The Relationships among Media Usage Regarding COVID-19, Knowledge about Infection, and Anxiety: Structural Model Analysis

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Social Welfare, Nambu University, Gwangju, Korea

- 2Gwangju Mental Health and Welfare Commission, Gwangju, Korea

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea

- KMID: 2509531

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e426

Abstract

- Background

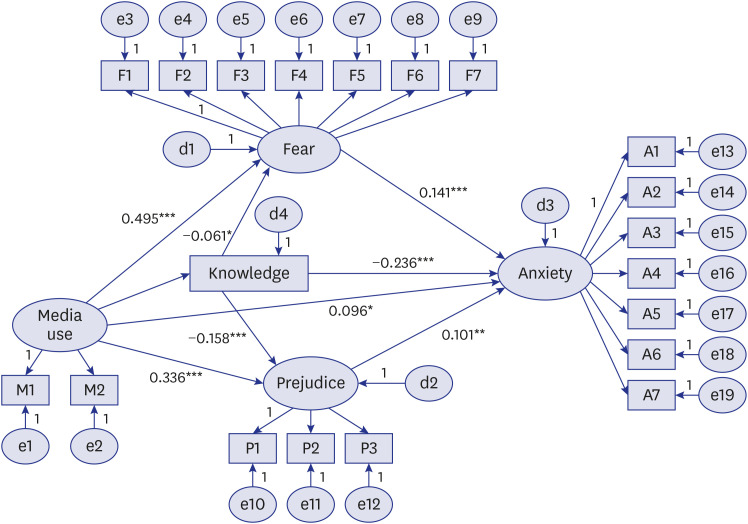

We examined the effects of mass media usage on people's level of knowledge about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), fear of infection, prejudice towards infected people, and anxiety level. In addition, we investigated whether knowledge about COVID-19 can reduce fear, prejudice, and anxiety.

Methods

We performed an anonymous online survey in 1,500 residents aged 19–65 years between April 24 and May 5 of 2020. Anxiety level was assessed using the generalized anxiety disorder-7 scale. We used a questionnaire to investigate COVID-19-related media use, knowledge about COVID-19, fear of infection, and prejudice towards infected people. We analyzed the relationships among the variables using the structural equation model.

Results

Media use had significant effects on fear of infection, prejudice against infected people, and anxiety. Knowledge about COVID-19 had a significant protective effect on fear of infection, prejudice against infected people, and anxiety. However, the effect of media use on knowledge about COVID-19 was not statistically significant. There was a partial mediating effect of prejudice against infected people and fear of infection on media usage and anxiety.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated significant effects of mass media coverage regarding COVID-19 on fear, prejudice, and anxiety. While knowledge about COVID-19 could decrease fear, prejudice, and anxiety, the use of mass media did not enhance this knowledge. Medical societies should guide mass media reporting of COVID-19 and provide appropriate public education.

Figure

Cited by 5 articles

-

Preparing for the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Vaccination: Evidence, Plans, and Implications

Jaehun Jung

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(7):e59. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e59.The Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Associated Factors among the General Public during COVID-19 Pandemic: a Cross-sectional Study in Korea

Dong Min Kim, Young Rong Bang, Joon Hee Kim, Jae Hong Park

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(29):e214. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e214.Supporting Patients With Schizophrenia in the Era of COVID-19

Sung-Wan Kim

Korean J Schizophr Res. 2021;24(2):45-51. doi: 10.16946/kjsr.2021.24.2.45.Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Adolescent Students in Daegu, Korea

Hojun Lee, Yeseul Noh, Ji Young Seo, Sang Hee Park, Myoung Haw Kim, Seunghee Won

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(46):e321. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e321.Emotional Distress of the COVID-19 Cluster Infection on Health Care Workers Working at a National Hospital in Korea

Og-Jin Jang, Young-In Chung, Jae-Woon Lee, Ho-Chan Kim, Jeong Seok Seo

J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(47):e324. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e324.

Reference

-

1. Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, Mao YP, Ye RX, Wang QZ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020; 17(9):29.

Article2. Kim SW, Su KP. Using psychoneuroimmunity against COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 2020(87):4–5.

Article3. Park SC, Park YC. Secondary emotional reactions to the COVID-19 outbreak should be identified and treated in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020; 35(17):e161. PMID: 32356422.

Article4. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020; 52:102066. PMID: 32302935.

Article5. Korean Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. Updated 2020. Accessed April 7, 2020. http://kstss.kr/?p=1370.6. Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020; 22(395):e37–8.

