Risk Factor Management for Atrial Fibrillation

- Affiliations

-

- 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. cby6908@yuhs.ac

- KMID: 2455785

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0212

Abstract

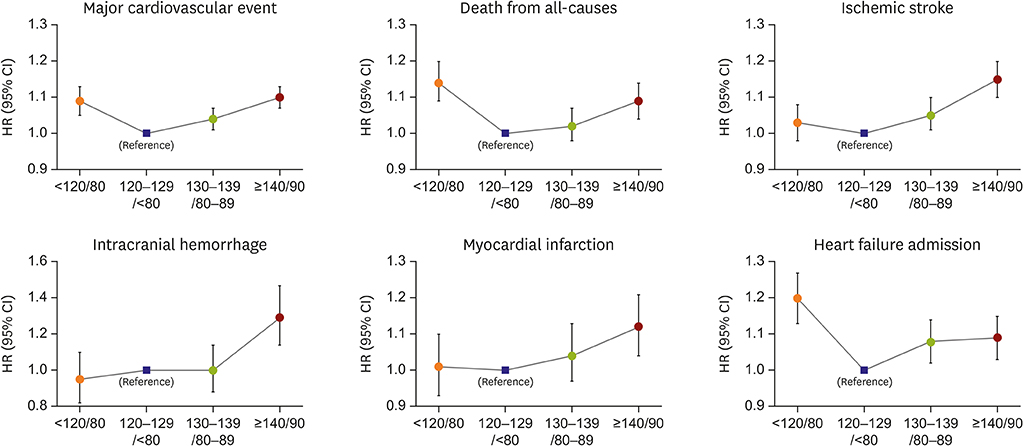

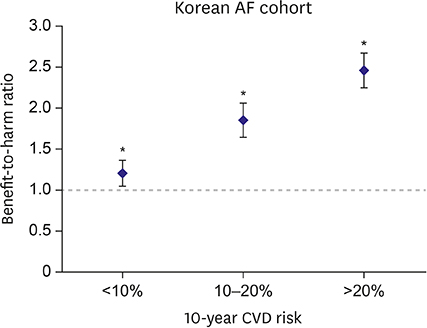

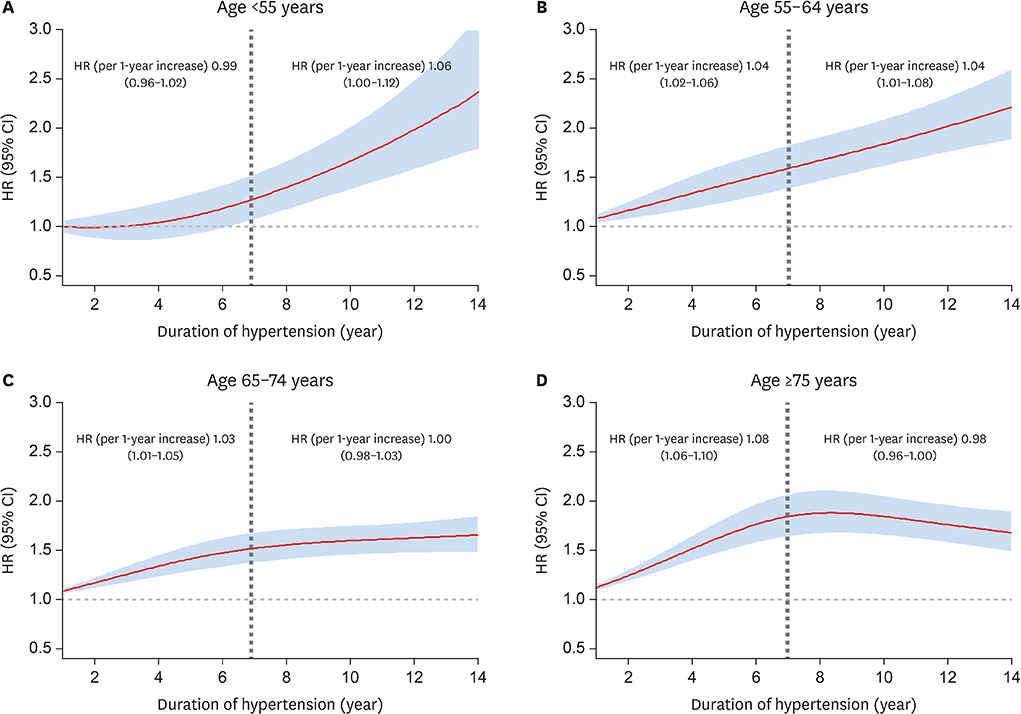

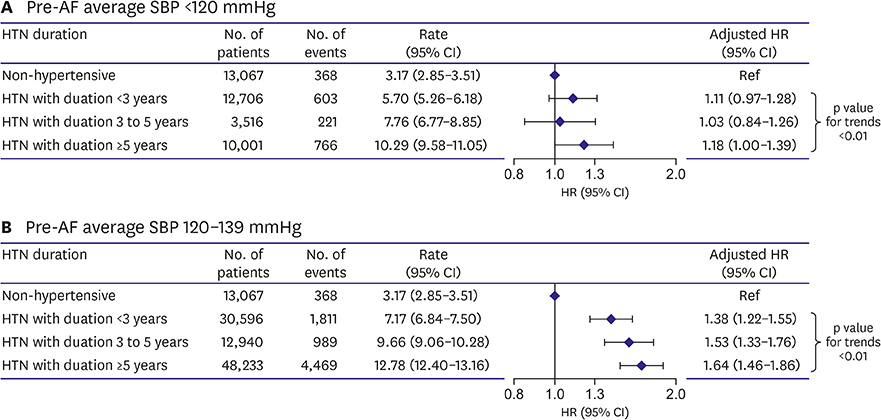

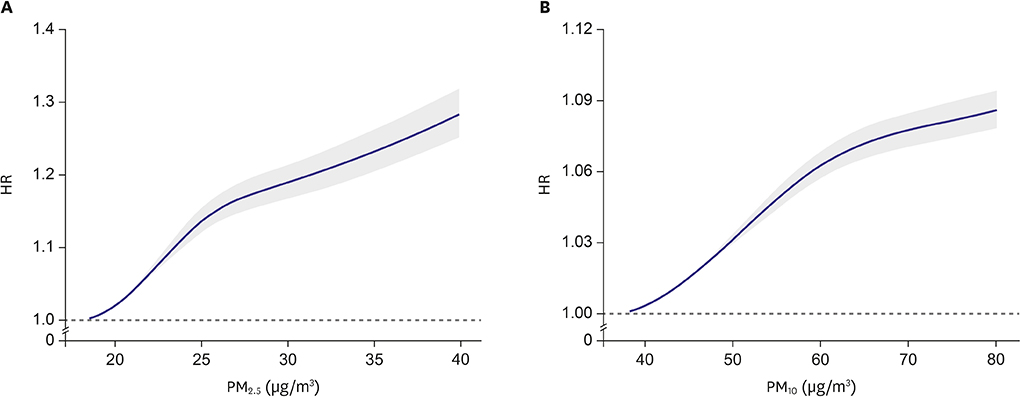

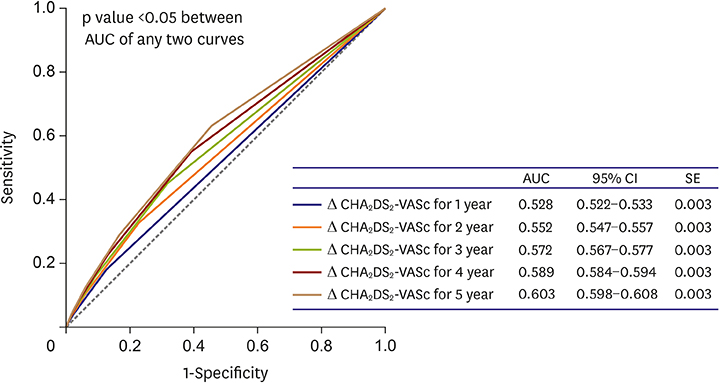

- Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia in the general population. Many cardiovascular diseases and concomitant conditions increase the risk of the development of AF, recurrent AF, and AF-associated complications. Knowledge of these factors and their management is hence important for the optimal management of patients with AF. Recent studies have suggested that lowering the blood pressure threshold can improve the patients' outcome. Moreover, adverse events associated with a longer duration of hypertension can be prevented through strict blood pressure control. Pre-hypertension, impaired fasting glucose, abdominal obesity, weight fluctuation, and exposure to air pollution are related to the development of AF. Finally, female sex is not a