Yonsei Med J.

2005 Dec;46(6):737-749.

Anatomic Basis of Sharp Pelvic Dissection for Curative Resection of Rectal Cancer

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Surgery, Division of Colorectal Surgery, Colorectal Cancer Special Clinic, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Abstract

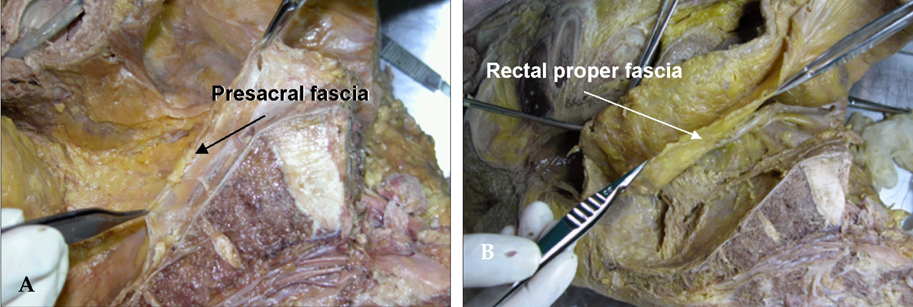

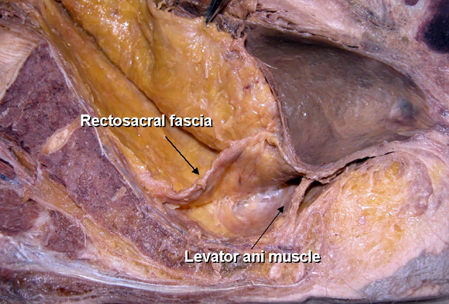

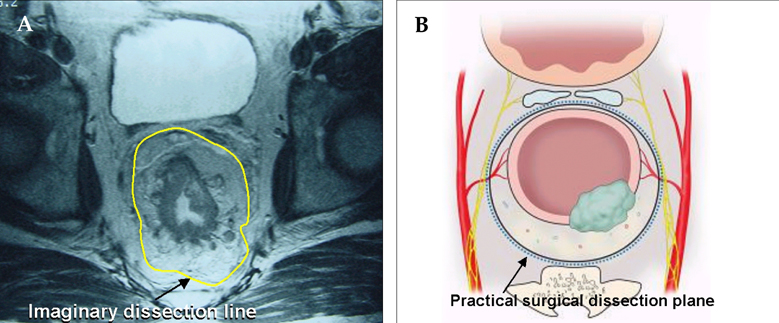

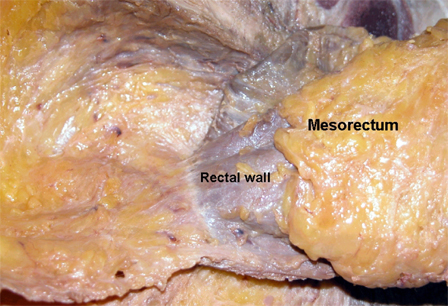

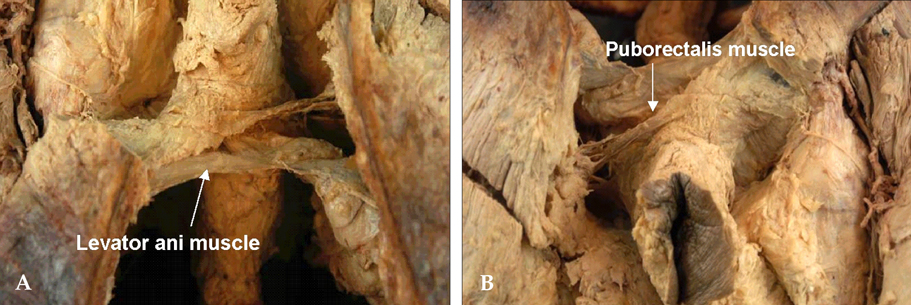

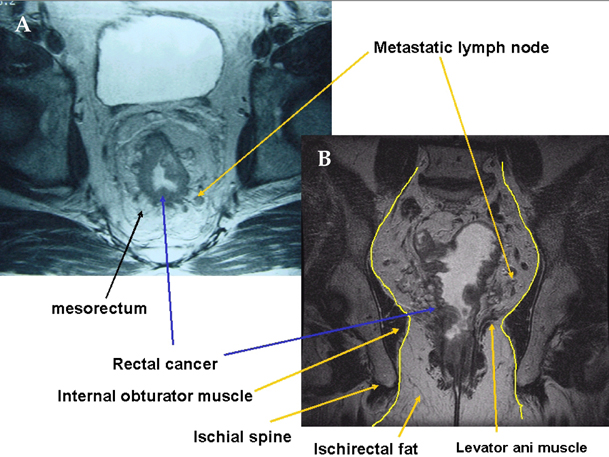

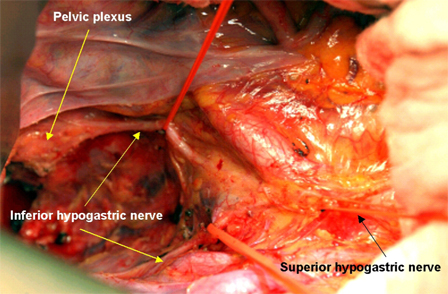

- The optimal goals in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer are curative resection, anal sphincter preservation, and preservation of sexual and voiding functions. The quality of complete resection of rectal cancer and the surrounding mesorectum can determine the prognosis of patients and their quality of life. With the emergence of total mesorectal excision in the field of rectal cancer surgery, anatomical sharp pelvic dissection has been emphasized to achieve these therapeutic goals. In the past, the rates of local recurrence and sexual/ voiding dysfunction have been high. However, with sharp pelvic dissection based on the pelvic anatomy, local recurrence has decreased to less than 10%, and the preservation rate of sexual and voiding function is high. Improved surgical techniques have created much interest in the surgical anatomy related to curative rectal cancer surgery, with particular focus on the fascial planes and nerve plexuses and their relationship to the surgical planes of dissection. A complete understanding of rectum anatomy and the adjacent pelvic organs are essential for colorectal surgeons who want optimal oncologic outcomes and safety in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA. 1990. 264:1444–1450.2. Maurer CA, Z'Graggen K, Renzulli P, Schilling MK, Netzer P, Buchler MW. Total mesorectal excision preserves male genital function compared with conventional rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2001. 88:1501–1505.3. Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery-the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982. 69:613–616.4. Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986. 1:1479–1482.5. MacFarlane JK, Ryall RD, Heald RJ. Mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1993. 341:457–460.6. Enker WE, Thaler HT, Cranor ML, Polyak T. Total mesorectal excision in the operative treatment of carcinoma of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1995. 181:335–346.7. Enker WE, Merchant N, Cohen AM, Lanouette NM, Swallow C, Guillem J, et al. Safety and efficacy of low anterior resection for rectal cancer: 681 consecutive cases from a specialty service. Ann Surg. 1999. 230:544–554.8. Sugihara K, Moriya Y, Akasu T, Fujita S. Pelvic autonomic nerve preservation for patients with rectal carcinoma. Oncologic and functional outcome. Cancer. 1996. 78:1871–1880.9. Kim NK, Aahn TW, Park JK, Lee KY, Lee WH, Sohn SK, et al. Assessment of sexual and voiding function after total mesorectal excision with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation in males with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002. 