J Korean Med Sci.

2017 Aug;32(8):1295-1303. 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1295.

Comparison of Follow-up Courses after Discharge from Neonatal Intensive Care Unit between Very Low Birth Weight Infants with and without Home Oxygen

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Pediatrics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. yschang@skku.edu

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea.

- KMID: 2439464

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.8.1295

Abstract

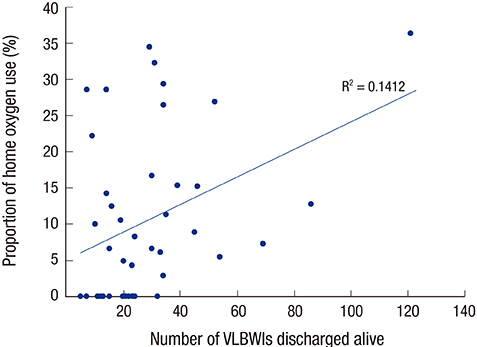

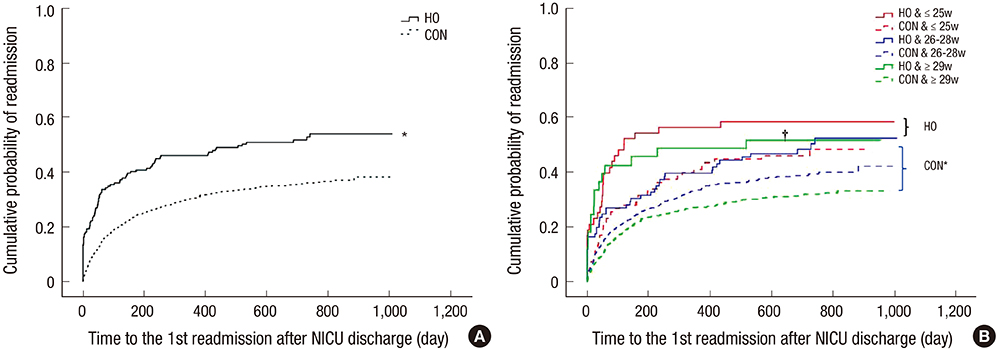

- In order to investigate the clinical impact of home oxygen use for care of premature infants, we compared the follow-up courses after neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) discharge between very low birth weight infants (VLBWIs) with and without home oxygen. We retrospectively identified 1,232 VLBWIs born at 22 to 32 weeks of gestation, discharged from the NICU of 43 hospitals in Korea between April 2009 and March 2010, and followed them up until April 2011. Clinical outcomes, medical service uses, and readmission and death rates during follow-up after the NICU discharge were compared between VLBWIs with (HO, n = 167) and those without (CON, n = 1,056) home oxygen at discharge. The HO infants comprised 13.7% of the total VLBWIs with significant institutional variations and showed a lower gestational age (GA) and birth weight than the CON infants. The HO infants had more frequent regular pediatric outpatient clinic visits (12.7 ± 7.5 vs. 9.5 ± 6.6; P < 0.010) and emergency center visits related to respiratory problems (2.5 ± 2.2 vs. 1.8 ± 1.4; P < 0.010) than the CON infants. The HO infants also had significantly increased readmission (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.25-2.04) and death risks (adjusted HR, 7.40; 95% CI, 2.06-26.50) during up to 2 years following the NICU discharge. These increased readmission and death risks in the HO infants were not related to their prematurity degree. In conclusion, home oxygen use after discharge increases the risks for healthcare utilization, readmission, and death after NICU discharge in VLBWIs, regardless of GA, requiring more careful health care monitoring during their follow-up.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Wilson-Costello D, Friedman H, Minich N, Fanaroff AA, Hack M. Improved survival rates with increased neurodevelopmental disability for extremely low birth weight infants in the 1990s. Pediatrics. 2005; 115:997–1003.2. Petrou S, Sach T, Davidson L. The long-term costs of preterm birth and low birth weight: results of a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2001; 27:97–115.3. Ralser E, Mueller W, Haberland C, Fink FM, Gutenberger KH, Strobl R, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U. Rehospitalization in the first 2 years of life in children born preterm. Acta Paediatr. 2012; 101:e1–e5.4. Underwood MA, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM. Cost, causes and rates of rehospitalization of preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2007; 27:614–619.5. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008; 122:1119–1126.6. Howard-Glenn L. Transition to home: discharge planning for the oxygen-dependent infant with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1992; 6:85–94.7. Allen J, Zwerdling R, Ehrenkranz R, Gaultier C, Geggel R, Greenough A, Kleinman R, Klijanowicz A, Martinez F, Ozdemir A, et al. Statement on the care of the child with chronic lung disease of infancy and childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 168:356–396.8. Greenough A, Alexander J, Burgess S, Bytham J, Chetcuti PA, Hagan J, Lenney W, Melville S, Shaw NJ, Boorman J, et al. Preschool healthcare utilisation related to home oxygen status. