J Educ Eval Health Prof.

2018;15:28. 10.3352/jeehp.2018.15.28.

Comparison of the level of cognitive processing between case-based items and non-case-based items on the Interuniversity Progress Test of Medicine in the Netherlands

- Affiliations

-

- 1Center for Education Development and Research in Health Professions (CEDAR), Research Group LEARN, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. d.cecilio.fernandes@umcg.nl

- 2Department of Education and Research, Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen, The Netherlands.

- 3Department of Surgery, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

- 4Department of Cardiology, Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven, The Netherlands.

- 5Department of Educational Development and Research, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

- KMID: 2439283

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2018.15.28

Abstract

- PURPOSE

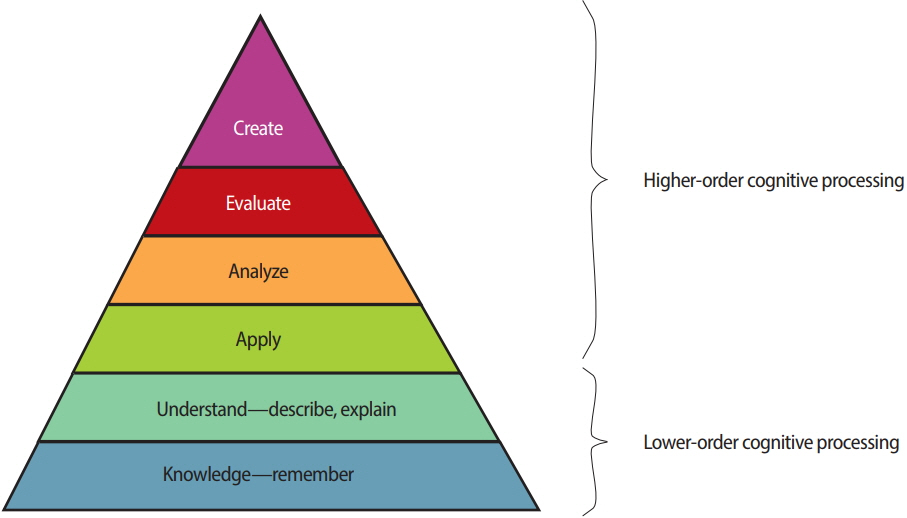

It is assumed that case-based questions require higher-order cognitive processing, whereas questions that are not case-based require lower-order cognitive processing. In this study, we investigated to what extent case-based and non-case-based questions followed this assumption based on Bloom's taxonomy.

METHODS

In this article, 4,800 questions from the Interuniversity Progress Test of Medicine were classified based on whether they were case-based and on the level of Bloom's taxonomy that they involved. Lower-order questions require students to remember or/and have a basic understanding of knowledge. Higher-order questions require students to apply, analyze, or/and evaluate. The phi coefficient was calculated to investigate the relationship between whether questions were case-based and the required level of cognitive processing.

RESULTS

Our results demonstrated that 98.1% of case-based questions required higher-level cognitive processing. Of the non-case-based questions, 33.7% required higher-level cognitive processing. The phi coefficient demonstrated a significant, but moderate correlation between the presence of a patient case in a question and its required level of cognitive processing (phi coefficient= 0.55, P< 0.001).

CONCLUSION

Medical instructors should be aware of the association between item format (case-based versus non-case-based) and the cognitive processes they elicit in order to meet the desired balance in a test, taking the learning objectives and the test difficulty into account.

Keyword

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Raupach T, Brown J, Anders S, Hasenfuss G, Harendza S. Summative assessments are more powerful drivers of student learning than resource intensive teaching formats. BMC Med. 2013; 11:61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-61.

Article2. Cilliers FJ, Schuwirth LW, Adendorff HJ, Herman N, van der Vleuten CP. The mechanism of impact of summative assessment on medical students’ learning. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010; 15:695–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-010-9232-9.

Article3. Biggs JB, Tang C. Teaching for quality learning at university: what the student does. 4th ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill: Society for Research into Higher Education, Open University Press;2011.4. Tio RA, Schutte B, Meiboom AA, Greidanus J, Dubois EA, Bremers AJ; Dutch Working Group of the Interuniversity Progress Test of Medicine. The progress test of medicine: the Dutch experience. Perspect Med Educ. 2016; 5:51–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-015-0237-1.

Article5. Wrigley W, van der Vleuten CP, Freeman A, Muijtjens A. A systemic framework for the progress test: strengths, constraints and issues: AMEE guide no. 71. Med Teach. 2012; 34:683–697. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.704437.

Article6. Cecilio-Fernandes D, Kerdijk W, Jaarsma AD, Tio RA. Development of cognitive processing and judgments of knowledge in medical students: analysis of progress test results. Med Teach. 2016; 38:1125–1129. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1170781.

Article7. Jensen JL, McDaniel MA, Woodard SM, Kummer TA. Teaching to the test… or testing to teach: exams requiring higher order thinking skills encourage greater conceptual understanding. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014; 26:307–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9248-9.

Article8. Nasstrom G. Interpretation of standards with Bloom’s revised taxonomy: a comparison of teachers and assessment experts. Int J Res Method Educ. 2009; 32:39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270902749262.

Article9. Ary D, Jacobs LC, Irvine CK, Walker DA. Introduction to research in education. 10th ed. Boston (MA): Cengage Learning;2019.10. Schuwirth LW, van der Vleuten CP. The use of progress testing. Perspect Med Educ. 2012; 1:24–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-012-0007-2.

Article11. Cecilio-Fernandes D, Cohen-Schotanus J, Tio RA. Assessment programs to enhance learning. Phys Ther Rev. 2018; 23:17–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2017.1341143.

Article12. Ripp K, Braun L. Race/ethnicity in medical education: an analysis of a question bank for step 1 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination. Teach Learn Med. 2017; 29:115–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2016.1268056.

Article13. Kushner RF, Butsch WS, Kahan S, Machineni S, Cook S, Aronne LJ. Obesity coverage on medical licensing examinations in the United States: what is being tested? Teach Learn Med. 2017; 29:123–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2016.1250641.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Investigating possible causes of bias in a progress test translation: an one-edged sword

- Analysis of Learning Objectives, Types of Question Items and Number of Question Items of a Medical College: A Case of a Medical College in Seoul

- Construction of Problem-Solving Test Items in Written Examination: Significance and Suggestions for Development

- Item development process and analysis of 50 case-based items for implementation on the Korean Nursing Licensing Examination

- Student Responses to Smart Device-Based Test on Competency Evaluation in Dental Education