J Korean Acad Nurs.

2016 Aug;46(4):610-617. 10.4040/jkan.2016.46.4.610.

Timely Interventions can Increase Smoking Cessation Rate in Men with Ischemic Stroke

- Affiliations

-

- 1Department of Neurology, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 2Division of Nursing, Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea. hsnam@yuhs.ac

- 3Department of Cardiovascular Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 4Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- 5Biostatistics Collaboration Unit, (Department of Research Affairs) Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

- KMID: 2424557

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2016.46.4.610

Abstract

- PURPOSE

Smoking cessation is strongly recommended for every smoker after ischemic stroke, but many patients fail to quit smoking. An improved smoking cessation rate has been reported with intensive behavioral therapy during hospitalization and supportive contact after discharge. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the usefulness of the timely interventions for smoking cessation in men with acute ischemic stroke.

METHODS

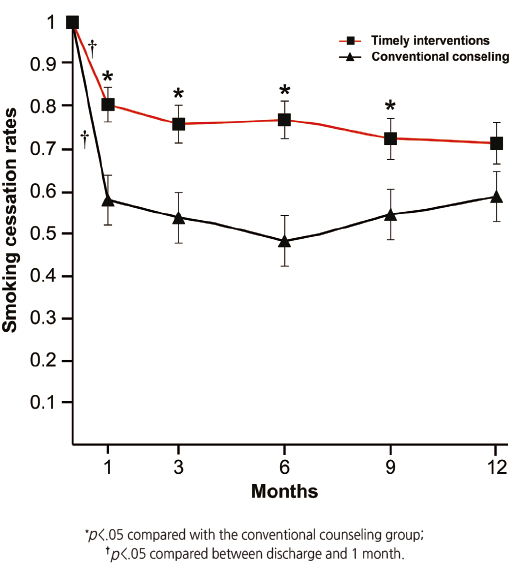

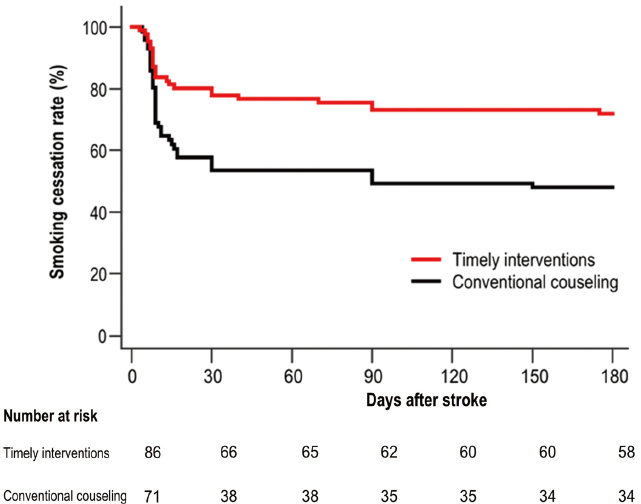

Patients who participated in the timely interventions strategy (TI group) were compared with those who received conventional counseling (CC group). In the TI group, a certified nurse provided comprehensive education during admission and additional counseling after discharge. Outcome was measured by point smoking success rate and sustained smoking cessation rate for 12 months.

RESULTS

Participants, 157 men (86 of the TI group and 71 of the CC group), were enrolled. Mean age was 58.25 ± 11.23 years and mean initial National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 4.68 ± 5.46. The TI group showed a higher point smoking success rate compared with the CC group (p= .003). Multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the TI group was 2.96-fold (95% CI, 1.43~6.13) more likely to sustain smoking cessation for 12 months than the CC group.

