Yeungnam Univ J Med.

2020 Apr;37(2):106-111. 10.12701/yujm.2019.00402.

Predictive value of C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of meningitis in febrile infants under 3 months of age in the emergency department

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Wonkwang University School of Medicine, Iksan, Korea

- KMID: 2501417

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.12701/yujm.2019.00402

Abstract

- Background

Fever is a common cause of pediatric consultation in the emergency department. However, identifying the source of infection in many febrile infants is challenging because of insufficient presentation of signs and symptoms. Meningitis is a critical cause of fever in infants, and its diagnosis is confirmed invasively by lumbar puncture. This study aimed to evaluate potential laboratory markers for meningitis in febrile infants.

Methods

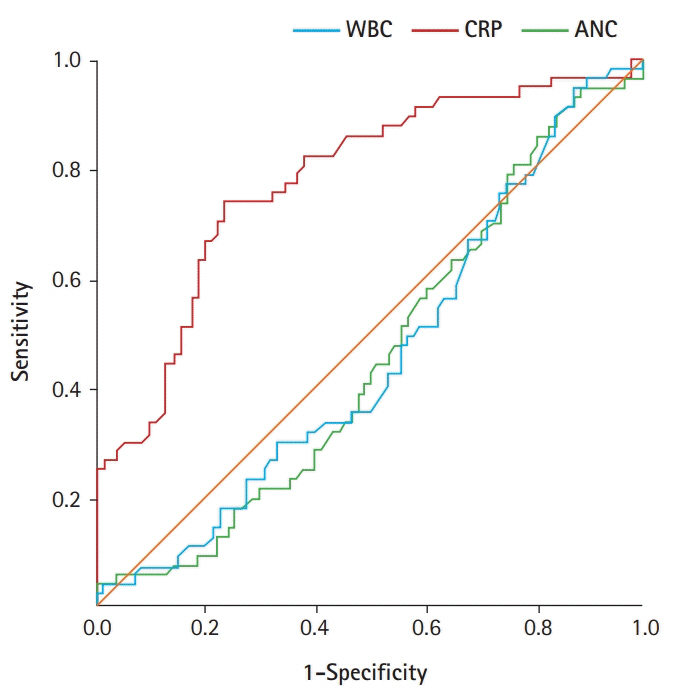

We retrospectively analyzed infants aged <3 months who visited the emergency department of our hospital between May 2012 and May 2017 because of fever of unknown etiology. Clinical information and laboratory data were evaluated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed.

Results

In total, 145 febrile infants aged <3 months who underwent lumbar punctures were evaluated retrospectively. The mean C-reactive protein (CRP) level was significantly higher in the meningitis group than in the non-meningitis group, whereas the mean white blood cell count or absolute neutrophil count (ANC) did not significantly differ between groups. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for CRP was 0.779 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.701–0.858). The AUC for the leukocyte count was 0.455 (95% CI, 0.360–0.550) and that for ANC was 0.453 (95% CI, 0.359–0.547). The CRP cut-off value of 10 mg/L was optimal for identifying possible meningitis.

Conclusion

CRP has an intrinsic predictive value for meningitis in febrile infants aged <3 months. Despite its invasiveness, a lumbar puncture may be recommended to diagnose meningitis in young, febrile infants with a CRP level >10 mg/L.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Pulliam PN, Attia MW, Cronan KM. C-reactive protein in febrile children 1 to 36 months of age with clinically undetectable serious bacterial infection. Paediatrics. 2001; 108:1275–9.

Article2. Olaciregui I, Hernandez U, Munoz JA, Emparanza JI, Landa JJ. Markers that predict serious bacterial infection in infants under 3 months of age presenting with fever of unknown origin. Arch Dis Child. 2009; 94:501–5.

Article3. Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T, Stevens R, Moll H. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systemic review. BMJ. 2011; 342:d3082.4. Bilavsky E, Yarden-Bilavsky H, Ashkenazi S, Amir J. C-reactive protein as a marker of serious bacterial infections in hospitalized febrile infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009; 98:1776–80.

Article5. Baraff LJ. Outpatient management of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1994; 330:938–9.

Article6. Dagan R, Powell KR, Hall CB, Menegus MA. Identification of infants unlikely to have serious bacterial infection although hospitalized for suspected sepsis. J Pediatr. 1985; 107:855–60.

