J Korean Neurosurg Soc.

2019 Jan;62(1):123-129. 10.3340/jkns.2017.0282.

Superficial and Deep Skin Preparation with Povidone-Iodine for Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Surgery : A Technical Note

- Affiliations

-

- 1Victor Horsley Department of Neurosurgery, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London, UK. claudia.craven@gmail.com

- KMID: 2434354

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2017.0282

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

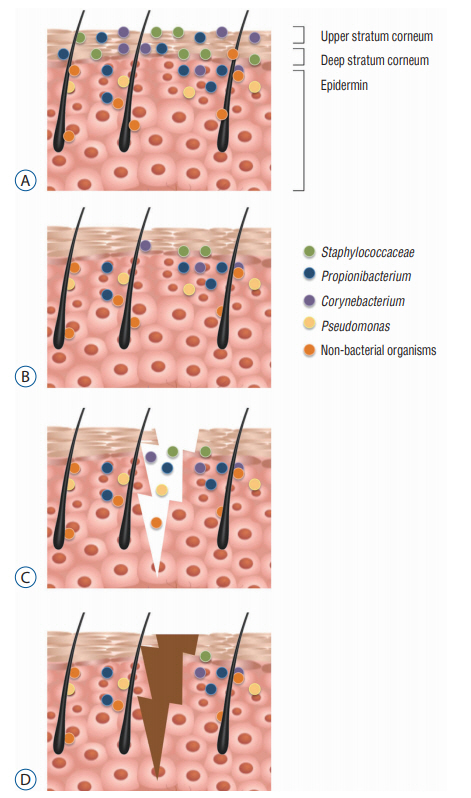

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt surgery is a common and effective treatment for hydrocephalus and cerebrospinal fluid disorders. Infection remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality after a VP shunt. There is evidence that a deep skin flora microbiome may have a role to play in post-operative infections. In this technical note, we present a skin preparation technique that addresses the issue of the skin flora beyond the initial incision.

METHODS

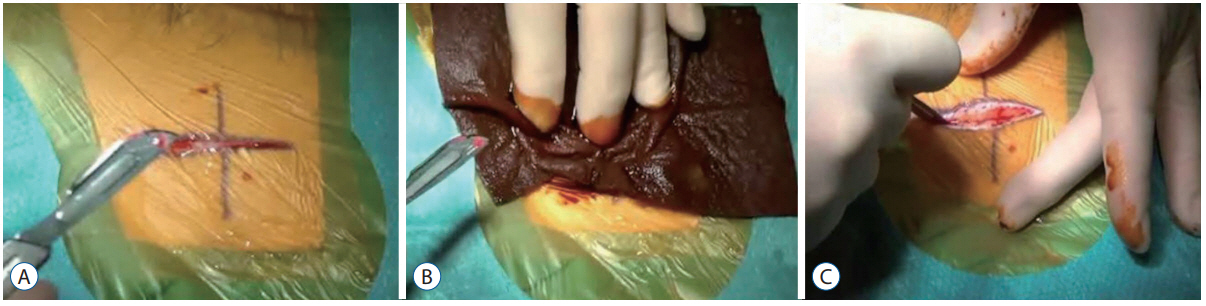

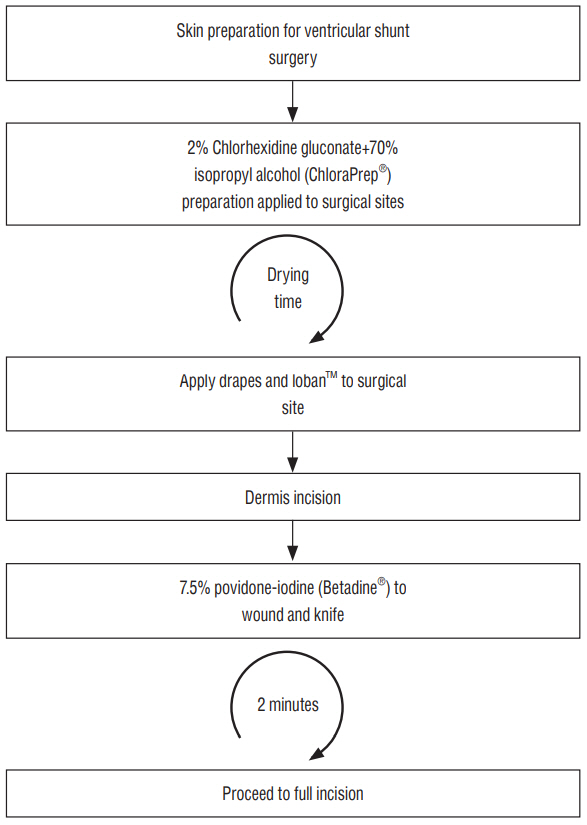

The patient is initially prepped, as standard, with. a single layer of 2% CHG+70% isopropyl alcohol. The novel stage is the "˜double incision' whereby an initial superficial incision receives a further application of povidone-iodine prior to completing the full depth incision.

RESULTS

Of the 84 shunts inserted using the double-incision method (September 2015 to September 2016), only one developed a shunt infection.

CONCLUSION

The double incision approach to skin preparation is a unique operative stage in VP shunt surgery that may have a role to play in reducing acute shunt infection.

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

References

1. Achermann Y, Goldstein EJ, Coenye T, Shirtliff ME. Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 27:419–440. 2014.

Article2. Bicknell PG. Sensorineural deafness following myringoplasty operations. J Laryngol Otol. 85:957–961. 1971.