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2006; 91:F337–F341.9. Sauve RS, McMillan DD, Mitchell I, Creighton D, Hindle NW, Young L. Home oxygen therapy. Outcome of infants discharged from NICU on continuous treatment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1989; 28:113–118.10. Lee JH, Chang YS; Committee on Data Collection and Statistical Analysis, the Korean Society of Neonatology. Use of medical resources by preterm infants born at less than 33 weeks’ gestation following discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2015; 30:Suppl 1. S95–S103.11. Lodha A, Zhu Q, Lee SK, Shah PS; Canadian Neonatal Network. Neonatal outcomes of preterm infants in breech presentation according to mode of birth in Canadian NICUs. Postgrad Med J. 2011; 87:175–179.12. Fenton TR. A new growth chart for preterm babies: Babson and Benda's chart updated with recent data and a new format. BMC Pediatr. 2003; 3:13.13. Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978; 92:529–534.14. Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986; 33:179–201.15. Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 163:1723–1729.16. Saletti A, Stick S, Doherty D, Simmer K. Home oxygen therapy after preterm birth in Western Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004; 40:519–523.17. Lagatta J, Clark R, Spitzer A. Clinical predictors and institutional variation in home oxygen use in preterm infants. J Pediatr. 2012; 160:232–238.18. Hennessy EM, Bracewell MA, Wood N, Wolke D, Costeloe K, Gibson A, Marlow N; EPICure Study Group. Respiratory health in pre-school and school age children following extremely preterm birth. Arch Dis Child. 2008; 93:1037–1043.19. Peter C, Boberski B, Bohnhorst B, Pirr S. Prescription of home oxygen therapy to very low birth weight infants in Germany: a nationwide survey. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014; 53:726–732.20. Liebowitz MC, Clyman RI. Predicting the need for home oxygen therapy in preterm infants born before 28 weeks' gestation. Am J Perinatol. 2016; 33:34–39.21. Merritt TA, Pillers D, Prows SL. Early NICU discharge of very low birth weight infants: a critical review and analysis. Semin Neonatol. 2003; 8:95–115.22. Carraro S, Filippone M, Da Dalt L, Ferraro V, Maretti M, Bressan S, El Mazloum D, Baraldi E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: the earliest and perhaps the longest lasting obstructive lung disease in humans. Early Hum Dev. 2013; 89:Suppl 3. S3–S5.23. Luu TM, Lefebvre F, Riley P, Infante-Rivard C. Continuing utilisation of specialised health services in extremely preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010; 95:F320–F325.24. Landry JS, Croitoru D, Jin Y, Schwartzman K, Benedetti A, Menzies D. Health care utilization by preterm infants with respiratory complications in Quebec. Can Respir J. 2012; 19:255–260.25. Kotecha SJ, Dunstan FD, Kotecha S. Long term respiratory outcomes of late preterm-born infants. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012; 17:77–81.26. Greenough A. Long-term respiratory consequences of premature birth at less than 32 weeks of gestation. Early Hum Dev. 2013; 89:Suppl 2. S25–S27.27. Spiegler J, Schlaud M, König IR, Teig N, Hubert M, Herting E, Göpel W; German Neonatal Network, GNN. Very low birth weight infants after discharge: what do parents describe? Early Hum Dev. 2013; 89:343–347.28. Puddu M. Home care for the high-risk newborn infant. Minerva Pediatr. 2010; 62:11–14.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Erratum: Correction of Error in Result: Comparison of Follow-up Courses after Discharge from Neonatal Intensive Care Unit between Very Low Birth Weight Infants with and without Home Oxygen

- Weight Gain Study of Very Low Birth Weight Infants in Relation to Gestational Age and Birth Weight

- Management of Premature and Low Birth Weight Infants

- The Effects of Kangaroo Care on Anxiety and Confidence and Gratification of Mothering Role in Mothers of Low Birth Weight Infants

- Death in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit