J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci.

2020 Sep;36(3):158-167. 10.14368/jdras.2020.36.3.158.

Infection control of dental implant hand drivers using ethanol solution

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Prosthodontics, College of Dentistry, Wonkwang University, Iksan, Republic of Korea

- KMID: 2512110

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.14368/jdras.2020.36.3.158

Abstract

- Purpose

The purpose of this study was to study the effects of the utilization of ethanol solution in infection control of dental implant hand drivers, a common practice in dental prosthodontic clinics.

Materials and Methods

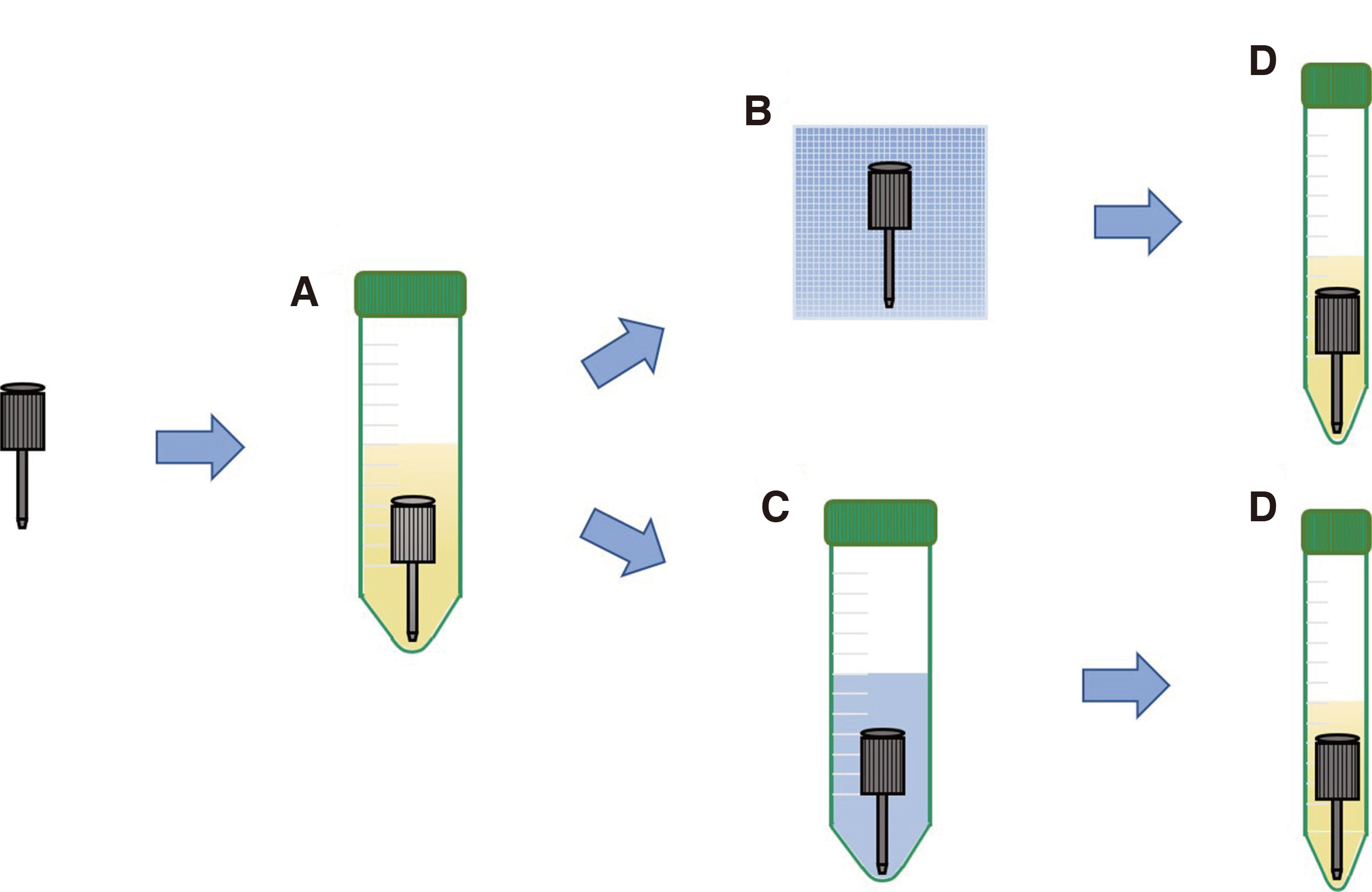

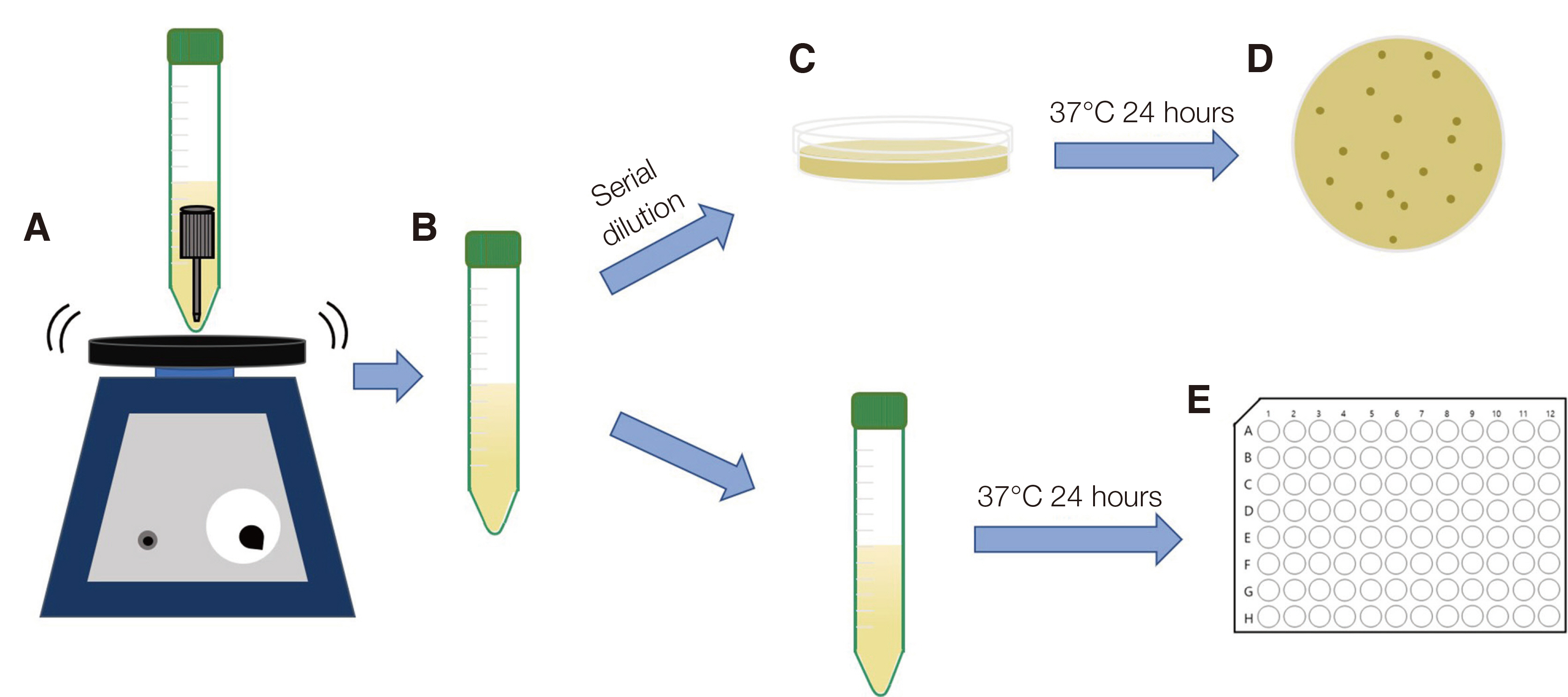

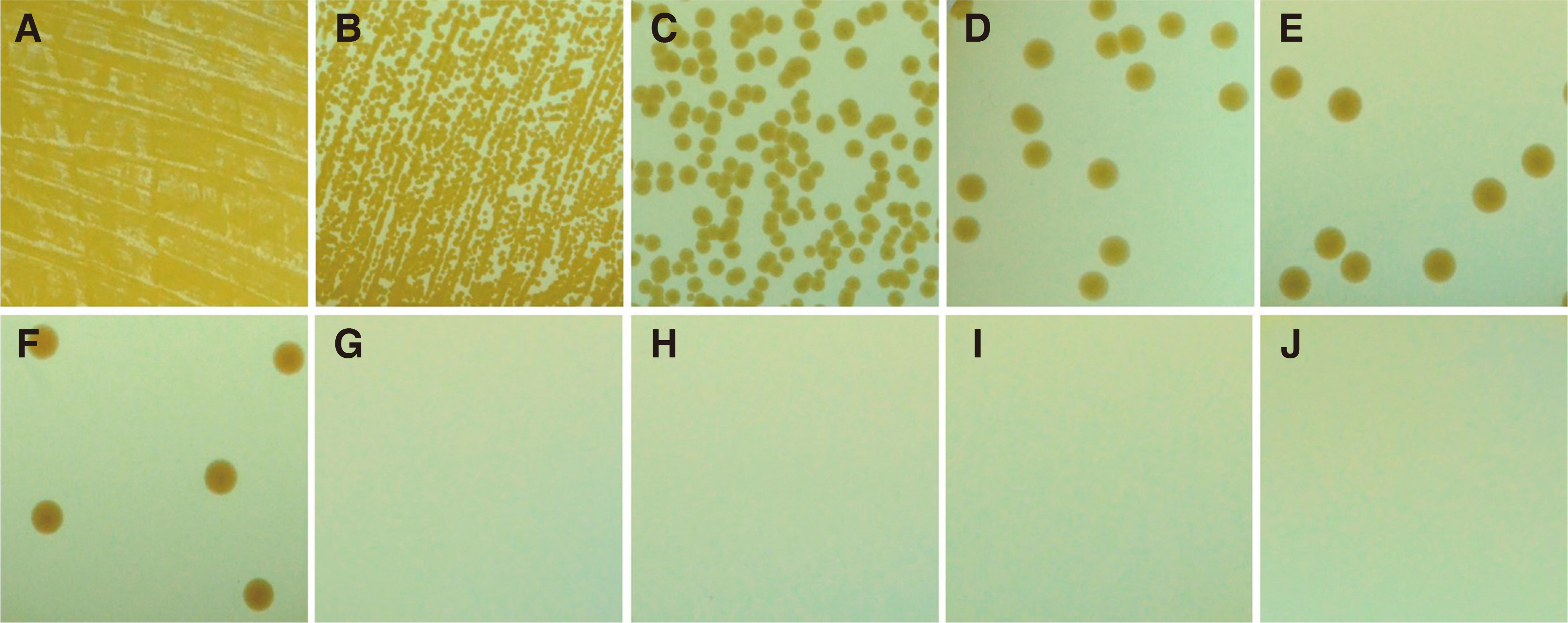

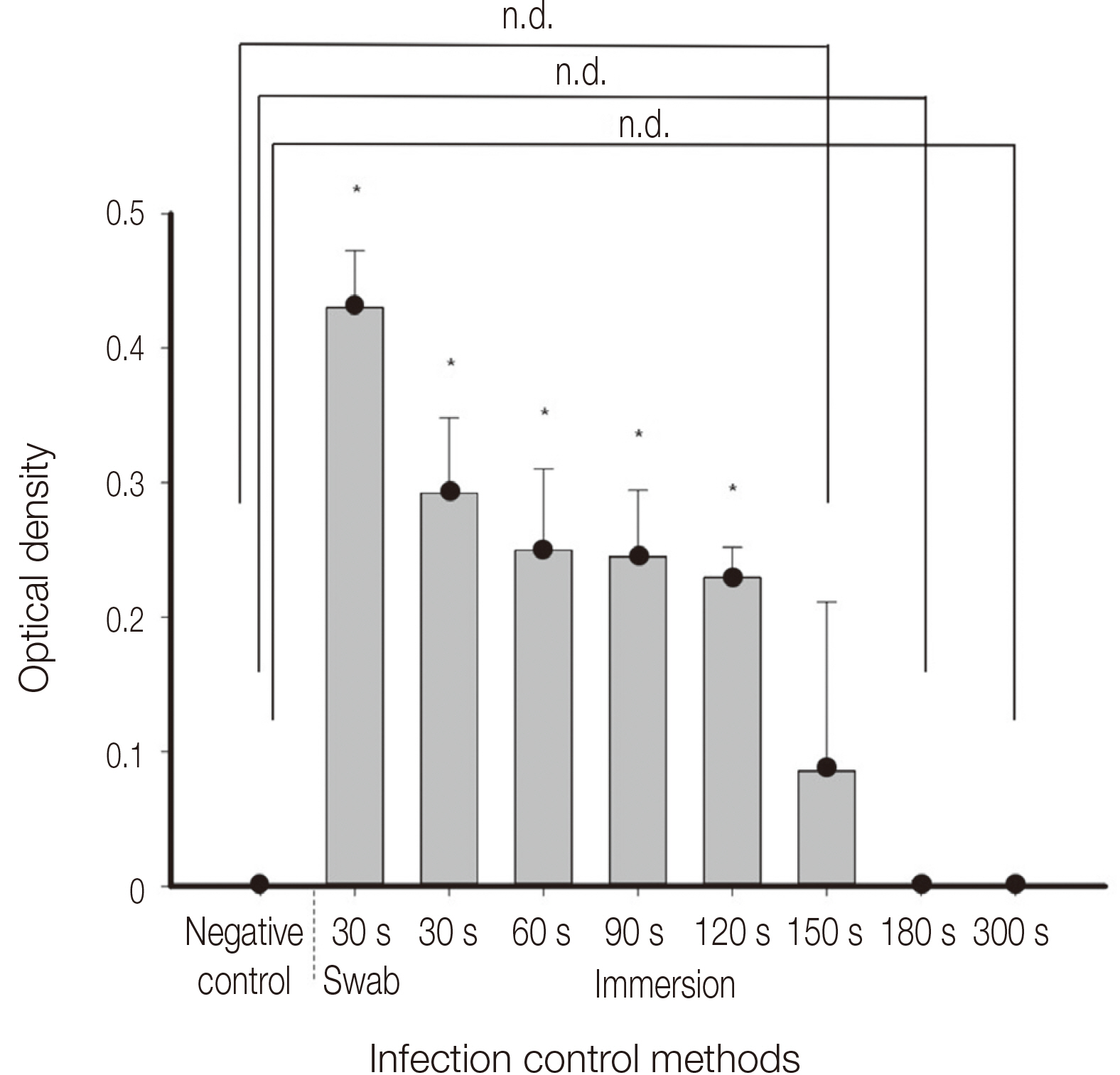

Infection control methods were divided into two groups. One swabbed with 83% ethanol gauze and the other immersed in 83% ethanol solution for 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180 and 300 second intervals after inoculation of the dental implant hand drivers with Staphylococcus aureus. After measuring the number of colony forming units and analyzing the optical density, the effects of infection control in the experimental group were compared with the positive control group without infection control after inoculation with bacteria and the negative control group without inoculation with bacteria after sterilization.

