J Korean Med Sci.

2020 May;35(20):e133. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e133.

Seasonal Variations and Associated Factors of Gout Attacks: a Prospective Multicenter Study in Korea

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Gil Medical Center, Gachon University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

- 2Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kangwon National University School of Medicine, Chuncheon, Korea

- 3Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea

- 4Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

- 5Department of Rheumatology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

- 6Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea

- 7Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- 8Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Busan, Korea

- 9Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chung-Ang University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

- KMID: 2500843

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e133

Abstract

- Background

We purposed to evaluate the seasonality and associated factors of the incidence of gout attacks in Korea.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled patients with gout attacks who were treated at nine rheumatology clinics between January 2015 and July 2018 and followed them for 1-year. Demographic data, clinical and laboratory features, and meteorological data including seasonality were collected.

Results

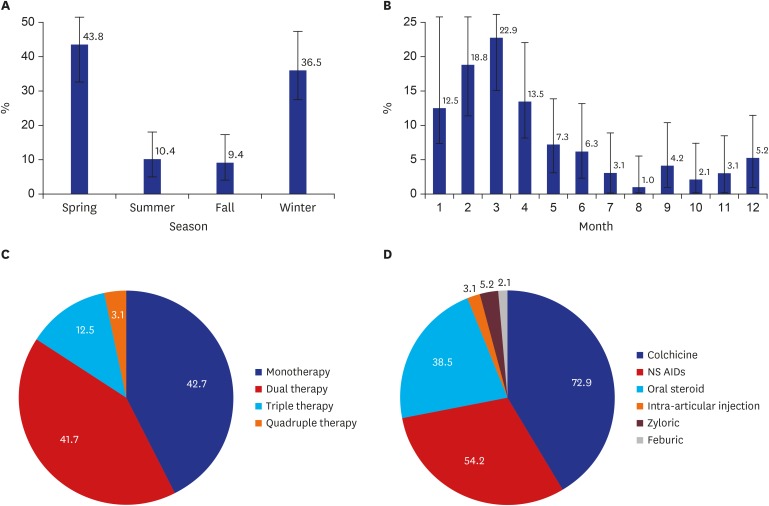

Two hundred-five patients (men, 94.1%) were enrolled. The proportion of patients with initial gout attacks was 46.8% (n = 96). The median age, body mass index, attack duration, and serum uric acid level at enrollment were 50.0 years, 25.4, 5.0 days, and 7.4 mg/dL, respectively. Gout attacks were most common during spring (43.4%, P < 0.001) and in March (23.4%, P < 0.001). A similar pattern of seasonality was observed in the group with initial gout attacks. Alcohol was the most common provoking factor (39.0%), particularly during summer (50.0%). The median diurnal temperature change on the day of the attack was highest in the spring (9.8°C), followed by winter (9.3°C), fall (8.6°C), and summer (7.1°C) (P = 0.027). The median change in humidity between the 2 consecutive days (the day before and the day of the attack) was significantly different among the seasons (3.0%, spring; 0.3%, summer; −0.9%, fall; −1.2%, winter; P = 0.015). One hundred twenty-five (61%) patients completed 1-year follow-up (51% in the initial attack group). During the follow-up period, 64 gout flares developed (21 in the initial attack group). No significant seasonal variation in the follow-up flares was found.

Conclusion

In this prospective study, the most common season and month of gout attacks in Korea are spring and March, respectively. Alcohol is the most common provoking factor, particularly during summer. Diurnal temperature changes on the day of the attack and humidity changes from the day before the attack to the day of the attack are associated with gout attack in our cohort.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

1. Robinson PC, Kempe S, Tebbutt I, Roberts L. Epidemiology of inpatient gout in Australia and New Zealand: temporal trends, comorbidities and gout flare site. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017; 20(6):779–784. PMID: 27455925.

Article2. Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M, Bonnemaire M, Malier V, Gilbert T, et al. Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008; 67(7):960–966. PMID: 17981913.

