC4905590.8. Lakkisto P, Siren JM, Kytö V, Forsten H, Laine M, Pulkki K, Tikkanen I. 2011; Heme oxygenase-1 induction protects the heart and modulates cellular and extracellular remodelling after myocardial infarction in rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 236:1437–1448. DOI: 10.1258/ebm.2011.011148. PMID: 22087023.

Article9. Ewing JF, Raju VS, Maines MD. 1994; Induction of heart heme oxygenase-1 (HSP32) by hyperthermia: possible role in stress-mediated elevation of cyclic 3':5'-guanosine monophosphate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 271:408–414. PMID: 7525927.10. Ling K, Men F, Wang WC, Zhou YQ, Zhang HW, Ye DW. 2018; Carbon monoxide and its controlled release: therapeutic application, detection, and development of carbon monoxide releasing molecules (CORMs). J Med Chem. 61:2611–2635. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01153. PMID: 28876065.

Article11. Akamatsu Y, Haga M, Tyagi S, Yamashita K, Graça-Souza AV, Ollinger R, Czismadia E, May GA, Ifedigbo E, Otterbein LE, Bach FH, Soares MP. 2004; Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide protects hearts from transplant associated ischemia reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 18:771–772. DOI: 10.1096/fj.03-0921fje. PMID: 14977880.12. Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. 2009; Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res. 105:1164–1176. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. PMID: 19959782. PMCID: PMC3345531.13. Kohl P. 2003; Heterogeneous cell coupling in the heart: an electrophysiological role for fibroblasts. Circ Res. 93:381–383. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091364.90121.0C. PMID: 12958139.14. Villarreal FJ, Kim NN. 1998; Regulation of myocardial extracellular matrix components by mechanical and chemical growth factors. Cardiovasc Pathol. 7:145–151. DOI: 10.1016/S1054-8807(97)00122-1. PMID: 25851221.

Article15. Pellman J, Zhang J, Sheikh F. 2016; Myocyte-fibroblast communication in cardiac fibrosis and arrhythmias: mechanisms and model systems. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 94:22–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.03.005. PMID: 26996756. PMCID: PMC4861678.

Article16. Camelliti P, Green CR, LeGrice I, Kohl P. 2004; Fibroblast network in rabbit sinoatrial node: structural and functional identification of homogeneous and heterogeneous cell coupling. Circ Res. 94:828–835. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000122382.19400.14. PMID: 14976125.17. Cartledge JE, Kane C, Dias P, Tesfom M, Clarke L, Mckee B, Al Ayoubi S, Chester A, Yacoub MH, Camelliti P, Terracciano CM. 2015; Functional crosstalk between cardiac fibroblasts and adult cardiomyocytes by soluble mediators. Cardiovasc Res. 105:260–270. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvu264. PMID: 25560320.

Article18. Gaudesius G, Miragoli M, Thomas SP, Rohr S. 2003; Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circ Res. 93:421–428. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089258.40661.0C. PMID: 12893743.

Article19. Vasquez C, Benamer N, Morley GE. 2011; The cardiac fibroblast: functional and electrophysiological considerations in healthy and diseased hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 57:380–388. DOI: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31820cda19. PMID: 21242811. PMCID: PMC3077441.

Article20. Vasquez C, Mohandas P, Louie KL, Benamer N, Bapat AC, Morley GE. 2010; Enhanced fibroblast-myocyte interactions in response to cardiac injury. Circ Res. 107:1011–1020. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227421. PMID: 20705922. PMCID: PMC2993566.

Article21. Bae H, Lee D, Kim YW, Choi J, Lee HJ, Kim SW, Kim T, Noh YH, Ko JH, Bang H, Lim I. 2016; Effects of hydrogen peroxide on voltage-dependent K+ currents in human cardiac fibroblasts through protein kinase pathways. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 20:315–324. DOI: 10.4196/kjpp.2016.20.3.315. PMID: 27162486. PMCID: PMC4860374.22. Li GR, Sun HY, Chen JB, Zhou Y, Tse HF, Lau CP. 2009; Characterization of multiple ion channels in cultured human cardiac fibroblasts. PLoS One. 4:e7307. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007307. PMID: 19806193. PMCID: PMC2751830.

