Effect of Operator Volume on In-Hospital Outcomes Following Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Based on the 2014 Cohort of Korean Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (K-PCI) Registry

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiovascular, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University Medical Center, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Korea. pjs@med.yu.ac.kr

- 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea.

- 3Division of Cardiology, National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 4Heart Center, Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea.

- 5Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Regional Cardiocerebrovascular Center, Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea.

- 6Department of Internal Medicine, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 7Department of Cardiology, Myongji Hospital, Goyang, Korea.

- 8Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea.

- 9Department of Cardiology, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Korea.

- 10Division of Cardiovascular, Department of Internal Medicine, Good Morning Hospital, Pyeongtaek, Korea.

- 11Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea. drcorazon@hanmail.net

- KMID: 2468039

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0206

Abstract

- BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

The relationship between operator volume and outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has not been fully investigated. We aimed to investigate the relationship between operator PCI volume and in-hospital outcomes after primary PCI for STEMI.

METHODS

Among the total of 44,967 consecutive cases of PCI enrolled in the Korean nationwide, retrospective registry (K-PCI registry), 8,282 patients treated with PCI for STEMI by 373 operators were analyzed. PCI volumes above the 75th percentile (>30 cases/year), between the 75th and 25th percentile (10-30 cases/year), and below the 25th percentile (<10 cases/year) were defined as high, moderate, and low-volume operators, respectively. In-hospital outcomes including mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), stent thrombosis, stroke, and urgent repeat PCI were analyzed.

RESULTS

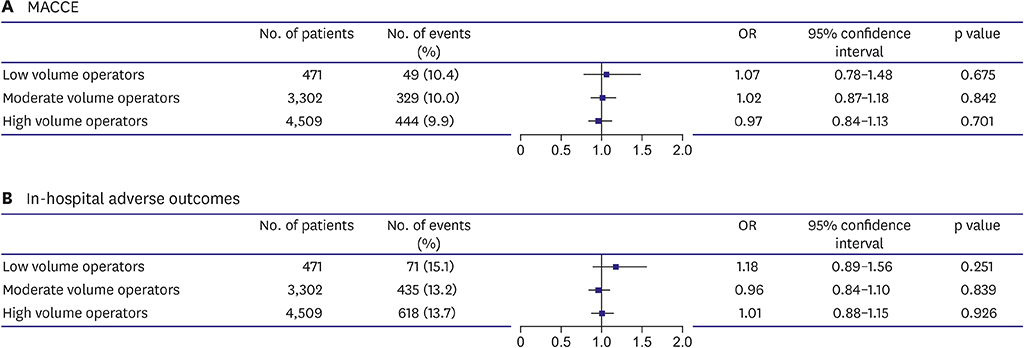

The average number of primary PCI cases performed by 373 operators was 22.2 in a year. In-hospital mortality after PCI for STEMI was 571 cases (6.9%). In-hospital outcomes by operator volume showed no significant differences in the death rate, cardiac death, non-fatal MI, and stent thrombosis. However, the rate of urgent repeat PCI tended to be lower in the high-volume operator (0.6%) than in the moderate-(0.7%)/low-(1.5%) volume operator groups (p=0.095). The adjusted odds ratios for adverse in-hospital outcomes were similar in the 3 groups. Multivariate analysis also showed that operator volume was not a predictor for adverse in-hospital outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

In-hospital outcomes after primary PCI for STEMI were not associated with operator volume in the K-PCI registry.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 3 articles

-

Impact of Hospital Volume of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) on In-Hospital Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Based on the 2014 Cohort of the Korean Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (K-PCI) Registry

Byong-Kyu Kim, Deuk-Young Nah, Kang Un Choi, Jun-Ho Bae, Moo-Yong Rhee, Jae-Sik Jang, Keon-Woong Moon, Jun-Hee Lee, Hee-Yeol Kim, Seung-Ho Kang, Woo hyuk Song, Seung Uk Lee, Byung-Ju Shim, Hangjae Chung, Min Su Hyon

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(11):1026-1036. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0172.The Operator Volume of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Does Not Guarantee Its Quality in Korea

Chang-Hwan Yoon

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(2):145-147. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2019.0389.Implementation of National Health Policy for the Prevention and Control of Cardiovascular Disease in South Korea: Regional-Local Cardio-Cerebrovascular Center and Nationwide Registry

Ju Mee Wang, Byung Ok Kim, Jang-Whan Bae, Dong-Jin Oh

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(5):383-398. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2021.0001.

Reference

-

1. Hannan EL, Wu C, Walford G, et al. Volume-outcome relationships for percutaneous coronary interventions in the stent era. Circulation. 2005; 112:1171–1179.

Article2. Moscucci M, Share D, Smith D, et al. Relationship between operator volume and adverse outcome in contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention practice: an analysis of a quality-controlled multicenter percutaneous coronary intervention clinical database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:625–632.

Article3. Badheka AO, Patel NJ, Grover P, et al. Impact of annual operator and institutional volume on percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes: a 5-year United States experience (2005–2009). Circulation. 2014; 130:1392–1406.4. Fanaroff AC, Zakroysky P, Dai D, et al. Outcomes of PCI in relation to procedural characteristics and operator volumes in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017; 69:2913–2924.5. Jang JS, Han KR, Moon KW, et al. The current status of percutaneous coronary intervention in Korea: based on year 2014 cohort of Korean percutaneous coronary intervention (K-PCI) registry. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:328–340.

Article6. Writing Committee Members. Harold JG, Bass TA, et al. ACCF/AHA/SCAI 2013 update of the clinical competence statement on coronary artery interventional procedures: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians task force on clinical competence and training (writing committee to revise the 2007 clinical competence statement on cardiac interventional procedures). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013; 82:E69–111.7. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. EuroIntervention. 2015; 10:1024–1094.

Article8. Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Yamaji K, et al. Impact of institutional and operator volume on short-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention: a report from the Japanese nationwide registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017; 10:918–927.9. Hulme W, Sperrin M, Curzen N, et al. Operator volume is not associated with mortality following percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society registry. Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:1623–1634.

Article10. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018; 39:119–177.11. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update on primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016; 67:1235–1250.12. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007; 115:2344–2351.13. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:2231–2264.

Article14. Srinivas VS, Hailpern SM, Koss E, Monrad ES, Alderman MH. Effect of physician volume on the relationship between hospital volume and mortality during primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53:574–579.

Article15. Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011; 377:1409–1420.

Article16. Zhang J, Gao X, Kan J, et al. Intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: the ULTIMATE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:3126–3137.17. Hong SJ, Kim BK, Shin DH, et al. Effect of intravascular ultrasound-guided vs angiography-guided everolimus-eluting stent implantation: the IVUS-XPL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015; 314:2155–2163.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Current Status of Coronary Intervention in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease

- Consecutive Multivessel Myocardial Infarction during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

- The Operator Volume of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Does Not Guarantee Its Quality in Korea

- Impact of Hospital Volume of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) on In-Hospital Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Based on the 2014 Cohort of the Korean Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (K-PCI) Registry

- The Prognostic Impact of Hypertriglyceridemia and Abdominal Obesity in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention