Anesth Pain Med.

2019 Apr;14(2):165-171. 10.17085/apm.2019.14.2.165.

Antibacterial effect of lidocaine in various clinical conditions

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea. yydshin@naver.com

- KMID: 2447964

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.17085/apm.2019.14.2.165

Abstract

- BACKGROUND

Infection, one of the complications associated with procedures, can cause fatal outcomes for patients. Although the local anesthetic agent we use is less susceptible to infection due to its antibacterial action, we performed this study to check the change in the antibacterial effect of lidocaine in various clinical conditions.

METHODS

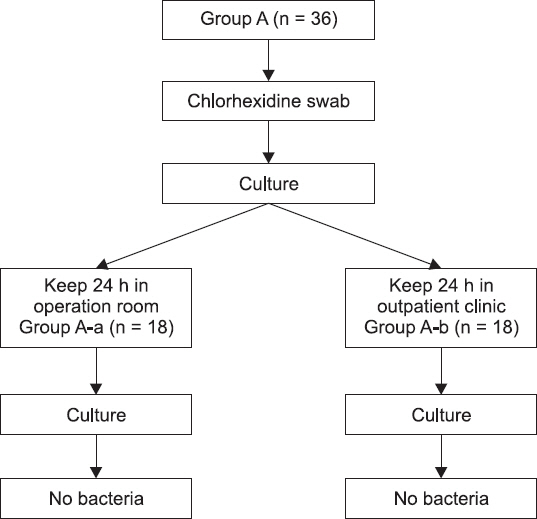

After exposing lidocaine to five contaminated environments, we checked on whether the bacteria could be cultured in blood agar plate (BAP) media. In each contaminated environment, lidocaine was exposed for 4 h (n = 9) and 8 h (n = 9), and the results were compared. Lidocaine was swabbed with chlorhexidine (group A), brought into contact with saliva (group B), skin (group C), an operating room floor and an outpatient room floor (group D), operating room air for 24 h (group A-a), and outpatient room air for 24 h (group A-b). After exposure, the culture was initiated.