Article23. Wang YJ, Sung RJ, Lin MW, Wu SN. 2006; Contribution of BKCa-channel activity in human cardiac fibroblasts to electrical coupling of cardiomyocytes-fibroblasts. J Membr Biol. 213:175–185. DOI: 10.1007/s00232-007-0027-8. PMID: 17483867.24. Mahoney VM, Mezzano V, Morley GE. 2016; A review of the literature on cardiac electrical activity between fibroblasts and myocytes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 120:128–133. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.12.006. PMID: 26713556. PMCID: PMC4808420.

Article25. Bae H, Lim I. 2017; Effects of nitric oxide on large-conductance Ca2+ -activated K+ currents in human cardiac fibroblasts through PKA and PKG-related pathways. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 44:1116–1124. DOI: 10.1111/1440-1681.12817. PMID: 28731589.26. Chilton L, Ohya S, Freed D, George E, Drobic V, Shibukawa Y, Maccannell KA, Imaizumi Y, Clark RB, Dixon IM, Giles WR. 2005; K+ currents regulate the resting membrane potential, proliferation, and contractile responses in ventricular fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 288:H2931–H2939. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.01220.2004. PMID: 15653752.27. Hu XQ, Zhang L. 2012; Function and regulation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel in vascular smooth muscle cells. Drug Discov Today. 17:974–987. DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.04.002. PMID: 22521666. PMCID: PMC3414640.28. Balderas E, Zhang J, Stefani E, Toro L. 2015; Mitochondrial BKCa channel. Front Physiol. 6:104. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00104. PMID: 25873902. PMCID: PMC4379900.29. Kim HH, Choi S. 2018; Therapeutic aspects of carbon monoxide in cardiovascular disease. Int J Mol Sci. 19:2381. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19082381. PMID: 30104479. PMCID: PMC6121498.

Article30. Kapetanaki SM, Burton MJ, Basran J, Uragami C, Moody PCE, Mitcheson JS, Schmid R, Davies NW, Dorlet P, Vos MH, Storey NM, Raven E. 2018; A mechanism for CO regulation of ion channels. Nat Commun. 9:907. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03291-z. PMID: 29500353. PMCID: PMC5834611.

Article31. Wilkinson WJ, Kemp PJ. 2011; Carbon monoxide: an emerging regulator of ion channels. J Physiol. 589(Pt 13):3055–3062. DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206706. PMID: 21521759. PMCID: PMC3145923.

Article32. Peers C. 2012; Modulation of ion channels and transporters by carbon monoxide: causes for concern? Front Physiol. 3:477. DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00477. PMID: 23267333. PMCID: PMC3526770.

Article33. Peers C, Boyle JP, Scragg JL, Dallas ML, Al-Owais MM, Hettiarachichi NT, Elies J, Johnson E, Gamper N, Steele DS. 2015; Diverse mechanisms underlying the regulation of ion channels by carbon monoxide. Br J Pharmacol. 172:1546–1556. DOI: 10.1111/bph.12760. PMID: 24818840. PMCID: PMC4369263.

Article34. Dong DL, Zhang Y, Lin DH, Chen J, Patschan S, Goligorsky MS, Nasjletti A, Yang BF, Wang WH. 2007; Carbon monoxide stimulates the Ca2+-activated big conductance k channels in cultured human endothelial cells. Hypertension. 50:643–651. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.096057. PMID: 17724275.35. Wang R, Wu L, Wang Z. 1997; The direct effect of carbon monoxide on KCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 434:285–291. DOI: 10.1007/s004240050398. PMID: 9178628.36. Lim I, Gibbons SJ, Lyford GL, Miller SM, Strege PR, Sarr MG, Chatterjee S, Szurszewski JH, Shah VH, Farrugia G. 2005; Carbon monoxide activates human intestinal smooth muscle L-type Ca2+ channels through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 288:G7–G14. DOI: 10.1152/ajpgi.00205.2004. PMID: 15319183.37. Hartsfield CL. 2002; Cross talk between carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 4:301–307. DOI: 10.1089/152308602753666352. PMID: 12006181.

Article38. Rotko D, Bednarczyk P, Koprowski P, Kunz WS, Szewczyk A, Kulawiak B. 2020; Heme is required for carbon monoxide activation of mitochondrial BKCa channel. Eur J Pharmacol. 881:173191. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173191. PMID: 32422186.39. Zhou Y, Lingle CJ. 2014; Paxilline inhibits BK channels by an almost exclusively closed-channel block mechanism. J Gen Physiol. 144:415–440. DOI: 10.1085/jgp.201411259. PMID: 25348413. PMCID: PMC4210426.