risk factor of stroke, and the age threshold for stroke prevention should be lowered in Asian populations. The management of diseases related to AF should be provided continuously, whereas lifestyle factors should be monitored in an integrated manner.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Cited by 5 articles

-

Increased Hb Levels Are Associated with the Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation: But Is It Related to the Occurrence of Stroke?

Junbeom Park

Korean Circ J. 2020;50(12):1111-1112. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0495.The Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Korean Patients with Early-onset Atrial Fibrillation after Catheter Ablation

Yae Min Park, Seung Young Roh, Dae In Lee, Jaemin Shim, Jong-Il Choi, Sang Weon Park, Young-Hoon Kim

J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(49):e411. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e411.Esophageal Endoscopy after High-power and Short-duration Ablation in Atrial Fibrillation Patients

Dong Geum Shin, Hong Euy Lim

Korean Circ J. 2020;51(2):154-156. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0488.Fine Particulate Matter: a Threat to the Heart Rhythm

Jinhee Ahn

Korean Circ J. 2021;51(2):171-173. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2020.0501.Optimal Rhythm Control Strategy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation

Daehoon Kim, Pil-Sung Yang, Boyoung Joung

Korean Circ J. 2022;52(7):496-512. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2022.0078.

Reference

-

1. Lee H, Kim TH, Baek YS, et al. The trends of atrial fibrillation-related hospital visit and cost, treatment pattern and mortality in Korea: 10-year nationwide sample cohort data. Korean Circ J. 2017; 47:56–64.

Article2. Kim TH, Yang PS, Uhm JS, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >/=75 [doubled], diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack [doubled], vascular disease, age 65–74, female) for stroke in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: A Korean nationwide sample cohort study. Stroke. 2017; 48:1524–1530.3. Joung B, Lee JM, Lee KH, et al. 2018 Korean guideline of atrial fibrillation management. Korean Circ J. 2018; 48:1033–1080.

Article4. Kim D, Yang PS, Yu HT, et al. Risk of dementia in stroke-free patients diagnosed with atrial fibrillation: data from a population-based cohort. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:2313–2323.

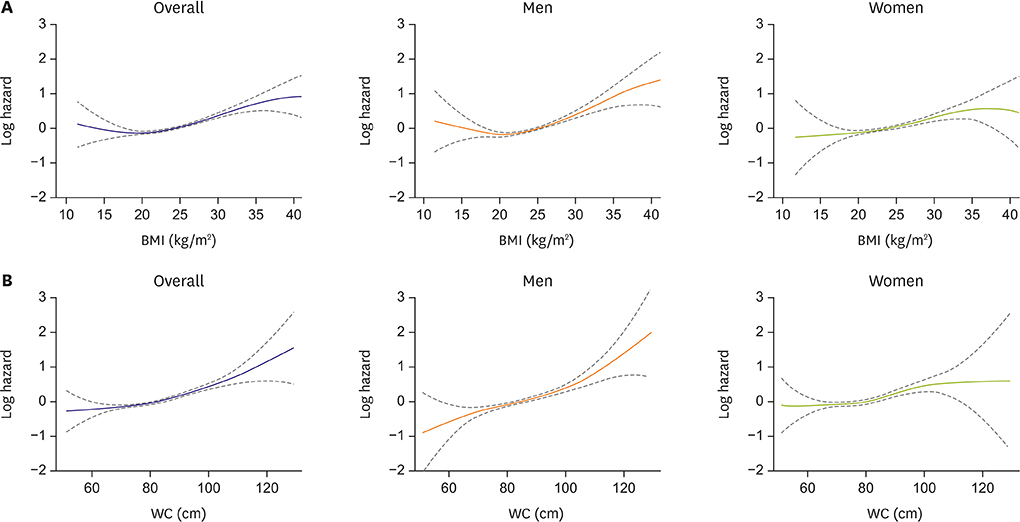

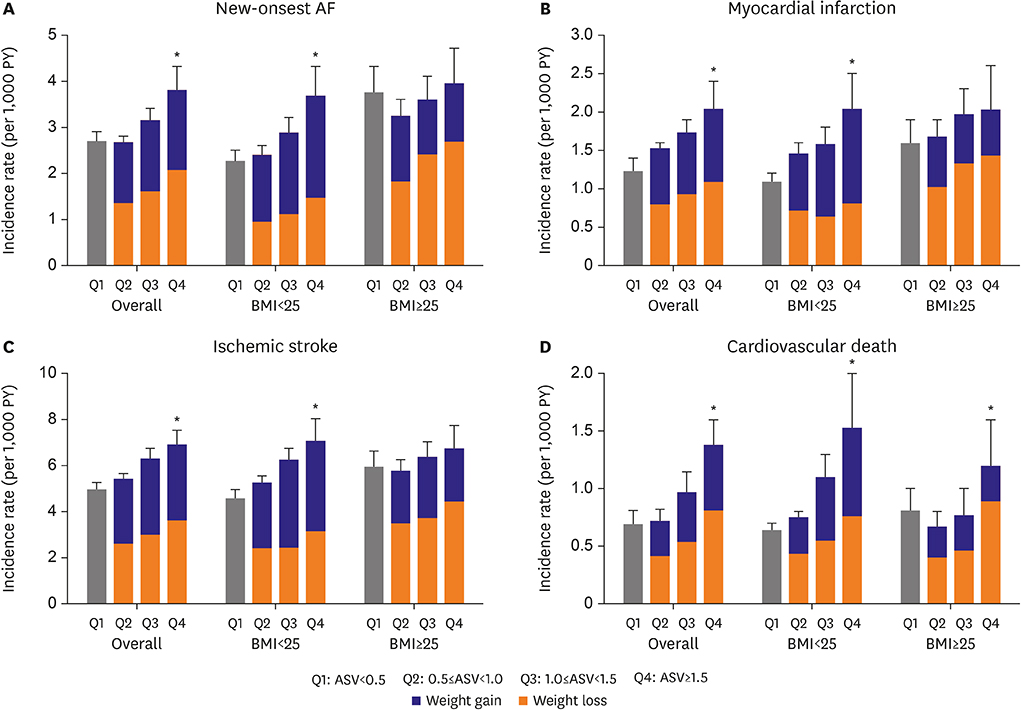

Article5. Lim YM, Yang PS, Jang E, et al. Body mass index variability and long-term risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation in the general population: a Korean nationwide cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019; 94:225–235.

Article6. Mazurek M, Shantsila E, Lane DA, Wolff A, Proietti M, Lip GY. Guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment improves outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the community-based Darlington atrial fibrillation registry. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017; 92:1203–1213.7. Lip GY. The ABC pathway: an integrated approach to improve AF management. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017; 14:627–628.

Article8. Kim TH, Yang PS, Kim D, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc score for identifying truly low-risk atrial fibrillation for stroke: a Korean nationwide cohort study. Stroke. 2017; 48:2984–2990.9. Kim D, Yang PS, Kim TH, et al. Ideal blood pressure in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 72:1233–1245.

Article10. Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P, et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet. 2015; 386:154–162.

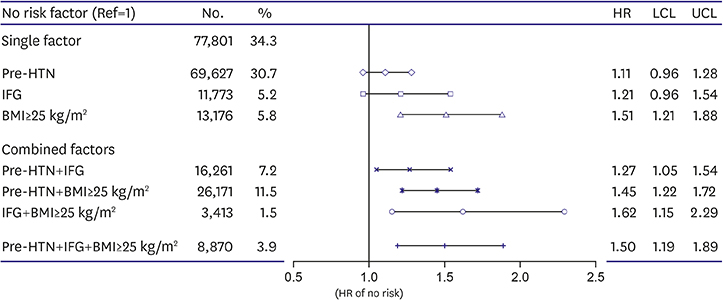

Article11. Lee SS, Kong KA, Kim D, et al. Clinical implication of an impaired fasting glucose and prehypertension related to new onset atrial fibrillation in a healthy Asian population without underlying disease: a nationwide cohort study in Korea. Eur Heart J. 2017; 38:2599–2607.

Article12. Manolis AJ, Rosei EA, Coca A, et al. Hypertension and atrial fibrillation: diagnostic approach, prevention and treatment. Position paper of the Working Group ‘Hypertension Arrhythmias and Thrombosis’ of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2012; 30:239–252.13. Kim TH, Yang PS, Yu HT, et al. Effect of hypertension duration and blood pressure level on ischaemic stroke risk in atrial fibrillation: nationwide data covering the entire Korean population. Eur Heart J. 2019; 40:809–819.

Article14. Yoon M, Yang PS, Jang E, et al. Dynamic changes of CHA2DS2-VASc score and the risk of ischaemic stroke in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2018; 118:1296–1304.15. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:2893–2962.16. Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, et al. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004; 292:2471–2477.

Article17. Tedrow UB, Conen D, Ridker PM, et al. The long- and short-term impact of elevated body mass index on the risk of new atrial fibrillation the WHS (Women's Health Study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55:2319–2327.18. Abed HS, Samuel CS, Lau DH, et al. Obesity results in progressive atrial structural and electrical remodeling: implications for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2013; 10:90–100.

Article19. Baek YS, Yang PS, Kim TH, et al. Associations of abdominal obesity and new-onset atrial fibrillation in the general population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017; 6:e004705.

Article20. Frost L, Benjamin EJ, Fenger-Grøn M, Pedersen A, Tjønneland A, Overvad K. Body fat, body fat distribution, lean body mass and atrial fibrillation and flutter. A Danish cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014; 22:1546–1552.

Article21. Britton KA, Massaro JM, Murabito JM, Kreger BE, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Body fat distribution, incident cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:921–925.

Article22. Huxley RR, Misialek JR, Agarwal SK, et al. Physical activity, obesity, weight change, and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014; 7:620–625.23. Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, et al. Long-term effect of goal-directed weight management in an atrial fibrillation cohort: a long-term follow-up study (legacy). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 65:2159–2169.24. Pedersen OD, Abildstrøm SZ, Ottesen MM, et al. Increased risk of sudden and non-sudden cardiovascular death in patients with atrial fibrillation/flutter following acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006; 27:290–295.

Article25. Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, et al. C-reactive protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001; 104:2886–2891.26. Malouf JF, Kanagala R, Al Atawi FO, et al. High sensitivity C-reactive protein: a novel predictor for recurrence of atrial fibrillation after successful cardioversion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 46:1284–1287.27. Hwang HJ, Ha JW, Joung B, et al. Relation of inflammation and left atrial remodeling in atrial fibrillation occurring in early phase of acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011; 146:28–31.

Article28. Soliman EZ, Safford MM, Muntner P, et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014; 174:107–114.

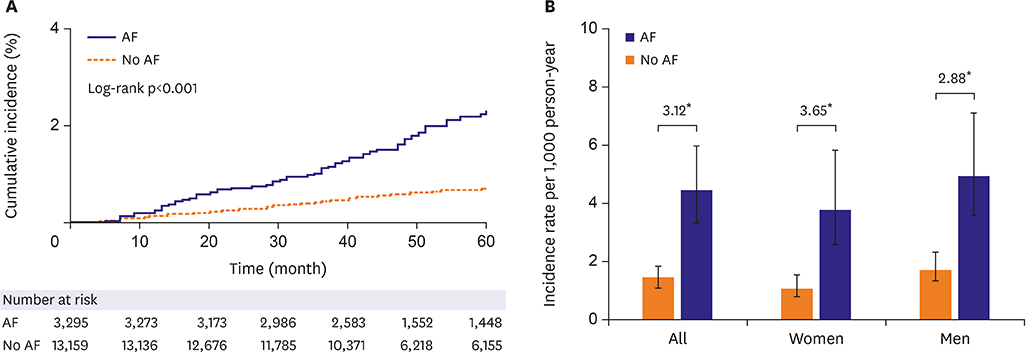

Article29. Lee HY, Yang PS, Kim TH, et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction: a nation-wide propensity-matched study. Sci Rep. 2017; 7:12716.

