Healthc Inform Res.

2020 Oct;26(4):335-343. 10.4258/hir.2020.26.4.335.

Determining Public Opinion of the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea and Japan: Social Network Mining on Twitter

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Health Administration, Graduate School of Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea

- 2Department of Spatial-temporal Epidemiology, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

- 3Department of Applied Statistics, Graduate School of Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea

- 4Department of Health Administration, College of Health Science, Yonsei University, Wonju, Korea

- KMID: 2508626

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2020.26.4.335

Abstract

Objectives

This study analyzed the perceptions and emotions of Korean and Japanese citizens regarding coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It examined the frequency of words used in Korean and Japanese tweets regarding COVID-19 and the corresponding changes in their interests.

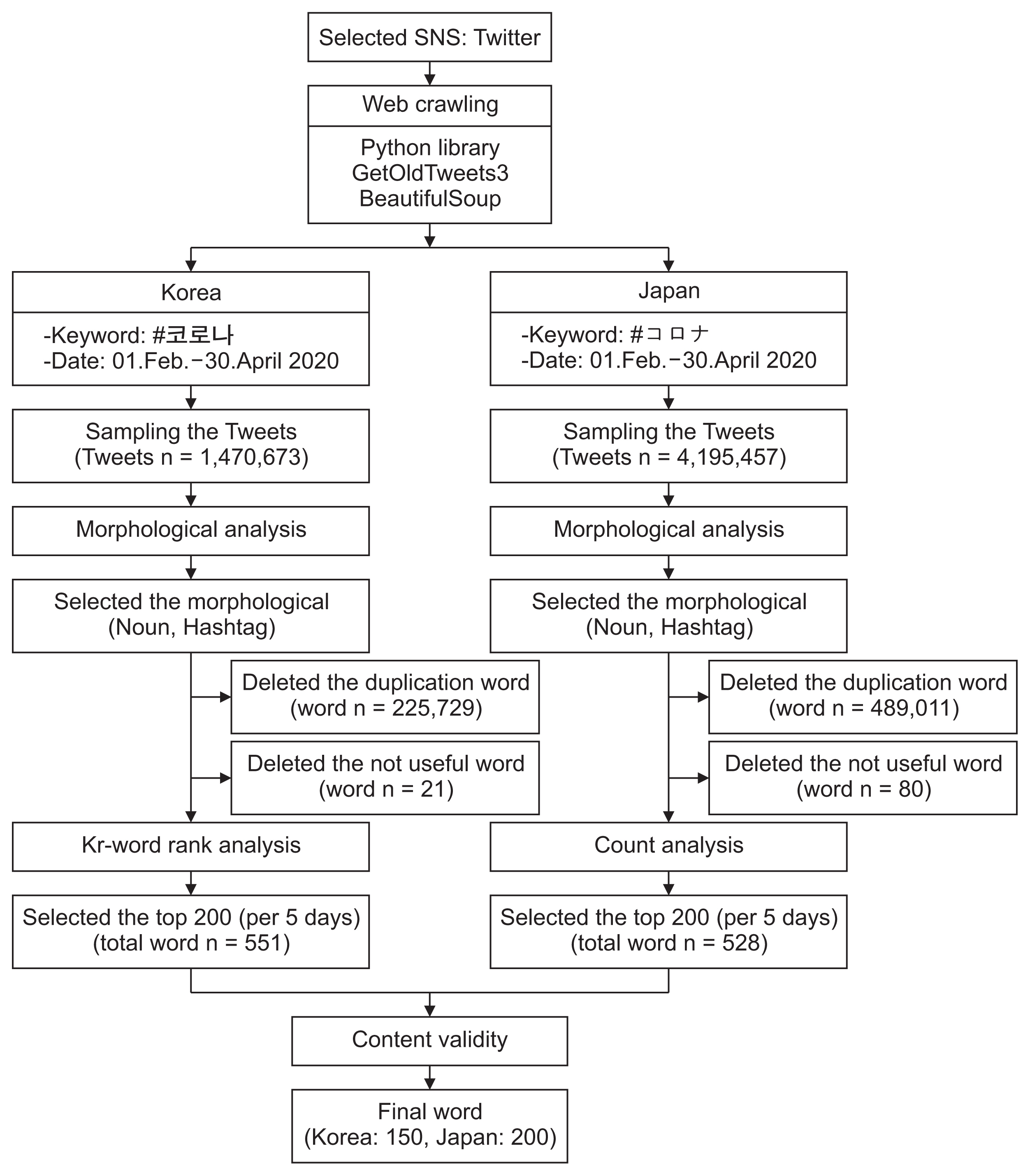

Methods

This cross-sectional study analyzed Twitter posts (Tweets) from February 1, 2020 to April 30, 2020 to determine public opinion of the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea and Japan. We collected data from Twitter (https://twitter.com/), a major social media platform in Korea and Japan. Python 3.7 Library was used for data collection. Data analysis included KR-WordRank and frequency analyses in Korea and Japan, respectively. Heat diagrams, word clouds, and rank flowcharts were also used.