Article3. Borgbjerg BM, Gjerris F, Albeck MJ, Borgesen SE. Risk of infection after cerebrospinal fluid shunt: an analysis of 884 first-time shunts. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 136:1–7. 1995.

Article4. Chiou CC, Wong TT, Lin HH, Hwang B, Tang RB, Wu KG, et al. Fungal infection of ventriculoperitoneal shunts in children. Clin Infect Dis. 19:1049–1053. 1994.

Article5. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, Carrick MM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-Iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 362:18–26. 2010.

Article6. Davis SE, Levy ML, McComb JG, Masri-Lavine L. Does age or other factors influence the incidence of ventriculoperitoneal shunt infections? Pediatr Neurosurg. 30:253–257. 1999.

Article7. Felbaum D, Syed HR, Snyder R, McGowan JE, Jha RT, Nair MN. Surgical adhesive drape (IO-ban) as postoperative surgical site dressing. Cureus. 7:e394. 2015.

Article8. George R, Leibrock L, Epstein M. Long-term analysis of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infections. A 25-year experience. J Neurosurg. 51:804–811. 1979.9. Gottardi W. Iodine and iodine compounds in Block SS (ed) : Disinfection, Sterilization, and Preservation. ed 6. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger;1991. p. 151–166.10. Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 324:1190–1192. 2009.

Article11. Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 9:244–253. 2011.

Article12. Grover R, Frank ME. Regional specificity of chlorhexidine effects on taste perception. Chem Senses. 33:311–318. 2008.

Article13. Gutierrez-Murgas Y, Snowden JN. Ventricular shunt infections: immunopathogenesis and clinical management. J Neuroimmunol. 276:1–8. 2014.

Article14. Hemani ML, Lepor H. Skin preparation for the prevention of surgical site infection: which agent is best? Rev Urol. 11:190–195. 2009.15. Henschen A, Olson L. Chlorhexidine-induced degeneration of adrenergic nerves. Acta Neuropathol. 63:18–23. 1984.

Article16. Jenkinson MD, Gamble C, Hartley JC, Hickey H, Hughes D, Blundell M, et al. The British antibiotic and silver-impregnated catheters for ventriculoperitoneal shunts multi-centre randomised controlled trial (the BASICS trial): study protocol. Trials. 15:4. 2014.

Article17. Kestle JR, Riva-Cambrin J, Wellons JC 3rd, Kulkarni AV, Whitehead WE, Walker ML, et al. A standardized protocol to reduce cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection: the hydrocephalus clinical research network quality improvement initiative. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 8:22–29. 2011.

Article18. Kong HH, Segre JA. Skin microbiome: looking back to move forward. J Invest Dermatol. 132(3 Pt 2):933–939. 2012.

Article19. Korinek AM, Fulla-Oller L, Boch AL, Golmard JL, Hadiji B, Puybasset L. Morbidity of ventricular cerebrospinal fluid shunt surgery in adults: an 8-year study. Neurosurgery. 68:985–994. discussion 994-985. 2011.

Article20. McClelland S 3rd, Hall WA. Postoperative central nervous system infection: incidence and associated factors in 2111 neurosurgical procedures. Clin Infect Dis. 45:55–59. 2007.

Article21. McDonnell G, Russell AD. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 12:147–179. 1999.

Article22. Nakatsuji T, Chiang HI, Jiang SB, Nagarajan H, Zengler K, Gallo RL. The microbiome extends to subepidermal compartments of normal skin. Nat Commun. 4:1431. 2013.

Article23. Pirotte BJ, Lubansu A, Bruneau M, Loqa C, Van Cutsem N, Brotchi J. Sterile surgical technique for shunt placement reduces the shunt infection rate in children: preliminary analysis of a prospective protocol in 115 consecutive procedures. Childs Nerv Syst. 23:1251–1261. 2007.

Article24. Ritz R, Roser F, Morgalla M, Dietz K, Tatagiba M, Will BE. Do antibioticimpregnated shunts in hydrocephalus therapy reduce the risk of infection? an observational study in 258 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 7:38. 2007.

Article25. Simon TD, Pope CE, Browd SR, Ojemann JG, Riva-Cambrin J, Mayer-Hamblett N, et al. Evaluation of microbial bacterial and fungal diversity in cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection. PLoS One. 9:e83229. 2014.

Article26. Theophilus SC, Adnan JS. A randomised control trial on the use of topical methicillin in reducing post-operative ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection. Malays J Med Sci. 18:30–37. 2011.27. Wang KW, Chang WN, Shih TY, Huang CR, Tsai NW, Chang CS, et al. Infection of cerebrospinal fluid shunts: causative pathogens, clinical features, and outcomes. Jpn J Infect Dis. 57:44–48. 2004.28. Wells DL, Allen JM. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt infections in adult patients. AACN Adv Crit Care. 24:6–12. quiz 13-14. 2013.

Article29. Zeeuwen PL, Boekhorst J, van den Bogaard EH, de Koning HD, van de Kerkhof PM, Saulnier DM, et al. Microbiome dynamics of human epidermis following skin barrier disruption. Genome Biol. 13:R101. 2012.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Two Cases of Allergic Contact Dermatitis due to Povidone-iodine

- Optimal Timing of Preoperative Skin Preparation with Povidone-Iodine for Spine Surgery: A Prospective, Randomized Controlled Study

- Primary Irritant Dermatitis to Povidone-Iodine after Caudal Anesthesia: A Case Report

- Morphologic study of the ototoxicity of povidone-iodine preparation to the guinea pig middle ear

- A Case of Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Antiseptics