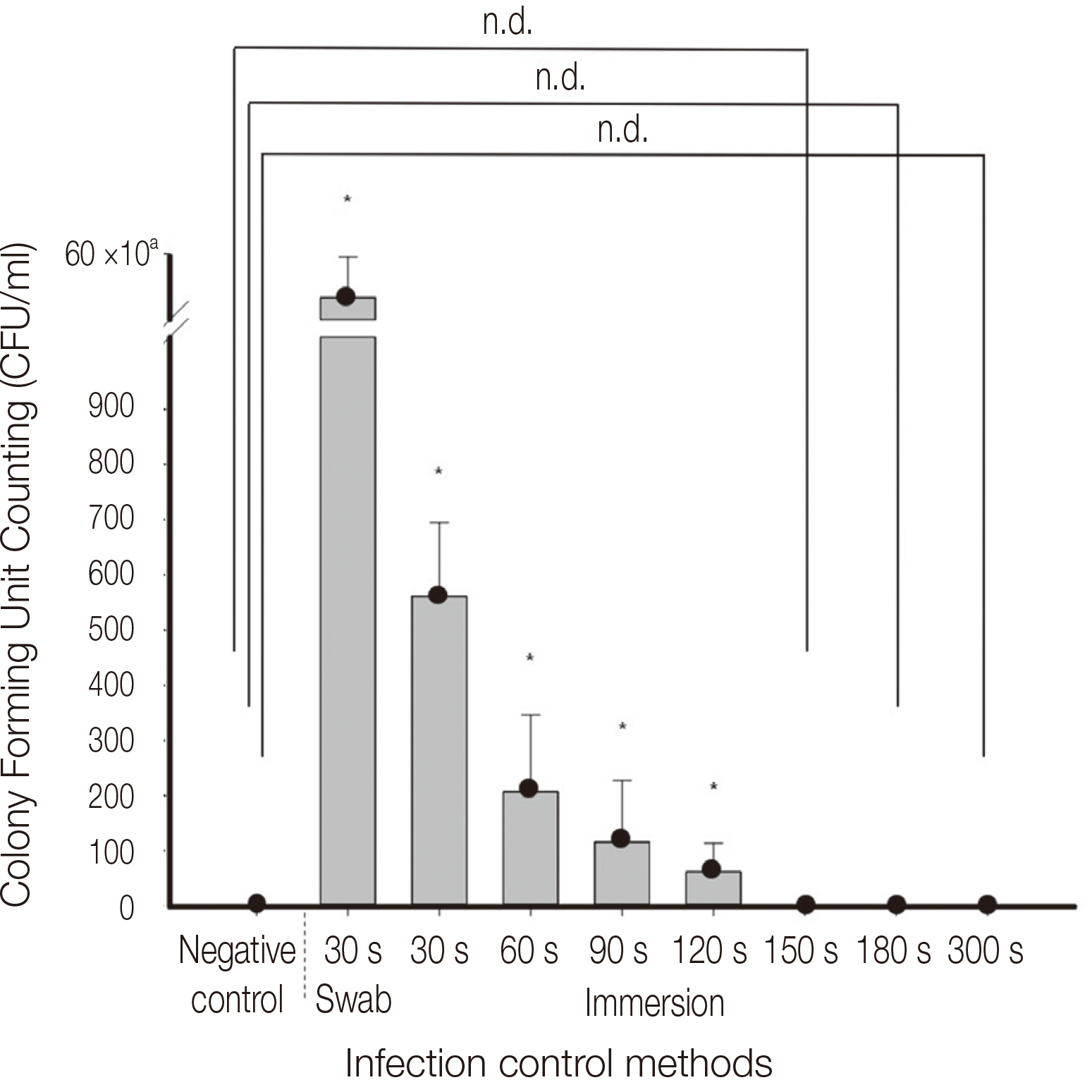

Results

The number of colony forming units and optical density analysis showed a statistically significant difference compared to the positive control. On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference between the negative control and the group immersed in the 83% ethanol solution for more than 150 seconds.

