Investig Magn Reson Imaging.

2019 Sep;23(3):259-263. 10.13104/imri.2019.23.3.259.

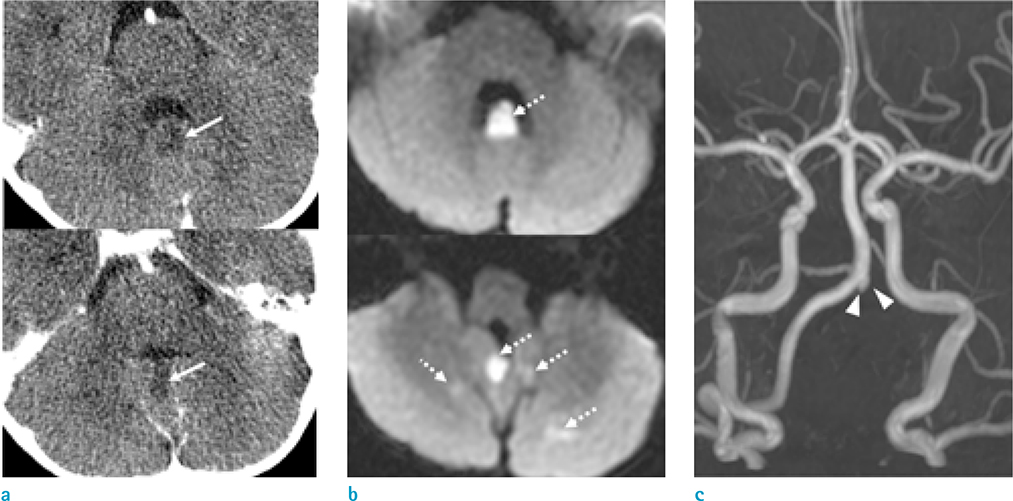

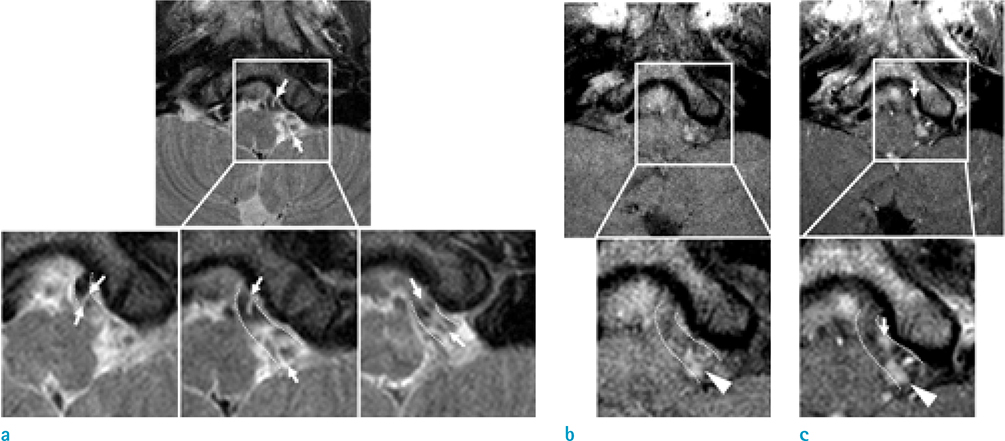

Spontaneous Intracranial Vertebral Artery Dissection in a 2-Year-Old Child Diagnosed with High-Resolution MRI: a Case Report

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Radiology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Ajou University Medical Center, Suwon, Korea. miranhanajou@gmail.com

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Ajou University Medical Center, Suwon, Korea.

- KMID: 2459880

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.13104/imri.2019.23.3.259

Abstract

- Although many imaging modalities can play some roles in the diagnosis of vertebral artery dissection (VAD), digital subtraction angiography (DSA) remains the gold standard method, with the highest detection rate and ability to assist in planning for endovascular treatment. However, this tool is often avoided in children because its invasive nature and it exposes them to radiation. High resolution magnetic resonance imaging (HR-MRI) have been suggested to be a reliable and non-invasive alternative, but it has never been discussed in children in whom vertebral artery dissection is a rare condition. In this report, we evaluate a case of a 2-year-old child who initially presented with cerebellar symptoms, and was early diagnosed with vertebral artery dissection using HR-MRI and was successfully treated.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Hasan I, Wapnick S, Tenner MS, Couldwell W. Vertebral artery dissection in children: a comprehensive review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2002; 37:168–177.

Article2. Cheon JE, Kim IO, Kim WS, Hwang YS, Wang KC, Yeon KM. MR diagnosis of cerebellar infarction due to vertebral artery dissection in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2001; 31:163–166.

Article3. Rafay MF, Armstrong D, Deveber G, Domi T, Chan A, MacGregor DL. Craniocervical arterial dissection in children: clinical and radiographic presentation and outcome. J Child Neurol. 2006; 21:8–16.

Article4. Han M, Rim NJ, Lee JS, Kim SY, Choi JW. Feasibility of high-resolution MR imaging for the diagnosis of intracranial vertebrobasilar artery dissection. Eur Radiol. 2014; 24:3017–3024.

Article5. Kaufmann TJ, Huston J 3rd, Mandrekar JN, Schleck CD, Thielen KR, Kallmes DF. Complications of diagnostic cerebral angiography: evaluation of 19,826 consecutive patients. Radiology. 2007; 243:812–819.6. Choi YJ, Jung SC, Lee DH. Vessel wall imaging of the intracranial and cervical carotid arteries. J Stroke. 2015; 17:238–255.

Article7. Habs M, Pfefferkorn T, Cyran CC, et al. Age determination of vessel wall hematoma in spontaneous cervical artery dissection: a multi-sequence 3T cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011; 13:76.

Article8. Park KJ, Jung SC, Kim HS, et al. Multi-contrast high-resolution magnetic resonance findings of spontaneous and unruptured intracranial vertebral artery dissection: qualitative and quantitative analysis according to stages. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016; 42:23–31.

Article9. Mizutani T. Natural course of intracranial arterial dissections. J Neurosurg. 2011; 114:1037–1044.

Article10. Tan MA, Armstrong D, MacGregor DL, Kirton A. Late complications of vertebral artery dissection in children: pseudoaneurysm, thrombosis, and recurrent stroke. J Child Neurol. 2009; 24:354–360.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- High-Resolution Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Intracranial Vertebral Artery Dissecting Aneurysm for Planning of Endovascular Treatment

- Chirotherapy Associated Vertebral Artery Dissection: Case Illustration and Literature Review

- Spontaneous Resolution of Dissecting Aneurysm of the Vertebral Artery

- A Case of Bilateral Spontaneous Extracranial Vertebral Artery Dissection

- Diagnosis and Management of the Spontaneous Intracranial Vertebral Artery Dissection