Article40. Xu W, Liu Y, Wang S, McDonald T, Van Eyk JE, Sidor A, O'Rourke B. 2002; Cytoprotective role of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in the cardiac inner mitochondrial membrane. Science. 298:1029–1033. DOI: 10.1126/science.1074360. PMID: 12411707.41. Singh H, Lu R, Bopassa JC, Meredith AL, Stefani E, Toro L. 2013; MitoBKCa is encoded by the Kcnma1 gene, and a splicing sequence defines its mitochondrial location. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:10836–10841. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1302028110. PMID: 23754429. PMCID: PMC3696804.42. Dong DL, Bai YL, Cai BZ. 2016; Calcium-activated potassium channels: potential target for cardiovascular diseases. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 104:233–261. DOI: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.11.007. PMID: 27038376.43. Decaluwé K, Pauwels B, Verpoest S, Van de Voorde J. 2012; Divergent mechanisms involved in CO and CORM-2 induced vasorelaxation. Eur J Pharmacol. 674:370–377. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.11.004. PMID: 22108549.

Article44. Bihari A, Chung KA, Cepinskas G, Sanders D, Schemitsch E, Lawendy AR. 2019; Carbon monoxide-releasing molecule-3 (CORM-3) offers protection in an in vitro model of compartment syndrome. Microcirculation. 26:e12577. DOI: 10.1111/micc.12577. PMID: 31230399.

Article45. Motterlini R. 2007; Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules (CO-RMs): vasodilatory, anti-ischaemic and anti-inflammatory activities. Biochem Soc Trans. 35(Pt 5):1142–1146. DOI: 10.1042/BST0351142. PMID: 17956297.

Article46. Portal L, Morin D, Motterlini R, Ghaleh B, Pons S. 2019; The CO-releasing molecule CORM-3 protects adult cardiomyocytes against hypoxia-reoxygenation by modulating pH restoration. Eur J Pharmacol. 862:172636. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172636. PMID: 31491405.

Article47. Wilkinson WJ, Kemp PJ. 2011; The carbon monoxide donor, CORM-2, is an antagonist of ATP-gated, human P2X4 receptors. Purinergic Signal. 7:57–64. DOI: 10.1007/s11302-010-9213-8. PMID: 21484097. PMCID: PMC3083130.

Article48. Musameh MD, Fuller BJ, Mann BE, Green CJ, Motterlini R. 2006; Positive inotropic effects of carbon monoxide-releasing molecules (CO-RMs) in the isolated perfused rat heart. Br J Pharmacol. 149:1104–1112. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706939. PMID: 17057755. PMCID: PMC2014642.

Article49. Al-Owais MM, Hettiarachchi NT, Boyle JP, Scragg JL, Elies J, Dallas ML, Lippiat JD, Steele DS, Peers C. 2017; Multiple mechanisms mediating carbon monoxide inhibition of the voltage-gated K+ channel Kv1.5. Cell Death Dis. 8:e3163. DOI: 10.1038/cddis.2017.568. PMID: 29095440. PMCID: PMC5775415.50. Polte T, Abate A, Dennery PA, Schröder H. 2000; Heme oxygenase-1 is a cGMP-inducible endothelial protein and mediates the cytoprotective action of nitric oxide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 20:1209–1215. DOI: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.5.1209. PMID: 10807735.

Article51. Durante W, Kroll MH, Christodoulides N, Peyton KJ, Schafer AI. 1997; Nitric oxide induces heme oxygenase-1 gene expression and carbon monoxide production in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 80:557–564. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.80.4.557. PMID: 9118487.

Article52. Ingi T, Cheng J, Ronnett GV. 1996; Carbon monoxide: an endogenous modulator of the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP signaling system. Neuron. 16:835–842. DOI: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80103-8. PMID: 8608001.

Article53. Cao L, Blute TA, Eldred WD. 2000; Localization of heme oxygenase-2 and modulation of cGMP levels by carbon monoxide and/or nitric oxide in the retina. Vis Neurosci. 17:319–329. DOI: 10.1017/S0952523800173018. PMID: 10910101.