Article3. Cea Soriano L, Rothenbacher D, Choi HK, García Rodríguez LA. Contemporary epidemiology of gout in the UK general population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011; 13(2):R39. PMID: 21371293.

Article4. Xia Y, Wu Q, Wang H, Zhang S, Jiang Y, Gong T, et al. Global, regional and national burden of gout, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019; kez476. PMID: 31624843.

Article5. Choi HJ, Lee CH, Lee JH, Yoon BY, Kim HA, Suh CH, et al. Seasonality of gout in Korea: a multicenter study. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30(3):240–244. PMID: 25729244.

Article6. Schlesinger N. Acute gouty arthritis is seasonal: possible clues to understanding the pathogenesis of gouty arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005; 11(4):240–242.7. Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, Decker JL, McCarty DJ, Yü TF. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977; 20(3):895–900. PMID: 856219.

Article8. Schlesinger N, Gowin KM, Baker DG, Beutler AM, Hoffman BI, Schumacher HR Jr. Acute gouty arthritis is seasonal. J Rheumatol. 1998; 25(2):342–344. PMID: 9489831.

Article9. Arber N, Vaturi M, Schapiro JM, Jelin N, Weinberger A. Effect of weather conditions on acute gouty arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1994; 23(1):22–24. PMID: 8108663.10. Rovenský J, Mikulecký M, Masárová R. Gout and pseudogout chronobiology. J Rheumatol. 1999; 26(6):1426–1427. PMID: 10381081.11. Gallerani M, Govoni M, Mucinelli M, Bigoni M, Trotta F, Manfredini R. Seasonal variation in the onset of acute microcrystalline arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999; 38(10):1003–1006. PMID: 10534553.

Article12. Elliot AJ, Cross KW, Fleming DM. Seasonality and trends in the incidence and prevalence of gout in England and Wales 1994–2007. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009; 68(11):1728–1733. PMID: 19029167.

Article13. Park KY, Kim HJ, Ahn HS, Yim SY, Jun JB. Association between acute gouty arthritis and meteorological factors: An ecological study using a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017; 47(3):369–375. PMID: 28583691.

Article14. Choi HK, Niu J, Neogi T, Chen CA, Chaisson C, Hunter D, et al. Nocturnal risk of gout attacks. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015; 67(2):555–562. PMID: 25504842.

Article15. Neogi T, Chen C, Niu J, Chaisson C, Hunter DJ, Choi H, et al. Relation of temperature and humidity to the risk of recurrent gout attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2014; 180(4):372–377. PMID: 24993733.

Article16. Choi HK, Liu S, Curhan G. Intake of purine-rich foods, protein, and dairy products and relationship to serum levels of uric acid: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005; 52(1):283–289. PMID: 15641075.

Article17. Mak A, Ho RC, Tan JY, Teng GG, Lahiri M, Lateef A, et al. Atherogenic serum lipid profile is an independent predictor for gouty flares in patients with gouty arthropathy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009; 48(3):262–265. PMID: 19151029.

Article18. Jung JY, Choi Y, Suh CH, Yoon D, Kim HA. Effect of fenofibrate on uric acid level in patients with gout. Sci Rep. 2018; 8(1):16767. PMID: 30425304.

Article19. Walker BR, Best R, Noon JP, Watt GC, Webb DJ. Seasonal variation in glucocorticoid activity in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997; 82(12):4015–4019. PMID: 9398705.

Article20. Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, Barskova V, Becce F, Castañeda-Sanabria J, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017; 76(1):29–42. PMID: 27457514.

Article21. Sivera F, Andrés M, Carmona L, Kydd AS, Moi J, Seth R, et al. Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion of a broad panel of rheumatologists in the 3e initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014; 73(2):328–335. PMID: 23868909.

Article22. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012; 64(10):1431–1446. PMID: 23024028.

Article