45:1178–1185.10. Quirke P, Durdey P, Dixon MF, Williams NS. Local recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma due to inadequate surgical resection. Histopathological study of lateral tumor spread and surgical excision. Lancet. 1986. 2:996–999.11. Adam IJ, Mohamdee MO, Martin IG, Scott N, Finan PJ, Johnston D, et al. Role of circumferential margin involvement in the local recurrence of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1994. 344:707–711.12. Takahashi T, Ueno M, Azekura K, Ohta H. Lateral node dissection and total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000. 43:S59–S68.13. Fujita S, Yamamoto S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Lateral pelvic lymph node dissection for advanced lower rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003. 90:1580–1585.14. Bisset IP, Chau KY, Hill GL. Extrafascial excision of the rectum: surgical anatomy of the fascia propria. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000. 43:903–910.15. Diop M, Parratte B, Tatu L, Vuillier F, Brunelle S, Monnier G. "Mesorectum": the surgical value of an anatomical approach. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003. 25:290–304.16. Kim NK. Anatomic basis of sharp pelvic dissection for total mesorectal excision with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation for rectal cancer. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2004. 20:424–433.17. Kim NK. Sharp pelvic dissection for abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancer based on anatomical and MRI knowledge. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2005. 21:258–267.18. Crapp AR, Cuthbertson AM. Willaim Waldeyer and the rectosacral fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974. 138:252–256.19. Tobin CE, Benjamin JA. Anatomical and surgical restudy of Denonvilliers' fascia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1945. 80:373–388.20. Milley PS, Nichols DH. A correlative investigation of the human rectovaginal septum. Anat Rec. 1969. 163:443–451.21. Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Brown G, Daniels IR. Optimal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer is by dissection in front of Denonvilliers' fascia. Br J Surg. 2004. 91:121–123.22. Mundy AR. An anatomical explanation for bladder dysfunction following rectal and uterine surgery. Br J Urol. 1982. 54:501–504.23. Hoer J, Roegels A, Prescher A, Klosterhalfen B, Tons C, Schumpelick V. Preserving autonomic nerves in rectal surgery. Results of surgical preparation on human cadavers with fixed pelvic sections. Chirurg. 2000. 71:1222–1229.24. Sato K, Sato T. The vascular and neuronal composition of the lateral ligament of the rectum and the rectosacral fascia. Surg Radiol Anat. 1991. 13:17–22.25. Yamakoshi H, Ike H, Oki S, Hara M, Shimada H. An assessment of the anatomical relationship between the pelvic plexus and the rectal wall to determine the indications for its preservation in surgery for rectal cancer. Surg Today. 1997. 27:1005–1009.26. Widmer O. Rectal arteries in man; entrance, caliber, distribution, anastomosis and supply area. Z Anat Entwicklungs-gesc. 1955. 118:398–416.27. DiDio LJ, Diaz-Franco C, Schemainda R, Bezerra A. Morphology of the middle rectal arteries: A study of 30 cadaveric dissections. Surg Radiol Anat. 1986. 