Article30. Peters A, Dockery DW, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001; 103:2810–2815.

Article31. Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA 3rd, et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010; 121:2331–2378.32. Kim IS, Sohn J, Lee SJ, et al. Association of air pollution with increased incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias recorded by implantable cardioverter defibrillators: vulnerable patients to air pollution. Int J Cardiol. 2017; 240:214–220.

Article33. Sohn J, You SC, Cho J, Choi YJ, Joung B, Kim C. Susceptibility to ambient particulate matter on emergency care utilization for ischemic heart disease in Seoul, Korea. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016; 23:19432–19439.

Article34. Link MS, Luttmann-Gibson H, Schwartz J, et al. Acute exposure to air pollution triggers atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:816–825.

Article35. Kim IS, Yang PS, Lee J, et al. Long-term exposure of fine particulate matter air pollution and incident atrial fibrillation in the general population: a nationwide cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2019; 283:178–183.

Article36. Lip G, Freedman B, De Caterina R, Potpara TS. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: past, present and future. Comparing the guidelines and practical decision-making. Thromb Haemost. 2017; 117:1230–1239.37. Kang SH, Choi EK, Han KD, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation not receiving oral anticoagulants - Korean nationwide population-based study -. Circ J. 2017; 81:1158–1164.38. Friberg L, Benson L, Rosenqvist M, Lip GY. Assessment of female sex as a risk factor in atrial fibrillation in Sweden: nationwide retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012; 344:e3522.

Article39. Mikkelsen AP, Lindhardsen J, Lip GY, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C, Olesen JB. Female sex as a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012; 10:1745–1751.

Article40. Nielsen PB, Skjøth F, Overvad TF, Larsen TB, Lip GY. Female sex is a risk modifier rather than a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation: should we use a CHA2DS2-VA score rather than CHA2DS2-VASc? Circulation. 2018; 137:832–840.41. Chao TF, Liu CJ, Wang KL, et al. Should atrial fibrillation patients with 1 additional risk factor of the CHA2DS2-VASc score (beyond sex) receive oral anticoagulation? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 65:635–642.42. Olesen JB, Lip GY, Hansen ML, et al. Validation of risk stratification schemes for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2011; 342:d124.

Article43. Kim TH, Yang PS, Yu HT, et al. Age threshold for ischemic stroke risk in atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2018; 49:1872–1879.

Article44. Siu CW, Lip GY, Lam KF, Tse HF. Risk of stroke and intracranial hemorrhage in 9727 Chinese with atrial fibrillation in Hong Kong. Heart Rhythm. 2014; 11:1401–1408.

Article45. Guo Y, Apostolakis S, Blann AD, et al. Validation of contemporary stroke and bleeding risk stratification scores in non-anticoagulated Chinese patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2013; 168:904–909.

Article46. Chao TF, Lip GY, Liu CJ, et al. Validation of a modified CHA2DS2-VASc score for stroke risk stratification in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study. Stroke. 2016; 47:2462–2469.47. Lip GY, Wang KL, Chiang CE. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) for stroke prevention in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: time for a reappraisal. Int J Cardiol. 2015; 180:246–254.

Article48. Chao TF, Wang KL, Liu CJ, et al. Age threshold for increased stroke risk among patients with atrial fibrillation: a nationwide cohort study from Taiwan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 66:1339–1347.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Pharmacological Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

- Relation between Atrial Fibrillation and Echocardiographic Size of Left Atrium

- Non-medication Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

- Guideline of atrial fibrillation management

- The Mechanism of and Preventive Therapy for Stroke in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation