J Korean Neurosurg Soc.

2020 May;63(3):358-365. 10.3340/jkns.2020.0072.

Urological Evaluation of Tethered Cord Syndrome

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Urology, Seoul National University Children’s Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2501723

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2020.0072

Abstract

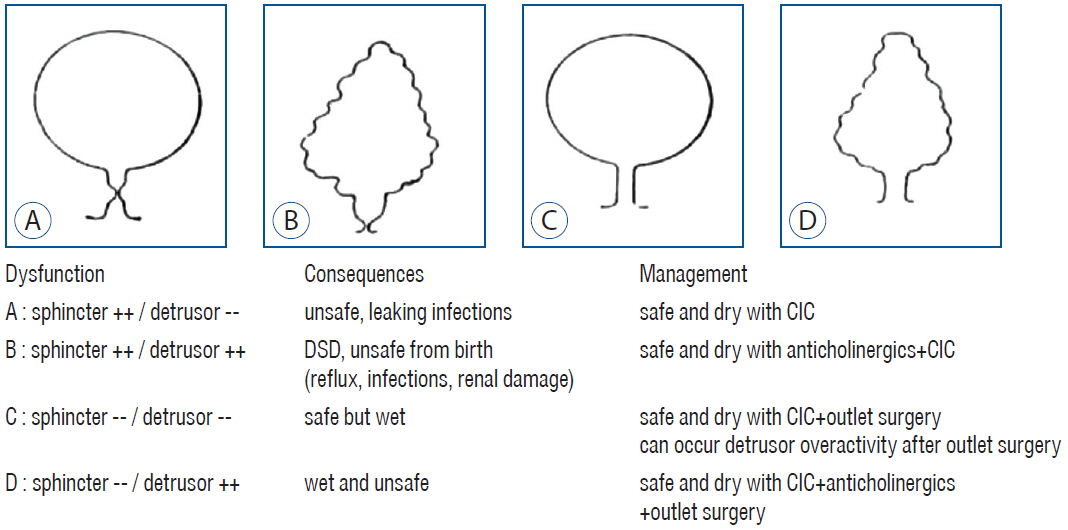

- To describe how to perform urological evaluation in children with tethered cord syndrome (TCS). Although a common manifestation of TCS is the development of neurogenic bladder in developing children, neurosurgeons often face difficulty in detecting urological problems in patients with TCS. From a urological perspective, diagnosis of TCS in developing children is further complicated due to the differentiation between neurogenic bladder dysfunctions and transient bladder dysfunctions owing to developmental problems. Due to the paucity of evidence regarding evaluation prior to and after untethering, I have shown the purpose and tools for evaluation in my own practice. This may be tailored to the types of neurogenic bladder, developmental status, and risks for deterioration. While the urodynamic study (UDS) is the gold standard test for understanding bladder function, it is not a panacea in revealing the nature of bladder dysfunction. In addition, clinicians should consider the influence of developmental processes on bladder function. Before untethering, UDS should reveal synergic urethral movement, which indicates an intact sacral reflex and lack of TCS. Postoperatively, the measurement of post-void residual urine volume is a key factor for the evaluation of spontaneous voiders. In case of elevation, fecal impaction, which is common in spinal dysraphism, should be addressed. In patients with clean intermittent catheterization, the frequency-volume chart should be monitored to assess the storage function of the bladder. Toilet training is an important sign of maturation, and its achievement should be monitored. Signs of bladder deterioration should be acknowledged, and follow-up schedule should be tailored to prevent upper urinary tract damage and also to determine an adequate timing for intervention. Neurosurgeons should be aware of urological problems related to TCS as well as urologists. Cooperation and regular discussion between the two disciplines could enhance the quality of patient care. Accumulation of experience will improve follow-up strategies.

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, Chase J, Franco I, Hoebeke P, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: Update report from the standardization committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 35:471–481. 2016.

Article2. Bauer SB, Austin PF, Rawashdeh YF, de Jong TP, Franco I, Siggard C, et al. International Children’s Continence Society’s recommendations for initial diagnostic evaluation and follow-up in congenital neuropathic bladder and bowel dysfunction in children. Neurourol Urodyn. 31:610–614. 2012.

Article3. Bauer SB, Nijman RJ, Drzewiecki BA, Sillen U, Hoebeke P; International Children’s Continence Society Standardization Subcommittee. International Children’s Continence Society standardization report on urodynamic studies of the lower urinary tract in children. Neurourol Urodyn. 34:640–647. 2015.

Article4. Chang SJ, Chiang IN, Hsieh CH, Lin CD, Yang SS. Age- and gender-specific nomograms for single and dual post-void residual urine in healthy children. Neurourol Urodyn. 32:1014–1018. 2013.

Article5. Light JK, Faganel J, Roth DR, Dimitrijevic MR. Meningomyelocele: a clinical, urodynamic and neurophysiological evaluation. J Urol. 131:717–721. 1984.

Article6. MacLellan DL. Neuromuscular dysfunction of the lower urianry tract in children. In : Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters C, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2016. 4.7. Madersbacher H. The various types of neurogenic bladder dysfunction: an update of current therapeutic concepts. Paraplegia. 28:217–229. 1990.

Article8. Stein R, Bogaert G, Dogan HS, Hoen L, Kocvara R, Nijman RJM, et al. EAU/ESPU guidelines on the management of neurogenic bladder in children and adolescent part I diagnostics and conservative treatment. Neurourol Urodyn. 39:45–57. 2020.

Article9. Verpoorten C, Buyse GM. The neurogenic bladder: medical treatment. Pediatr Nephrol. 23:717–725. 2008.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Split Cord Malformation Combined with Tethered Cord Syndrome in an Adult

- Nerve injury in an undiagnosed adult tethered cord syndrome patients following spinal anesthesia: A case report

- Tethered Cord Syndrome in Spina Bifida Occulta: A Case Report

- A Case of Enuresis and Renal Failure by Tethered Cord Syndrome with Sacral Lipoma

- Neurogenic Bladder in the Patients with Tethered Cord Syndrome: A case report