Article7. Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020; 49(1):1–3.8. Kim JW, Stewart R, Kang SJ, Jung SI, Kim SW, Kim JM. Telephone based interventions for psychological problems in hospital isolated patients with COVID-19. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2020; 18(4):616–620. PMID: 33124594.

Article9. Song HR, Kim WJ. Effects of risk information component of media and knowledge on risk controllability: focusing on infectious disease. Crisisonomy. 2017; 13(6):1–14.10. Kim Y. Examining social distance against the infected affected by influenza A(H1N1) news use: focusing on the stigma effect. Korean J Journal Commun Stud. 2010; 54(3):206–227.11. Dohle SC, Siegrist M. Fear and anger: antecedents and consequences of emotional response to mobile communication. J Risk Res. 2012; 15(4):435–446.12. Yang JE, Kim SJ. Cultural peculiarities and risk perception among Korean people: focusing on the mediating role of emotion and the moderating role of risk types. Crisisonomy. 2016; 12(6):143–160.13. Ju YK, You MS. Diagnostic or prognostic? analyzing the news framing of H1N1 coverage in Korea. Korean J Journal Commun Stud. 2011; 55(5):30–54.14. Yoo WH, Chung YK. The roles of interpersonal communication between exposure to mass media and MERS-preventive behavioral intentions: the moderating and mediating effects of face-to-face and online communication. Korean J Broad Tele. 2016; 30(4):121–151.15. Lee DH, Kim JY, Kang HS. The emotional distress and fear of contagion related to Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) on general public in Korea. Korean J General Psychol. 2016; 35(2):355–383.16. Park HK, Kim SH, Yang JA. The effects of exposure to MERS information and issue involvement on perceived information influence, disease prevention and information sharing. J Media Econo Cul. 2016; 14(3):7–48.

Article17. Kim M, Park IH, Kang YS, Kim H, Jhon M, Kim JW, et al. Comparison of psychosocial distress in areas with different COVID-19 prevalence in Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:593105.

Article18. Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, et al. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 2004; 170(5):793–798. PMID: 14993174.

Article19. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams BW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166(10):1092–1097. PMID: 16717171.20. Curran PJ, West SG, Finch J. The robustness of test statistics to non-normality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods. 1996; 1(1):16–29.

Article21. Hong SH. The criteria for selecting appropriate fit indices in structural equation modeling and their rationales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2000; 19(1):161–177.22. Wang Z, Gantz W. Health content in local television news. Health Commun. 2007; 21(3):213–221. PMID: 17567253.

Article23. Glik DC. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002; 28(1):33–54.

Article24. Reynolds B, Seeger MW. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J Health Commun. 2005; 10(1):43–55. PMID: 15764443.

Article25. Krewski D, Turner MC, Lemyre L, Lee EC. Expert vs. public perception of population health risks in Canada. J Risk Res. 2011; 15(6):601–625.

Article26. Herek GM, Caitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. Am J Public Health. 2003; 92(3):371–377.

Article27. Son AR, Moon JS, Shin SB, Jeon SS, Kim SR. Discriminatory attitudes towards person with HIV/AIDS (PWHAs) among adolescents in Seoul, Korea. Health Soc Sci. 2008; 23(1):31–56.28. Asmundson GJ, Taylor S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: what all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. J Anxiety Disord. 2020; 71(1):102211. PMID: 32179380.

Article29. Dong L, Bouey J. Public mental health crisis during COVID-19 pandemic, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020; 26(7):1616–1618. PMID: 32202993.

Article30. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 89:531–542. PMID: 32485289.

Article31. Jin HJ, Han DH. Interaction between message framing and consumers' prior subjective knowledge regarding food safety issues. Food Policy. 2014; 44(1):95–102.

Article32. Rousu MW, Huffman E, Shogren JE, Tegene A. Effects and value of verifiable information in a controversial market: evidence from lab auction of genetically modified foods. Econ Inq. 2007; 45(3):409–432.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- How Can the Coping Strategies Mediate the Relationship Among COVID-19 Stress, Depression, and Anxiety?

- The Effect of Fear of COVID-19 Infection and Anxiety on Loneliness: Moderated Mediation Effects of Gratitude

- Factors Affecting Compliance of Infection Control of Coronavirus Disease 2019 among Nurses Based on Health Belief Model

- Psychosocial changes in Medical Students Before and After COVID-19 Social Distancing

- Factors Influencing COVID-19 Preventive Behaviors in Nursing Students: Knowledge, Risk Perception, Anxiety, and Depression