CONCLUSION

Findings indicate that multiple interventions initiated during hospital stay and regular follow-up after discharge are more effective than conventional smoking cessation counseling in men with acute ischemic stroke.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Lee JH, Lee JY, Ahn SH, Jang MU, Oh MS, Kim CH, et al. Smoking is not a good prognostic factor following first-ever acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke. 2015; 17(2):177–191. DOI: 10.5853/jos.2015.17.2.177.2. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, Albers GW, Bush RL, Fagan SC, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011; 42(1):227–276. DOI: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043.3. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (2):CD001292. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.cd001292.4. Stead LF, Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; (2):CD001007. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub2.5. Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (3):CD002850.6. Kim H, Kim O. The lifestyle modification coaching program for secondary stroke prevention. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2013; 43(3):331–340. DOI: 10.4040/jkan.2013.43.3.331.7. Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; (2):CD000165. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub3.8. Sauerbeck LR, Khoury JC, Woo D, Kissela BM, Moomaw CJ, Broderick JP. Smoking cessation after stroke: Education and its effect on behavior. J Neurosci Nurs. 2005; 37(6):316–319. 3259. Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, Alberts MJ, Benavente O, Furie K, et al. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: Co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Stroke. 2006; 37(2):577–617. DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.4.853.10. Oh SM, Stefani KM, Kim HC. Development and application of chronic disease risk prediction models. Yonsei Med J. 2014; 55(4):853–860. DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.4.853.11. Stringhini S, Spencer B, Marques-Vidal P, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Paccaud F, et al. Age and gender differences in the social patterning of cardiovascular risk factors in Switzerland: The CoLaus study. PLoS One. 2012; 7(11):e49443. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049443.12. Lee BI, Nam HS, Heo JH, Kim DI. Yonsei stroke registry. Analysis of 1,000 patients with acute cerebral infarctions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001; 12(3):145–151. DOI: 10.1159/000047697.13. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45(7):2160–2236. DOI: 10.1161/str.0000000000000024.14. Ives SP, Heuschmann PU, Wolfe CD, Redfern J. Patterns of smoking cessation in the first 3 years after stroke: The South London stroke register. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008; 15(3):329–335. DOI: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f37a58.15. Bruce N, Pope D, Stanistreet D. Quantitative methods for health research: a practical interactive guide to epidemiology and statistics. Wiley;2013. p. 293.16. Redfern J, McKevitt C, Dundas R, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. Behavioral risk factor prevalence and lifestyle change after stroke: A prospective study. Stroke. 2000; 31(8):1877–1881. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.31.8.1877.17. Bak S, Sindrup SH, Alslev T, Kristensen O, Christensen K, Gaist D. Cessation of smoking after first-ever stroke: A follow-up study. Stroke. 2002; 33(9):2263–2269. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.0000027210.50936.D0.18. Sappok T, Faulstich A, Stuckert E, Kruck H, Marx P, Koennecke HC. Compliance with secondary prevention of ischemic stroke: A prospective evaluation. Stroke. 2001; 32(8):1884–1889. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.32.8.1884.19. Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; (3):CD001837. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub2.20. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz N, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Quick reference guide for clinicians [Internet]. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services;2008. cited 2016 January 1. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelinesrecommendations/tobacco/clinicians/references/quickref/index.html.21. Ovbiagele B, Kidwell CS, Selco S, Razinia T, Saver JL. Treatment adherence rates one year after initiation of a systematic hospital-based stroke prevention program. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005; 20(4):280–282. DOI: 10.1159/000087711.22. McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: The case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003; 18(2):156–170.23. France EK, Glasgow RE, Marcus AC. Smoking cessation interventions among hospitalized patients: What have we learned? Prev Med. 2001; 32(4):376–388. DOI: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0824.24. Rice VH, Stead LF. Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; (1):CD001188. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001188.pub3.25. Schuck K, Otten R, Kleinjan M, Bricker JB, Engels RC. Effectiveness of proactive telephone counselling for smoking cessation in parents: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2011; 11:732. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-732.26. Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: Factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav. 2009; 34(4):365–373. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013.27. McRobbie H, Hajek P. Nicotine replacement therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease: Guidelines for health professionals. Addiction. 2001; 96(11):1547–1551. DOI: 10.1080/09652140120080688.

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Factors Influencing Smoking Cessation Behavior in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease Following Coronary Angiography

- Factors Affecting Smoking Cessation Success during 4-week Smoking Cessation Program for University Students

- A Survey on Frequencies of Smoking Cessation Intervention for Patients Among Clinical Nurses

- Gender Differences in Risk Factor and Clinical Outcome in Patients with Ischemic Stroke

- Attitudes to Smoking Cessation Interventions and Importance of Participation in Tobacco Control Policy Among Clinical Nurses