Article7. Sturgeon JP, Zanetti B, Lindo D. C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in neonatal meningitis in England: an analysis of national variations in CRP cut-offs for lumbar puncture. BMC Pediatrics. 2018; 18:380.

Article8. Polin RA. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2012; 129:1006–15.

Article9. Jaye DL, Waites KB. Clinical applications of C-reactive protein in pediatrics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997; 16:735–46.

Article10. Du Clos TW. Function of C-reactive protein. Ann Med. 2000; 32:274–8.

Article11. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Neonatal infection (early onset): antibiotics for prevention and treatment. Clinical guideline [CG149] [Internet]. Manchester: NICE;2012. [cited 2019 Dec 14]. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg149/.12. Kelly C, Sohal A, Michael BD, Riordan A, Solomon T, Kneen R, et al. Suboptimal management of central nervous system infections in children: a multi-centre retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2012; 12:145.

Article13. Milcent K, Faesch S, Gras-Le Guen C, Dubos F, Poulalhon C, Badier I, et al. Use of procalcitonin assays to predict serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2016; 170:62–9.

Article14. Woll C, Neuman MI, Aronson PL. Management of the febrile young infant: update for the 21st century. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017; 33:748–53.15. Maniaci V, Dauber A, Weiss S, Nylen E, Becker KL, Bachur R. Procalcitonin in young febrile infants for the detection of serious bacterial infections. Pediatrics. 2008; 122:701–10.

Article16. Khilnani P, Deopujari S, Carcillo J. Recent advances in sepsis and septic shock. Indian J Pediatr. 2008; 75:821–30.

Article17. Manzano S, Bailey B, Girodias JB, Galetto-Lacour A, Cousineau J, Delvin E. Impact of procalcitonin on the management of children aged 1 to 36 months presenting with fever without source: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2010; 28:647–53.

Article18. Gajdos V, Foix L'Helias L, Mollet-Boudjemline A, Perreaux F, Trioche P, Labrune P. Factors predicting serious bacterial infections in febrile infants less than three months old: multivariate analysis. Arch Pediatr. 2005; 12:397–403.19. Schroeder S, Hochreiter M, Koehler T, Schweiger AM, Bein B, Keck FS, et al. Procalcitonin (PCT)-guided algorithm reduces length of antibiotic treatment in surgical intensive care patients with severe sepsis: results of a prospective randomized study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009; 394:221–6.

Article20. Rey C, Los Arcos M, Concha A, Medina A, Prieto S, Martinez P, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of systemic inflammatory response syndrome severity in critically ill children. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33:477–84.

Article21. Konstantinidis T, Cassimos D, Gioka T, Tsigalou C, Parasidis T, Alexandropoulou I, et al. Can procalcitonin in cerebrospinal fluid be a diagnostic tool for meningitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2015; 29:169–74.

Article22. Prasad R, Kapoor R, Mishra OP, Srivastava R, Kant Singh U. Serum procalcitonin in septic meningitis. Indian J Pediatr. 2013; 80:365–70.

Article23. Hur M, Moon HW, Yun YM, Kim KH, Kim HS, Lee KM. Comparison of diagnostic utility between procalcitonin and C-reactive protein for the patients with blood culture-positive sepsis. Korean J Lab Med. 2009; 29:529–35.

Article24. Kim EK, Lee BS, Lee JA, Jo HS, Park JD, Kim BI, et al. Clinical availability of serum procalcitonin level in the diagnosis of neonatal bacterial infection. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2001; 8:211–21.25. Kim NH, Kim JH, Lee TJ. Diagnostic value of serum procalcitonin in febrile infants under 6 months of age for the detection of bacterial infections. Korean J Pediatr Infect Dis. 2009; 16:142–9.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Predictors of Meningitis in Febrile Infants Aged 3 Months or Younger

- Risk Factors for Serious Bacterial Infection in Febrile Young Infants in a Community Referral Hospital

- Retrospective validation of the Step-by-Step approach for febrile infants younger than 90 days in the emergency department

- Usefulness of Low-Risk Criteria for Serious Bacterial Infections in Febrile Infants Younger than 90 Days of Age

- The efficacy of lumbar puncture in febrile early infants with urinary tract infection in pediatric emergency department