8:229–236.28. Nano M, Dal Corso HM, Lanfranco G, Ferronato M, Hornung JP. Contribution to the surgical anatomy of the ligaments of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000. 43:1592–1598.29. Jones OM, Smeulders N, Wiseman O, Miller R. Lateral ligaments of the rectum: an anatomical study. Br J Surg. 1999. 86:487–489.30. Lee JF, Maurer VM, Block GE. Anatomic relations of pelvic autonomic nerves to pelvic operations. Arch Surg. 1973. 107:324–328.31. Kirkham AP, Mundy AR, Heald RJ, Scholefield JH. Cadaveric dissection for the rectal surgeon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001. 83:89–95.32. Walsh PC, Donker PJ. Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention. J Urol. 1982. 128:492–497.33. Havenga K, Maas CP, DeRuiter MC, Welvaart K, Trimbos JB. Avoiding long-term disturbance to bladder and and sexual function in pelvic surgery, particularly with rectal cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000. 18:235–243.34. Havenga K, DeRuiter MC, Enker WE, Welvaart K. Anatomical basis of autonomic nerve-preserving total mesorectal excision for rectal camcer. Br J Surg. 1996. 83:384–388.35. Walsh PC, Schlegel PN. Radical pelvic surgery with preservation of sexual function. Ann Surg. 1988. 208:391–400.36. Hollabaugh RS Jr, Steiner MS, Sellers KD, Samm BJ, Dmochowski RR. Neuroanatomy of the pelvis: implications for colonic and rectal resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000. 43:1390–1397.37. Church JM, Raudkivi PJ, Hill GL. The surgical anatomy of the rectum - a review with particular relevance to the hazards of rectal mobilization. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1987. 2:158–166.38. Marr R, Birbeck K, Garvican J, Macklin CP, Tiffin NJ, Parsons WJ, et al. The modern abdominoperineal excision: the next challenge after total mesorectal excision. Ann Surg. 2005. 242:74–82.39. Schiessel R, Novi G, Holzer B, Rosen HR, Renner K, Hoebling N, et al. Technique and long-term results of intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005. 48:1858–1867.40. Brown G, Kirkham A, Williams GT, Bourne M, Radcliffe AG, Sayman J, et al. High-resolution MRI of the anatomy important in total mesorectal excision of the rectum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004. 182:431–439.41. In : Kim NK, editor. 2005. Tumor specific mesorectal excision for rectal cancer workshop; Seoul. MEDrang Inc.: Clinical research center for solid tumor sponsored by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea;Contract No. 0412-CR01-0704-0001.42. Wibe A, Moller B, Norstein J, Carlsen E, Wiig JN, Heald RJ, et al. A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer-implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002. 45:857–866.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Anatomic Basis of Sharp Pelvic Dissection for Total Mesorectal Excision with Pelvic Autonomic Nerve Preservation for Rectal Cancer

- Effect on the Local Recurrence and the Survival of Total Mesorectal Excision and Lateral Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Rectal Cancer

- Clinical Implication of Lateral Pelvic Lymph Node Metastasis in Rectal Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy

- Rectal Cancer: Function-preserving Surgery

- Curative Groin Dissection of Inguinal Lymph Node Metastasis from Lower Rectal Cancer: The Operative Technique and a Report of Four Cases