Article54. Gustafsson AB, Brunton LL. 2002; Attenuation of cAMP accumulation in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts by IL-1beta and NO: role of cGMP-stimulated PDE2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 283:C463–471. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00299.2001. PMID: 12107056.55. Núñez L, Vaquero M, Gómez R, Caballero R, Mateos-Cáceres P, Macaya C, Iriepa I, Gálvez E, López-Farré A, Tamargo J, Delpón E. 2006; Nitric oxide blocks hKv1.5 channels by S-nitrosylation and by a cyclic GMP-dependent mechanism. Cardiovasc Res. 72:80–89. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.021. PMID: 16876149.56. White RE, Kryman JP, El-Mowafy AM, Han G, Carrier GO. 2000; cAMP-dependent vasodilators cross-activate the cGMP-dependent protein kinase to stimulate BKCa channel activity in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 86:897–905. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.86.8.897. PMID: 10785513.57. Gonzalez DR, Treuer A, Sun QA, Stamler JS, Hare JM. 2009; S-Nitrosylation of cardiac ion channels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 54:188–195. DOI: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181b72c9f. PMID: 19687749. PMCID: PMC3390783.

Article58. Lima B, Forrester MT, Hess DT, Stamler JS. 2010; S-nitrosylation in cardiovascular signaling. Circ Res. 106:633–646. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207381. PMID: 20203313. PMCID: PMC2891248.

Article59. Martínez-Ruiz A, Lamas S. 2004; S-nitrosylation: a potential new paradigm in signal transduction. Cardiovasc Res. 62:43–52. DOI: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.013. PMID: 15023551.

Article60. Ahern GP, Hsu SF, Klyachko VA, Jackson MB. 2000; Induction of persistent sodium current by exogenous and endogenous nitric oxide. J Biol Chem. 275:28810–28815. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M003090200. PMID: 10833522.

Article61. Yue ZJ, Xu PT, Jiao B, Chang H, Song Z, Xie MJ, Yu ZB. 2015; Nitric oxide protects L-type calcium channel of cardiomyocyte during long-term isoproterenol stimulation in tail-suspended rats. Biomed Res Int. 2015:780814. DOI: 10.1155/2015/780814. PMID: 26167497. PMCID: PMC4488016.

Article62. Sun J, Picht E, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. 2006; Hypercontractile female hearts exhibit increased S-nitrosylation of the L-type Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit and reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res. 98:403–411. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202707.79018.0a. PMID: 16397145.63. Bai CX, Namekata I, Kurokawa J, Tanaka H, Shigenobu K, Furukawa T. 2005; Role of nitric oxide in Ca2+ sensitivity of the slowly activating delayed rectifier K+ current in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 96:64–72. DOI: 10.1161/01.RES.0000151846.19788.E0. PMID: 15569827.64. Bai CX, Takahashi K, Masumiya H, Sawanobori T, Furukawa T. 2004; Nitric oxide-dependent modulation of the delayed rectifier K+ current and the L-type Ca2+ current by ginsenoside Re, an ingredient of Panax ginseng, in guinea-pig cardiomyocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 142:567–575. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705814. PMID: 15148247. PMCID: PMC1574975.65. Gómez R, Núñez L, Vaquero M, Amorós I, Barana A, de Prada T, Macaya C, Maroto L, Rodríguez E, Caballero R, López-Farré A, Tamargo J, Delpón E. 2008; Nitric oxide inhibits Kv4.3 and human cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito1). Cardiovasc Res. 80:375–384. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvn205. PMID: 18678642.66. Lai MH, Wu Y, Gao Z, Anderson ME, Dalziel JE, Meredith AL. 2014; BK channels regulate sinoatrial node firing rate and cardiac pacing in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 307:H1327–H1338. DOI: 10.1152/ajpheart.00354.2014. PMID: 25172903. PMCID: PMC4217012.

Article67. Kohl P, Gourdie RG. 2014; Fibroblast-myocyte electrotonic coupling: does it occur in native cardiac tissue? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 70:37–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.024. PMID: 24412581. PMCID: PMC4001130.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Alterations in Calcium-Activated Potassium Channel Expressions in Human Prostate Cancer

- Modulation of Large Conductance Ca2+-activated K+ Channel of Skin Fibroblast (CRL-1474) by Cyclic Nucleotides

- Effects of Phytoestrogen on Potassium Channel Activities of Smooth Muscle Cells of Rabbit Seminal Vesicle

- The large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel holds the key to the conundrum of familial hypokalemic periodic paralysis

- Identification of a Calcium-activated Potassium Channel Gene Expressed in Rat Cardiac Myocytes