Conclusion

It is recommended to use the ethanol solution as a pre-cleaning process before sterilization, since the intermediatelevel disinfection method using ethanol solution alone for the infection control of the dental implant hand driver cannot clinically secure the sterility.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Verran J, Kossar S, McCord JF. 1996; Microbiological study of selected risk areas in dental technology laboratories. J Dent. 24:77–80. DOI: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)00052-6,. PMID: 8636497.2. Younai FS. 2010; Health care-associated transmission of hepatitis B & C viruses in dental care (dentistry). Clin Liver Dis. 14:93–104.3. American Dental Association Council (ADA). 1988; Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. Council on Dental Materials, Instruments, and Equipment. Council on Dental Practice. Council on Dental Therapeutics. J Am Dent Assoc. 116:241–8. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.1988.0341,. PMID: 3422675.4. Connor C. 1991; Cross-contamination control in prosthodontic practice. Int J Prosthodont. 4:337–44. PMID: 1811627.5. Shaw FE Jr, Barrett CL, Hamm R, Peare RB, Coleman PJ, Hadler SC, Fields HA, Maynard JE. 1986; Lethal outbreak of hepatits B in dental practice. JAMA. 255:3260–4.6. Robinson P, Challacombe S. 1993; Transmission of HIV in a dental practice - the facts. Br Dent J. 175:383–4. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808331. PMID: 8257651.7. Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. 2003; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for infection control in dental health care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 52:1–61. PMID: 14685139.8. Korea Center for Disease Control & Prevention (KCDC). Guideline for prevention and control of Healthcare associated infections. http://is.cdc.go.kr/upload_comm/refile.do?cmd=fileDownloadC&comfile_se=tr7LGqXmG||^||H||^||4gNkq9Xs1FbTVBXw3qniQFmLDPUCWeg=&comfile_fs=20190716155652731519727&comfile_fn=%EC%9D%98%EB%A3%8C%EA%B4%80%EB%A0%A8%EA%B0%90%EC%97%BC+%ED%91%9C%EC%A4%80%EC%98%88%EB%B0%A9%EC%A7%80%EC%B9%A8%EC%84%9C%28%EC%9B%B9%EC%9A%A9-%EC%88%98%EC%A0%95-20190712%29.pdf&comfile_c=www1&comfile_fd=1599701414928. updated 2020 Sep 17.9. Alapatt JG, Varghese NM, Joy PT, Saheer MK, Correya BA. 2016; Infection Control in Dental Office: A Review. IOSR-JDMS. 15:10–5.10. Abraham CM. 2014; A brief historical perspective on dental implants, their surface coatings and treatments. Open Dent J. 16:50–5. DOI: 10.2174/1874210601408010050,. PMID: 24894638. PMCID: PMC4040928.11. Straumann® Dental Implant System. Guideline for cleaning, disinfection and sterilization. https://www.straumann.com/content/dam/media-center/straumann/en/documents/brochure/technical-information/152.802-en_low.pdf. updated 2020 Sep 17.12. Rutala WA, Weber DJ. 2004; Disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities: what clinicians need to know. Clin Infect Dis. 39:702–9. DOI: 10.1086/423182,. PMID: 15356786.13. American Dental Association Council (ADA). 1996; Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. ADA Council on Scientific Affairs and ADA Council on Dental Practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 127:672–80. DOI: 10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0280,. PMID: 8642147.14. Rutala WA, Weber DJ. Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/disinfectionguidelines-H.pdf. updated 2020 Sep 4.15. Linley E, Denyer SP, McDonnell G, Simons C, Maillard JY. 2012; Use of hydrogen peroxide as a biocide: new consideration of its mechanisms of biocidal action. J Antimicrob Chemother. 67:1589–96. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dks129,. PMID: 22532463.16. Gottardi W, Debabov D, Nagl M. 2013; N-chloramines, a promising class of well-tolerated topical anti-infectives. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 57:1107–14. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.02132-12,. PMID: 23295936. PMCID: PMC3591902.17. Morton HE. 1950; The relationship of concentration and germicidal efficiency of ethyl alcohol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 53:191–6. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1950.tb31944.x. PMID: 15433175.18. Sugama J, Uchida S, Yamashiro N, Morishima Y, Hirose T, Miyazawa T, Satoh T, Satoh Y, Iinuma K, Wada Y, Tachibana M. 2004; Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide on Corrosion of Stainless Steel, (II). J Nucl Sci Technol. 41:880–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1950.tb31944.x,. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1950.tb31944.x,. PMID: 23295936. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1950.tb31944.x,.19. Oliet S, Sorin SM. 1978; Inhibition of the corrosive effect of sodium hypochlorite on carbon steel endodontic instruments. J Endod. 4:12–6. DOI: 10.1016/S0099-2399(78)80242-8,. PMID: 277625.20. You YO, Kim KJ, Min BM, Chung CP. 1999; Staphylococcus lugdunensis - a potential pathogen in oral infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 88:297–302. DOI: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70031-4. PMID: 10503857.21. Etiene J, Fleurette J, Ninet JF, Farvet P, Gauer LD. 1986; Staphylococcal endocarditis after dental extraction. Lancet. 2:511–2. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90377-6,. PMID: 2875256.22. Belibasakis GN, Charalampakis G, Bostanci N, Stadlinger B. 2015; Peri-implant infections of oral biofilm etiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 830:69–84. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90377-6,. PMID: 25366221.23. Ben-David A, Davidson CE. 2014; Estimation method for serial dilution experiments. J Microbiol Methods. 107:214–21. DOI: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.023,. PMID: 25205541.24. Wilson GS. 1922; The proportion of viable bacteria in young cultures with special reference to the technique employed in counting. J Bacteriol. 7:405–46. DOI: 10.1016/S0099-2399(78)80242-8,.25. Daalgard P, Ross T, Kamperman L, Neumeyer K, McMeekin TA. 1994; Estimation of bacterial growth rates from turbidimetric and viable count data. Int J Food Microbiol. 23:391–404. DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90165-1,. PMID: 7873339.26. Kim JH, Lee JH. 2019; The survey on the infection control of noncritical instruments used in dental treatment. J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci. 35:27–36. DOI: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90165-1,. DOI: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.08.023,.27. Lee JH. 2013; The infection control of dental impressions. J Dent Rehabil Appl Sci. 29:183–93.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- A study on the compatibility of implant drivers

- How to strengthen infection control practices in dental clinics and hospitals

- Accuracy of different electronic torque drivers: A comparative evaluation

- Considerations for Dental Implant in the Elderly

- Study on the enhancing micro-roughness of porous surfaced dental implant through anodization