Results

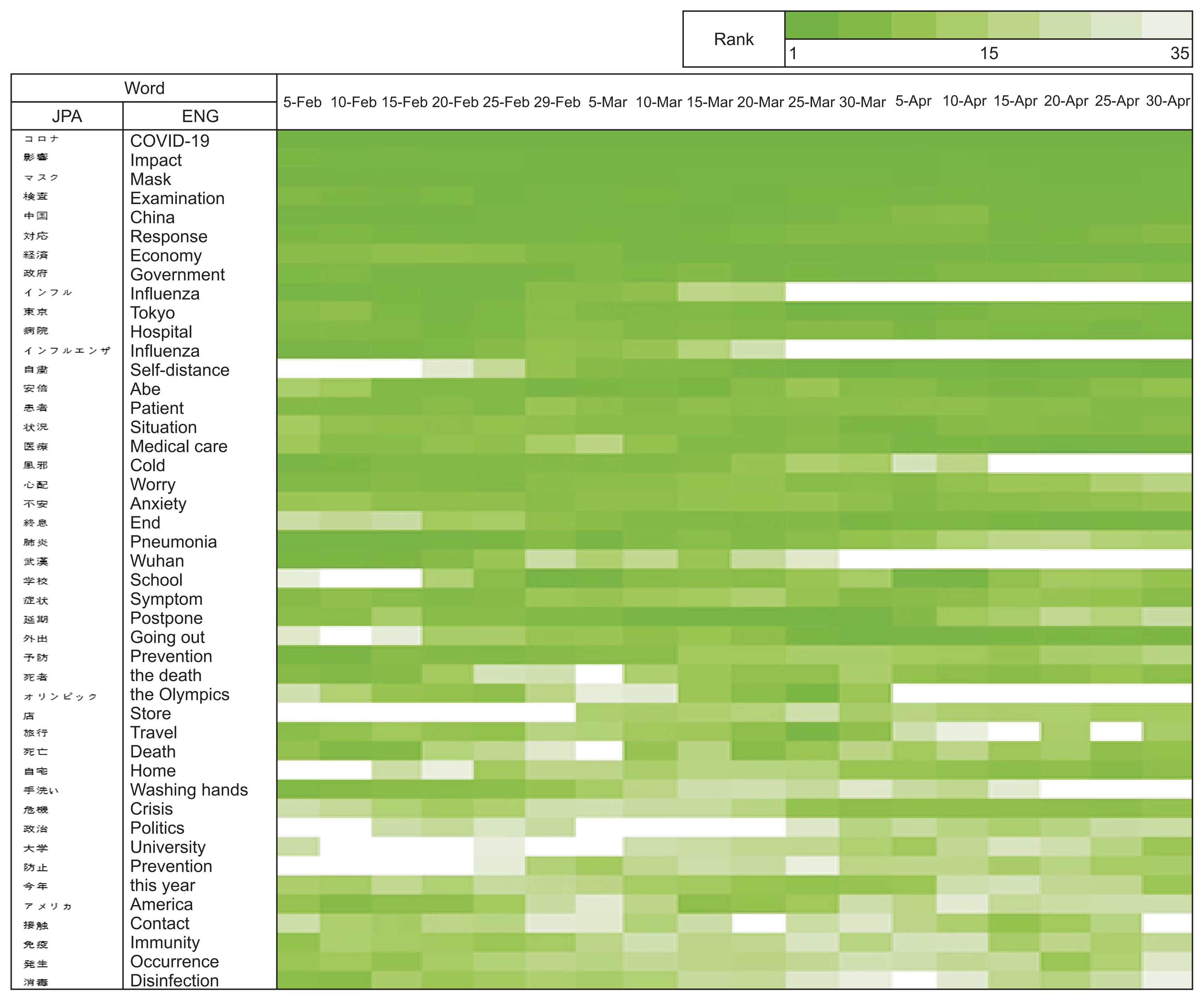

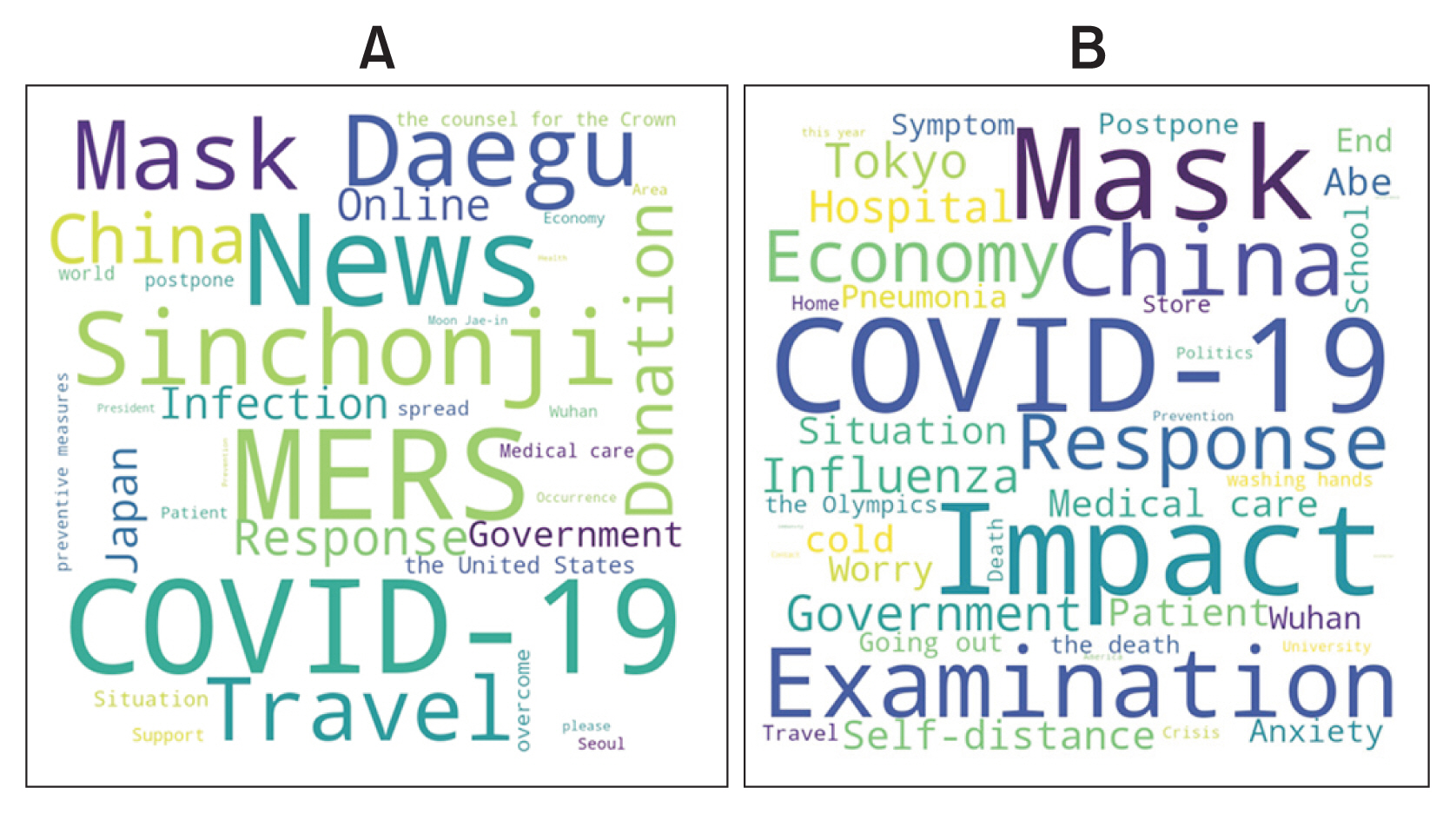

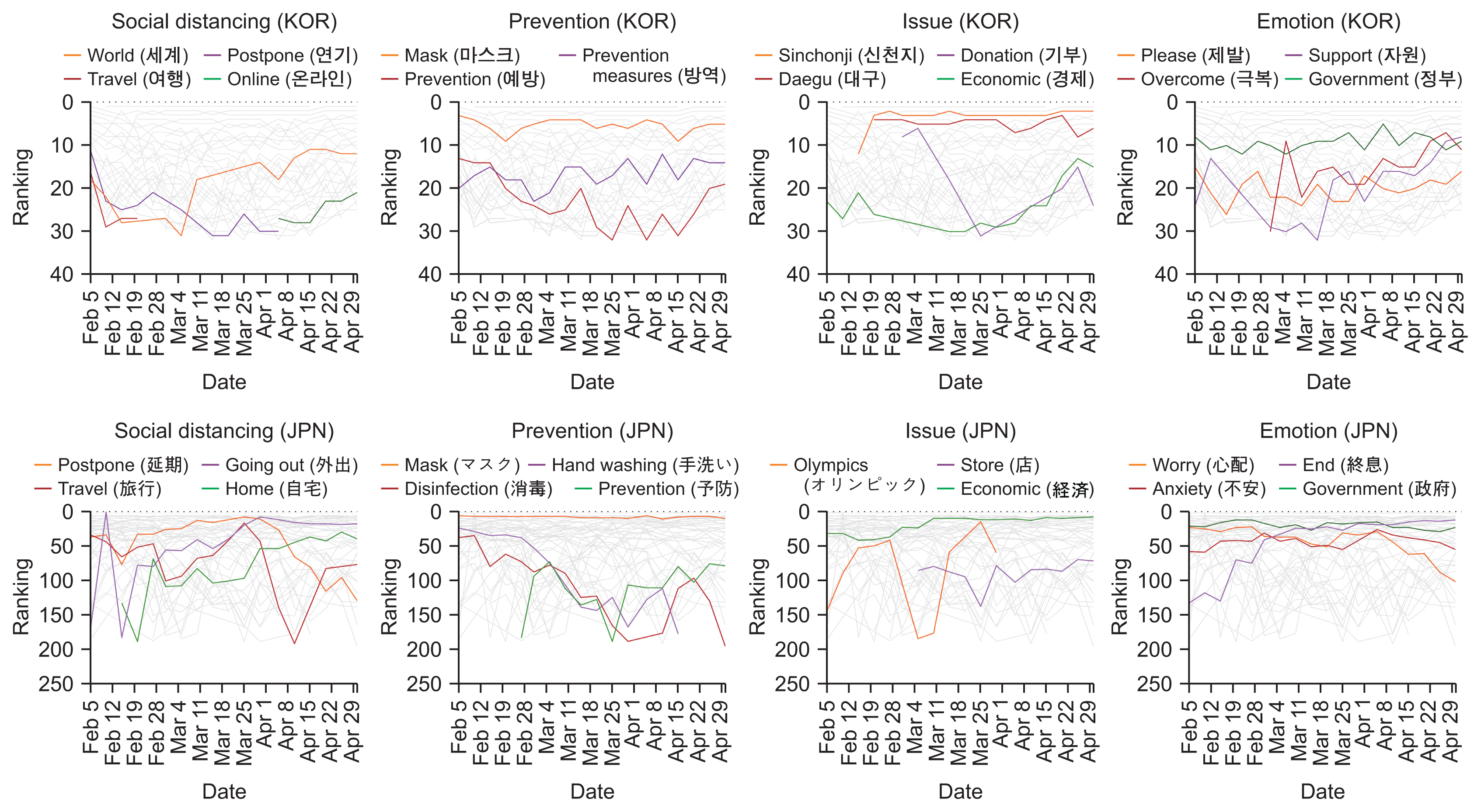

Overall, 1,470,673 and 4,195,457 tweets were collected from Korea and Japan, respectively. The word trend in Korea and Japan was analyzed every 5 days. The word cloud analysis revealed “COVID-19”, “Shinchonji”, “Mask”, “Daegu”, and “Travel” as frequently used words in Korea. While in Japan, “COVID-19”, “Mask”, “Test”, “Impact”, and “China” were identified as high-frequency words. They were divided into four categories: social distancing, prevention, issue, and emotion for the rank flowcharts. Concerning emotion, “Overcome” and “Support” increased from February in Korea, while “Worry” and “Anxiety” decreased in Japan from April 1.

Conclusions

As a result of the trend, people’s interests in the economy were high in both countries, indicating their reservations on the economic downturn. Therefore, focusing policies toward economic stability is essential. Although the interest in prevention increased since April in both countries, the general public’s relaxation regarding COVID-19 was also observed.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, Heymann DL, Ihekweazu C, Kobinger G, et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. Lancet. 2020; 395(10229):1015–8.

Article2. World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf 2020.3. Bahn GH. Coronavirus disease 2019, school closures, and children’s mental health. Soa Chongsonyon Chongsin Uihak. 2020; 31(2):74–9.4. Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020; 74(4):281–2.