RESULTS

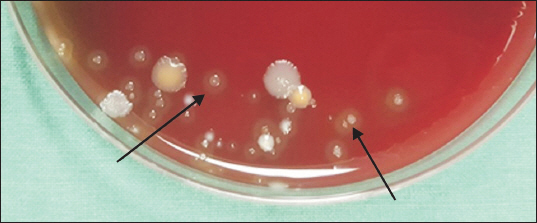

In 2 of 9 BAP media where lidocaine was exposed to saliva (group B) for 8 h, growth of a colony was observed. In gram staining, it was found to be Streptococcus viridans. No bacteria were found in any other groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Though lidocaine has strong antibacterial activity, it has been found that long-term exposure to a contaminated environment reduces its antibacterial activity and that drug contamination can be heavily affected not only by environmental but also human effects. Therefore, the use of aseptic drugs is necessary, and stopping the reuse of the drug is a way to prevent complications, including infection.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Johnson SM, Saint John BE, Dine AP. Local anesthetics as antimicrobial agents: a review. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2008; 9:205–13. DOI: 10.1089/sur.2007.036. PMID: 18426354.2. Adler DMT, Damborg P, Verwilghen DR. The antimicrobial activity of bupivacaine, lidocaine and mepivacaine against equine pathogens: an investigation of 40 bacterial isolates. Vet J. 2017; 223:27–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.05.001. PMID: 28671067.3. Lee SJ, Choi EJ, Nahm FS. Spondylodiscitis after cervical nucleoplasty without any abnormal laboratory findings. Korean J Pain. 2013; 26:181–5. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.181. PMID: 23614083. PMCID: PMC3629348.4. Kim DH, Kim HS. Epidural and psoas abscesses recognized after paravertebral trigger point injection: a case report. Korean J Pain. 2007; 20:74–7. DOI: 10.3344/kjp.2007.20.1.74.5. Begec Z, Gulhas N, Toprak HI, Yetkin G, Kuzucu C, Ersoy MO. Comparison of the antibacterial activity of lidocaine 1% versus alkalinized lidocaine in vitro. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2007; 68:242–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2007.08.007. PMID: 24683214. PMCID: PMC3967346.6. Liu K, Ye L, Sun W, Hao L, Luo Y, Chen J. Does use of lidocaine affect culture of synovial fluid obtained to diagnose periprosthetic joint infection (PJI)? Med Sci Monit. 2018; 24:448–52. DOI: 10.12659/MSM.908585. PMID: 29360804. PMCID: PMC5791422.7. Lu CW, Lin TY, Shieh JS, Wang MJ, Chiu KM. Antimicrobial effect of continuous lidocaine infusion in a Staphylococcus aureus-induced wound infection in a mouse model. Ann Plast Surg. 2014; 73:598–601. DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318276d8e7. PMID: 25310128.8. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004. 32:470–85. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.10.001.9. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, et al. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007; 122:160–6. DOI: 10.1177/003335490712200205. PMID: 17357358. PMCID: PMC1820440.10. Gosden PE, MacGowan AP, Bannister GC. Importance of air quality and related factors in the prevention of infection in orthopaedic implant surgery. J Hosp Infect. 1998; 39:173–80. DOI: 10.1016/S0195-6701(98)90255-9.11. Whyte W, Hodgson R, Tinkler J. The importance of airborne bacterial contamination of wounds. J Hosp Infect. 1982; 3:123–35. DOI: 10.1016/0195-6701(82)90004-4.12. Dharan S, Pittet D. Environmental controls in operating theatres. J Hosp Infect. 2002; 51:79–84. DOI: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1217. PMID: 12090793.13. Reynolds F. Infection as a complication of neuraxial blockade. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2005; 14:183–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2005.04.001. PMID: 15993773.14. Grewal S, Hocking G, Wildsmith JA. Epidural abscesses. Br J Anaesth. 2006; 96:292–302. DOI: 10.1093/bja/ael006. PMID: 16431882.15. Hebl JR, Niesen AD. Infectious complications of regional anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011; 24:573–80. DOI: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834a9252. PMID: 21822135.16. Nicolotti D, Iotti E, Fanelli G, Compagnone C. Perineural catheter infection: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Anesth. 2016; 35:123–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.07.025. PMID: 27871508.17. Kaufman CA, Malani AN. Fungal infections associated with contaminated steroid injections. Emerging infections 10. Scheld WM, Hughes JM, Whitley RJ, editors. Washington, DC: ASM Press;2016. p. 359–74. DOI: 10.1128/microbiolspec.EI10-0005-2015. PMID: 27227303.18. Jung SY, Kim BG, Kwon D, Park JH, Youn SK, Jeon S, et al. An outbreak of joint and cutaneous infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria after corticosteroid injection. Int J Infect Dis. 2015; 36:62–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.05.018. PMID: 26026822.19. Song JY, Sohn JW, Jeong HW, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ, Kim MJ. An outbreak of post-acupuncture cutaneous infection due to Myco- bacterium abscessus. BMC Infect Dis. 2006; 6:6. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-6. PMID: 16412228. PMCID: PMC1361796.20. Mimoz O, Lucet JC, Kerforne T, Pascal J, Souweine B, Goudet V, et al. Skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone iodine-alcohol, with and without skin scrubbing, for prevention of intravascular-catheter-related infection (CLEAN): an open- label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, two-by-two factorial trial. Lancet. 2015; 386:2069–77. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00244-5. PMID: 26388532.21. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, Carrick MM, et al. Chlorhexidine–alcohol versus povidone–iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:18–26. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810988. PMID: 20054046.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Antibacterial Effect of Lidocaine, Thrombin, and Epinephrine

- Intravenous lidocaine for the treatment of acute pain in the emergency department

- Effect of tracheal lidocaine on intubating conditions during propofol-remifentanil target-controlled infusion without neuromuscular blockade in day-case anesthesia

- Effect of Lidocaine on Pain Caused by Intravenous Injection of Diazepam ( Valium )

- A Study on The Antibacterial Effect of antibiotic Impregnated Bone Cement