Korean J Orthod.

2018 May;48(3):182-188. 10.4041/kjod.2018.48.3.182.

Use of autonomous maximal smile to evaluate dental and gingival exposure

- Affiliations

-

- 1State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Orthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China. yuli@scu.edu.cn

- 2Discipline of Orthodontics, Department of Oral Sciences, Sir John Walsh Research Institute, Faculty of Dentistry, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

- 3State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of maxillofacial surgery, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China.

- KMID: 2418329

- DOI: http://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2018.48.3.182

Abstract

OBJECTIVE

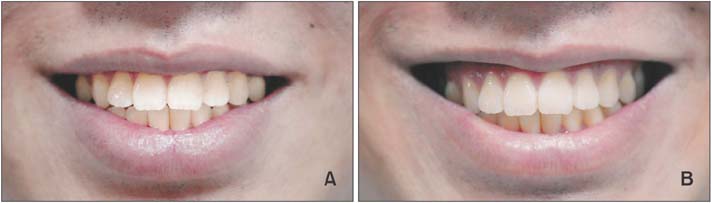

This study was performed to validate the autonomous maximal smile (AMS) as a new reference for evaluating dental and gingival exposure.

METHODS

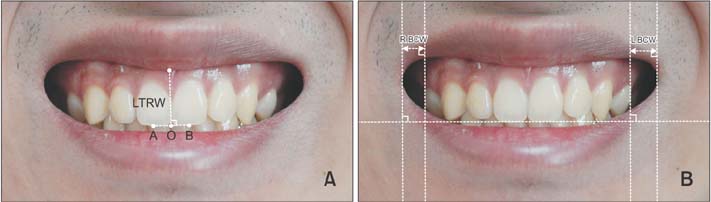

Digital video clips of 100 volunteers showing posed smiles and AMS at different verbal directives were recorded for evaluation a total of three times at 1-week intervals. Lip-teeth relationship width (LTRW) and buccal corridor width (BCW) were measured. LTRW represented the vertical distance between the inferior border of the upper vermilion and the edge of the maxillary central incisors. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for reproducibility, and the m-value (minimum number of repeated measurements required for an ICC level over 0.75), were calculated.

RESULTS

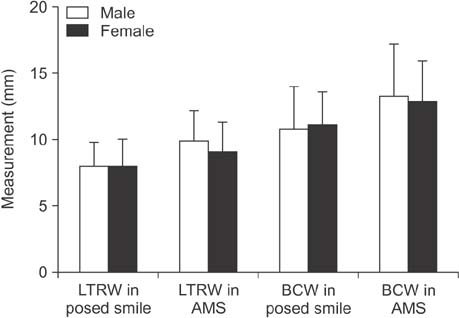

LTRW and BCW of the AMS were 1.41 and 2.04 mm, respectively, greater than those of the posed smile (p < 0.05), indicating significantly larger dental and gingival exposure in the AMS. The reproducibility of the AMS (0.74 to 0.77) was excellent, and higher than that of the posed smile (0.62 to 0.65), which had fair-to-good reproducibility. Moreover, the m-value of the AMS (0.88 to 1.05) was lower than that of the posed smile (1.59 to 1.85).

CONCLUSIONS

Compared to the posed smile, the AMS shows significantly larger LTRW and BCW, with significantly higher reproducibility. The AMS might serve as an adjunctive reference, in addition to the posed smile, in orthodontic and other dentomaxillofacial treatments.

Keyword

MeSH Terms

Figure

Reference

-

1. Shaw WC, Rees G, Dawe M, Charles CR. The influence of dentofacial appearance on the social attractiveness of young adults. Am J Orthod. 1985; 87:21–26.

Article2. Valstar MF, Gunes H, Pantic M. How to distinguish posed from spontaneous smiles using geometric features. In : Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Multimodal Interfaces; 2007.3. van der Geld PA, Oosterveld P, van Waas MA, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Digital videographic measurement of tooth display and lip position in smiling and speech: reliability and clinical application. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007; 131:301.e1–301.e8.

Article4. Tarantili VV, Halazonetis DJ, Spyropoulos MN. The spontaneous smile in dynamic motion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005; 128:8–15.

Article5. Mishima K, Umeda H, Nakano A, Shiraishi R, Hori S, Ueyama Y. Three-dimensional intra-rater and interrater reliability during a posed smile using a video-based motion analyzing system. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2014; 42:428–431.

Article6. Havens DC, McNamara JA Jr, Sigler LM, Baccetti T. The role of the posed smile in overall facial esthetics. Angle Orthod. 2010; 80:322–328.

Article7. Krishnan V, Daniel ST, Lazar D, Asok A. Characterization of posed smile by using visual analog scale, smile arc, buccal corridor measures, and modified smile index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; 133:515–523.

Article8. Sarver DM. The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001; 120:98–111.

Article9. Jack RE, Blais C, Scheepers C, Schyns PG, Caldara R. Cultural confusions show that facial expressions are not universal. Curr Biol. 2009; 19:1543–1548.

Article10. Yuki M, Maddux WW, Masuda T. Are the windows to the soul the same in the East and West? Cultural differences in using the eyes and mouth as cues to recognize emotions in Japan and the United States. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007; 43:303–311.

Article11. Walder JF, Freeman K, Lipp MJ, Nicolay OF, Cisneros GJ. Photographic and videographic assessment of the smile: objective and subjective evaluations of posed and spontaneous smiles. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013; 144:793–801.

Article12. Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod. 2002; 36:221–236.13. Schabel BJ, Baccetti T, Franchi L, McNamara JA. Clinical photography vs digital video clips for the assessment of smile esthetics. Angle Orthod. 2010; 80:490–496.

Article14. Landers RN. Computing intraclass correlations (ICC) as estimates of interrater reliability in SPSS [Internet]. NeoAcademic;2011. 11. 16. cited 2016 Jul 30. Available from: http://neoacademic.com/2011/11/16/computing-intraclass-correlationsicc-as-estimates-of-interrater-reliability-in-spss/.15. Rosner B. Fundamentals of biostatistics. 5th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Thomson Learning;2000. p. 563.16. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979; 86:420–428.

Article17. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977; 33:159–174.

Article18. Ackerman JL, Ackerman MB, Brensinger CM, Landis JR. A morphometric analysis of the posed smile. Clin Orthod Res. 1998; 1:2–11.

Article19. Hwang WS, Hur MS, Hu KS, Song WC, Koh KS, Baik HS, et al. Surface anatomy of the lip elevator muscles for the treatment of gummy smile using botulinum toxin. Angle Orthod. 2009; 79:70–77.

Article20. Peck S, Peck L. Selected aspects of the art and science of facial esthetics. Semin Orthod. 1995; 1:105–126.

Article21. Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. The gingival smile line. Angle Orthod. 1992; 62:91–100.22. Johnston DJ, Millett DT, Ayoub AF, Bock M. Are facial expressions reproducible? Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2003; 40:291–296.

Article23. Sforza C, Mapelli A, Galante D, Moriconi S, Ibba TM, Ferraro L, et al. The effect of age and sex on facial mimicry: a three-dimensional study in healthy adults. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 39:990–999.

Article24. Ioi H, Nakata S, Counts AL. Effects of buccal corridors on smile esthetics in Japanese. Angle Orthod. 2009; 79:628–633.

Article25. Roden-Johnson D, Gallerano R, English J. The effects of buccal corridor spaces and arch form on smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005; 127:343–350.

Article26. Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Schols J, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Smile line assessment comparing quantitative measurement and visual estimation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:174–180.

Article

- Full Text Links

- Actions

-

Cited

- CITED

-

- Close

- Share

- Similar articles

-

- Treatment of Gingival Smile by Botulinum Toxin A

- Treatment of gummy smile using botulinum toxin: a review

- Microsurgical Approach for Root Coverage of Receding Gingiva in the Esthetic Zone

- Orthodontic treatment of gummy smile by maxillary total intrusion with a midpalatal absolute anchorage system

- Perception of discrepancy in the upper midline position in conjunction with the gingival display according to various occupations in Iran