Article5. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020; 52:102066.

Article6. Jacobson NC, Lekkas D, Price G, Heinz MV, Song M, O’Malley AJ, et al. Flattening the mental health curve: COVID-19 stay-at-home orders are associated with alterations in mental health search behavior in the United States. JMIR Ment Health. 2020; 7(6):e19347.

Article7. Jung SJ, Jun JY. Mental health and psychological intervention amid COVID-19 outbreak: perspectives from South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2020; 61(4):271–2.

Article8. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Implementation of mental care for new coronavirus infections [Internet]. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare;c2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://lifelinksns.net/ .9. Bartels SJ, Baggett TP, Freudenreich O, Bird BL. COVID-19 emergency reforms in Massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2020; 71(10):1078–81.

Article10. Goldman ML, Druss BG, Horvitz-Lennon M, Norquist GS, Kroeger Ptakowski K, Brinkley A, et al. Mental health policy in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatr Serv. 2020; Jun. 10. [Epub]. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000219 .

Article11. Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007; 75(5):671–82.

Article12. Hechanova R, Waelde L. The influence of culture on disaster mental health and psychosocial support interventions in Southeast Asia. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2017; 20(1):31–44.

Article13. United Nations. Policy brief: COVID-19 and the need for action on mental health. New York (NY): United Nations;2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health .14. Balabantaray RC, Mohammad M, Sharma N. Multiclass twitter emotion classification: a new approach. Int J Appl Inf Syst. 2012; 4(1):48–53.15. Chen S, Xu Y, Chang H. A simple and effective unsupervised word segmentation approach. In : Proceedings of the 25th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2011 Aug 7–11; San Francisco, CA. p. 866–71.16. Fuchs T, SchAfer F. Normalizing misogyny: hate speech and verbal abuse of female politicians on Japanese Twitter. Japan Forum. 2019; 2019:1–27.

Article17. Oh YJ. Information search ‘Naver’ overwhelming 1st place, ‘YouTube’ usage significantly increased [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: Cosmetic Insight;c2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.cosinkorea.com/mobile/article.html?no=34894 .18. The World Bank. World Bank open data (Republic of Korea, Japan) [Internet]. Washington (DC): The World Bank;c2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/?locations=KR-JP .19. Ministry of Education. Beginning of online education system for COVID-19 [Internet]. Seoul, Korea: 2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=294&boardSeq=80160&lev=0&searchType=S&statusYN=W&page=1&s=moe&m=0204&opType= .20. Ahmad T, Haroon , Baig M, Hui J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and economic impact. Pak J Med Sci. 2020; 36(COVID19-S4):S73–S78.

Article21. Statistica. Year-on-year change of weekly flight frequency of global airlines from January 6 to October 5, 2020 by country [Internet]. Hamburg, Germany: Statistica;c2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1104036/novel-coronavirus-weekly-flights-change-airlines-region/ .22. Yabe T, Tsubouchi K, Fujiwara N, Wada T, Sekimoto Y, Ukkusuri SV. Non-compulsory measures sufficiently reduced human mobility in Japan during the COVID-19 epidemic [Internet]. Ithaca (NY): arXiv.org;2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.09423 .23. Miyazawa D, Kaneko G. Face mask wearing rate predicts country’s COVID-19 death rates [Internet]. Laurel Hollow (NY): medRxiv.org;2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.22.20137745 .

Article24. NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation). “Request for leave” of each prefecture [Internet]. Tokyo, Japan: NHK;2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/special/coronavirus/tokyo/ .25. Tan W, Hao F, McIntyre RS, Jiang L, Jiang X, Zhang L, et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 87:84–92.

Article26. Kurtenbach E, Hadjicostis M. WHO warns that 1st wave of pandemic not over, immediate 2nd peak possible [Internet]. Dallas (TX): FOX4News;2020. [cited at 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.fox4news.com/news/who-warns-that-1st-wave-of-pandemic-not-over-immediate-2nd-peak-possible .

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Topic and Trends of Public Perception and Sentiments of COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea: A Text Mining Approach

- Opinion on the practice of cremation funeral for patients who died of COVID-19

- Factors Affecting Public Non-compliance With Large-scale Social Restrictions to Control COVID-19 Transmission in Greater Jakarta, Indonesia

- Emotional effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on oral surgery procedures: a social media analysis

- The COVID-19 pandemic's impact on prostate cancer screening and diagnosis in Korea